YESTERDAY IS NOT TODAY New World Records 80243 the American Art Song 1930-1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eclectic Careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska

Interpreting success and failure: The eclectic careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ©2009 Anita Slominska Abstract My dissertation explores the eclectic singing careers of sisters Eva and Juliette Gauthier. Born in Ottawa, Eva and Juliettte were aided in their musical aspirations by the patronage of Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier and his wife Lady Zoë. They both received classical vocal training in Europe. Eva spent four years in Java. She studied the local music, which later became incorporated into her concert repertoire in North America. She went on to become a leading interpreter of modern art song. Juliette became a performer of Canadian folk music in Canada, the United States and Europe, aiming to reproduce folk music “realistically” in a concert setting. My dissertation is the result of examining archival materials pertaining to their careers, combined with research into the various social and cultural worlds they traversed. Eva and Juliette’s careers are revealing of a period of transition in the arts and in social experience more generally. These transitions are related to the exploitation of non-Western people, uses of the “folk,” and the emergence of a cultural marketplace that was defined by a mixture of highbrow institutions and mass culture industries. My methodology draws from the sociology of art and cultural history, transposing Eva and Juliette Gauthier against the backdrop of the social, cultural and economic conditions that shaped their career trajectories and made them possible. -

We Are Proud to Offer to You the Largest Catalog of Vocal Music in The

Dear Reader: We are proud to offer to you the largest catalog of vocal music in the world. It includes several thousand publications: classical,musical theatre, popular music, jazz,instructional publications, books,videos and DVDs. We feel sure that anyone who sings,no matter what the style of music, will find plenty of interesting and intriguing choices. Hal Leonard is distributor of several important publishers. The following have publications in the vocal catalog: Applause Books Associated Music Publishers Berklee Press Publications Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company Cherry Lane Music Company Creative Concepts DSCH Editions Durand E.B. Marks Music Editions Max Eschig Ricordi Editions Salabert G. Schirmer Sikorski Please take note on the contents page of some special features of the catalog: • Recent Vocal Publications – complete list of all titles released in 2001 and 2002, conveniently categorized for easy access • Index of Publications with Companion CDs – our ever expanding list of titles with recorded accompaniments • Copyright Guidelines for Music Teachers – get the facts about the laws in place that impact your life as a teacher and musician. We encourage you to visit our website: www.halleonard.com. From the main page,you can navigate to several other areas,including the Vocal page, which has updates about vocal publications. Searches for publications by title or composer are possible at the website. Complete table of contents can be found for many publications on the website. You may order any of the publications in this catalog from any music retailer. Our aim is always to serve the singers and teachers of the world in the very best way possible. -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Les Forains – Ballet Urbain Anthony Egéa / Cie Rêvolution

Les Forains – Ballet Urbain Anthony Egéa / Cie Rêvolution D’après Les Forains d’Henri Sauget, sur un argument de Boris Kochno – Éditions Salabert Chorégraphie : Anthony Égéa Interprétation : Sofiane Benkamla, Antoine Bouiges, Simon Dimouro, Manuel Guillaud, Jérôme Luca, Amel Sinapayen, Maxim Thach et Aurélien Vaudey Partie orchestrale enregistrée par l’Orchestre de Limoges, sous la direction de Philippe Forget Musique électro : Frank2Louise Scénographie et lumières : Florent Blanchon Costumes : Hervé Poeydomenge Un ballet urbain au confluent du classique et du hip-hop, un métissage culturel festif et détonant ! La création originale des Forains, dont la musique est signée Henri Sauguet, est un court ballet en un acte qui, en 1945, lança la carrière du chorégraphe Roland Petit, peu de temps après la libération. L’Opéra de Limoges et la Cie Rêvolution ont souhaité remettre à l’honneur et au goût du jour cette « fête de la jeunesse et de la danse », comme Jean Cocteau a si bien décrit cette œuvre, célébrant à nouveau le thème intemporel des forains et des artistes de rue. Anthony Égéa s’est donc emparé de cette œuvre du répertoire académique et en a réalisé une création totalement hybride, ingénieux croisement entre le classique et le hip-hop. Les Forains de Sauguet prennent alors place dans notre société contemporaine, où la danse urbaine se mêle poétiquement à la musique orchestrale. En écho à la partition originale, un musicien électro répond par la texture du son synthétique, créant un subtil anachronisme des genres. Sans être figé dans une esthétique particulière, il s’agit bien d’un dialogue permanent entre les styles que ces artistes saltimbanques nous suggèrent le temps d’un ballet urbain. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

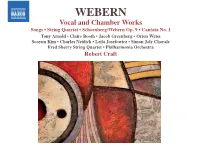

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 22:49 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility Christopher Dawson Volume 21, numéro 2, 2001 Résumé de l'article La pièce pour piano Vexations d’Erik Satie comporte une « Note de l’auteur » URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014483ar où le compositeur demande apparemment aux interprètes de répéter le DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar morceau 840 fois. Les opinions des biographes de Satie divergent quant à savoir si Satie voulait ou non une exécution « complète » de la pièce. Dans cet Aller au sommaire du numéro article, l’auteur évalue comment une interprétation littéraire de la Note peut jeter un éclairage sur les intentions de Satie. Il conclut que Vexations n’est pas tant un morceau de bravoure qu’un exercice : un moment musical conçu pour Éditeur(s) dégager les interprètes des notions occidentales conventionnelles de développement linéaire et de réception cumulative, en faveur d’un style Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités musical personnel d’où est absent le développement, et pour les préparer à canadiennes jouer d’autres pièces, telles une Gymnopédie ou une Gnossienne. ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dawson, C. (2001). Erik Satie's Vexations—An Exercise in Immobility. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 21(2), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014483ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D. -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

Eugene Ormandy Commercial Sound Recordings Ms

Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Ms. Coll. 410 Last updated on October 31, 2018. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2018 October 31 Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts Creator Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985