Kim Jong Il Biography 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 42/Friday, March 2, 2018/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 42 / Friday, March 2, 2018 / Notices 9085 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: meeting. Members of the public may applicable legal criteria were satisfied. Michael R. Brickman, Deputy contact the OCC via email at MSAAC@ All property and interests in property Comptroller for Thrift Supervision, OCC.treas.gov or by telephone at (202) subject to U.S. jurisdiction of these (202) 649–5420, Office of the 649–5420. Members of the public who persons, and these vessels, are blocked, Comptroller of the Currency, are deaf or hearing impaired should call and U.S. persons are generally Washington, DC 20219. (202) 649–5597 (TTY) by 5:00 p.m. EDT prohibited from engaging in transactions SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: By this on Wednesday, March 14, 2018, to with them. notice, the OCC is announcing that the arrange auxiliary aids such as sign DATES: See SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION MSAAC will convene a meeting on language interpretation for this meeting. section. Attendees should provide their full Wednesday, March 21, 2018, at the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: OCC’s offices at 400 7th Street SW, name, email address, and organization, if any. For security reasons, attendees OFAC: Associate Director for Global Washington, DC 20219. The meeting is Targeting, tel.: 202–622–2420; Assistant open to the public and will begin at 8:30 will be subject to security screening procedures and must present a valid Director for Sanctions Compliance & a.m. EDT. The purpose of the meeting Evaluation, tel.: 202–622–2490; is for the MSAAC to advise the OCC on government-issued identification to enter the building. -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

Osu!Monthly #3 February 2018 Art: Leisss

osu!monthly #3 February 2018 Art: Leisss News Highlights Keep up to date with Check out the most the latest circle clicking exciting highlights of action! the month! Interview & More! An interview with Toy CNY celebrations, Anti- on Project Loved! Meta, and Puzzles! CONTENTS OSU!MONTHLY NEWS: JAN 2018 Pages 4 & 5 EDITORS LETTER Catch up on the latest events in the osu! community for the month of Welcome back to another edition of the osu!monthly! It’s been a while January! since we’ve published one of these - regrettably we found ourselves skipping an issue, but we’re happy to be back! THE INSIDE CIRCLE #5: PROJECT LOVED Pages 6 & 7 We have a couple changes in mind for 2018. For one, we aim to provide We interview Toy, tournament player extraordinaire and leader of the more interactive content - expect to see more puzzles and polls in Loved Captain’s Pick community project. This is our chance to find out a bit the near future! We have also fixed our dating system to accurately more about Project Loved! reflect the magazine’s pull date - hopefully this has alleviated some confusion as to the magazine’s relevance, and will make planning and THE INSIDE CIRCLE #6: ANTI-META IN OSU!MANIA designing for themed content much easier. Thus, do not be alarmed Pages 8 - 11 that this release is dated for February 2018, instead of January 2018. We interview Kamikaze, an osu!mania BN who is certainly no stranger to anti-meta keymodes. Hopefully he can help shed some light on this As always, feedback and suggestions would be very much appreciated. -

Anecdotes of Kim Jong Il's Life 2

ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 ANECDOTES OF KIM JONG IL’S LIFE 2 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA JUCHE 104 (2015) At the construction site of the Samsu Power Station (March 3, 2006) At the Migok Cooperative Farm in Sariwon (December 3, 2006) At the Ryongsong Machine Complex (November 12, 2006) In a fish farm at Lake Jangyon (February 6, 2007) At the Kosan Fruit Farm (May 4, 2008) At the goat farm on the Phyongphung Tableland in Hamju County (August 7, 2008) With a newly-wed couple of discharged soldiers at the Wonsan Youth Power Station (January 5, 2009) At the Pobun Hermitage in Mt. Ryongak (January 17, 2009) At the Kumjingang Kuchang Youth Power Station (November 6, 2009) CONTENTS 1. AFFECTION AND TRUST .......................................................1 “Crying Faces Are Not Photogenic”........................................1 Laughter in an Amusement Park..............................................2 Choe Hyon’s Pistol ..................................................................3 Before Working Out the Budget ..............................................5 Turning “100m Beauty” into “Real Beauty”............................6 The Root Never to Be Forgotten..............................................7 Price of Honey .........................................................................9 Concrete Stanchions Removed .............................................. 10 -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE North Korean Literature: Margins of Writing Memory, Gender, and Sexuality A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Immanuel J Kim June 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Kelly Jeong, Chairperson Professor Annmaria Shimabuku Professor Perry Link Copyright by Immanuel J Kim 2012 The Dissertation of Immanuel J Kim is approved: _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the Korea Foundation for funding my field research to Korea from March 2010 to December 2010, and then granting me the Graduate Studies Fellowship for the academic year of 2011-2012. It would not be an overstatement for me to say that Korea Foundation has enabled me to begin and complete my dissertation. I would also like to thank Academy of Korean Studies for providing the funds to extend my stay in Korea. I am grateful for my advisors Professors Kelly Jeong, Henk Maier, and Annmaria Shimabuku, who have provided their invaluable comments and criticisms to improve and reshape my attitude and understanding of North Korean literature. I am indebted to Prof. Perry Link for encouraging me and helping me understand the similarities and differences found in the PRC and the DPRK. Prof. Kim Chae-yong has been my mentor in reading North Korean literature, opening up opportunities for me to conduct research in Korea and guiding me through each of the readings. Without him, my research could not have gotten to where it is today. Ch’oe Chin-i and the Imjingang Team have become an invaluable resource to my research of writers in the Writer’s Union and the dynamic changes occurring in North Korea today. -

Understanding Korea 8 Tourism & Investment

UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT PYONGYANG, KOREA Juche 106 (2017) UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT Foreign Languages Publishing House Pyongyang, Korea Juche 106 (2017) CONTENTS 1. Tourism Resources.................................................1 2. Major Tourist Attractions .......................................1 3. Pyongyang, a Tourist Destination...........................2 4. Monumental Structures in Pyongyang....................2 5. Grand Monument on Mansu Hill............................2 6. Tower of the Juche Idea..........................................3 7. Monument to Party Founding .................................4 8. Chollima Statue.......................................................5 9. Arch of Triumph .....................................................6 10. Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum and Monument to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War ....................7 11. Monument to the Three Charters for National Reunification......................................8 12. Parks and Pleasure Grounds in Pyongyang.............9 13. Moran Hill ............................................................10 14. Kaeson Youth Park ...............................................10 15. Rungna People’s Pleasure Ground........................11 16. Pyongyang, a Time-Honoured City ......................12 17. Royal Tombs in Pyongyang..................................13 18. Mausoleum of King Tangun................................. 13 19. Mausoleum of King Tongmyong.......................... 14 20. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

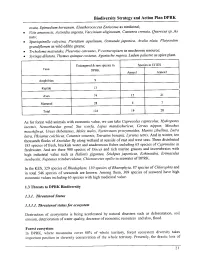

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Korea-Today-2021-0306.Pdf

Monthly Journal (777) C O N T E N T S 2 Second Plenary Meeting of Eighth Central Committee of WPK Held 12 Kim Jong Un Sees Lunar New Year’s Day Performance with Party Central Leadership Body Members 14 Appeal to All Working People Across the Country 15 By Dint of Scientifi c Self-reliance 16 Harnessing of Renewable Energy Propelled 17 Electric Power Management Gets Upgraded 18 By Tapping Local Materials 19 Secret of Increasing Production 20 Ideals for New Victory 21 Guidance for the People’s Well-being Monthly journal Korea Today is available on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 22 Education Highlighted in DPRK 23 Immortal Juche Idea (10) Self-reliance in National Defence 24 Pride of Medical Scientist 24 Authority on Burns Treatment 26 With Sincerity and Devotion 28 True story Front Cover: On March Life and Promise 8 International Women’s Day 30 Vinalon Inventor and His Descendants Photo by courtesy 32 E-commerce Gets Expansive of the KCNA 33 Efforts for Correct and Prompt Weather Forecast 34 How Mun Has Overcome Disability 35 Liquefi ed Rare Earth Draws Attention 36 Small Institute in Woods 37 People Who Strive to Increase Forest Land 38 Songchon County Changes 40 Pacesetter of Costume Culture 41 For Conservation of Water Resources 42 Kimchi, Distinctive Dish of Korea (1) Kimchi and Folklore of Korea 44 Mt Chilbo ( 2 ) Back Cover: Rhododen- 46 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (51) dron blossoms in the snow Ssolmaethagi Photo by Song Tae Hyok 47 Ho Jun and Tonguibogam 48 History Denounces 13502 Edited by An Su Yong Address: Sochon-dong, Sosong District, Pyongyang, DPRK E-mail: fl [email protected] © The Foreign Language Magazines 2021 1 ► amine the plans for this year in detail and fi x and work for implementing the decisions made at the issue them as the decisions of the Party Central Party congress starts and what kind of change is Committee. -

Interaction Member Activity Report North Korea a Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of Interaction Member Agencies in North Korea

InterAction Member Activity Report North Korea A Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of InterAction Member Agencies in North Korea September 2005 Photo by Reuters/Ho Produced by Josh Kearns With the Humanitarian Policy and Practice Unit of 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 701, Washington DC 20036 Phone (202) 667-8227 Fax (202) 667-8236 Website: http://www.interaction.org Table of Contents Map of North Korea 2 Background Summary 3 Report Summary 5 Organizations by Sector Activity 6 Glossary of Acronyms 7 InterAction Member Activity Report Adventist Development and Relief Agency 8 American Friends Service Committee 10 Americares 12 Baptist World Aid 13 Catholic Relief Services 14 Holt International Children’s Services 16 Korean American Sharing Movement 17 Mercy Corps 18 Refugees International 20 US Fund for UNICEF 21 World Vision 24 InterAction Member Activity Report for North Korea 1 September 2005 Map of North Korea Map courtesy of Central Intelligence Agency / World Fact Book InterAction Member Activity Report for North Korea 2 September 2005 Background Summary Since the mid-1990’s, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has experienced a severe food shortfall. Exacerbated by a series of droughts and floods, the DPRK is further plagued by unsafe drinking water supplies, declining public health services, and an energy crisis. Economic mismanagement and a loss of support from North Korea’s traditional communist allies after the end of the Cold War have led to continuing economic decline over the last decade. Food rations under the government’s Public Distribution System (PDS), upon which many North Koreans depend for survival, went into serious decline beginning in 1994. -

1 INFORMAČNÝ LIST PREDMETU Vysoká Škola

INFORMAČNÝ LIST PREDMETU Vysoká škola: Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave Fakulta: Filozofická fakulta Kód predmetu: Názov predmetu: Aktuálne otázky vývoja v Kórei FiF.KVŠ/A- boVS-335/15 Druh, rozsah a metóda vzdelávacích činností: Forma výučby: seminár Odporúčaný rozsah výučby ( v hodinách ): Týždenný: 2 Za obdobie štúdia: 28 Metóda štúdia: prezenčná Počet kreditov: 6 Odporúčaný semester/trimester štúdia: 7. Stupeň štúdia: I. Podmieňujúce predmety: Podmienky na absolvovanie predmetu: aktívna účasť na výučbe, prezentácia, seminárna práca, záverečná písomná skúška (otázky z obsahu kurzu) Výsledky vzdelávania: Nadobudnutie poznatkov o aktuálnom vývoji na Kórejskom polostrove v medzinárodných súvislostiach. Stručná osnova predmetu: - „Beyond 1945“ - historické súvislosti rozdielov medzi severom a juhom Kórejského polostrova - Vývoj záujmov USA, Veľkej Británie a ZSSR o Kóreu počas 2. svetovej vojny - politika a diplomacia Spojencov - mierové konferencie a prijaté dokumenty - vývoj vo Východnej Ázii po roku 1945 - mierová zmluva s Japonskom, vývoj v Číne po r. 1945 - ich vplyv na situáciu na Kórejskom polostrove - Kórea v súvislosti s dekolonializáciou juhovýchodnej Ázie - Dynastia Kimovcov - 7 desaťročí boja o moc - záujmy 4 mocností (USA, Japonska, Ruska a Číny) na Kórejskom polostrove v súčasnosti - Kórejsko-kórejský dialóg: minulosť a perspektívy - Kórejská republika ako súčasť medzinárodného spoločenstva po vstupe do OSN r. 1991 - Vývoj kórejsko-kórejských vzťahov po roku 1990: rola mimovládnych aktérov v dialógu Odporúčaná literatúra: Eckert, Carter J. a kol. Dějiny Koreje. Praha: NLN 2001. Woo, Han-Young. A Review of Korean History, Vol. 3 Modern/Contemporary Era. Paju : Kyongsaewon, 2010. Kang, Man-gil: History of Contemporary Korea. Global Oriental, 2006. Kindermann, Gottfried-Karl: Der Aufstieg Koreas in der Weltpolitik. Von der Landesöffnung bis zur Gegenwart. -

January 1982–May 1983

KIM IL SUNG WORKS WORKING PEOPLE OF THE WHOLE WORLD, UNITE! KIM IL SUNG WORKS 37 January 1982–May 1983 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA 1 9 9 1 CONTENTS NEW YEAR ADDRESS January 1, 1982 ......................................................................................................................1 ON IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF REFRACTORIES Speech at a Consultative Meeting of the Senior Officials of the Administration Council, January 27, 1982................................................................10 ON SOME TASKS FACING THE CHEMICAL INDUSTRY Speech Delivered at a Consultative Meeting of the Senior Officials of the Chemical Industry, February 9, 1982.........................................................20 ON CONDUCTING SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN KEEPING WITH THE SITUATION IN OUR COUNTRY Speech at the Consultative Meeting of Officials in the Field of Science and Technology, February 17, 1982..................................................................30 ON SOME TASKS IN DEVELOPING SEAFOOD PRODUCTION Speech at an Enlarged Meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, February 18, 1982.........................................46 OPEN LETTER TO ALL VOTERS THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY February 19, 1982 ................................................................................................................68 ON THE ADMINISTRATION COUNCIL’S ORIENTATION OF ACTIVITIES Speech at the First Plenary Meeting of the Administration Council of the Democratic