Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ninety Years of X-Ray Spectroscopy in Italy 1896-1986

Ninety years of X-ray spectroscopy in Italy 1896-1986 Vanda Bouché1,2, Antonio Bianconi1,3,4 1 Rome Int. Centre Materials Science Superstripes (RICMASS), Via dei Sabelli 119A, 00185Rome, Italy 2 Physics Dept., Sapienza University of Rome, P.le A. Moro 2, 00185 Rome, Italy 3 Institute of Crystallography of Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, IC-CNR, Montero- tondo, Rome, Italy 4 National Research Nuclear University MEPhI (Moscow Engineering Physics Institute), Kashirskoeshosse 31, 115409 Moscow, Russia Ninety years of X-ray spectroscopy research in Italy, from the X-rays dis- covery (1896), and the Fermi group theoretical research (1922-1938) to the Synchrotron Radiation research in Frascati from 1963 to 1986 are here summarized showing a coherent scientific evolution which has evolved into the actual multidisciplinary research on complex phases of condensed mat- ter with synchrotron radiation 1. The early years of X-ray research The physics community was very quick to develop an intense research in Italy on X rays, after the discovery on 5th January, 1896 by Röngten in Munich. Antonio Garbasso in Pisa [1], and then in Rome Alfonso Sella, with Quirino Majorana, Pietro Blaserna and Garbasso, published several papers on Nuovo Cimento [2], starting the Italian experimental school on X-rays research in XIX century [3]. The focus was on the mechanism of the emission by the X-ray tubes, the nature of X-rays (wave or particles), the propagation characteristics in the matter, the absorption and diffusion. Cambridge and Edinburgh at the beginning of the XX century became the world hot spots of X-ray spectroscopy with Charles Barkla who demonstrated the electromagnetic wave nature of X-ray propagation in the vacuum, similar with light and Henry Moseley, who studied the X-ray emission spectra, recorded the X-ray emission lines of most of the elements of the Mendeleev atomic table. -

James D. Watson Molecular Biologist, Nobel Laureate ( 1928 – )

James D. Watson Molecular biologist, Nobel Laureate ( 1928 – ) Watson is a molecular biologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the struc- ture of DNA. Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Watson was born in Chicago, and early on showed his brilliance, appearing on Quiz Kids, a popular radio show that challenged precocious youngsters to answer ques- tions. Thanks to the liberal policy of University of Chicago president ROBERT HUTCHINS, Watson was able to enroll there at the age of 15, earning a B.S. in Zoology in 1947. He was attracted to the work of Salvador Luria, who eventually shared a Nobel Prize with Max Delbrück for their work on the nature of genetic mutations. In 1948, Watson began research in Luria’s laboratory and he received his Ph.D. in Zoology at Indiana University in 1950 at age 22. In 1951, the chemist Linus Pauling published his model of the protein alpha helix, find- ings that grew out of Pauling’s relentless efforts in X-ray crystallography and molecu- lar model building. Watson now wanted to learn to perform X-ray diffraction experi- ments so that he could work to determine the structure of DNA. Watson and Francis Crick proceeded to deduce the double helix structure of DNA, which they submitted to the journal Nature and was subsequently published on April 25, 1953. Watson subsequently presented a paper on the double helical structure of DNA at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Viruses in early June 1953. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

DNA: the Timeline and Evidence of Discovery

1/19/2017 DNA: The Timeline and Evidence of Discovery Interactive Click and Learn (Ann Brokaw Rocky River High School) Introduction For almost a century, many scientists paved the way to the ultimate discovery of DNA and its double helix structure. Without the work of these pioneering scientists, Watson and Crick may never have made their ground-breaking double helix model, published in 1953. The knowledge of how genetic material is stored and copied in this molecule gave rise to a new way of looking at and manipulating biological processes, called molecular biology. The breakthrough changed the face of biology and our lives forever. Watch The Double Helix short film (approximately 15 minutes) – hyperlinked here. 1 1/19/2017 1865 The Garden Pea 1865 The Garden Pea In 1865, Gregor Mendel established the foundation of genetics by unraveling the basic principles of heredity, though his work would not be recognized as “revolutionary” until after his death. By studying the common garden pea plant, Mendel demonstrated the inheritance of “discrete units” and introduced the idea that the inheritance of these units from generation to generation follows particular patterns. These patterns are now referred to as the “Laws of Mendelian Inheritance.” 2 1/19/2017 1869 The Isolation of “Nuclein” 1869 Isolated Nuclein Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss researcher, noticed an unknown precipitate in his work with white blood cells. Upon isolating the material, he noted that it resisted protein-digesting enzymes. Why is it important that the material was not digested by the enzymes? Further work led him to the discovery that the substance contained carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and large amounts of phosphorus with no sulfur. -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

Genes, Genomes and Genetic Analysis

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION UNIT 1 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORDefining SALE OR DISTRIBUTION and WorkingNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION with Genes © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Chapter 1 Genes, Genomes, and Genetic Analysis Chapter 2 DNA Structure and Genetic Variation © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Molekuul/Science Photo Library/Getty Images. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284136609_CH01_Hartl.indd 1 08/11/17 8:50 am © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC -

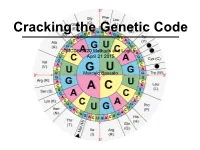

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

Happy Birthday to Renato Dulbecco, Cancer Researcher Extraordinaire

pbs.org http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/happy-birthday-renato-dulbecco-cancer-researcher-extraordinaire/ Happy birthday to Renato Dulbecco, cancer researcher extraordinaire Photo of Renato Dulbecco (public domain) Every elementary school student knows that Feb. 22 is George Washington’s birthday. Far fewer (if any) know that it is also the birthday of the Nobel Prize-winning scientist Renato Dulbecco. While not the father of his country — he was born in Italy and immigrated to the United States in 1947 — Renato Dulbecco is credited with playing a crucial role in our understanding of oncoviruses, a class of viruses that cause cancer when they infect animal cells. Dulbecco was born in Catanzaro, the capital of the Calabria region of Italy. Early in his childhood, after his father was drafted into the army during World War I, his family moved to northern Italy (first Cuneo, then Turin, and thence to Liguria). A bright boy, young Renato whizzed through high school and graduated in 1930 at the age of 16. From there, he attended the University of Turin, where he studied mathematics, physics, and ultimately medicine. Dulbecco found biology far more fascinating than the actual practice of medicine. As a result, he studied under the famed anatomist, Giuseppe Levi, and graduated at age 22 in 1936 at the top of his class with a degree in morbid anatomy and pathology (in essence, the study of disease). Soon after receiving his diploma, Dr. Dulbecco was inducted into the Italian army as a medical officer. Although he completed his military tour of duty by 1938, he was called back in 1940 when Italy entered World War II. -

Renato Dulbecco

BIOLOGIE ET HISTOIRE Renato Dulbecco Renato Dulbecco : de la virologie à la cancérologie F.N.R. RENAUD 1 résumé Né en Italie, Renato Dulbecco fait de brillantes études médicales mais est plus intéressé par la recherche en biologie que par la pratique médicale. Accueilli par Giuseppe Levi, il apprend l’histologie et la culture cellulaire avant de rejoindre le laboratoire de S.E. Luria puis celui de M. Delbrück pour travailler sur les systèmes bactéries-bactériophages puis sur la relation cellules-virus. Il met au point la méthode des plages de lyse virales sur des cultures cellulaires. Il est aussi à l’origine de la virologie tumorale moléculaire. D. Baltimore, HM Temin et lui-même sont récompensés par le prix Nobel de médecine et physiologie en 1975 pour leurs travaux sur l'interaction entre les virus tumoraux et le matériel génétique du matériel cellulaire. Très tourné vers les aspects pratiques et expérimentaux de la recherche, il est resté le plus long - temps possible à la paillasse et a initié un très grand nombre de jeunes chercheurs. mots-clés : culture cellulaire, virologie tumorale, plages de lyse, bactériophages. I. - LA JEUNESSE DE RENATO DULBECCO C'est à Catanzaro, capitale régionale de la Calabre en Italie, que naît Renato Dulbecco le 22 février 1914. Sa mère est Calabraise et son père Ligurien. Il ne reste que très peu de temps dans le sud de l’Italie, car son père est mobilisé et sa famille doit déménager dans le nord à Cuneo, puis à Turin. À la fin de la guerre, la famille Dulbeco s'ins - talle à Imperia en Ligurie. -

The Eighth Day of Creation”: Looking Back Across 40 Years to the Birth of Molecular Biology and the Roots of Modern Cell Biology

“The Eighth Day of Creation”: looking back across 40 years to the birth of molecular biology and the roots of modern cell biology Mark Peifer1 1 Department of Biology and Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB#3280, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3280, USA * To whom correspondence should be addressed Email: [email protected] Phone: (919) 962-2272 1 Forty years ago, Horace Judson’s “The Eight Day of Creation” was published, a book vividly recounting the foundations of modern biology, the molecular biology revolution. This book inspired many in my generation. The anniversary provides a chance for a new generation to take a look back, to see how science has changed and hasn’t changed. Many central players in the book, including Sydney Brenner, Seymour Benzer and Francois Jacob, would go on to be among the founders of modern cell, developmental, and neurobiology. These players come alive via their own words, as complex individuals, both heroes and anti-heroes. The technologies and experimental approaches they pioneered, ranging from cell fractionation to immunoprecipitation to structural biology, and the multidisciplinary approaches they took continue to power and inspire our work today. In the process, Judson brings out of the shadows the central roles played by women in many of the era’s discoveries. He provides us with a vision of how science and scientists have changed, of how many things about our endeavor never change, and how some new ideas are perhaps not as new as we’d like to think. 2 In 1979 Horace Judson completed a ten-year project about cell and molecular biology’s foundations, unveiling “The Eighth Day of Creation”, a book I view as one of the most masterful evocations of a scientific revolution (Judson, 1979). -

Toward a Scientific and Personal Biography of Tullio Levi-Civita (1873-1941) Pietro Nastasi, Rossana Tazzioli

Toward a scientific and personal biography of Tullio Levi-Civita (1873-1941) Pietro Nastasi, Rossana Tazzioli To cite this version: Pietro Nastasi, Rossana Tazzioli. Toward a scientific and personal biography of Tullio Levi-Civita (1873-1941). Historia Mathematica, Elsevier, 2005, 32 (2), pp.203-236. 10.1016/j.hm.2004.03.003. hal-01459031 HAL Id: hal-01459031 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01459031 Submitted on 7 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Towards a Scientific and Personal Biography of Tullio Levi-Civita (1873-1941) Pietro Nastasi, Dipartimento di Matematica e Applicazioni, Università di Palermo Rossana Tazzioli, Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica, Università di Catania Abstract Tullio Levi-Civita was one of the most important Italian mathematicians in the early part of the 20th century, contributing significantly to a number of research fields in mathematics and physics. In addition, he was involved in the social and political life of his time and suffered severe political and racial persecution during the period of Fascism. He tried repeatedly and in several cases successfully to help colleagues and students who were victims of anti-Semitism in Italy and Germany. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr.