Attorney General Power, Conduct, and Judgment in Relation to the Work of an Independent Counsel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justices' Profiles Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Supreme Court Preview Conferences, Events, and Lectures 1995 Section 1: Justices' Profiles Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "Section 1: Justices' Profiles" (1995). Supreme Court Preview. 35. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview/35 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview WARREN E. BURGER IS DEAD AT 87 Was Chief Justice for 17 Years Copyright 1995 The New York Times Company The New York Times June 26, 1995, Monday Linda Greenhouse Washington, June 25 - Warren E. Burger, who retired to apply like an epithet -- overruled no major in 1986 after 17 years as the 15th Chief Justice of the decisions from the Warren era. United States, died here today at age 87. The cause It was a further incongruity that despite Chief was congestive heart failure, a spokeswoman for the Justice Burger's high visibility and the evident relish Supreme Court said. with which he used his office to expound his views on An energetic court administrator, Chief Justice everything from legal education to prison Burger was in some respects a transitional figure management, scholars and Supreme Court despite his tenure, the longest for a Chief Justice in commentators continued to question the degree to this century. He presided over a Court that, while it which he actually led the institution over which he so grew steadily more conservative with subsequent energetically presided. -

Affordable Care Act As an Unconstitutional Exercise of Con- Gressional Power

PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA ex rel. KENNETH T. CUCCINELLI, II, in his official capacity as Attorney General of Virginia, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. KATHLEEN SEBELIUS, Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, in her official capacity, Defendant-Appellant. AMERICA’S HEALTH INSURANCE No. 11-1057 PLANS; CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Amici Curiae, AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES; THE ARC OF THE UNITED STATES; BREAST CANCER ACTION; FAMILIES USA; FRIENDS OF CANCER RESEARCH; MARCH OF DIMES FOUNDATION; MENTAL HEALTH AMERICA; NATIONAL BREAST CANCER COALITION; NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR RARE DISORDERS; 2 VIRGINIA v. SEBELIUS NATIONAL PARTNERSHIP FOR WOMEN AND FAMILIES; NATIONAL SENIOR CITIZENS LAW CENTER; NATIONAL WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK; THE OVARIAN CANCER NATIONAL ALLIANCE; AMERICAN NURSES ASSOCIATION; AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS, INCORPORATED; AMERICAN MEDICAL STUDENT ASSOCIATION; CENTER FOR AMERICAN PROGRESS, d/b/a Doctors for America; NATIONAL HISPANIC MEDICAL ASSOCIATION; NATIONAL PHYSICIANS ALLIANCE; CONSTITUTIONAL LAW PROFESSORS; YOUNG INVINCIBLES; KEVIN C. WALSH; AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY; AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY CANCER ACTION NETWORK; AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION; AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION; DR. DAVID CUTLER, Deputy, Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics, Harvard University; DR. HENRY AARON, Senior Fellow, Economic Studies, Bruce and Virginia MacLaury Chair, The Brookings Institution; DR. GEORGE AKERLOF, Koshland Professor of Economics, University of California-Berkeley; DR. STUART ALTMAN, Sol C. Chaikin Professor of National Health Policy, Brandeis University; VIRGINIA v. SEBELIUS 3 DR. KENNETH ARROW, Joan Kenney Professor of Economics and Professor of Operations Research, Stanford University; DR. SUSAN ATHEY, Professor of Economics, Harvard University; DR. -

Portico 2006/3

PORTICO 2006/3 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN TAUBMAN COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PLANNING Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Dean .......................................................................................1 Letters .....................................................................................................3 College Update Global Place: practice, politics, and the polis TCAUP Centennial Conference #2 .....................................................4 <<PAUSE>> TCAUP@100 .....................................................................6 Centennial Conference #1 ................................................................7 Student Blowout ................................................................................8 Centennial Gala Dinner ....................................................................9 Faculty Update.....................................................................................10 Honor Roll of Donors ..........................................................................16 Alumni Giving by Class Year ..............................................................22 GOLD Gifts (Grads of the Last Decade) ...........................................26 Monteith Society, Gifts in memory of, Gifts in honor of ................27 Campaign Update................................................................................27 Honor Roll of Volunteers ....................................................................28 Class Notes ..........................................................................................31 -

2010 PEC 40 Year Anniversary

CONSERVATION THROUGH COOPERATION PCECoSntatffeanndtOs ffices . 2 PEC Board of Directors . 3 Honorary Hon. Edward G. Rendell Anniversary Governor About The Pennsylvania Committee Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Environmental Council . 5 Hon. Mark Schweiker . Former Governor Building on a Proud Past 7 Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Don Welsh – President, Hon. Tom Ridge Pennsylvania Environmental Council Former Governor At Work Across Commonwealth of Pennsylvania the Commonwealth . 9 Hon. Dick Thornburgh Former Governor Tony Bartolomeo – Chairman of the Board, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Environmental Council Hon. John Hanger PEC at 40 . 10 Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection From Humble Beginnings: A look back at the Pennsylvania Hon. Kathleen A. McGinty Environmental Council’s first forty years Former Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection A Commitment to Advocacy . 17 Hon. David E. Hess Former Secretary PEC Leadership Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Through the Years . 18 Hon. James M. Seif Former Secretary 40 Under 40 . 20 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection The Green Generation Has Come of Age! Hon. Arthur A. Davis . Former Secretary 40 Below! 36 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources Meet PEC’s Own Version of the “Under 40” Crowd Hon. Nicholas DeBenedictis Shutterbugs . 49 Former Secretary Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources PEC’s Photo Contest Showcases Amateur Hon. Peter S. Duncan Talent…and Spectacular Results! Former Secretary At Dominion, our dedication to a healthy clean up streams and parks, and assist Beyond 40 . 76 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources ecosystem goes well beyond our financial established conservation groups. Environmental investment in science and technology. It also stewardship is something that runs throughout Looking Forward Hon. -

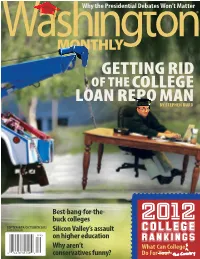

Getting Rid of Thecollege Loan Repo Man by STEPHEN Burd

Why the Presidential Debates Won’t Matter GETTING RID OF THECOLLEGE LOAN REPO MAN BY STEPHEN BURd Best-bang-for-the- buck colleges 2012 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 $5.95 U.S./$6.95 CAN Silicon Valley’s assault COLLEGE on higher education RANKINGS Why aren’t What Can College conservatives funny? Do For You? HBCUsHow do tend UNCF-member to outperform HBCUsexpectations stack in up successfully against other graduating students from disadvantaged backgrounds. higher education institutions in this ranking system? They do very well. In fact, some lead the pack. Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington Monthly’s College Rankings UNCF “Historically black and single-gender colleges continue to rank Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute Institute for Capacity Building well by our measures, as they have in years past.” —Washington Monthly Serving Students and the Public Good: HBCUs and the Washington “When it comes to moving low-income, first-generation, minority Monthly’s College Rankings students to and through college, HBCUs excel.” • An analysis of HBCU performance —UNCF, Serving Students and the Public Good based on the College Rankings of Washington Monthly • A publication of the UNCF Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute To receive a free copy, e-mail UNCF-WashingtonMonthlyReport@ UNCF.org. MH WashMonthly Ad 8/3/11 4:38 AM Page 1 Define YOURSELF. MOREHOUSE COLLEGE • Named the No. 1 liberal arts college in the nation by Washington Monthly’s 2010 College Guide OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS • Named one of 45 Best Buy Schools for 2011 by 830 WESTVIEW DRIVE, S.W. The Fiske Guide to Colleges ATLANTA, GA 30314 • Named one of the nation’s most grueling colleges in 2010 (404) 681-2800 by The Huffington Post www.morehouse.edu • Named the No. -

DEPARTMENT of JUSTICE AUTHORIZATION for APPROPRIATIONS, Nscal YEAR 1992 (Part 2—Appendix)

^.'^^ \Ki DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS, nSCAL YEAR 1992 (Part 2—Appendix) ( '^^R 26 1992 HEARINGS BETORE TMS;„^^^^ :i) H^^lSjl^' COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 11 AND 18, 1991 Serial No. 12 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary U.S. GOVERNMENT PaiNTING OFFICE S2-«70 o WASHINGTON : 199S For sale by the U.S. GovemmenI Priming Office Superinlendem of Documents. Congres!>MMial Sales OfTice, Washington. DC 20402 ISBN 0-16-037645-9 CX)MMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JACK BROOKS, Texas, Chairman DON EDWARDS, California HAMILTON FISH, JR., New York JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California ROMANO L. MAZZOLI, Kentucky HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois WILLIAM J. HUGHES, New Jersey F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., MIKE SYNAR, Oklahoma Wisconsin PATRiaA SCHROEDER, Colorado BILL McCOLLUM. Florida DAN GLICKMAN, Kansas GEORGE W GEKAS, Pennsylvania BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York D. FRENCH SLAUGHTER, JR., VirginU EDWARD F. FEIGHAN, Ohio LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas HOWARD L. HERMAN, California CRAIG T. JAMES, Florida RICK BOUCHER, Virginia TOM CAMPBELL, California BARLEY O. STAGGERS, JR., West Virginia STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JOHN BRYANT, Texas JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota MEL LEVINE, California GEORGE E. SANGMEISTER, lUinois CRAIG A. WASHINGTON, Texas PETER HOAGLAND, Nebraska MICHAEL J. KOPETSKl, Oregon JOHN F. REED, Rhode Island JONATHAN R YAROWSKY, General Counael ROBERT H. BRINK, Deputy General Counsel JAMES E. LKWIN, Chief Investigator ALAN F. COFTKY, JR., Minority Chief Counsel (II) Cm 3^-*3e%L/ HZ-'^lG^^ A I ^^\..^ CONTENTS X f + APPENDIX Pagp Hon. -

Download Legal Document

Appeal: 11-6480 Document: 73-1 Date Filed: 07/18/2011 Page: 1 of 37 No. 11-6480 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT ESTELA LEBRON, et al. Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. DONALD RUMSFELD, et al. Defendants-Appellees. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA BRIEF OF FORMER ATTORNEYS GENERAL WILLIAM P. BARR, EDWIN MEESE III, MICHAEL B. MUKASEY, AND DICK THORNBURGH AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF AFFIRMANCE Andrew G. McBride* William S. Consovoy Claire J. Evans WILEY REIN LLP 1776 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 TEL: (202) 719-7000 FAX: (202) 719-7049 EMAIL: [email protected] Dated: July 18, 2011 Counsel for Amici Curiae * Counsel of Record Appeal: 11-6480 Document: 73-1 Date Filed: 07/18/2011 Page: 2 of 37 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................... ii STATEMENT OF IDENTITY, INTEREST IN CASE, AND SOURCE OF AUTHORITY TO FILE .....................................................................1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................................................................3 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................7 I. THESE FORMER DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE OFFICIALS DID NOT VIOLATE PADILLA’S “CLEARLY ESTABLISHED” RIGHTS BY DETAINING HIM AS AN ENEMY COMBATANT ......................................................................7 II. QUALIFIED IMMUNITY IS ESPECIALLY APPROPRIATE GIVEN THAT THIS BIVENS -

Communications Between OLC And

CHARLES E. SCHUMER DEMOCRATIC LEADER NEW YORK mnitcd ~tatcs ~cnotc WASHINGTON, DC 20510 May 2, 2019 The Honorable William P. Barr Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Attorney General Barr: Your testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee yesterday raised a number of very serious concerns about your understanding of your role in our government, your commitment to the rule of law and your fitness to continue leading the Department of Justice. Among the many disturbing things you said, I was particularly troubled by your statement that if the president feels an investigation "is based on false allegations, the president does not have to sit there constitutionally and allow it to run its course. The president could terminate that proceeding and not have it be corrupt intent because he was being falsely accused." If this idea is how our nation is governed, we will no longer be the democracy Americans think we are. I understood from the memorandum you sent to Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein in June of 2018 that you subscribe to a philosophy in which the executive is exalted above the other co equal branches of government. But this was the first time I had heard you articulate, as Attorney General, this starkly extremist view. Such a statement, in my view - and I believe most Americans would agree - shows complete disregard for the carefully-designed system of checks and balances the Framers enshrined in our Constitution. If these views are truly your views, you do not deserve to be Attorney General. -

1981 NGA Annual Meeting

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1981 SEVENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING Atlantic City, New Jersey August 9-11, 1981 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington, D.C. 20001 These proceedings were recorded by Mastroianni and Formaroli, Inc. Price: $8.50 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 © 1982 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United States of America ii CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vi Attendance x Guest Speaker xi Program xii PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks Presentation of NGA Awards for Distinguished Service to State Government 1 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy 5 Positions Criminal Justice and Public Protection 5 Human Resources 6 Energy and Environment 15 Community and Economic Development 17 Restoring Balance to the Federal System: Next Stepon the Governors' Agenda 19 Remarks of Vice President George Bush 24 Report of the Executive Committee and Voting on Proposed Policy Position 30 Salute to Governors Completing Their Terms of Office 34 Report of the Nominating Committee 36 Remarks of the New Chairman 36 Adjournment 39 iii APPENDIXES I. Roster of Governors 42 II. Articles of Organization 44 ill. Rules of Procedure 51 IV. Financial Report 55 V. Annual Meetings of the National Governors' Association 58 VI. Chairmen of the National Governors' Association, 1908-1980 60 iv EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, 1981* George Busbee, Governor of Georgia, Chairman Richard D. Lamm, Governor of Colorado John V. -

General Information About Shippensburg University

Red Raider Basketball 2008-2009 Derrick Graff Brian Oleksiak WWW.SHIPRAIDERS.COM 2008-09 Men’s Basketball Exhibitions in Canada Red Raider Basketball 3 General Information Shippensburg Quick Facts Official Name of University: Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania Table of Contents Member: The Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education Location and Zip Code: Shippensburg, Pa. 17257 General Information President: Dr. William N. Ruud About Shippensburg University .................................... 4 Undergraduate Enrollment: 6,600 Academic Programs....................................................... 5 Overall Enrollment: 7,600 Founded: 1871 Academics and Athletics ............................................... 6 Colors: Red and Blue Academic Support Services for Student Athletes .......... 6 Nickname: Red Raiders Athletic Administration ................................................ 7 Conference: Pennsylvania State Athletic Heiges Field House ....................................................... 8 Other Affiliations: NCAA Division II The Coaches Director of Athletics: Dr. Roberta Page Athletics Office: (717) 477-1541 Head Coach ...........................................................10-11 Head Coach: Dave Springer (Ohio University ‘84) Coaching Staff ............................................................ 12 Assistant Coaches: Mike Nestor (Shippensburg ‘00/’04M) Season Outlook Todd Johnson (Shippensburg ‘07) Rosters ......................................................................... 14 Herb Bowers (Shippensburg -

Brief Amici Curiae of Former U.S. Attorneys General William P. Barr, Et Al. Filed. VIDED

Nos. 15-1359, 15-1358, 15-1363 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JOHN D. ASHCROFT, former U.S. Attorney General, and ROBERT MUELLER, former Director of the FBI, Petitioners, v. IBRAHIM TURKMEN, et al., Respondents. (Caption continued on inside cover) On Petitions for Writs of Certiorari to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit BRIEF OF FORMER U.S. ATTORNEYS GENERAL WILLIAM P. BARR, ALBERTO R. GONZALES, EDWIN MEESE III, MICHAEL B. MUKASEY, AND DICK THORNBURGH; FORMER FBI DIRECTORS WILLIAM S. SESSIONS AND WILLIAM H. WEBSTER; AND WASHINGTON LEGAL FOUNDATION AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS Richard A. Samp (Counsel of Record) Mark S. Chenoweth Washington Legal Foundation 2009 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, DC 20036 202-588-0302 [email protected] Date: June 8, 2016 No. 15-1358 JAMES W. ZIGLAR, Petitioner, v. IBRAHIM TURKMEN, et al., Respondents. No. 15-1363 DENNIS HASTY and JAMES SHERMAN, Petitioners, v. IBRAHIM TURKMEN, et al., Respondents. QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the judicially inferred damages remedy under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971), should be extended to the novel context of this case, which seeks to hold the former Attorney General, former Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and other senior federal government officials personally liable for policy decisions made about national security and immigration in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. 2. Whether those senior officials are entitled to qualified immunity for their alleged role in the treatment of Respondents, because it was not clearly established that aliens legitimately arrested during the September 11 investigation could not be held in restrictive conditions until the FBI confirmed that they had no connections with terrorism. -

Download a PDF Version Here

WITHIN REACH 2016 ANNUAL REPORT PUTTING HOPE AND OPPORTUNITY WITHIN REACH Sometimes life’s obstacles seem insurmountable, especially if you are a child or teen from the inner-city where so many live in poverty, have unstable housing, live in food-insecure households and even face violence. For these youth, the things you and I take for granted often seem out of reach—safety, nutritious meals, academic TRUSTEES support, positive role models, a pathway to college and a career. With help from our caring donors and partners, Boys & Girls Clubs is able to put these resources within Christopher S. Abele* Richard R. Pieper, Sr. Barry Allen James R. Popp* the reach of kids who need them. In fact, your support enabled us to serve nearly Bevan K. Baker Robert B. Pyles 42,000 youth in 2016. James T. Barry III David F. Radtke* David A. Baumgarten Kristine A. Rappé* Linda Benfield Bethany M. Rodenhuis The following pages will introduce you to Ester, Anthony and a family from our Thomas H. Bentley, III Mark Sabljak William R. Bertha Richard C. Schlesinger Carver Club, just a few of the individuals who are thriving thanks to the resources Thomas M. Bolger Allan H. Selig you have made accessible through the Clubs. Their success stories are a reflection Elizabeth Brenner John S. Shiely OFFICERS Brian Cadwallader Thelma A. Sias of the support you have poured into the Clubs. Every donation, volunteer hour and Tonit Calaway Patrick Sinks offer of partnership becomes an opportunity for Boys & Girls Clubs to be a lifeline Tina M. Chang Daniel Sinykin Susan Ela G.