The Danubian Lands Between the Black, Aegean and Adriatic Seas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı

T.C. TARSUS ÜNİVERSİTESİ REKTÖRLÜĞÜ Genel Sekreterlik Sayı : E-66676008-051.01-84 02.03.2021 Konu : Kongre Duyurusu DAĞITIM Üniversitemiz Uygulamalı Bilimler Fakültesi ev sahipliğinde, Mersin Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi, Osmaniye Korkut Ata Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi ve Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi işbirliği ile ortaklaşa düzenlenen 08-09 Ekim 2021 tarihleri arasında çevrimiçi olarak gerçekleştirilecek olan “ Uluslararası Dijital İşletme, Yönetim ve İktisat Kongresi (International Digital Business, Management And Economics Congress)’ne ilişkin afiş görseli ekte gönderilmekte olup kongre hakkındaki detaylı bilgilere icdbme2021.tarsus.edu.tr adresinden ulaşılabilecektir. Söz konusu kongrenin kurumunuz ilgili birimlerine ve akademik personeline duyurulması hususunda ; Bilgilerinizi ve gereğini arz ederim. Prof. Dr. Orhan AYDIN Rektör Ek : Afiş (2 Sayfa) Dağıtım : Abdullah Gül Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Acıbadem Mehmet Ali Aydınlar Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adana Alparslan Türkeş Bilim ve Teknoloji Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Adıyaman Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Akdeniz Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Aksaray Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Alanya Hamdullah Emin Paşa Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Amasya Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anadolu Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Anka Teknoloji Üniversitesi Rektörlüğü Ankara -

Poetry South

Poetry South Issue 11 2019 Poetry South Editor Kendall Dunkelberg Contributing & Angela Ball, University of Southern Mississippi Advisory Editors Carolyn Elkins, Tar River Poetry Ted Haddin, University of Alabama at Birmingham John Zheng, Mississippi Valley State University Assistant Editors Diane Finlayson Elizabeth Hines Dani Putney Lauren Rhoades Tammie Rice Poetry South is a national journal of poetry published annually by Mississippi University for Women (formerly published by Yazoo River Press). The views expressed herein, except for editorials, are those of the writers, not the editors or Mississippi University for Women. Poetry South considers submissions year round. Submissions received after the deadline of July 15 will be considered for the following year. No previously published material will be accepted. Poetry South is not responsible for unsolicited submissions and their loss. Submissions are accepted through Submittable: https://poetrysouth.submittable.com/ Subscription rates are $10 for one year, $18 for two years; the foreign rate is $15 for one year, $30 for two years. All rights revert to the authors after publication. We request Poetry South be credited with initial publication. Queries or other correspondence may be emailed to: [email protected]. Queries and subscriptions sent by mail should be addressed to: Poetry South, MFA Creative Writing, 1100 College St., W-1634, Columbus MS 39701. ISSN 1947-4075 (Print) ISSN 2476-0749 (Online) Copyright © 2019 Mississippi University for Women Indexed by EBSCOHost/Literary -

Stable Lead Isotope Studies of Black Sea Anatolian Ore Sources and Related Bronze Age and Phrygian Artefacts from Nearby Archaeological Sites

Archaeometry 43, 1 (2001) 77±115. Printed in Great Britain STABLE LEAD ISOTOPE STUDIES OF BLACK SEA ANATOLIAN ORE SOURCES AND RELATED BRONZE AGE AND PHRYGIAN ARTEFACTS FROM NEARBY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES. APPENDIX: NEW CENTRAL TAURUS ORE DATA E. V. SAYRE, E. C. JOEL, M. J. BLACKMAN, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA K. A. YENER Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1155 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA and H. OÈ ZBAL Faculty of Arts and Sciences, BogÆazicËi University, Istanbul, Turkey The accumulated published database of stable lead isotope analyses of ore and slag specimens taken from Anatolian mining sites that parallel the Black Sea coast has been augmented with 22 additional analyses of such specimens carried out at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Multivariate statistical analysis has been used to divide this composite database into ®ve separate ore source groups. Evidence that most of these ore sources were exploited for the production of metal artefacts during the Bronze Age and Phrygian Period has been obtained by statistically comparing to them the isotope ratios of 184 analysed artefacts from nine archaeological sites situated within a few hundred kilometres of these mining sites. Also, Appendix B contains 36 new isotope analyses of ore specimens from Central Taurus mining sites that are compatible with and augment the four Central Taurus Ore Source Groups de®ned in Yener et al. (1991). KEYWORDS: BLACK SEA, CENTRAL TAURUS, ANATOLIA, METAL, ORES, ARTEFACTS, BRONZE AGE, MULTIVARIATE, STATISTICS, PROBABILITIES INTRODUCTION This is the third in a series of papers in which we have endeavoured to evaluate the present state of the application of stable lead isotope analyses of specimens from metallic ore sources and of ancient artefacts from Near Eastern sites to the inference of the probable origins of such artefacts. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi * Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

KARADENİZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ * SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI ANTİK ÇAĞDA HERMONASSA LİMANI: SİYASİ VE EKONOMİK GELİŞMELER YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Betül AKKAYA MAYIS-2018 TRABZON KARADENİZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ * SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI ANTİK ÇAĞDA HERMONASSA LİMANI: SİYASİ VE EKONOMİK GELİŞMELER YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Betül AKKAYA Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Osman EMİR MAYIS-2018 TRABZON ONAY Betül AKKAYA tarafından hazırlanan Antik Çağda Hermonassa Limanı: Siyasi ve Ekonomik Gelişmeler adlı bu çalışma 17.10.2018 tarihinde yapılan savunma sınavı sonucunda oy birliği/ oy çokluğu ile başarılı bulunarak jürimiz tarafından Tarih Anabilim Dalında Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. Juri Üyesi Karar İmza Unvanı- Adı ve Soyadı Görevi Kabul Ret Prof. Dr. Mehmet COĞ Başkan Prof. Dr. Süleyman ÇİĞDEM Üye Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Osman EMİR Üye Yukarıdaki imzaların, adı geçen öğretim üyelerine ait olduklarını onaylarım. Prof. Dr. Yusuf SÜRMEN Enstitü Müdürü BİLDİRİM Tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu, ayrıca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada orijinal olmayan her türlü kaynağa eksiksiz atıf yapıldığını, aksinin ortaya çıkması durumunda her tür yasal sonucu kabul ettiğimi beyan ediyorum. Betül AKKAYA 21.05.2018 ÖNSÖZ Kolonizasyon kelime anlamı olarak bir ülkenin başka bir ülke üzerinde ekonomik olarak egemenlik kurması anlamına gelmektedir. Koloni ise egemenlik kurulan toprakları ifade etmektedir. Antik çağlardan itibaren kolonizasyon hareketleri devam etmektedir. Greklerin Karadeniz üzerinde gerçekleştirdiği koloni faaliyetleri ışığında ele alınan Hermonassa antik kenti de Kuzey Karadeniz kıyılarında yer alan önemli bir Grek kolonisidir. Bugünkü Kırım sınırları içinde yer almış olan kent aynı zamanda Bosporus Krallığı içerisinde önemli bir merkez olarak var olmuştur. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

El Spill De Jaume Roig. Estudio De Relaciones Semióticas Con La Picaresca

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 El Spill de Jaume Roig. Estudio de relaciones semióticas con la picaresca Raul Macias Cotano The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1913 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EL SPILL DE JAUME ROIG. ESTUDIO DE RELACIONES SEMIÓTICAS CON LA PICARESCA por RAÚL MACÍAS COTANO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in the program of Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Literatures and Languages, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 RAÚL MACÍAS COTANO All Rights Reserved ii El SPILL DE JAUME ROIG. ESTUDIO DE RELACIONES SEMIÓTICAS CON LA PICARESCA by Raúl Macías Cotano This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in of Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Literatures and Languages in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Lía Schwartz Date Chair of Examining Committee José del Valle Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: John O’Neill Nuria Morgado THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EL SPILL DE JAUME ROIG. ESTUDIO DE RELACIONES SEMIÓTICAS CON LA PICARESCA by Raúl Macías Cotano Advisor: Prof. Lía Schwartz The Spill is a literary work written in the Catalan dialect of Valencia in 1460 by Jaume Roig, a prestigious doctor whose personal and public life is well known. -

UC Classics Library New Acquisitions February 2019 1

UC Classics Library New Acquisitions February 2019 1. Res publica litterarum. Lawrence, Kan., University of Kansas. S. Prete, 2083 Wescoe Hall, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 66045. LOCATION = CLASS Journals. AS30 .R47 v.39(2016). 2. Philosophenwege / Wolfram Hoepfner. Konstanz : UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, [2018]. Xenia (Konstanz, Germany) ; Heft 52. LOCATION = CLASS Oversize. B173 .H647 2018. 3. Speeches for the dead : essays on Plato's Menexenus / edited by Harold Parker and Jan Maximilian Robitzsch. Berlin ; Boston : De Gruyter, [2018]. Beiträge zur Altertumskunde ; 368. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B376.M46 P37 2018. 4. Metafisica e scienza negli antichi e nei moderni / a cura di Elisabetta Cattanei e Laura Stochino. Lecce : Milella, [2017]. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B485 .M375 2017. 5. Dynamis : sens et genèse de la notion aristotélicienne de puissance / par David Lefebvre. Paris : Librairie philosophique J. Vrin, 2018. Bibliothèque d'histoire de la philosophie. Nouvelle série. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B491.P66 L44 2018. 6. La vertu en acte chez Aristote : une sagesse propre à la vie heureuse / Gilles Guigues. Paris : L'Harmattan, [2016]. Collection L'ouverture philosophique. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B491.V57 G84 2016. 7. Politics and philosophy at Rome : collected papers / Miriam T. Griffin ; edited by Catalina Balmaceda. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2018. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B505 .G75 2018. 8. Apprendre à penser avec Marc Aurèle / Robert Tirvaudey. Paris : L'Harmattan, [2017]. Collection L'ouverture philosophique. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. B583 .T57 2017. 9. Les principes cosmologiques du platonisme : origines, influences et systématisation / études réunies et éditées par Marc-Antoine Gavray et Alexandra Michalewski. Turnhout, Belgium : Brepols, [2017]. Monothéismes et philosophie. LOCATION = CLASS Stacks. -

Bosporos Studies 2001 2002 2003

BOSPOROS STUDIES 2001 Vol. I Vinokurov N.I. Acclimatization of vine and the initial period of the viticulture development in the Northern Black Sea Coast Gavrilov A. V, Kramarovsky M.G. The barrow near the village of Krinichky in the South-Eastern Crimea Petrova E.B. Menestratos and Sog (on the problem of King's official in Theodosia in the first centuries AD) Fedoseyev N.F. On the collection of ceramics stamps in Warsaw National Museum Maslennikov A.A. Rural settlements of European Bosporos (Some problems and results of research) Matkovskaya T.A. Men's costume of European Bosporos of the first centuries AD (materials of Kerch lapidarium) Sidorenko V.A. The highest military positions in Bosporos in the 2nd – the beginning of the 4th centuries (on the materials of epigraphies) Zin’ko V.N., Ponomarev L.Yu. Research of early medieval monuments in the neighborhood of Geroevskoye settlement Fleorov V.S. Burnished bowls, dishes, chalices and kubyshki of Khazar Kaghanate Gavrilov A.V. New finds of antique coins in the South-Eastern Crimea Zin’ko V.N. Bosporos City of Nymphaion and the Barbarians Illarioshkina E.N. Gods and heroes of Greek myths in Bosporos gypsum plastics Kulikov A.V. On the problem of the crisis of money circulation in Bosporos in the 3rd century ВС Petrova E.B. On cults of ancient Theodosia Ponomarev D.Yu. Paleopathogeography of kidney stone illness in the Crimea in ancient and Medieval epoch Magomedov B. Cherniakhovskaya culture and Bosporos Niezabitowska V. Collection of things from Kerch and Caucasus in Wroclaw Archaeology Museum 2002 Vol. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

Arrian's Voyage Round the Euxine

— T.('vn.l,r fuipf ARRIAN'S VOYAGE ROUND THE EUXINE SEA TRANSLATED $ AND ACCOMPANIED WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL DISSERTATION, AND MAPS. TO WHICH ARE ADDED THREE DISCOURSES, Euxine Sea. I. On the Trade to the Eqft Indies by means of the failed II. On the Di/lance which the Ships ofAntiquity ufually in twenty-four Hours. TIL On the Meafure of the Olympic Stadium. OXFORD: DAVIES SOLD BY J. COOKE; AND BY MESSRS. CADELL AND r STRAND, LONDON. 1805. S.. Collingwood, Printer, Oxford, TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR ADRIAN AUGUSTUS, ARRIAN WISHETH HEALTH AND PROSPERITY. We came in the courfe of our voyage to Trapezus, a Greek city in a maritime fituation, a colony from Sinope, as we are in- formed by Xenophon, the celebrated Hiftorian. We furveyed the Euxine fea with the greater pleafure, as we viewed it from the lame fpot, whence both Xenophon and Yourfelf had formerly ob- ferved it. Two altars of rough Hone are ftill landing there ; but, from the coarfenefs of the materials, the letters infcribed upon them are indiftincliy engraven, and the Infcription itfelf is incor- rectly written, as is common among barbarous people. I deter- mined therefore to erect altars of marble, and to engrave the In- fcription in well marked and diftinct characters. Your Statue, which Hands there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and of the defign, as it reprefents You pointing towards the fea; but it bears no refemblance to the Original, and the execution is in other re- fpects but indifferent. Send therefore a Statue worthy to be called Yours, and of a fimilar delign to the one which is there at prefent, b as 2 ARYAN'S PERIPLUS as the fituation is well calculated for perpetuating, by thefe means, the memory of any illuftrious perfon. -

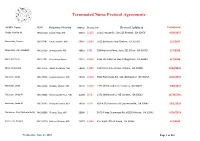

Terminated Nurse Protocol Agreements

Terminated Nurse Protocol Agreements APRN Name RN# Delgating Physicia PHY# Protocol # Protcol Address Terminated Abebe, Mahlet M. RN221110 Jayesh Naik, MD 33253 20253 11111 Houze Rd., Ste 225 Roswell, GA 30076 4/18/2017 Abernathy, Pamela RN107241 Dark, Jennifer MD 66016 10682 1012 Burleyson Road Dalton, GA 30710 2/1/2017 Abernathy, Kari Elizabeth RN154956 Jaime Burkle, MD 48881 9783 309 Highland Pkwy, Suite 201 Ellijay, GA 30539 5/7/2012 Abiri, Autherine RN212591 Felix Amoa-Bonsu 55916 20369 5185 Old National Hwy College Park, GA 30349 6/7/2018 Abon, Moradeke RN141176 Albert Anderson, MD 58136 11082 341 Ponce deLeon Ave. Atlanta, GA 30308 8/24/2015 Abraham, Linda RN178502 Lynette Stewart, MD 39681 11113 3660 Flat Shoals Rd., Ste 180 Decatur, GA 30034 4/16/2013 Abraham, Linda RN178502 Hodges, Sharon MD 40759 10470 1372 Wellbrook Circle Conyers, GA 30012 3/30/2012 Abraham, Linda M. RN178502 Mohamad El-Attar, MD 41286 9546 1372 Wellbrook Cir NE Conyers, GA 30012 11/30/2011 Abraham, Linda M. RN178502 Phillip Bannister, MD 16503 5019 603-A Old Norcross Rd Lawrenceville, GA 30045 10/1/2010 Abramson, Cara Michelle Rothf RN108696 Thomas Seay, MD 30884 5 5670 P'tree Dunwoody Rd, #1100 Atlanta, GA 30342 6/16/2014 Acree, Lisa Pinkard RN126710 Melissa Dillmon, MD 54073 12389 255 West Fifth St Rome, GA 30165 4/1/2015 Wednesday, June 27, 2018 Page 1 of 410 APRN Name RN# Delgating Physicia PHY# Protocol # Protcol Address Terminated Acree, Lisa Pinkard RN126710 William Whaley, MD 11504 9 750 Deep South Farm Rd Blairsville, GA 30512 9/25/2014 Acree, Lisa RN126710 McCormick 25219 16688 501 Redmond Rd Rome, GA 30165 12/11/2015 Adams, Mary Allison RN191947 Brandon K.