The Rule of Law Implies Legal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the CARIBBEAN COURT of JUSTICE Appellate Jurisdiction on APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL of BELIZE CCJ

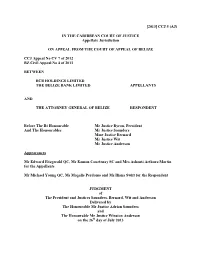

[2013] CCJ 5 (AJ) IN THE CARIBBEAN COURT OF JUSTICE Appellate Jurisdiction ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL OF BELIZE CCJ Appeal No CV 7 of 2012 BZ Civil Appeal No 4 of 2011 BETWEEN BCB HOLDINGS LIMITED THE BELIZE BANK LIMITED APPELLANTS AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BELIZE RESPONDENT Before The Rt Honourable Mr Justice Byron, President And The Honourables Mr Justice Saunders Mme Justice Bernard Mr Justice Wit Mr Justice Anderson Appearances Mr Edward Fitzgerald QC, Mr Eamon Courtenay SC and Mrs Ashanti Arthurs-Martin for the Appellants Mr Michael Young QC, Ms Magalie Perdomo and Ms Iliana Swift for the Respondent JUDGMENT of The President and Justices Saunders, Bernard, Wit and Anderson Delivered by The Honourable Mr Justice Adrian Saunders and The Honourable Mr Justice Winston Anderson on the 26th day of July 2013 JUDGMENT OF THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE SAUNDERS [1] The London Court of International Arbitration (“the Tribunal”) determined that the State of Belize should pay damages for dishonouring certain promises it had made to two commercial companies, namely, BCB Holdings Limited and The Belize Bank Limited (“the Companies”). The promises were contained in a Settlement Deed as Amended (“the Deed”) executed in March 2005. The Deed provided that the Companies should enjoy, from the 1st day of April, 2005, a tax regime specially crafted for them and at variance with the tax laws of Belize. [2] This unique regime was never legislated but it was honoured by the State for two years until it was repudiated in 2008 after a change of administration in Belize following a General Election. -

United States Canada

Comparative Table of the Supreme Courts of the United States and Canada United States Canada Foundations Model State judiciaries vs. independent and Unitary model (single hierarchy) where parallel federal judiciary provinces appoint the lowest court in the province and the federal government appoints judges to all higher courts “The judicial Power of the United “Parliament of Canada may … provide for the States, shall be vested in one Constitution, Maintenance, and Organization of Constitutional supreme Court” Constitution of the a General Court of Appeal for Canada” Authority United States, Art. III, s. 1 Constitution Act, 1867, ss. 101 mandatory: “the judicial Power of optional: “Parliament of Canada may … provide the United States, shall be vested in for … a General Court of Appeal for Canada” (CA Creation and one supreme Court” Art III. s. 1 1867, s. 101; first Supreme Court Act in 1875, Retention of the (inferior courts are discretionary) after debate; not constitutionally entrenched by Supreme Court quasi-constitutional convention constitutionally entrenched Previous higher appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy judicial Council were abolished in 1949 authority Enabling Judiciary Act Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26 Legislation “all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising “a General Court of Appeal for Canada” confers under this Constitution” Art III, s. 2 plenary and ultimate authority “the Laws of the United States and Treaties made … under their Authority” Art III, s. 2 “Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls” (orig. jur.) Jurisdiction of Art III, s. 2 Supreme Court “all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction” Art III, s. -

Newton Spence and Peter Hughes V the Queen

SAINT VINCENT & THE GRENADINES IN THE COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 20 OF 1998 BETWEEN: NEWTON SPENCE Appellant and THE QUEEN Respondent and SAINT LUCIA IN THE COURT OF APPEAL CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 14 OF 1997 BETWEEN: PETER HUGHES Appellant and THE QUEEN Respondent Before: The Hon. Sir Dennis Byron Chief Justice The Hon. Mr. Albert Redhead Justice of Appeal The Hon. Mr. Adrian Saunders Justice of Appeal (Ag.) Appearances: Mr. J. Guthrie QC, Mr. K. Starmer and Ms. N. Sylvester for the Appellant Spence Mr. E. Fitzgerald QC and Mr. M. Foster for the Appellant Hughes Mr. A. Astaphan SC, Ms. L. Blenman, Solicitor General, Mr. James Dingemans, Mr. P. Thompson, Mr. D. Browne, Solicitor General, Dr. H. Browne and Ms. S. Bollers for the Respondents -------------------------------------------- 2000: December 7, 8; 2001: April 2. -------------------------------------------- JUDGMENT [1] BYRON, C.J.: This is a consolidated appeal, which concerns two appellants convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Saint Vincent and Saint Lucia respectively who exhausted their appeals against conviction and raised constitutional arguments against the mandatory sentence of death before the Privy Council which had not previously been raised in the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal. Background [2] The Privy Council granted leave to both appellants to appeal against sentence and remitted the matter to the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal to consider and determine whether (a) the mandatory sentence of death imposed should be quashed (and if so what sentence (including the sentence of death) should be imposed), or (b) the mandatory sentence of death imposed ought to be affirmed. -

The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges Under Commonwealth

The The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges under Commonwealth Principles Appoin An independent, impartial and competent judiciary is essential to the rule tmen of law. This study considers the legal frameworks used to achieve this and examines trends in the 53 member states of the Commonwealth. It asks: t, Te ! who should appoint judges and by what process? nur The Appointment, Tenure ! what should be the duration of judicial tenure and how should judges’ remuneration be determined? e and and Removal of Judges ! what grounds justify the removal of a judge and who should carry out the necessary investigation and inquiries? Re mo under Commonwealth The study notes the increasing use of independent judicial appointment va commissions; the preference for permanent rather than fixed-term judicial l of Principles appointments; the fuller articulation of procedural safeguards necessary Judge to inquiries into judicial misconduct; and many other developments with implications for strengthening the rule of law. s A Compendium and Analysis under These findings form the basis for recommendations on best practice in giving effect to the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles (2003), the leading of Best Practice Commonwealth statement on the responsibilities and interactions of the three Co mmon main branches of government. we This research was commissioned by the Commonwealth Secretariat, and undertaken and alth produced independently by the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The Centre is part of the British Institute of International and -

Paying Homage to the Right Honourable Sir C.M. Dennis Byron Meet the Team Chief Editor CAJO Executive Members the Honourable Mr

NewsJuly 2018 Issue 8 Click here to listen to the theme song of Black Orpheus as arranged by Mr. Neville Jules and played by the Massy Trinidad All Stars Steel Orchestra. Paying Homage to The Right Honourable Sir C.M. Dennis Byron Meet the Team Chief Editor CAJO Executive Members The Honourable Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders Chairman Contributors Mr. Terence V. Byron, C.M.G. The Honourable Justice Mr. Adrian Saunders Madam Justice Indra Hariprashad-Charles Caribbean Court of Justice Retired Justice of Appeal Mr. Albert Redhead Mr. Justice Constant K. Hometowu Vice Chairman Mr. Justice Vagn Joensen Justice of Appeal Mr. Peter Jamadar Trinidad and Tobago Graphic Artwork & Layout Ms. Danielle M Conney Sir Marston Gibson, Chief Justice - Barbados Country Representativesc Chancellor Yonnette Cummings-Edwards - Guyana Mr. Justice Mauritz de Kort, Vice President of the Joint Justice Ian Winder - The Bahamas Court of The Dutch Antilles Registrar Shade Subair Williams - Bermuda; Madam Justice Sandra Nanhoe - Suriname Mrs. Suzanne Bothwell, Court Administrator – Cayman Madam Justice Nicole Simmons - Jamaica Islands Madam Justice Sonya Young – Belize Madam Justice Avason Quinlan-Williams - Trinidad and Tobago c/o Caribbean Court of Justice Master Agnes Actie - ECSC 134The CaribbeanHenry Street, Association of Judicial Of�icers (CAJO) Port of Spain, Chief Magistrate Christopher Birch – Barbados Trinidad & Tobago Senior Magistrate Patricia Arana - Belize Registrar Musa Ali - Caribbean Competition Commit- 623-2225 ext 3234 tee - Suriname [email protected] In This Issue Editor’s Notes Pages 3 - 4 Excerpts of the Family Story Pages 5 - 7 The Different Sides of Sir Dennis Pages 8 - 9 My Tribute to the Rt. -

Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments Through 2016

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 constituteproject.org Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments through 2016 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE STATE AND THE CONSTITUTION . 7 1. The State . 7 2. Constitution is supreme law . 7 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF THE INDIVIDUAL . 7 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual . 7 4. Protection of right to life . 7 5. Protection of right to personal liberty . 8 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour . 10 7. Protection from inhuman treatment . 11 8. Protection from deprivation of property . 11 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property . 14 10. Provisions to secure protection of law . 15 11. Protection of freedom of conscience . 17 12. Protection of freedom of expression . 17 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association . 18 14. Protection of freedom to establish schools . 18 15. Protection of freedom of movement . 19 16. Protection from discrimination . 20 17. Enforcement of protective provisions . 21 17A. Payment or retiring allowances to Members . 22 18. Derogations from fundamental rights and freedoms under emergency powers . 22 19. Interpretation and savings . 23 CHAPTER III: CITIZENSHIP . 25 20. Persons who became citizens on 12 March 1968 . 25 21. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens . 25 22. Persons born in Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . 26 23. Persons born outside Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . -

Supreme Court Act 1905

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA SUPREME COURT ACT 1905 1905 : 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY 1 Interpretation CONSTITUTION OF THE SUPREME COURT 2 Union of existing Courts into Supreme Court 3 Prescription of number of Puisne Judges 4 Assistant Justices 5 Appointment of Judges of Supreme Court 6 Precedence of Judges 7 Powers of Judges to exercise jurisdiction 8 Powers of Acting Chief Justices 9 Powers etc. of Puisne Judge 10 Seal of Court 11 Place of sitting JURISDICTION AND LAW 12 Jurisdiction of Supreme Court 13 [repealed] 14 Jurisdiction in respect of persons suffering from mental disorder 15 Extent of application of English law 16 [repealed] 17 [repealed] 18 Concurrent administration of law and equity 19 Rules of law upon certain points 20 Proceedings in chambers 21 Provision as to criminal procedure 22 Savings for rules of evidence and law relating to jurors, etc. 1 SUPREME COURT ACT 1905 23 Restriction on institution of vexatious actions ADMIRALTY JURISDICTION 24 Admiralty jurisdiction of the Court 25 Mode of exercise of Admiralty jurisdiction 26 Jurisdiction in personam in collision and other similar cases 27 Wages 28 Supreme Court not to have jurisdiction in cases falling within Rhine Convention 29 Savings DISPOSAL OF MONEY PAID INTO COURT 30 Disposal of money paid into court 31 Payment into Consolidated Fund 32 Money paid into court prior to 1 July 1980 and still in court on that date 33 Notice of payment into court 34 Forfeiture of money 35 Rules relating to the payment of interest on money paid into court SITTINGS AND DISTRIBUTION OF BUSINESS OF THE COURT 36 Sittings of the Court 37 Session day 46 [] OFFICERS OF THE COURT 47 Duties of Provost Marshal General 48 Registrar and Assistant Registrar of the Court 49 Duties of Registrar 50 Taxing Master BARRISTERS AND ATTORNEYS 51 Admission of barristers and attorneys 52 Deposit of certificate of call etc. -

The Gender Equality Issue CAJO NEWS Team

NOVEMBER 2016 • ISSUE 6 The Gender Equality Issue CAJO NEWS Team CHIEF EDITOR CAJO BOARD MEMBERS The Hon. Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders Mr. Justice Adrian Saunders (Chairman) Justice Charmaine Pemberton (Deputy Chairman) Chief Justice Yonette Cummings Chief Justice Evert Jan van der Poel CONTRIBUTORS Justice Christopher Blackman Justice Charles-Etta Simmons Justice Francis Belle Chief Magistrate Ann Marie Smith Justice Sandra Nanhoe-Gangadin Senior Magistrate Patricia Arana Justice Nicole Simmons Justice Sonya Young Parish Judge Simone Wolfe-Reece Magistrate Lisa Ramsumair-Hinds Registrar Barbara Cooke-Alleyne GRAPHIC ARTWORK, LAYOUT Registrar Camille Darville-Gomez Ms. Seanna Annisette The Caribbean Association of Judicial Ocers (CAJO) c/o Caribbean Court of Justice 134 Henry Street Port of Spain Trinidad and Tobago Tel: (868) 623-2225 ext. 3234 Email: [email protected] IN EDITOR’s THIS Notes ISSUE P.3- P.4 CAJO PROFILE By the time some of you read this edition of CAJO NEWS the Referendum results in Grenada SCAJOue. would have been known. This is assuming of course that the Referendum does take place on The Hon. Mr Justice November 24th as scheduled at the time of writing. The vote had earlier been slated for 27th Rolston Nelson October. This exercise in Constitution re-making holds huge implications not just for the people of Grenada, Carriacou and Petit Martinique but for the entire CARICOM and English speaking Caribbean. In this edition CAJO NEWS lists the choices before the people of our sister isles. In this issue, CAJO NEWS publishes an interview we conducted with Hon Mr Justice Rolston Nelson, the longest serving judge of the Caribbean Court of Justice. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3. -

Forum À L'intention Des Juges Spécialisés En Propriété

WIPO/IP/JU/GE/19/INF/1 ORIGINAL: FRANÇAIS / ENGLISH DATE: 13 NOVEMBRE / NOVEMBER 13, 2019 Forum à l’intention des juges spécialisés en propriété intellectuelle Genève, 13 – 15 novembre 2019 Intellectual Property Judges Forum Geneva, November 13 to 15, 2019 LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LIST OF PARTICIPANTS établie par le Secrétariat prepared by the Secretariat WIPO FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY WIPO/IP/JU/GE/19/INF/1 page 2 I. PARTICIPANTS (par ordre alphabétique / in alphabetical order) ABDALLA Muataz (Mr.), Judge, Intellectual Property Court, Khartoum, Sudan ACKAAH-BOAFO Kweku Tawiah (Mr.), Justice, High Court of Justice, Accra, Ghana AJOKU Patricia (Ms.), Justice, Federal High Court, Ibadan, Nigeria AL BUSAIDI Khalil (Mr.), Judge, Court of First Instance; President, General Administration for Judges, Council of Administrative Affairs for the Judiciary, Muscat, Oman AL KAMALI Mohamed Mahmoud (Mr.), Director General, Institute of Training and Judicial Studies, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates ALABDULQADER Ahmed (Mr.), Appeal Judge, Commercial Court, Dammam, Saudi Arabia ALABUDI Ahmed (Mr.), Appeal Judge, Commercial Section, Appeal Court, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ALARCON POLANCO Edynson Francisco (Sr.), Magistrado, Corte de Apelación del Distrito Nacional, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana ALEXANDROVA Iskra (Ms.), Judge, Third Department, Supreme Administrative Court, Sofia, Bulgaria ALHIDAR Ibrahim (Mr.), Judge, Commercial Court, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ALJABRI Nayef (Mr.), Counselor, Court of Appeal, Kuwait City, Kuwait ALKHALAF Mahmoud (Mr.), Judge, Court -

Lord Chief Justice Delegation of Statutory Functions

Delegation of Statutory Functions – Issue No. 2 of 2015 Lord Chief Justice – Delegation of Statutory Functions Introduction The Lord Chief Justice has a number of statutory functions, the exercise of which may be delegated to a nominated judicial office holder (as defined by section 109(4) of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (the 2005 Act). This document sets out which judicial office holder has been nominated to exercise specific delegable statutory functions. Section 109(4) of the 2005 Act defines a judicial office holder as either a senior judge or holder of an office listed in schedule 14 to that Act. A senior judge, as defined by s109(5) of the 2005 Act refers to the following: the Master of the Rolls; President of the Queen's Bench Division; President of the Family Division; Chancellor of the High Court; Senior President of Tribunals; Lord or Lady Justice of Appeal; or a puisne judge of the High Court. Only the nominated judicial office holder to whom a function is delegated may exercise it. Exercise of the delegated functions cannot be sub- delegated. The nominated judicial office holder may however seek the advice and support of others in the exercise of the delegated functions. Where delegations are referred to as being delegated prospectively1, the delegation takes effect when the substantive statutory provision enters into force. The schedule, which is Issue 2 of 2015, is correct as at 17 December 2015.2 It contains new delegations, revocation of certain delegations to a number of judges and corrections to the delegations to the President of the Queen’s Bench Division and Chancellor of the High Court. -

Cybercrime Convention Committee (T-CY)

www.coe.int/cybercrime Strasbourg, 30 November 2020 T-CY (2020)33 Cybercrime Convention Committee (T-CY) T-CY 23 23rd Plenary of the T-CY Virtual meeting, 30 November 2020 Meeting report T-CY(2020)33 23rd Plenary/Meeting report 1 Introduction The 23rd Plenary of the T-CY Committee, meeting online on 30 November 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, was chaired by Cristina SCHULMAN (Romania) and opened by Jan KLEIJSSEN (Director of Information Society and Action against Crime, DG 1, Council of Europe). More than 130 representatives of 57 Parties, Observer and Ad-hoc Observer States, as well as of international organisations and Council of Europe committees participated. The regular plenary session was followed by a meeting of the T-CY Protocol Drafting Plenary from 1 to 3 December 2020. 2 Decisions The T-CY decided: Agenda item 1: Opening of the meeting and adoption of the agenda . To adopt the agenda; Agenda item 2: Bureau elections . To thank the outgoing Bureau for its contribution to the work of the T-CY; . To elect Cristina SCHULMAN (Romania) as Chair and Pedro VERDELHO (Portugal) as Vice- chair of the T-CY. To elect as Bureau members: - Albert ANTWI-BOASIAKO (Ghana); - Miriam BAHAMONDE BLANCO (Spain); - Camila BOSCH CARTAGENA (Chile); - Vanessa EL KHOURY-MOAL (France); - Benjamin FITZPATRICK (USA); - Justin MILLAR (United Kingdom); - Gareth SANSOM (Canada); - Nathan WHITEMAN (Australia). Agenda item 3: Terms of Reference for the preparation of the 2nd Additional Protocol . To extend the Terms of reference for the negotiations to May 2021 to permit finalisation of the draft Protocol.