SOME ASPECTS of AUSTRALITE DISTRIBUTION PATTERN in WESTERN AUSTRALIA Download 2.22 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

Planetary Surfaces

Chapter 4 PLANETARY SURFACES 4.1 The Absence of Bedrock A striking and obvious observation is that at full Moon, the lunar surface is bright from limb to limb, with only limited darkening toward the edges. Since this effect is not consistent with the intensity of light reflected from a smooth sphere, pre-Apollo observers concluded that the upper surface was porous on a centimeter scale and had the properties of dust. The thickness of the dust layer was a critical question for landing on the surface. The general view was that a layer a few meters thick of rubble and dust from the meteorite bombardment covered the surface. Alternative views called for kilometer thicknesses of fine dust, filling the maria. The unmanned missions, notably Surveyor, resolved questions about the nature and bearing strength of the surface. However, a somewhat surprising feature of the lunar surface was the completeness of the mantle or blanket of debris. Bedrock exposures are extremely rare, the occurrence in the wall of Hadley Rille (Fig. 6.6) being the only one which was observed closely during the Apollo missions. Fragments of rock excavated during meteorite impact are, of course, common, and provided both samples and evidence of co,mpetent rock layers at shallow levels in the mare basins. Freshly exposed surface material (e.g., bright rays from craters such as Tycho) darken with time due mainly to the production of glass during micro- meteorite impacts. Since some magnetic anomalies correlate with unusually bright regions, the solar wind bombardment (which is strongly deflected by the magnetic anomalies) may also be responsible for darkening the surface [I]. -

Terrestrial Impact Structures Provide the Only Ground Truth Against Which Computational and Experimental Results Can Be Com Pared

Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1987. 15:245-70 Copyright([;; /987 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved TERRESTRIAL IMI!ACT STRUCTURES ··- Richard A. F. Grieve Geophysics Division, Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario KIA OY3, Canada INTRODUCTION Impact structures are the dominant landform on planets that have retained portions of their earliest crust. The present surface of the Earth, however, has comparatively few recognized impact structures. This is due to its relative youthfulness and the dynamic nature of the terrestrial geosphere, both of which serve to obscure and remove the impact record. Although not generally viewed as an important terrestrial (as opposed to planetary) geologic process, the role of impact in Earth evolution is now receiving mounting consideration. For example, large-scale impact events may hav~~ been responsible for such phenomena as the formation of the Earth's moon and certain mass extinctions in the biologic record. The importance of the terrestrial impact record is greater than the relatively small number of known structures would indicate. Impact is a highly transient, high-energy event. It is inherently difficult to study through experimentation because of the problem of scale. In addition, sophisticated finite-element code calculations of impact cratering are gen erally limited to relatively early-time phenomena as a result of high com putational costs. Terrestrial impact structures provide the only ground truth against which computational and experimental results can be com pared. These structures provide information on aspects of the third dimen sion, the pre- and postimpact distribution of target lithologies, and the nature of the lithologic and mineralogic changes produced by the passage of a shock wave. -

2021 2021Course Guide Course Guide Exmouth

2021 2021COURSE GUIDE COURSE GUIDE EXMOUTH CARNARVON GERALDTON BATAVIA COAST MARITIME INSTITUTE Contents TECHNOLOGY PARK IT ALL STARTS HERE 2 MOORA At Central Regional TAFE we’ll help you find your career, find your calling, find your start. KALGOORLIE MERREDIN LET’S GET THE FACTS 4 NORTHAM Why choose Vocational Education & Training? LEARN BY DOING 5 Simulated workplace learning HELPING YOU SUCCEED 6 Contact us Student Services 1800 672 700 JOBS & SKILLS CENTRES 7 [email protected] We can make it easier! centralregionaltafe.wa.edu.au WHERE ARE YOU HEADING? 8 VETDSS, PAIS, Pre-Apprenticeship, Apprenticeship/ Traineeship, University Pathways, Qualifications Batavia Coast Kalgoorlie Maritime Institute 34 Cheetham St 133 Separation Point Cl Kalgoorlie WA 6430 GET STRAIGHT INTO IT 10 Geraldton WA 6530 Pre-apprenticeships, Apprenticeships & Traineeships Merredin Carnarvon 42 Throssell Rd FOR ALL YOUR TRAINING NEEDS 11 14 Camel Ln Merredin WA 6415 Workforce solutions Carnarvon WA 6701 Moora Exmouth 242 Berkshire Valley Rd MAKING TRAINING AFFORDABLE 12 Ningaloo Centre Moora WA 6510 Don’t put your future on hold Cnr Murat Rd & Truscott Cres Northam Exmouth WA 6707 GET SKILLS READY 13 LOT 1 Hutt St There’s never been a better time to get into training Geraldton Northam WA 6401 173 – 175 Fitzgerald St Technology Park Geraldton WA 6530 STUDY OPTIONS FOR ALL 14 Cnr Deepdale Rd & What study mode suits you? Arthur Rd Geraldton WA 6532 THE NEXT STEP 15 How to enrol CRTAFE acknowledges the Aboriginal peoples of the Midwest, Gascoyne, Wheatbelt and Goldfields regions as traditional custodians COURSE INDEX 67 of the lands and waters. -

NEW HIGH-PRECISION POTASSIUM ISOTOPES of TEKTITES. Y. Jiang1,2, H

49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083) 1311.pdf NEW HIGH-PRECISION POTASSIUM ISOTOPES OF TEKTITES. Y. Jiang1,2, H. Chen2, B. Fegley, Jr.2, K. Lodders2, W. Hsu3, S. B. Jacobsen4, K. Wang (王昆)2. 1CAS Key Laboratory of Planetary Sciences, Purple Moun- tain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences ([email protected]), 2Dept. Earth & Planetary Sciences and McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis ([email protected]), 3Space Sci- ence Institute, Macau University of Science and Technology, 4Dept. Earth & Planetary Sciences, Harvard University. Introduction: Tektites are natural glassy objects crater of Hawaii (BHVO-1), are also analyzed. Hainan formed from the melting and rapid cooling of terrestri- Tektite is a typical splash-form tektite from Hainan al rocks during the high-energy impacts of meteorites, Island, China and of a dumbbell shape. We analyzed K comets, or asteroids upon the surface of the Earth [1]. isotopes of 15 chips along the longitudinal axis of its Chemical and isotopic compositions indicate that pre- profile, on a Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS at Washington cursor components of tektites are the upper terrestrial University in St. Louis [14]. Except for Hainan tektite, continental crust, rather than extraterrestrial rocks. all other samples were only analyzed in bulk, with a Tektites are characterized by the depletion of volatile GV Instruments IsoProbe P MC-ICP-MS at Harvard elements and water, and heavy Cd, Sn, Zn and Cu iso- University following the description in [13]. K isotope topic compositions [2-5]. Since volatilities of elements compositions are reported using the per mil (‰) nota- 41 41 39 41 39 are defined by their 50% condensation temperature (Tc) tion, where δ K = ([( K/ K)sample/( K/ K)standard – of the solar nebula gas at 10-4 bars [6], there is no rea- 1]×1000). -

Australian Exchange (Kalgoorlie) 2017

Australian Exchange (Kalgoorlie) 2017 Erena Hosford—RMIP Wairarapa We are all visitors to this time, this place. We are just passing through. Our purpose here is to observe, to learn, to grow, to love… and then we return home. – Australian Aboriginal Proverb The super pit In July 2017 I was lucky enough to be given the opportunity to be placed in rural Western Australia for two weeks of my 5th year medical training. I was placed at Kalgoorlie Hospital in the city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, which is in the goldfields 595km inland from Perth. The town has a population of over 32,000 people and was founded in 1893 during the gold rush. The largest employer in the area is the ‘Super pit’, an open cut gold mine, which is over 3 km long. The evening my fellow RMIP classmate and I landed in Kalgoorlie we were greeted at the airport by staff from the medical school who took us to our accommodation. There we met some of the Australian rural medical students. They had just started their mid year break but were still happy to take us out for dinner and show us around the town. The next day we started at the hospital. Kalgoorlie Hospital has an incredibly large catchment area, with some patients having travelled over 900km to attend clinics. While in Kalgoorlie I was on the Paediatric and General Medicine teams. I found the medicine there to be really interesting. There were many indigenous Australian patients, as well as a surprisingly large amount of New Zealanders (who move to Kalgoorlie to work in the mines). -

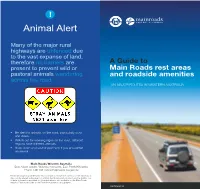

A Guide to Main Roads Rest Areas and Roadside Amenities

! Animal Alert Many of the major rural highways areunfenced due to the vast expanse of land, thereforeno barriers are A Guide to present to prevent wild or Main Roads rest areas pastoral animals wandering and roadside amenities across the road. ON MAJOR ROUTES IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Be alert for animals on the road, particularly dusk and dawn. Watch out for warning signs on the road, different regions have different animals. Slow down and sound your horn if you encounter an animal. MWain Roads estern Australia Don Aitken Centre ,, Waterloo Crescent East Perth WA 6004 Phone138 138 | www.mainroads.wa.gov.au Please be aware that while every effort is made to ensure the currency of the information, data can be altered subsequent to original distribution and can also become quickly out- of-date. Information provided on this publication is also available on the Main Roads website. Please subscribe to the Rest Areas page for any updates. MARCH 2015 Fatigue is a silent killer on Western Australian roads. Planning ahead is crucial to managing fatigue on long A roadside stopping place is an area beside the road road trips. designed to provide a safe place for emergency stopping or special stopping (e.g. rest areas, scenic lookouts, Distances between remote towns can information bays , road train assembly areas). Entry signs indicate what type of roadside stopping place it is. Facilities be vast and in some cases conditions within each vary. can be very hot and dry with limited fuel, water and food available. 24 P Rest area 24 hour Information Parking We want you to enjoy your journey rest area but more importantly we want you to stay safe. -

Submission of Form BA20 Notice of Consent to the Department of Housing

Submission of Form BA20 Notice of Consent to the Department of Housing The following contact details should be used in relation to obtaining written consent from the Department of Housing as the adjoining property owner along a shared property boundary. 1. Where the Department of Housing property is occupied or construction has been completed the attached list of suburbs should be used to identify the Regional Office responsible for that suburb. The Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation should be submitted to the Regional Manager using the details provided for that particular office. 2. Where construction has not yet commenced on the Department of Housing property or where construction is still in progress then the Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation should be submitted to the Manager Professional Services using the details provided. NOTE – Approval will be delayed if the Notice of Consent Form BA20 and relevant documentation is not submitted to the correct processing area. -

The 3D.Y Knom Example Is /1"<

t Sixth International Congress on Glass - Washington, D. C., 1962. Fossil Glasses Produced by Inpact of Meteorites, Asteroids 2nd Possibly Comets with the Planet Xarth* A. J. Zzhen :&uon Insticute, Pittsburgh, ?ennsylvania (U. S. A. ) Sunnary / (to be trmslzted izto Frerzh and German) - i in recent thes one of the nost intriging aysteries of geGlogy has ceen the occurrence of aerodgnasicdly-shaped glasses on five continents of the earth. Tnese glasses mder discussion are obviously not of f-d- guritic origin. 3ecent research indicates that these glasses laom as tektites are the result of meteorite, esteroid, or sossibly comet hpact. Lqact glass?s, io generzl, differ Tram volcanic glasses in that they are lo;;.tr in ?,iater zontent, have laver gallium and germiun ccntents, and are rot necessarily ia mgnaticalljr unstable continental areas. These hpac- tites may be divided as follovs: (1)Glasses found in or near terrestrial neteorite craters. These glasses usually contain numerous s-,'nerules 02 nickel-iron, coesite, chunlks of partially melted meteoritic inatter and even stishovite. Shattered or fractured melted mi-nerals such as quarts are comxonly gresent. Aerodpaaic-shaping nay or nay not be present in this t-ne. &m?les are Canyon Diablo and Wabar Crster glasses. (2) Impzct- glasses zssociated with craters uitn no evidence of meteoritic mterial i? the @.ass or surrounding the explosisn site. The 3d.y knom example is /1"< Tnis vork vas supported by Xatiocal A-eroEautizs and Space P.dministretioq,$ 3esezrch Grant NsG-37-6O Supplement 1-62. Page 2 glass associated with AoueUoul Crater in the Western Sahara Desert. -

Investigating Possible Belize Tektites – Request of an Extended Database on Magnetic and Raman Spectroscopical Signature of Natural Glasses

47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2016) 2482.pdf INVESTIGATING POSSIBLE BELIZE TEKTITES – REQUEST OF AN EXTENDED DATABASE ON MAGNETIC AND RAMAN SPECTROSCOPICAL SIGNATURE OF NATURAL GLASSES. V.H. Hoffmann1,2, Kaliwoda M.3, Hochleitner R.3, M. Funaki4, M. Torii5. 1Faculty of Geosciences, Dep. Geo- and Envi- ronm. Sciences, Univ. Munich; 2Dep. Geosciences, Univ. Tuebingen, 3MSCM, Munich, Germany; 4Tokyo, Japan; 5Okayama, Japan. Introduction m (gr) MS (10-9 m3/kg) Log MS Since 1992 findings of possible tektite glasses have- Belize A 1.35 123.5 2.09 been reported from Tikal region, Guatemala, and later Belize 1 0.61 131.5 2.12 from Belize, here most likely in situ. Therefore the Belize 2 0.67 128.5 2.11 existence of a Central American tektite strewn field Belize 3 0.42 178.7 2.25 was proposed [1,2]. Ages of between 780 and 820 ± Belize 4 0.33 212.8 2.33 40 ka have been determined for Belize glasses [3-5]. The radiometric age constraints are indistinguishable Belize 5 0.53 168.3 2.23 from the ages of the Australite-Indochinite tektite Belize 6 0.52 195.4 2.29 strewn field (~770 ka). However, additional investiga- Belize 7 0.36 170.5 2.23 tions on Belize glasses reported different geochemical Belize 8 0.56 129.0 2.11 signatures in comparison to the Australite-Indochinite Range 123.5 – 212.8 2.09 – 2.33 tektites [6-10]. Pantasma structure in Nicaragua was Average 159.8 2.20 proposed as a possible impact crater [11]. -

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’S Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’S

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’s Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’s Western Australia PART 1. GWW NORTHERN Southern Cross Kalgoorlie Widgiemooltha birds are in our nature ® Australia AUSTRALIA Introduction The birds and places of the north-west region of the Great Western Woodlands are presented in this booklet. This area includes tall woodlands on red soils, shrublands on yellow sand plains and mallee on sand and loam soils. Landforms include large granite outcrops, Banded Ironstone Formation (BIF) Ranges, extensive natural salt lakes and a few freshwater lakes. The Great Western Woodlands At 16 million hectares, the Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is close to three quarters the size of Victoria and is the largest remaining intact area of temperate woodland in the world. It is located between the Western Australian Wheatbelt and the Nullarbor Plain. BirdLife Australia and The Nature Conservancy joined forces in 2012 to establish a long-term project to study the birds of this unique region and to determine how we can best conserve the woodland birds that occur here. Kalgoorlie 1 Groups of volunteers carry out bird surveys each year in spring and autumn to find out the species present, their abundance and to observe their behaviour. If you would like to know more visit http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/great-western-woodlands If you would like to participate as a volunteer contact [email protected]. All levels of experience are welcome. The following six pages present 48 bird species that typically occur in four different habitats of the north-west region of the GWW, although they are not restricted to these. -

Lechatelierite in Moldavite Tektites: New Analyses of Composition

52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2021 (LPI Contrib. No. 2548) 1580.pdf LECHATELIERITE IN MOLDAVITE TEKTITES: NEW ANALYSES OF COMPOSITION. Martin Molnár1, Stanislav Šlang2, Karel Ventura3. Kord Ernstson4.1Resselovo nám. 76, Chrudim 537 01, Czech Republic ([email protected]) 2Center of Materials and Nanotechnologies, University of Pardubice, 532 10 Pardubice, Czech Republic, [email protected] 3Faculty of Chemical Technology, University of Pardubice, 530 02 Pardubice, Czech Republic, [email protected]. 4University of Würzburg, D-97074 Würzburg, Deutschland ([email protected]) Introduction: Moldavites are tektites with a Experiments and Results: Experiments 1 and 2 - beautiful, mostly green discoloration and a very the boron question. The question of lowering the pronounced sculpture (Fig.1), which have been studied melting point and acid resistance led to the possibility many times e.g. [1-3]). of adding boron. The experiment 1 on a moldavite plate etched in 15%-HF to expose the lechatelierite was performed by laser ablation spectrometry and showed B2O3 concentration of >1%. In experiment 2, 38 g of lechatelierite fragments were then separated from 482 g of pure moldavite, and after the boron Fig. 1. Moldavites from Besednice analyzed in this content remained high (Tab. 2), the remaining carbon study. Scale bar 1 cm. was washed away. The analysis in Tab. 3 shows According to the most probable theory, they were remaining low boron content, which is obviously formed 14.5 million years ago together with the Ries bound to the carbon of the moldavites [8]. crater meteorite impact in Germany. They belong to the mid-European tektite strewn field and fell mostly in Bohemia.