Taking and Killing of Hostages: Coercion and Reprisal in International Law Mary Kay Mattson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Belligerent Reprisals in the Age of Cyber?

Marquette Law Review Volume 102 Article 5 Issue 1 Fall 2018 Revisiting Belligerent Reprisals in the Age of Cyber? Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Repository Citation Revisiting Belligerent Reprisals in the Age of Cyber?, 102 Marq. L. Rev. 81 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol102/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized editor of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVISITING BELLIGERENT REPRISALS IN THE AGE OF CYBER? DAVID WALLACE,SHANE REEVES &TRENT POWELL* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 81 II. THE HISTORY OF BELLIGERENT REPRISALS IN IHL ................................... 85 III. BELLIGERENT REPRISALS TODAY IN IHL ................................................. 91 IV. CYBER OPERATIONS AND BELLIGERENT REPRISALS: THE LEX LATA ....... 94 V. COUNTERMEASURES UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW .................................. 96 VI. BELLIGERENT REPRISALS AND CYBER:ATHEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 104 VII. CONCLUSION......................................................................................... -

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-366 November 2003 Articles Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials: A Rebuttal to Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Colonel Frederic L. Borch, III Editorial Comment: A Response to Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Afghanistan, Quirin, and Uchiyama: Does the Sauce Suit the Gander Evan J. Wallach Note from the Field Legal Cultures Clash in Iraq Lieutenant Colonel Craig T. Trebilcock The Art of Trial Advocacy Preparing the Mind, Body, and Voice Lieutenant Colonel David H. Robertson, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center & School, U.S. Army CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor’s Note An article in our April/May 2003 Criminal Law Symposium issue, Moving Toward the Apex: New Developments in Military Jurisdiction, discussed the recent ACCA and CAAF opinions in United States v. Sergeant Keith Brevard. These opinions deferred to findings the trial court made by a preponderance of the evidence to resolve a motion to dismiss, specifically that the accused obtained and presented forged documents to procure a fraudulent discharge. Since the publication of these opinions, the court-matial reached the ultimate issue of the guilt of the accused on remand. The court-martial acquitted the accused of fraudulent separation and dismissed the other charges for lack of jurisdiction. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

Three Theories of Just War: Understanding Warfare As a Social Tool Through Comparative Analysis of Western, Chinese, and Islamic Classical Theories of War

THREE THEORIES OF JUST WAR: UNDERSTANDING WARFARE AS A SOCIAL TOOL THROUGH COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF WESTERN, CHINESE, AND ISLAMIC CLASSICAL THEORIES OF WAR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHY MAY 2012 By Faruk Rahmanović Thesis Committee: Tamara Albertini, Chairperson Roger T. Ames James D. Frankel Brien Hallett Keywords: War, Just War, Augustine, Sunzi, Sun Bin, Jihad, Qur’an DEDICATION To my parents, Ahmet and Nidžara Rahmanović. To my wife, Majda, who continues to put up with me. To Professor Keith W. Krasemann, for teaching me to ask the right questions. And to Professor Martin J. Tracey, for his tireless commitment to my success. 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this analysis was to discover the extent to which dictates of war theory ideals can be considered universal, by comparing the Western (European), Classical Chinese, and Islamic models. It also examined the contextual elements that drove war theory development within each civilization, and the impact of such elements on the differences arising in war theory comparison. These theories were chosen for their differences in major contextual elements, in order to limit the impact of contextual similarities on the war theories. The results revealed a great degree of similarities in the conception of warfare as a social tool of the state, utilized as a sometimes necessary, albeit tragic, means of establishing peace justice and harmony. What differences did arise, were relatively minor, and came primarily from the differing conceptions of morality and justice within each civilization – thus indicating a great degree of universality to the conception of warfare. -

High Command Case: a Study in Staff and Command Responsibility

JOHN JAY DOUGLASS* Colonel, JAGC High Command Case: A Study in Staff and Command Responsibility Less than twenty-five years after the conclusion of the major World War I1war crimes trials, international jurists, historians and the general public are not clear as to, nor are they apparently concerned with, the authority, procedure or even the significant legal decisions of the war crimes trials held both in Europe and the Far East following World War 11.1 Even a mere twenty-five years of experience indicates there will be other trials of those accused of criminal acts in war. Such trials, as well as international lawmakers, should well review the German High Command Trial before the United States Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1948. The lessons of this trial may well be the most important of those from any of the trials held following World War 11. The thrust of this trial and its results relate to the authority of command- ers of military forces for actions of their troops and their personal respon- sibility, as well as the responsibility of staff officers in senior staff positions, for'actions taken by them or carried on under their direction. As a result of recent developments within the United States, arising from the war in Vietnam, it is worthwhile to review the German High Command Trial and to analyze its relationship to the present state of the law. The legal question of criminal responsibility of military commanders and staff officers who do *Commandant (Dean), The Judge Advocate General's School, U.S. -

Brian Orend–Just and Lawful Conduct in War- Reflections on Michael

!"#$%&'(%)&*+",%-.'("/$%0'%1&23%45+,5/$0.'#%.'%60/7&5,%1&,852 9"$7.2:#;3%<20&'%=25'( >."2/53%)&*%&'(%?70,.#.@7AB%C.,D%EFB%G.D%H%:!&'DB%EFFH;B%@@D%HIJF ?"K,0#75(%KA3%Springer >$&K,5%L4)3%http://www.jstor.org/stable/3505049 . 9//5##5(3%EMNFHNEFHH%HH3HM Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Law and Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org BRIAN OREND JUST AND LAWFULCONDUCT IN WAR:REFLECTIONS ON MICHAELWALZ7ER -

FACULTY of LAW 2014/2015 the Critical Analysis on the 'Belligerent

0 FACULTY OF LAW 2014/2015 The Critical Analysis on the ‘Belligerent Reprisals’ as Means ofSubject Enforcement: Thesis (Final of) DraftInternational Humanitarian Law: Inconsistency between International Humanitarian Law and International Criminal Law and Legitimacy Issues A thesis submitted in a partial fulfillment of academic requirements for the award of a Master Degree in International and European Law and the Title of Master of Laws (LLM) By, Protogène DUSABE Supervisor: Prof H.G. van der Wilt Amsterdam, 26 June 2015 i DECLARATION I, DUSABE Protogène, here-by declare that, this research work entitled “The Critical Analysis on the ‘Belligerent Reprisals’ as Means of Enforcement of International Humanitarian Law: Inconsistency between International Humanitarian Law and International Criminal Law and Legitimacy Issues” is to the best of my knowledge and belief original, apart from where acknowledged in the text, and has not previously been submitted in any institution for the award of a Degree or Diploma. DUSABE Protogène June 2015 ii DEDICATION To The Almighty God; To our spouse Kayitesi M. Assumpta; To our daughters Glenda and Ingrid; To our deceased father; To our much-loved mother; To all those who advocate the cause of humanity iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an achievement that leaves me highly indebted to The Almighty God for his blessings throughout my life, as well as to many individuals and institutions for their moral and financial support; and I hereby extend to them my opportune appreciation. I wish to express my deepest thanks to Prof. H.G.van der Wilt for having accepted the idea of this thesis and for his learned guidance. -

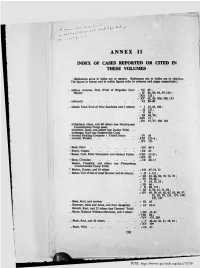

Annex Ii Index of Cases Reported Or Cited in These Volumes

J» ■ i, J L-, UJ> O'- ' / C , " i ANNEX II INDEX OF CASES REPORTED OR CITED IN THESE VOLUMES (References given in italics arc to reports. References not in italics are to citations. The figures in roman and in arabic figures refer to volumes and pages respectively.) Abbaye Ardcnnc Trial (Trial of Brigadier Kurt~ 111 6 9 ; Meyer). ✓ IV 85, 89, 997-110 5 , ; *X1I 123: ✓ X V 62, ¿4, 106,109, 133 - Ahlbrecht ......................................................... X I 89-90 « Almelo Trial (Trial or Otto Sandrock and 3 others)✓ / 35-45,1 0 6 ; ✓ 11 127; w V 1 0 ; . XI 46,50; . X IV 15 ; * X V 47, 97, 108, 184 Allfuldisch, Hans, and 60 others (sec Mauthausen Concentration Camp case). Altstötter, Josef, and others (sec Justkc Trial) .. Ambcrgcr, Karl (sec Dreierwalde Case) - Armour Packing Company v. United States .. s W 54 - Awochi, Washio ..............................................^Xlll 122-4 ; X V 121 » Back, P e t e r ........................................................ ✓/// 60-1 x Bauer, August ..............................................«'IX 65 v Bauer, Carl, Ernst Schramcck and Herbert Falten*Vlll 15-21; v X V 82 v'Baus, Christian ..............................................s l X 68-71 Becker, Friedrich, and others (sec Flossenberg Concentration Camp Trial) t'Becker, Gustav, and 19 others ........................ JVU 67-73,15 ✓ Belsen Trial (Trial of Josef Kramer and 44 others)..11 1-152;✓ ✓ III 6 3 ,6 6 ,6 9 .7 0 ,7 2 ,7 4 ; ✓ IV 79,86 ; ✓ V 14, 15, 23 ; ✓ IX 66 ; ✓ X 68, 173 ; ✓ XI 9,10,11,71,83; ✓ X V 45, 59, 61, 65, 67, 83, 86, 87, 92, 93, 97, 121. -

Some International Law Problems Related to Prosecutions Before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

SOME INTERNATIONAL LAW PROBLEMS RELATED TO PROSECUTIONS BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA W.J. FENRICK* I. INTRODUCTION The presentation of prosecution cases before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (the Tribunal) will require argument on a wide range of international law issues. It will not be possible, and it would not be desirable, simply to dust off the Nuremberg and Tokyo Judgments, the United Nations War Crimes Commission series of Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, and the U.S. government's Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No.10 and presume that one has a readily available source of answers for all legal problems. An invaluable foundation for legal argument before the Tribunal is provided by Pictet's Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the International Committee of the Red Cross' (ICRC) Commentaries on the Additional Protocols of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the few cases decided since 1950, old case law, and various learned articles and treatises. They must be reviewed and analyzed. At the same time, however, just as the prosecutors in the post-1945 war crimes trials argued successfully that customary law had evolved after 1907 and 1929, so it is reasonable to presume that customary law has evolved since the Geneva Convention of 1949 and the Additional Protocols of 1977. It is essential to pay due heed to the principles of nullum crimen sine lege and nulla poena sine lege.1 One must, however, distinguish * Senior Legal Advisor, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

Contents Preface xxiii Abbreviations and Acronyms xxvii Acknowledgments xxxiii Foreword xxxvii part I Why 1 chapter 1 Foundations 3 A. Purposes 5 1. Protection of Civilians and Others Hors de Combat 7 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 8 2. Minimize Unnecessary Suff ering 9 3. Mission Fulfi llment 10 B. Key Sources of LOAC 11 1. Treaties 11 2. Customary International Law 13 David J. Bederman, International Law Frameworks 13 C. Jus ad Bellum vs. Jus in Bello 16 1. Jus ad Bellum 16 2. Jus ad Bellum in an Age of Counterterrorism 21 3. Separation of Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello 23 Prosecutor v. Fofana and Kondewa 25 Questions for Discussion 27 xi xii Contents D. Intersection with and Distinction from Human Rights Law 30 Th eodor Meron, Th e Humanization of Humanitarian Law 30 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 32 Fourth Periodic Report of the United States of America to the United Nations Committee on Human Rights Concerning the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 34 Questions for Discussion 37 chapter 2 Basic Principles 39 Jean Pictet, Development and Principles of International Humanitarian Law 39 A. Military Necessity 40 Th e United States of America v. Wilhelm List et al. (Th e Hostages Trial) 42 Questions for Discussion 44 B. Humanity 45 Questions for Discussion 47 C. Distinction 48 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 50 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 52 Questions for Discussion 53 D. Proportionality 56 Questions for Discussion 59 chapter 3 Historical Development of LOAC 61 A. -

The Case of Military Occupation', the Journal of Modern History, Vol

University of Birmingham International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949 Gumz, Jonathan DOI: 10.1086/698960 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Gumz, J 2018, 'International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949: the case of military occupation', The Journal of Modern History, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 621-660. https://doi.org/10.1086/698960 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: © 2018 by The University of Chicago General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

LAW MANTRA THINK BEYOND OTHERS (I.S.S.N 2321- 6417 (Online) Ph: +918255090897 Website: Journal.Lawmantra.Co.In E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected]

LAW MANTRA THINK BEYOND OTHERS (I.S.S.N 2321- 6417 (Online) Ph: +918255090897 Website: journal.lawmantra.co.in E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] SUPERIOR ORDERS AND DEFENCE OF MISTAKE INTRODUCTION CONFLICT IN THE IDEOLOGIES BEHIND DEFENCE OF SUPERIOR ORDERS There has for long been a conflict on whether the act of the soldier shall impose criminal liability or not. It is because there are two policies that arise on keenly studying the liability. Both the policies are beneficial to the community of mankind.1One policy complies to the discipline in military forces and the other with the adherence to Law of war which lays down principles of peace. The underlying theme of both the policies is that in one case, it is expected that the sub- ordinate voluntarily not obey an order, and the other requires obeyance.2The two extreme, opposite theories are described3 as follows: DOCTRINE OF RESPONDEAT SUPERIOR The doctrine signifies the lack of responsibility on sub-ordinate’s part since, the act that he had committed was in pursuance of the order by his superior. This view is deemed fit in the case of Armed Forces.4 Since, the Armed Forces require discipline, that is the superiors be obeyed .Such a principle is used to conduct the men to battle, and lead them to victory, even at the risk of their lives. Human psychology works on selfish motives and self-preservation.5 However, as a part of military discipline, soldiers have to keep aside their selfish motives, accomplish the military objective, emerge victorious, preserve life of other soldiers and protect the national security.