Dove Cottage: Words Worth's Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2015 Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800 Jason N. Goldsmith Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Jason N., "Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads, 1800" The Oxford Handbook of William Wordsworth / (2015): 204-220. Available at https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/876 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICAL BALLADS, 1800 205 [tha]n in studying German' (CL, r. 459). Stranded by the weather, short on cash, and C H A P TER 11 unable to communicate with the locals, the poet turned inward, writing a series of auto biographical blank verse fragments meditating on his childhood that would become part one of the 1799 Prelude, as well as nearly a dozen poems that would appear in the second volume of the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads. WORDSWORTH'S L YRICAL Completed over the eighteen months following his return to England in May 1799, the 1800 Lyrical Ballads is the fruit of that long winter abroad. It marks both a literal and BALLADS, 1800 a literary homecoming. Living in Germany made clear to Wordsworth that you do not ....................................................................................................... -

Grasmere & the Central Lake District

© Lonely Planet Publications 84 Grasmere & the Central Lake District The broad green bowl of Grasmere acts as a kind of geographical junction for the Lake District, sandwiched between the rumpled peaks of the Langdale Pikes to the west and the gentle hummocks and open dales of the eastern fells. But Grasmere is more than just a geological centre – it’s a literary one too thanks to the poetic efforts of William Wordsworth and chums, who collectively set up home in Grasmere during the late 18th century and transformed the valley into the spiritual hub of the Romantic movement. It’s not too hard to see what drew so many poets, painters and thinkers to this idyllic corner LAKE DISTRICT LAKE DISTRICT of England. Grasmere is one of the most naturally alluring of the Lakeland valleys, studded with oak woods and glittering lakes, carpeted with flower-filled meadows, and ringed by a GRASMERE & THE CENTRAL GRASMERE & THE CENTRAL stunning circlet of fells including Loughrigg, Silver Howe and the sculptured summit of Helm Crag. Wordsworth spent countless hours wandering the hills and trails around the valley, and the area is dotted with literary landmarks connected to the poet and his contemporaries, as well as boasting the nation’s foremost museum devoted to the Romantic movement. But it’s not solely a place for bookworms: Grasmere is also the gateway to the hallowed hiking valleys of Great and Little Langdale, home to some of the cut-and-dried classics of Lakeland walking as well as one of the country’s most historic hiking inns. -

The English Lake District

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum 10-1980 The nE glish Lake District La Salle University Art Museum James A. Butler Paul F. Betz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum; Butler, James A.; and Betz, Paul F., "The nE glish Lake District" (1980). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 90. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T/ie CEnglisti ^ake district ROMANTIC ART AND LITERATURE OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT La Salle College Art Gallery 21 October - 26 November 1380 Preface This exhibition presents the art and literature of the English Lake District, a place--once the counties of Westmorland and Cumber land, now merged into one county, Cumbria— on the west coast about two hundred fifty miles north of London. Special emphasis has been placed on providing a visual record of Derwentwater (where Coleridge lived) and of Grasmere (the home of Wordsworth). In addition, four display cases house exhibits on Wordsworth, on Lake District writers and painters, on early Lake District tourism, and on The Cornell Wordsworth Series. The exhibition has been planned and assembled by James A. -

William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820–1900

212 Book Reviews 最後に、何はともあれ、ワーズワスに関するミニ百科事典とも言うべき 『ワーズワス評伝』は一読に値する大著であることに間違いはない。 (安田女子大学教授) Saeko Yoshikawa William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820–1900 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. 156 × 234mm. xii + 268 pp. £65) Ichiro Koguchi Tourism is not just an embodiment of the natural human desire for move- ment and fresh experience. As Saeko Yoshikawa’s William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820–1900 has demonstrated, it is a set of culturally charged practices, mediated in particular by the act of reading. Grounded in this conviction, this study has explored — by referring to an impressive range of primary sources — how William Wordsworth’s poetry helped to invent a new form of tourism, and, through this process, how the notion of “Wordsworth’s Lake District” came into existence. The book also suggests that the emergence of such tourism was related to the critical re-evaluation of Wordsworth’s work in the late nineteenth century. Tourism has expanded throughout modern times. The grand tour fl our- ished from the mid-seventeenth century, and in the next century, picturesque travel came into vogue. With the development of the mail coach system, fol- lowed by the advent of the railway, tourism became universalised in the nine- teenth century, becoming available to almost any class and social group. Historically situated amid these periods, Romanticism was closely related to tourism, both domestic and across national borders. A number of schol- ars have turned to travelogues and other travel literature written in the Ro- mantic age, delving into the cultural-literary implications of journeys made by writers. Curiously however, literary tourism, i.e. -

3685 William Wordsworth

#3682 WILLIAM WORDSWORTH Grade Levels: 10-13+ 24 minutes BENCHMARK MEDIA 1998 DESCRIPTION Poet Tobias Hill examines the poetry of William Wordsworth as he treks in the Lake District of England, Wordsworth's home. Hill dialogs with others about what influenced Wordsworth and what kind of poet he was. Notes his poetry is concerned with nature, humans, and society. Excerpts from "The Rainbow," "The Prelude," "Lucy Gray," and others illustrate some of his themes. Addresses Wordsworth's poetry, not his life. INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To understand how closely the poetry of Wordsworth is derived from his own life experiences, and the natural landscape of his native Lake District in northwest England. 2. To appreciate how his creative imagination interprets what he has experienced. 3. To enjoy how the rhythms and language of his poetry are suitable to amplify and transform the subjects of his poetry. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Born in 1770, William Wordsworth remembered his childhood as a happy one, particularly his school days at Hawkshead. However, with the death of his parents while a teenager, he felt a loss of innocence, and an awareness of hardship and unhappiness. During his undergraduate days at St. John’s College, Cambridge, he took strenuous walking tours through France, Switzerland, and later, Germany. The ideals of liberty and brotherhood of the French Revolution, then in progress when he was there, became his. Consequently, he came to hate inherited rank and wealth. At a critical time in his youth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge became his neighbor, friend, and supporter. Apart from some tours abroad, Wordsworth remained in the Lake District of northwest England, which he dearly loved, from age 43 until his death at 80. -

Fay, J. (2018). Rhythm and Repetition at Dove Cottage. Philological Quarterly, 97(1), 73-95

Fay, J. (2018). Rhythm and repetition at Dove Cottage. Philological Quarterly, 97(1), 73-95. https://english.uiowa.edu/philological- quarterly/abstracts-971 Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ RHYTHM AND REPETITION AT DOVE COTTAGE JESSICA FAY Abstract It is well known that William and Dorothy Wordsworth habitually hummed and murmured lines of poetry to themselves and to each other both indoors and while they paced backwards and forwards outside. While this was a lifelong habit for the poet, there are two specific periods at Dove Cottage—the spring and early summer of 1802 and the months following John Wordsworth’s death in 1805—during which the repetition of verses alongside various types of iterative physical activity may be interpreted as an “extra-liturgical” practice performed to induce and support meditation and consolation. In shaping their own “familiar rhythm[s]”, the Wordsworths are aligned with Jeremy Taylor, whose mid-seventeenth- century writings promoted the cultivation of private, individual repetition and ritual. Although William and Dorothy act independently of corporate worship in 1802 and 1805, their habits—in sympathy with Taylor’s teaching—reveal a craving for the kinds of structures William later celebrated in Ecclesiastical Sonnets. Consequently, the apparent disparity between the high-Romantic poet of Dove Cottage and the high-Anglican Tractarian sympathizer of Rydal Mount is shown to be less severe than is often assumed. -

Thesis Spring 2015 !2

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Alice in Wonderland: Dorothy Wordsworth’s Search for Poetic! Identity in Wordsworthian Nature ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Maymay Liu Advised by Susan Meyer and Dan Chiasson, Department of English Wellesley College English Honors Thesis Spring 2015 !2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Daydream in Gold 14 William and Dorothy Wordsworth as Divergent Speakers Chapter 2: Caged Birds 35 William Wordsworth’s Poetic Treatment of Women in Nature Chapter 3: Through the Looking Glass 57 Dorothy Wordsworth’s Conception of Passivity toward Mother Nature Works Cited 82 !3 Acknowledgements! I am deeply grateful to Professor Susan Meyer and Professor Dan Chiasson for acting as my thesis advisors, both of whom were gracious enough to take on my project without being familiar with Dorothy Wordsworth beforehand. I would never have produced more than a page of inspired writing about Dorothy without their guidance and support. I thank Professor Alison Hickey, who first introduced me to Dorothy and William as a junior (I took her class “Romantic Poetry” in the fall, and promptly came back for more with “Sister and Brother Romantics” in the spring). Despite being on sabbatical for the academic year, she has provided encouragement, advice and copious amounts of hot tea when the going got tough. I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee, Professor Yoon Sun Lee, Professor Gurminder Bhogal, Professor Octavio Gonzalez, Professor Joseph Joyce, and Professor Margery Sabin for their time and fresh insights. I thank the Wellesley College Committee on Curriculum and Academic Policy for awarding me a Jerome A. Schiff Fellowship in support of my thesis. -

English Language and Literature in Borrowdale

English Language and Literature Derwentwater Independent Hostel is located in the Borrowdale Valley, 3 miles south of Keswick. The hostel occupies Barrow House, a Georgian mansion that was built for Joseph Pocklington in 1787. There are interesting references to Pocklington, Barrow House, and Borrowdale by Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey. Borrowdale and Keswick have been home to Coleridge, Southey and Walpole. Writer Born Selected work Places to visit John Dalton 1709 Poetry Whitehaven, Borrowdale William Wordsworth 1770 Poetry: The Prelude Cockermouth (National Trust), Dove Cottage (Wordsworth Trust) in Grasmere, Rydal Mount, Allan Bank (National Trust) in Grasmere Dorothy Wordsworth 1771 Letters and diaries Cockermouth (National Trust), Dove Cottage (Wordsworth Trust), Rydal Mount, Grasmere Samuel Taylor Coleridge 1772 Poetry Dove Cottage, Greta Hall (Keswick), Allan Bank Robert Southey 1774 Poetry: The Cataract of Lodore Falls and the Bowder Stone (Borrowdale), Dove Lodore Cottage, Greta Hall, grave at Crosthwaite Church Thomas de Quincey 1785 Essays Dove Cottage John Ruskin 1819 Essays, poetry Brantwood (Coniston) Beatrix Potter 1866 The Tale of Squirrel Lingholm (Derwent Water), St Herbert’s Island (Owl Island Nutkin (based on in the Tale of Squirrel Nutkin), Hawkshead, Hill Top Derwent Water) (National Trust), Armitt Library in Ambleside Hugh Walpole 1884 The Herries Chronicle Watendlath (home of fictional character Judith Paris), (set in Borrowdale) Brackenburn House on road beneath Cat Bells (private house with memorial plaque on wall), grave in St John’s Church in Keswick Arthur Ransome 1884 Swallows and Amazons Coniston and Windermere Norman Nicholson 1914 Poetry Millom, west Cumbria Hunter Davies 1936 Journalist, broadcaster, biographer of Wordsworth Margaret Forster 1938 Novelist Carlisle (Forster’s birthplace) Melvyn Bragg 1939 Grace & Mary (novel), Words by the Water Festival (March) Maid of Buttermere (play) Resources and places to visit 1. -

Dove Cottage Was the Home to Which, from 1799 to 1808, He Returned from His Walks, the Nurturing Cell in Which Many of His Best Poems Were Grown

Dove Cottage was the home to which, from 1799 to 1808, he returned from his walks, the nurturing cell in which many of his best poems were grown. His poetical career was long, lasting until 1850, and the muse gleamed only fitfully in the last decades. He had become a national poet, like Tennyson; the productivity was there, but not the light. By contrast, in Dove Cottage he wrote this: My heart leaps up when I behold A rainbow in the sky: So was it when my life began; So is it now I am a man; So be it when I shall grow old, Or let me die! And these lines, almost too well-known, on his sighting of wild daffodils in Ullswater: Continuous as the stars that shine And twinkle on the milky way They stretched in never-ending line Along the margin of a bay; Ten thousand saw I at a glance, Tossing their heads in sprightly dance. And these, perhaps his greatest, from the “Immortality” ode: Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, Hath had elsewhere its setting, And cometh from afar; Not in entire forgetfulness, And not in utter nakedness, From God, who is our home. The blaze of inspiration in these poems—the sense of each object “apparell’d in celestial light”—is all the more striking because Dove Cottage is a dark, poky place. The steep slopes of Rydal Fell and Nab Scar crowd in this tiny, limewashed house to north, south and east; only to the south-west does the view open up to Grasmere Lake and the facing mountains, chased by shifting colours and shadows of the clouds, as Dorothy, Wordsworth’s sister, often described them. -

Leeches and Opium: De Quincey Replies to "Resolution And

Leeches and Opium: De Quincey Replies to "Resolution and Independence" in "Confessions of an English Opium-Eater" Author(s): Julian North Source: The Modern Language Review, Vol. 89, No. 3 (Jul., 1994), pp. 572-580 Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3735116 Accessed: 18/03/2009 11:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mhra. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Modern Humanities Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Modern Language Review. -

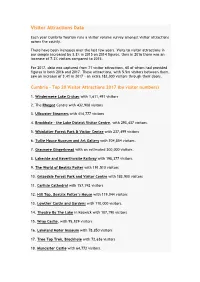

Visitor Attractions Data

Visitor Attractions Data Each year Cumbria Tourism runs a visitor volume survey amongst visitor attractions across the county. There have been increases over the last few years. Visits to visitor attractions in our sample increased by 3.3% in 2015 on 2014 figures, then in 2016 there was an increase of 7.2% visitors compared to 2015. For 2017, data was captured from 71 visitor attractions, 60 of whom had provided figures in both 2016 and 2017. These attractions, with 5.5m visitors between them, saw an increase of 3.4% in 2017 - an extra 182,000 visitors through their doors. Cumbria - Top 20 Visitor Attractions 2017 (by visitor numbers) 1. Windermere Lake Cruises with 1,611,491 visitors 2. The Rheged Centre with 432,908 visitors 3. Ullswater Steamers with 414,777 visitors 4. Brockhole – the Lake District Visitor Centre, with 293,437 visitors. 5. Whinlatter Forest Park & Visitor Centre with 237,499 visitors 6. Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery with 204,854 visitors. 7. Grasmere Gingerbread with an estimated 200,000 visitors. 8. Lakeside and Haverthwaite Railway with 198,377 visitors. 9. The World of Beatrix Potter with 191,510 visitors 10. Grizedale Forest Park and Visitor Centre with 183,900 visitors 11. Carlisle Cathedral with 157,742 visitors 12. Hill Top, Beatrix Potter’s House with 119,044 visitors 13. Lowther Castle and Gardens with 110,000 visitors. 14. Theatre By The Lake in Keswick with 107,790 visitors 15. Wray Castle, with 95,829 visitors 16. Lakeland Motor Museum with 78,850 visitors 17. Tree Top Trek, Brockhole with 72,636 visitors 18. -

Dove Cottage October 2019 – March 2020

What’s On Dove Cottage October 2019 – March 2020 Peter De Wint (1784-1849), Distant View of Lowther Castle, c.1821-35 1 ‘What pensive beauty autumn shows, Before she hears the sound Of winter rushing in, to close The emblematic round!’ From ‘Thoughts on the Seasons’ by William Wordsworth 3 Talks 5 Workshops 7 Discovering the Lake District 200 Years Ago 9 Wintertide Reflections 11 Literature Classes 13 Poetry Party for National Poetry Day 14 The Poetry Business 15 Family Fun Activities 16 Regular Gatherings 17 Essentials 18 Diary wordsworth.org.uk 2 WELCOME ‘This programme takes us into the year of Wordsworth’s 250th birthday’ Welcome to the programme for 2019-20. Topics include health issues that affected the For the first time, we shall enjoy events in Wordsworth family, the women of the local our new Café and Learning Space which linen industry, a radical look at Mary Shelley’s are part of the Reimagining Wordsworth novel Frankenstein, and an afternoon redevelopment project here in Grasmere. enjoying books, manuscripts and pictures relating to the discovery of the Lake District Join us for seasonal refreshments in the 200 years ago. Pamela Woof will deliver Café and informal talks led by our staff and her fourth and final season of workshops trainees, each on a different topic connected studying Wordsworth’s greatest poem, to the Wordsworths: food, ferries, the The Prelude. Grasmere History Group will French Revolution, bookbinding and more. continue to meet monthly here too. The Learning Space will host two workshops on hedgerow herbs and yuletide traditions We will soon be announcing the three (Lesley Hoyle), as well as printmaking (Kim poets who will be joining us for month-long Tillyer) and family yoga (Lakes Yoga).