The Narratives of Cyberspace Law (Or, Learning from Casablanca)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF. Ksar Seghir 2500Ans D'échanges Inter-Civilisationnels En

Ksar Seghir 2500 ans d’échanges intercivilisationnels en Méditerranée • Première Edition : Institut des Etudes Hispanos-Lusophones. 2012 • Coordination éditoriale : Fatiha BENLABBAH et Abdelatif EL BOUDJAY • I.S.B.N : 978-9954-22-922-4 • Dépôt Légal: 2012 MO 1598 Tous droits réservés Sommaire SOMMAIRE • Préfaces 5 • Présentation 9 • Abdelaziz EL KHAYARI , Aomar AKERRAZ 11 Nouvelles données archéologiques sur l’occupation de la basse vallée de Ksar de la période tardo-antique au haut Moyen-âge • Tarik MOUJOUD 35 Ksar-Seghir d’après les sources médiévales d’histoire et de géographie • Patrice CRESSIER 61 Al-Qasr al-Saghîr, ville ronde • Jorge CORREIA 91 Ksar Seghir : Apports sur l’état de l’art et révisoin critique • Abdelatif ELBOUDJAY 107 La mise en valeur du site archéologique de Ksar Seghir Bilan et perspectives 155 عبد الهادي التازي • مدينة الق�رص ال�صغري من خﻻل التاريخ الدويل للمغرب Préfaces PREFACES e patrimoine archéologique marocain, outre qu’il contribue à mieux Lconnaître l’histoire de notre pays, il est aussi une source inépuisable et porteuse de richesse et un outil de développement par excellence. A travers le territoire du Maroc s’éparpillent une multitude de sites archéologiques allant du mineur au majeur. Citons entre autres les célèbres grottes préhistoriques de Casablanca, le singulier cromlech de Mzora, les villes antiques de Volubilis, de Lixus, de Banasa, de Tamuda et de Zilil, les sites archéologies médiévaux de Basra, Sijilmassa, Ghassasa, Mazemma, Aghmat, Tamdoult et Ksar Seghir objet de cet important colloque. Le site archéologique de Ksar Seghir est fameux par son évolution historique, par sa situation géographique et par son urbanisme particulier. -

The Alliance Israélite Universelle, Gender, and Jewish Education in Casablanca, Morocco 1886-1906

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 “The Community for Educational Experiments”: The Alliance Israélite Universelle, Gender, and Jewish Education in Casablanca, Morocco 1886-1906 Selene Allain-Kovacs [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Allain-Kovacs, Selene, "“The Community for Educational Experiments”: The Alliance Israélite Universelle, Gender, and Jewish Education in Casablanca, Morocco 1886-1906" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2714. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2714 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Community for Educational Experiments” The Alliance Israélite Universelle, Gender, and Jewish Education in Casablanca, Morocco 1886-1906 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History International & Global Studies by Sélène Allain-Kovacs B.A. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

Perspektiven Der Spolienforschung 2. Zentren Und Konjunkturen Der

Perspektiven der Spolienforschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD antiker Bauten, Bauteile und Skulpturen ist ein weitverbreite- tes Phänomen der Nachantike. Rom und der Maghreb liefern zahlreiche und vielfältige Beispiele für diese An- eignung materieller Hinterlassenscha en der Antike. Während sich die beiden Regionen seit dem Ausgang der Antike politisch und kulturell sehr unterschiedlich entwickeln, zeigen sie in der praktischen Umsetzung der Wiederverwendung, die zwischenzeitlich quasi- indus trielle Ausmaße annimmt, strukturell ähnliche orga nisatorische, logistische und rechtlich-lenkende Praktiken. An beiden Schauplätzen kann die Antike alternativ als eigene oder fremde Vergangenheit kon- struiert und die Praxis der Wiederverwendung utili- taristischen oder ostentativen Charakter besitzen. 40 · 40 Perspektiven der Spolien- forschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Abbildung Umschlag: Straßenkreuzung in Tripolis, Photo: Stefan Altekamp Typographisches Konzept und Einbandgestaltung: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN ---- URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:- First published Published under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC . DE. For the terms of use of the illustrations, please see the reference lists. www.edition-topoi.org INHALT , -, Einleitung — 7 Commerce de Marbre et Remploi dans les Monuments de L’Ifriqiya Médiévale — 15 Reuse and Redistribution of Latin Inscriptions on Stone in Post-Roman North-Africa — 43 Pulcherrima Spolia in the Architecture and Urban Space at Tripoli — 67 Adding a Layer. -

The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol

The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.nuhmafricanus3 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained, Vol. 3 Alternative title The history and description of Africa and of the notable things therein contained Author/Creator Leo Africanus Contributor Pory, John (tr.), Brown, Robert (ed.) Date 1896 Resource type Books Language English, Italian Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast;Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu, Southern Swahili Coast Source Northwestern University Libraries, G161 .H2 Description Written by al-Hassan ibn-Mohammed al-Wezaz al-Fasi, a Muslim, baptised as Giovanni Leone, but better known as Leo Africanus. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

December 2020 New Releases

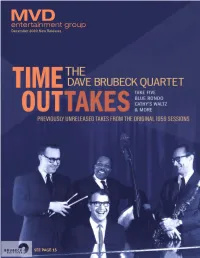

December 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 59 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 12 FEATURED RELEASES Video WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. THE DAVE BRUBECK THE RESIDENTS - 35 FEATURING MICK ROSSI - QUARTET - IN BETWEEN DREAMS: Film LIVE IN TOKYO TIME OUTTAKES LIVE IN SAN FRANCISCO Films & Docs 36 Faith & Family 56 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 57 Order Form 69 Deletions & Price Changes 65 TREMORS MANIAC A NIGHT IN CASABLANCA 800.888.0486 (2-DISC SPECIAL EDITION) 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com WALTER LURE’S L.A.M.F. BERT JANSCH - SUPERSUCKERS - FEATURING MICK ROSSI - BEST OF LIVE MOTHER FUCKERS BE TRIPPIN’ TIME OUT AND TAKE FIVE! LIVE IN TOKYO We could use a breather from what has been a most turbulent year, and with our December releases, we provide a respite with fantastic discoveries in the annals of cool jazz. THE DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET “TIME OUTTAKES” is an alternate version of the masterful TIME OUT 1959 LP, with the seven tracks heard for the first time in crisp, different versions with a bonus track and studio banter. The album’s “Take Five” is the biggest selling jazz single ever, and hearing this in different form is downright thrilling. On LP and CD. Also smooth jazz reigns supreme with a CD release of a newly discovered live performance from sax legend GEORGE COLEMAN. “IN BALTIMORE” is culled from a 1971 performance with detailed liner notes and rare photos. Kick Out the Jazz! Something else we could use is a release from oddball novelty song collector DR. -

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives t’s funny how music can define an entire come one of Miller’s biggest hits, “Chattanooga We also get some wonderful Harry Warren and era, and Glenn Miller’s unique sound did Choo Choo,” which, in the film, is a spectacu- Mack Gordon songs, including “At Last” (the Ijust that. It is not possible to think of World lar production number with Dandridge and The castoff from Sun Valley Serenade), “Serenade War II without thinking of the Miller sound. It Nicholas Brothers. Another great new song, “At in Blue,” “People Like You and Me,” and the was everywhere – pouring out of jukeboxes, Last,” was also recorded for the film, but wasn’t instant classic, “I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo.” radios, record players. Miller had been strug- used, except as background music for several The latter was, like “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” gling in the mid-1930s and was dejected, but scenes. The song itself would end up in the nominated for an Oscar for Best Song. It knew he had to come up with a unique sound next Miller film. lost to a little Irving Berlin song called “White to separate him from all the others – and, of Christmas.” course, the sound he came up with was spec- “Chattanooga Choo Choo” hit number one on tacular and the people ate it up. His song the Billboard chart in December of 1941 and George Montgomery’s trumpet playing was “Tuxedo Junction” sold 115,000 copies in one stayed there for nine weeks. The song was dubbed by Miller band member, Johnny Best week when it was released. -

Jonathan Friedlander Collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4779r5hf Online items available Finding Aid for the Jonathan Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006 Processed by Lorraine Pratt (2006), Sina Rahmadi (2007), and Audra Eagle (2008) in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Bachli, 2008; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Jonathan 1314 1 Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006 Descriptive Summary Title: Jonathan Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana Date (inclusive): 1875-2006 Collection number: 1314 Creator: Friedlander, Jonathan. Extent: 33 boxes (16.5 linear feet)21 oversize boxes Abstract: The several thousand items contained in the Middle Eastern Americana collection document the substantial and significant presence of the Middle East in the annals of American popular culture. Over the course of more than 150 years and well into the present public interest in the Middle East has engendered a consumer appetite for a material culture that ranges from popular fiction and cinema to tobacco and coffee. In all its parts and subsets this diverse and multifaceted collection is geared for academic research and scholarly exploration of issues related to the representation of the Middle East in various popular culture domains including literature, cinema, music, photography, graphics and visual art, the performing arts, and entertainment. -

Moroccan Titles Thank You for Choosing to Receive Information About New Titles from African Books Collective

moroccaN titles Thank you for choosing to receive information about New Titles from African Books Collective. Included in this special mailer are titles from MoroCCo published by EdITIoNs du sIroCCo and sENso uNICo EdITIoNs. All titles featured here can be ordered worldwIdE at www.africanbookscollective.com. Checkout in North America is through PayPal and outside North America through Google. or you can send your orders to: [email protected]. Featured title Nass el GhiwaNe Omar Sayed with a foreword by Martin scorsese this is the amazing story of the Moroccan musical band Nass el Ghiwane is related for the first time. omar sayed’s story is backed by accounts and articles by well-known figures highlighting the major aspects of Nass El Ghiwane’s border-crossing legend. set up at the beginning of the seventies at Hay Mohammadi, one of Casablanca most deprived areas, the band aroused enthusiasm and quickly became the “spokesman of the voiceless”. read more editioNs du sirocco coNtes aNd leGeNdes populaires du maroc Doctoresse Legey “I collected all these tales in Marrakesh. More fortunate than many folklorists who had to ask intermediaries, I collected them directly in the main harems of Marrakesh, on Jâma ‘el- Fna square, with public storytellers or at my surgery, where si El Hasan or lalla ‘Abbouch came to sit and talk. I transcribed these tales in French, as soon as they were told to me and then, to be absolutely sure not to have misinterpreted, nor forgotten any particular expression, I would tell them myself in Arabic to my storytellers. so I can assert that the version I give is as closely related as possible to the tale I heard.” - d. -

Alien Species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010

Mediterranean Marine Science Review Article Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net Alien species in the Mediterranean Sea by 2010. A contribution to the application of European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). Part I. Spatial distribution A. ZENETOS 1, S. GOFAS 2, M. VERLAQUE 3, M.E. INAR 4, J.E. GARCI’A RASO 5, C.N. BIANCHI 6, C. MORRI 6, E. AZZURRO 7, M. BILECENOGLU 8, C. FROGLIA 9, I. SIOKOU 10 , D. VIOLANTI 11 , A. SFRISO 12 , G. SAN MART N 13 , A. GIANGRANDE 14 , T. KATA AN 4, E. BALLESTEROS 15 , A. RAMOS-ESPLA ’16 , F. MASTROTOTARO 17 , O. OCA A 18 , A. ZINGONE 19 , M.C. GAMBI 19 and N. STREFTARIS 10 1 Institute of Marine Biological Resources, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, P.O. Box 712, 19013 Anavissos, Hellas 2 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Ma ’laga, E-29071 Ma ’laga, Spain 3 UMR 6540, DIMAR, COM, CNRS, Université de la Méditerranée, France 4 Ege University, Faculty of Fisheries, Department of Hydrobiology, 35100 Bornova, Izmir, Turkey 5 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Ma ’laga, E-29071 Ma ’laga, Spain 6 DipTeRis (Dipartimento per lo studio del Territorio e della sue Risorse), University of Genoa, Corso Europa 26, 16132 Genova, Italy 7 Institut de Ciències del Mar (CSIC) Passeig Mar tim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, E-08003 Barcelona, Spain 8 Adnan Menderes University, Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Department of Biology, 09010 Aydin, Turkey 9 c\o CNR-ISMAR, Sede Ancona, Largo Fiera della Pesca, 60125 Ancona, Italy 10 Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, P.O. -

Legal Protection for Literary Titles

6 Legal Protection for Literary Titles A Marxist Case Study Terence P. Ross 946 was a great year for the motion Our Lives – are on the American Film In- picture industry in the United States and stitute’s list of the 100 Greatest Movies. But for movie goers. With the repeal of the at least ten more films from 1946 would be wartime excess profits tax, total net industry recognized by critics and film-goers of today 1profits after taxes soared from $89 million in as classics, still well worth viewing.2 These 1945 to $190 million in 1946. Equally impres- include: sive, 4.7 billion movie tickets were sold in the Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, starring United States, making 1946 Hollywood’s all- Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman; time peak attendance year.1 And, although John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, some might be tempted to attribute these starring Henry Fonda; increases to the expansion of the movie- Charles Vidor’s Gilda, starring Rita going public with the return of soldiers, sail- Hayworth and Glenn Ford; ors and marines from overseas, the more Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always likely reason is simply the phenomenal qual- Rings Twice, starring Lana Turner and ity of movie offerings in 1946. John Garfield; Two films released in 1946 – Frank Cap- Clarence Brown’s The Yearling, starring Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman; ra’s Christmas classic, It’s A Wonderful Life, and William Wyler’s drama of war veterans King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun, starring Joseph Cotton, Gregory Peck and Lio- adjusting to civilian life, The Best Years Of nel Barrymore; Terence Ross is a partner in the Washington, DC, office of Gibson, Dunn s Crutcher LLP engaged in the practice of intellectual property law.