Rosso Fiorentino and Pontormo (Florence, 4 Apr 14)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

The Exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

Issue no. 18 - April 2014 CHAMPIONS OF THE “MODERN MANNER” The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism”, points out the different vocations of the two great artist of the Cinquecento, both trained under Andrea del Sarto. Palazzo Strozzi will be hosting from March 8 to July 20, 2014 a major exhibition entitled Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism. The exhibit is devoted to these two painters, the most original and unconventional adepts of the innovative interpretive motif in the season of the Italian Cinquecento named “modern manner” by Vasari. Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino both were born in 1494; Pontormo in Florence and Rosso in nearby Empoli, Tuscany. They trained under Andrea del Sarto. Despite their similarities, the two artists, as the title of the exhibition suggests, exhibited strongly independent artistic approaches. They were “twins”, but hardly identical. An abridgement of the article “I campioni della “maniera moderna” by Antonio Natali - Il Giornale degli Uffizi no. 59, April 2014. Issue no. 18 -April 2014 PONTORMO ACCORDING TO BILL VIOLA The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi includes American artist Bill Viola’s video installation “The Greeting”, a intensely poetic interpretation of The Visitation by Jacopo Carrucci Through video art and the technique of slow motion, Bill Viola’s richly poetic vision of Pontormo’s painting “Visitazione” brings to the fore the happiness of the two women at their coming together, representing with the same—yet different—poetic sensitivity, the vibrancy achieved by Pontormo, but with a vital, so to speak carnal immediacy of the sense of life, “translated” into the here-and- now of the present. -

He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ

9/22/2018 He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY DJIA 26743.50 0.32% ▲ S&P 500 2929.67 -0.04% ▼ Nasdaq 7986.96 -0.51% ▼ U.S. 10 Yr 032 Yield 3.064% ▼ Crude Oil 70.71 0.55% ▲ This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hewasmorethanamannerist1537614000 ART REVIEW He Was More Than a Mannerist Two Jacopo Pontormo masterpieces at the Morgan Library & Museum provide an opportunity to reassess his work. Pontormo’s ‘Visitation’ (c. 152829) PHOTO: CARMIGNANO, PIEVE DI SAN MICHELE ARCANGELO By Cammy Brothers Sept. 22, 2018 700 a.m. ET New York Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), one of the most accomplished and intriguing painters Florence ever produced, has been maligned by history on at least two fronts. First, by the great artist biographer Giorgio Vasari, who recognized Pontormo’s gifts but depicted him as a solitary eccentric who imitated the manner of the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer to a fault. And second, by art historians quick to label him as a “Mannerist,” a term that has often carried negative associations, broadly used to mean excessive artifice and often associated with a period of decline. The term isn’t wrong for Pontormo, but it’s a dead end, explaining away Pontormo’s distinctiveness while sidelining him at the same time. It’s not hard to understand how Pontormo got his Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters reputation. -

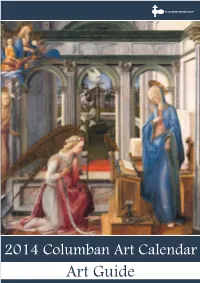

2014 Art Guide

2014 Columban Art Calendar Art Guide Front Cover The Annunciation, Verkuendigung Mariae (detail) Lippi, Fra Filippo (c.1406-1469) In Florence during the late middle ages and Renaissance the story of the Annunciation took on a special meaning. Citizens of this wealthy and pious city dated the beginning of the New Year at the feast day of the Annunciation, March 25th. In this city as elsewhere in Europe, where the cathedral was dedicated to her, the Virgin naturally held a special place in religious life. To emphasize this, Fra Filippo sets the moment of Gabriel’s visit to Mary in stately yet graceful surrounds which recede into unfathomable depths. Unlike Gabriel or Mary, the viewer can detect in the upper left-hand corner the figure of God the Father, who has just released the dove of the Holy Spirit. The dove, a traditional symbol of the third person of the Trinity, descends towards Mary in order to affirm the Trinitarian character of the Incarnation. The angel kneels reverently to deliver astounding news, which Mary accepts with surprising equanimity. Her eyes focus not on her angelic visitor, but rather on the open book before her. Although Luke’s gospel does not describe Mary reading, this detail, derived from apocryphal writings, hints at a profound understanding of Mary’s role in salvation history. Historically Mary almost certainly would not have known how to read. Moreover books like the one we see in Fra Filippo’s painting came into use only in the first centuries CE. Might the artist and the original owner of this painting have greeted the Virgin’s demeanour as a model of complete openness to God’s invitation? The capacity to respond with such inner freedom demanded of Mary and us what Saint Benedict calls “a listening heart”. -

Sight and Touch in the Noli Me Tangere

Chapter 1 Sight and Touch in the Noli me tangere Andrea del Sarto painted his Noli me tangere (Fig. 1) at the age of twenty-four.1 He was young, ambitious, and grappling for the first time with the demands of producing an altarpiece. He had his reputation to consider. He had the spiri- tual function of his picture to think about. And he had his patron’s wishes to address. I begin this chapter by discussing this last category of concern, the complex realities of artistic patronage, as a means of emphasizing the broad- er arguments of my book: the altarpiece commissions that Andrea received were learning opportunities, and his artistic decisions serve as indices of the religious knowledge he acquired in the course of completing his professional endeavors. Throughout this particular endeavor—from his first client consultation to the moment he delivered the Noli me tangere to the Augustinian convent lo- cated just outside the San Gallo gate of Florence—Andrea worked closely with other members of his community. We are able to identify those individuals only in a general sense. Andrea received his commission from the Morelli fam- ily, silk merchants who lived in the Santa Croce quarter of the city and who frequently served in the civic government. They owned the rights to one of the most prestigious chapels in the San Gallo church. It was located close to the chancel, second to the left of the apse.2 This was prime real estate. Renaissance churches were communal structures—always visible, frequently visited. They had a natural hierarchy, dominated by the high altar. -

The Strange Art of 16Th –Century Italy

The Strange Art of 16th –century Italy Some thoughts before we start. This course is going to use a seminar format. Each of you will be responsible for an artist. You will be giving reports on- site as we progress, in as close to chronological order as logistics permit. At the end of the course each of you will do a Power Point presentation which will cover the works you treated on-site by fitting them into the rest of the artist’s oeuvre and the historical context.. The readings: You will take home a Frederick Hartt textbook, History of Italian Renaissance Art. For the first part of the course this will be your main background source. For sculpture you will have photocopies of some chapters from Roberta Olsen’s book on Italian Renaissance sculpture. I had you buy Walter Friedlaender’s Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting, first published in 1925. While recent scholarship does not agree with his whole thesis, many of his observations are still valid about the main changes at the beginning and the end of the 16th century. In addition there will be some articles copied from art history periodicals and a few provided in digital format which you can read on the computer. Each of you will be doing other reading on your individual artists. A major goal of the course will be to see how sixteenth-century art depends on Raphael and Michelangelo, and to a lesser extent on Leonardo. Art seems to develop in cycles. What happens after a moment of great innovations? Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, seems to ask “where do we go from here?” If Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo were perfect, how does one carry on? The same thing occurred after Giotto and Duccio in the early Trecento. -

The Epistemology of the ABC Method Learning to Draw in Early Modern Italy

The Epistemology of the ABC Method Learning to Draw in Early Modern Italy Nino Nanobashvili Even if some northern European drawing books in the tradition of Albrecht Durer started with a dot, a line and geometrical figures (» Fig. 1), the so-called ABC meth- od was the most popular approach in the European manuals between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thus, these drawing books began by initially presenting the parts of the body in the same order: eyes, noses, mouth, ears, heads, hands, feet and so on, and continued by constructing the whole body. This method was named “ABC“ because of its basic character and because of parallelizing the drawing process of face members with letters.1 Most manuals for beginners from other fields were similarly named in general ABCs.2 Artists had been using the ABC method in their workshops at least since the mid-fifteenth century in Italy, much before the first drawing books were printed. Around 1600 it became so self-evident that a pupil should begin their drawing education with this method that one can recognize the youngest apprentices in programmatic images just by studying eyes and noses.3 Even on the ceiling of Sala del Disegno in the Roman Palazzo Zuccari the youngest student at the left of Pittura presents a piece of paper with a drafted eye, ear and mouth (» Fig. 2).4 What is the reason that the ABC method became so common at least in these three centuries? How could drawing body parts be useful at the beginning of artistic 1 In 1683, Giuseppe Mitelli arranged body parts together with letters in his drawing book Il Alfabeto del Sogno to emphasize this parallel. -

The Renaissance Workshop in Action

The Renaissance Workshop in Action Andrea del Sarto (Italian, 1486–1530) ran the most successful and productive workshop in Florence in the 1510s and 1520s. Moving beyond the graceful harmony and elegance of elders and peers such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Fra Bartolommeo, he brought unprecedented naturalism and immediacy to his art through the rough and rustic use of red chalk. This exhibition looks behind the scenes and examines the artist’s entire creative process. The latest technology allows us to see beneath the surface of his paintings in order to appreciate the workshop activity involved. The exhibition also demonstrates studio tricks such as the reuse of drawings and motifs, while highlighting Andrea’s constant dazzling inventiveness. All works in the exhibition are by Andrea del Sarto. This exhibition has been co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Frick Collection, New York, in association with the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. We acknowledge the generous support provided by an anonymous donation in memory of Melvin R. Seiden and by the Italian Cultural Institute. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2014 J. Paul Getty Trust Rendering Reality In this room we focus on Andrea’s much-lauded naturalism and how his powerful drawn studies enabled him to transform everyday people into saints and Madonnas, and smirking children into angels. With the example of The Madonna of the Steps, we see his constant return to life drawing on paper—even after he had started painting—to ensure truth to nature. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2014 J. -

78 – Entombment of Christ Jacobo Da Pontormo. 1525-28 C.E. Oil on Wood

78 – Entombment of Christ Jacobo da Pontormo. 1525-28 C.E. Oil on wood Video at Khan Academy Altarpiece (Renaissance) The Deposition is located above the altar of the Capponi Chapel of the church of Santa Felicita in Florence. Artist’s masterpiece This painting suggests a whirling dance of the grief-stricken flattened space what are we looking at? o No Cross is visible o the natural world itself also appears to have nearly vanished: a lonely cloud and a shadowed patch of ground with a crumpled sheet provide sky and stratum for the mourners o If the sky and earth have lost color, the mourners have not; bright swathes of pink and blue envelop the pallid, limp Christ (new) style: called Mannerist – o By the end of the High Renaissance, young artists experienced a crisis:[2] it seemed that everything that could be achieved was already achieved. No more difficulties, technical or otherwise, remained to be solved. The detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, physiognomy and the way in which humans register emotion in expression and gesture, the innovative use of the human form in figurative composition, the use of the subtle gradation of tone, all had reached near perfection. The young artists needed to find a new goal, and they sought new approaches.[citation needed] At this point Mannerism started to emerge.[2] The new style developed between 1510 and 1520 either in Florence,[14] or in Rome, or in both cities simultaneously o The word mannerism derives from the Italian maniera, meaning "style" or "manner" o Role model: Laocoon o Started -

Exploring the Path of Del Sarto, Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino Thursday, June 11Th Through Monday, June 15Th

- SUMMER 2015 FLORENCE PROGRAM Michelangelo and His Revolutionary Legacy: Exploring the Path of Del Sarto, Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino Thursday, June 11th through Monday, June 15th PRELIMINARY ITINERARY (as of January 2015) Program Costs: Program Fee: $4,000 per person (not tax deductible) Charitable Contribution: $2,500 per person (100% tax deductible) Historians: William Wallace, Ph.D. - Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History, Washington University in St. Louis William Cook, Ph.D. - Distinguished Teaching Professor of History, SUNY Geneseo (Emeritus) For additional program and cost details, please see the "Reservation Form," "Terms and Conditions," and "Hotel Lungarno Reservation Form" Thursday, June 11th Afternoon Welcome Lecture by historians Bill Wallace and Bill Cook, followed by private visits to the Medici Chapels. Dinner in an historic landmark of the city. Friday, June 12th Special visit to the church of Santa Felicità to view the extraordinary Pontormo masterpieces, then follow the path across Florence of a selection of frescoes from the Last Supper cycle. The morning will end with a viewing of the Last Supper by Andrea del Sarto in San Salvi. Lunch will be enjoyed on the hillsides of Florence. Later-afternoon private visit to the Bargello Museum, followed by cocktails and dinner in a private palace. Saturday, June 13th Morning departure via fast train to Rome. View Michelangelo's Moses and Risen Christ, followed by lunch. Private visit to the magnificent Palazzo Colonna to view their collection of works by Pontormo, Ridolfo da Ghirlandaio, and other artists. Later afternoon private visit to the Vatican to view the unique masterpieces by Michelangelo in both the Pauline Chapel and the Sistine Chapel, kindly arranged by the Papal offices and the Director of the Vatican Museums. -

Giorgio Vasari at 500: an Homage

Giorgio Vasari at 500: An Homage Liana De Girolami Cheney iorgio Vasari (1511-74), Tuscan painter, architect, art collector and writer, is best known for his Le Vile de' piu eccellenti architetti, Gpittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives if the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors if Italy, from Cimabue to the present time).! This first volume published in 1550 was followed in 1568 by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists' portraits. 2 By virtue of this text, Vasari is known as "the first art historian" (Rud 1 and 11)3 since the time of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historiae (Natural History, c. 79). It is almost impossible to imagine the history ofItalian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Lives. It is the first real and autonomous history of art both because of its monumental scope and because of the integration of the individual biographies into a whole. According to his own account, Vasari, as a young man, was an apprentice to Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, and Baccio Bandinelli in Florence. Vasari's career is well documented, the fullest source of information being the autobiography or vita added to the 1568 edition of his Lives (Vasari, Vite, ed. Bettarini and Barocchi 369-413).4 Vasari had an extremely active artistic career, but much of his time was spent as an impresario devising decorations for courtly festivals and similar ephemera. He praised the Medici family for promoting his career from childhood, and much of his work was done for Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany. -

The Trend Towards the Restitution of Cultural Properties: Some Italian Cases

CHAPTER twenty-three THE TREND TOWARDS THE RESTITUTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES: SOME ITALIAN CASES Tullio Scovazzi* 1. The Basic Aspects of the Italian Legislation The importance of cultural heritage is rooted in the mind of the majority of Ital- ians. The unification of the country was first achieved in the cultural field, due to the Divina Commedia of Dante (1265–1321) and the literary works of Petrarch and Boccaccio (XIV century), written in the Italian language and not in Latin. The cultural dimension was strengthened by the great artistic tradition of the Renaissance and the Baroque styles which originated in Italy. The political uni- fication of the country followed much later, as the kingdom of Italy was pro- claimed only in 1861. One of the first instances of legislation in the field of cultural properties is a decision taken in 1602 by the grand duke of Tuscany, subjecting to a licence the export from the State of “good paintings” and prohibiting altogether the export of the works of nineteen selected masters, namely Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raf- faello Sanzio, Andrea del Sarto, Mecherino, Rosso Fiorentino, Leonardo da Vinci, Franciabigio, Pierin del Vaga, Jacopo da Pontormo, Tiziano, Francesco Salviati, Bronzino, Daniele da Volterra, Fra Bartolomeo, Sebastiano del Piombo, Filippino Lippi, Correggio, Parmigianino and Perugino.1 The legislation adopted in the Papal State at the beginning of the XIX century, in particular the edicts enacted respectively on 2 October 1802 and on 7 April 1820, set forth a number of fundamental principles that are reflected also in the legislation in force today. Private subjects have to declare to the State the cul- tural properties of which they were owners.