The Monadnock Building, Technically Reconsidered 2. Journal Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013 2013 Lake Baha’i Glenview 41 Wilmette Temple Central Old 14 45 Orchard Northwestern 294 Waukegan Golf Univ 58 Milwaukee Sheridan Golf Morton Mill Grove 32 C O N T E N T S Dempster Skokie Dempster Evanston Des Main 2 Getting Around Plaines Asbury Skokie Oakton Northwest Hwy 4 Near the Hotels 94 90 Ridge Crawford 6 Loop Walking Tour Allstate McCormick Touhy Arena Lincolnwood 41 Town Center Pratt Park Lincoln 14 Chinatown Ridge Loyola Devon Univ 16 Hyde Park Peterson 14 20 Lincoln Square Bryn Mawr Northeastern O’Hare 171 Illinois Univ Clark 22 Old Town International Foster 32 Airport North Park Univ Harwood Lawrence 32 Ashland 24 Pilsen Heights 20 32 41 Norridge Montrose 26 Printers Row Irving Park Bensenville 32 Lake Shore Dr 28 UIC and Taylor St Addison Western Forest Preserve 32 Wrigley Field 30 Wicker Park–Bucktown Cumberland Harlem Narragansett Central Cicero Oak Park Austin Laramie Belmont Elston Clybourn Grand 43 Broadway Diversey Pulaski 32 Other Places to Explore Franklin Grand Fullerton 3032 DePaul Park Milwaukee Univ Lincoln 36 Chicago Planning Armitage Park Zoo Timeline Kedzie 32 North 64 California 22 Maywood Grand 44 Conference Sponsors Lake 50 30 Park Division 3032 Water Elmhurst Halsted Tower Oak Chicago Damen Place 32 Park Navy Butterfield Lake 4 Pier 1st Madison United Center 6 290 56 Illinois 26 Roosevelt Medical Hines VA District 28 Soldier Medical Ogden Field Center Cicero 32 Cermak 24 Michigan McCormick 88 14 Berwyn Place 45 31st Central Park 32 Riverside Illinois Brookfield Archer 35th -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

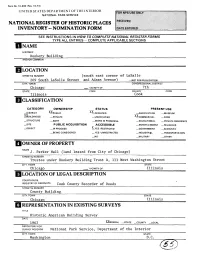

Iowner of Property Name J

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Rookery Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER (south east corner of LaSalle 209 South LaSalle Street and Adams Avenue) _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois Cook CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE vv _DISTRICT A1LOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM VV AmJILDING(S) _ PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED AACOMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME J. Parker Hall (land leased from City of Chicago) STREET & NUMBER Trustee under Rookery Building Trust A, 111 West Washington Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago VICINITY OF Illinois LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS'. Cook County Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER County BuiIding CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Building Survey DATE 1963 X)£EDERAL _STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Department of the Interior CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED XX_0 RIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XX.ALTERED _MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Completed in 1886 at a cost of $1,500,000, the Rookery contained 4,765,500 cubic feet of space. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Author: Kheir Al-Kodmany, University of Illinois at Chicago Subjects: Keyword: Social Media Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 8 Number 2 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. -

Wurlington Press Order Form Date

Wurlington Press Order Form www.Wurlington-Bros.com Date Build Your Own Chicago postcards Build Your Own New York postcards Posters & Books Quantity @ Quantity @ Quantity @ $ Chicago’s Tallest Bldgs Poster 19" x 28" 20.00 $ $ $ Water Tower Postcard AR-CHI-1 2.00 Flatiron Building AR-NYC-1 2.00 Louis Sullivan Doors Poster 18” x 24” 20.00 $ $ $ Chicago Tribune Tower AR-CHI-2 2.00 Empire State Building AR-NYC-2 2.00 Auditorium Bldg Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ $ $ AR-NYC-3 3.5” x 5.5” Wrigley Building AR-CHI-3 2.00 Citicorp Center 2.00 John Hancock Memo Book 4.95 $ $ $ AT&T Building AR-NYC-4 2.00 Pritzker Pavilion Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 Sears Tower AR-CHI-4 2.00 $ $ Rookery Memo Book 3.5” x 5.5” 4.95 $ Chrysler Building AR-NYC-5 2.00 John Hancock Center AR-CHI-5 2.00 $ $ American Landmarks Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 $ Lever House AR-NYC-6 2.00 AR-CHI-6 Reliance Building 2.00 $ $ U.S. Capitol Cut & Asssemble Book 9.95 AR-NYC-7 $ Seagram Building 2.00 Bahai Temple AR-CHI-7 2.00 $ $ Santa’s Workshop Cut & Asssemble Book 12.95 Woolworth Building AR-NYC-8 2.00 $ Marina City AR-CHI-9 2.00 Haunted House Cut & Asssemble Book $12.95 $ Lipstick Building AR-NYC-9 2.00 $ $ 860 Lake Shore Dr Apts AR-CHI-10 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Book 30.00 $ Hearst Tower AR-NYC-10 2.00 $ $ Lake Point Tower AR-CHI-11 2.00 Lost Houses of Lyndale Zines (per issue) 2.75 $ AR-NYC-11 UN Headquarters 2.00 $ $ Flood and Flotsam Book 16.00 Crown Hall AR-CHI-12 2.00 $ 1 World Trade Center AR-NYC-12 2.00 $ AR-CHI-13 35 E. -

CHICAGO Epicenter of American Architecture

May 29—June 3, 2021 CHICAGO Epicenter of American Architecture with Rolf Achilles Cloud Gate (Sir Anish Kapoor, 2006, Millennium Park) / Robert Lowe Chicago May 29—June 3, 2021 National Trust Tours returns to Chicago—a quintessential destination for architecture lovers—brought to you as only the National Trust can. Take an architectural cruise along the Chicago River, highlighting the many innovative and historically important architectural designs that were born in Chicago. See several Frank Lloyd Wright-designed buildings, including his own home and studio in Oak Park, Unity Temple, and the iconic Robie House. Enter Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, a masterpiece of design and elegant Modernist simplicity. Enjoy one of the finest private collections of decorative arts from the American and English Arts and Crafts Movements, showcased in the renovated farm buildings of a private estate. And take guided explorations of some of Chicago’s most intriguing and dazzling sites. (left) Chicago Vertical / Mobilus In Mobili Experience the iconic architectural spaces of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. (above) Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio / Esther Westerveld; (right) Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe CHICAGO Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright, Hyde Park, IL / Naotake Murayama HOTEL ACCOMMODATIONS: SUNDAY, MAY 30 America’s most promising Enjoy five nights in the heart of The Art Institute & and influential architects. the Loop at the legendary Palmer Tour Wright’s home and House Hilton, a member of Millennium Park studio, Historic Hotels of America. Walk to the Auditorium a National Trust Historic Theatre known internationally Site, and see where the SATURDAY, MAY 29 for its innovative architecture Prairie style was born. -

The Rookery Chicago Illinois

VOLUME 25 NUMBER 1 JANUARY-MARCH 1995 OFFICE THE ROOKERY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PROJECT TYPE An outstanding restoration of a historic, century-old, 12-story office building. The developer's strategy was to restore the 293,962-square-foot building's historic architectural interiors on the ground and mezzanine levels and to incorporate state-of-the-art HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), electrical, elevator, security, and telecommunications systems into the upper floors of office space without losing the feeling of the old building. This project sets the standard for future commercial renovations and proves that the cost of expensive, high-quality restoration can be recovered in Class A rents. SPECIAL FEATURES Historic preservation Landmark office building Successful conversion of a vacant, deteriorated building into modern Class A office space DEVELOPER Baldwin Development Company 209 South LaSalle Street, Suite 400 Chicago, Illinois 60604 312-553-6100 OWNER Rookery Partners Limited Partnership 209 South LaSalle Street, Suite 400 Chicago, Illinois 60604 312-553-6100 RESTORATION ARCHITECT McClier Corporation 401 East Illinois, Suite 625 Chicago, Illinois 60611 312-836-7700 GENERAL DESCRIPTION Following one of the most extensive restorations of a historic office building ever undertaken, the 109-year-old Rookery Building, located in the heart of Chicago's financial district, has reclaimed its former splendor. With painstaking exactitude, Baldwin Development Company and its restoration architect have brought back elements of the Rookery's three eras—Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root's original 1886 design, Frank Lloyd Wright's 1905 modernization of the interior, and a 1931 remodeling by William Drummond—while at the same time renovating the office floors to compete with the most expensive, recently constructed office space inside Chicago's Loop. -

The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Invisible Triumph: The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 JAMES V. STRUEBER Ohio State University, AT1 JOHANNA HAYS Auburn University INTRODUCTION from Engineering Magazine, The World's Columbian Exposition (WCE) was the first world exposition outside of Europe and was to Thus has Chicago gloriously redeemed the commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of obligations incurred when she assumed the Columbus reaching the New World. The exhibition's task of building a World's Fair. Chicago's planners aimed at exceeding the fame of the 1889 businessmen started out to prepare for a Paris World Exposition in physical size, scope of finer, bigger, and more successful enter- accomplishment, attendance, and profitability.' prise than the world had ever seen in this With 27 million attending equaling approximately line. The verdict of the jury of the nations 40% of the 1893 US population, they exceeded of the earth, who have seen it, is that it the Paris Exposition in all accounts. This was partly is unquestionably bigger and undoubtedly accomplished by being open on Sundays-a much finer, and now it is assuredly more success- debated moral issue-the attraction of the newly ful. Great is Chicago, and we are prouder invented Ferris wheel, cheap quick nationwide than ever of her."5 transportation provided by the new transcontinental railroad system all helped to make a very successful BACKGROUND financial plans2Surprisingly, the women's contribu- tion to the exposition, which included the Woman's Labeled the "White City" almost immediately, for Building and other women's exhibits accounted for the arrangement of the all-white neo-Classical and 57% of total exhibits at the exp~sition.~In addition neo-High Renaissance architectural style buildings railroad development to accommodate the exposi- around a grand court and fountain poolI6 the WCE tion, set the heart of American trail transportation holds an ironic position in American history. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist. -

Office Buildings of the Chicago School: the Restoration of the Reliance Building

Stephen J. Kelley Office Buildings of the Chicago School: The Restoration of the Reliance Building The American Architectural Hislorian Carl Condit wrote of exterior enclosure. These supporting brackets will be so ihe Reliance Building, "If any work of the structural arl in arranged as to permit an independent removal of any pari the nineteenth Century anticipated the future, it is this one. of the exterior lining, which may have been damaged by The building is the Iriumph of the structuralist and funclion- fire or otherwise."2 alist approach of the Chicago School. In its grace and air- Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney is widely rec- iness, in the purity and exactitude of its proportions and ognized as the innovator of the application of the iron details, in the brilliant perfection of ils transparent eleva- frame and masonry curtain wall for skyscraper construc- tions, it Stands loday as an exciting exhibition of the poten- tion. The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885, lial kinesthetic expressiveness of the structural art."' The exhibited the essentials of the fully-developed skyscraper Reliance Building remains today as the "swan song" of the on its main facades with a masonry curtain wall.' Span• Chicago School. This building, well known throughout the drei beams supported the exterior walls at the fourth, sixth, world and lisled on the US National Register of Historie ninth, and above the tenth levels. These loads were Irans- Places, is presenlly being restored. Phase I of this process ferred to stone pier footings via the metal frame wilhout which addresses the exterior building envelope was com- load-bearing masonry walls.'1 The strueture however had pleted in November of 1995. -

Columbian Exposition Long Version

THE WORLD’S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION OF 1893 QUEST CLUB PAPER JANUARY 7, 2011 JOHN STAFFORD 2 3 THE WORLD’S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION OF 1893 QUEST CLUB PAPER JANUARY 7, 2011 JOHN STAFFORD Introduction It is my pleasure to have been able to research and now deliver this paper on the World’s Columbian Exposition that was held in Chicago during the summer of 1893. I offer a sincere thank you to Bill Johnson for having proposed the topic. My father was born in Chicago and was raised just a few blocks from the site of the Exposition. I too was born in the Windy City and spent the first eight years of my childhood there. My academic training and profession is that of a “city planner” and, in so many respects, the Columbian Exposition is one of the historic landmarks of city planning in the United States. Daniel Burnham, who was a seminal figure in the design of the Fair, is generally regarded as one of the early pioneers of the profession. I anticipated enjoying the research, and I certainly was not disappointed. I suspect that many of you in the audience today have read The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson. It was Quester Karen Goldner who recommended the book to me several years ago. I devoured it then and did so a second time in preparing this paper. But as Cheryl Taylor cautioned, just using the Devil in the White City for background would be way too easy for a Quest paper. I did do much additional reading, but I must admit no one comes close to bringing the Exposition and its characters to life than does Larson and his research was spot on.