Discovering the Canadian Literary Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall(14 September 1883 – 19 April 1922) Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall (September 14, 1883, Gunnersbury, London, – April 19, 1922, Vancouver), was a Canadian writer who was born in England but lived in Canada from the time she was seven. She was once "thought to be the best Canadian poet of her generation." Marjorie Pickthall was born in 1883 in the west London district of Gunnersbury, to Arthur Christie Pickthall, a surveyor and the son of a Church of England clergyman, and Elizabeth Helen Mary Pickthall (née Mallard), daughter of an officer in the Royal Navy, part Irish and part Huguenot. According to her father, Pickthall had planned her career before she was six; she would be a writer and illustrator of books. Her parents encouraged her artistic talents with lessons in drawing and music; an accomplished violinist, she continued studying violin until she was twenty. By 1890, Pickthall and her family had moved to Toronto, Canada where her father initially worked at the city’s waterworks before becoming an electrical draftsman. Her only brother died in 1894. Marjorie was educated at the Church of England day school on Beverley Street in Toronto, (possibly St. Mildred's College) and from 1899 at the Bishop Strachan School. She developed her skills at composition and made lasting friendships at these schools, despite suffering poor health, suffering from headaches, dental, eye and back problems. -

AAM. Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature, Ddavies

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Davies, D. ORCID: 0000-0002-3584-5789 (2021). Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black. The Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(1), pp. 1-23. doi: 10.1017/pli.2020.23 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26525/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pli.2020.23 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black Abstract (151 words) Through an extended reading of Canadian author Esi Edugyan’s novel, Washington Black (2018), this article aims to revise and reinsert both the practice of close reading and a radically revised humanism back into recent World(-)Literature debates. -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Introduction

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Canada & Beyond 5 (2015): 27 Liminality and (Trans)Nationalism in the Rethinking of African Canadian Subjectivity: Esi Edugy

Liminality and (Trans)Nationalism in the Rethinking of African Canadian Subjectivity: Esi Edugyan’s The Second Life of Samuel Tyne. Vicent Cucarella-Ramon Universitat de València Canada is a location where…blackness is threatened with psychological evisceration (George Elliott Clarke, Odysseys Home) In a Canadian context, writing blackness is a scary scenario: we are an absented presence always under erasure (Rinaldo Walcott , Black Like Who) Who is to say what a Canadian story looks like, where it should be set, who should be telling it?…Indeed, what is a Canadian at all? (Esi Edugyan, Dreaming of Elsewhere) Introduction The publication of Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness in 1993 marked an ontological shift in the recognition of the diversity and conflict in black experiences and their cultural production. There exists an established consensus on the impact and groundbreaking potential of Gilroy’s work as it propounded a global reconfiguration of the notion of a multilayered black self. Gilroy repositioned black consciousness from the margins to the center, engaging a transnational and transcultural debate that contributed to securing black subjectivity as “a central symbol in the psychological, cultural, and political systems of the West as a whole” (Gilroy 158). However, in the late 1990s Gilroy’s theory generated debates over its shortcomings, namely because new readings of The Black Atlantic pointed out that the social realities of Africa, the Caribbean and Canada were absent from its theoretical -

Download The

READING THE FIELD OF CANADIAN POETRY IN THE ERA OF MODERNITY: THE RYERSON POETRY CHAP-BOOK SERIES, 1925-1962 by Gillian Dunks B.A. (With Distinction), Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gillian Dunks, 2013 ii Abstract From 1925 to 1962, the Ryerson Press published 200 short, artisanally printed books of poetry by emerging and established Canadian authors. Series editor Lorne Pierce introduced the series alongside other nationalistic projects in the 1920s in order to foster the development of an avowedly Canadian literature. Pierce initially included established Confederation poets in the series, such as Charles G.D. Roberts, and popular late-romantic poets Marjorie Pickthall and Audrey Alexandra Brown. In response to shifting literary trends in the 1940s, Pierce also included the work of modernists such as Anne Marriott, Louis Dudek, and Al Purdy. Following Pierre Bourdieu, I read the Ryerson series as a sub-field of literary production that encapsulates broader trends in the Canadian literary field in the first half of the twentieth century. The struggle between late-romantic and modernist producers to determine literary legitimacy within the series constitutes the history of the field in this period. Pierce’s decision to orient the series towards modernist innovation during the Second World War was due to late romantics’ loss of their dominant cultural position as a result of shifting literary tastes. Modernist poets gained high cultural capital in both the Ryerson series and the broader field of Canadian literary production because of their appeal to an audience of male academics whose approval ensured their legitimacy. -

Marjorie Pickthall & the Quest for Poetic Identity

DEMETER'S DAUGHTER Marjorie Pickthall & the Quest for Poetic Identity Diana M. A. Relke M.LARJORIE PICKTHALL sold her first manuscript to the Toronto Globe in 1899, when she was 15 years old.* Her career ended abruptly in 1922, when, at the age of 39, she died in Vancouver of complications following surgery. Perhaps no other Canadian poet has enjoyed such enormous fashionable success followed by such total eclipse. Canadian critics of the early twentieth century "seized on her poems and stories as works of distinction,"1 and some even hailed her as a genius and seer. "More than any other poet of this century," wrote E. K. Brown in 1943, "she was the object of a cult. .. Unacademic critics boldly placed her among the few, the immortal names."2 Brown might also have noted that unreserved praise was lavished on Pickthall by scholarly critics as well. She was admired and encouraged by Pelham Edgar who, at the time of her death, wrote: "Her talent was strong and pure and tender, and her feeling for beauty was not more remarkable than her unrivalled gift for expressing it."3 Archibald MacMechan wrote: "Her death means the silencing of the truest, sweetest singing voice ever heard in Canada."4 Within 18 months of her death no less than ten articles — all overloaded with superlatives — were published in journals and magazines such as The Canadian Bookman, Dalhousie Review, and Saturday Night. In his biography, Marjorie Pickthall: A Book of Remembrance, Lome Pierce includes ten tributes paid in verse to the memory of Marjorie Pickthall by companion poets; Pierce himself writes rhapsodically of her "Colour, Cadence, Contour and Craftsmanship."5 Modern literary historians have taken the opposite view. -

The Group of Seven, AJM Smith and FR Scott Alexandra M. Roza

Towards a Modern Canadian Art 1910-1936: The Group of Seven, A.J.M. Smith and F.R. Scott Alexandra M. Roza Department of English McGill University. Montreal August 1997 A Thesis subrnitted to the Facdty of Graduate Studies and Researçh in partial fiilfiliment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. O Alexandra Roza, 1997 National Library BiMiotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtocl Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OttawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distnibuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. iii During the 19 los, there was an increasing concerted effort on the part of Canadian artists to create art and literature which would afhn Canada's sense of nationhood and modernity. Although in agreement that Canada desperately required its own culture, the Canadian artistic community was divided on what Canadian culture ought to be- For the majority of Canadian painters, wrïters, critics and readers, the fbture of the Canadian arts, especially poetry and painting, lay in Canada's past. -

Giving Ideas Voice

directed by Leonard Enns GIVINg iDEas vOicE Saturday November 11, 8pm St. John the Evangelist, Kitchener Sunday November 12, 3pm St. John’s Lutheran, Waterloo 2017/18 Season Program Horizons – Peter van Dijk Psalm 137 – J. Scott Brubacher Colour of Freedom – Iman Habibi with Amir Haghighi, soloist ~ intermission ~ Song of Invocation – Sheldon Rose Candles – Christine Donkin Tal vez tenemos tiempo – Tarik O’Regan To You before the close of day – Jeff Enns This still room – Jonathan Adams We’d love to visit with you after the concert... please join us to chat over some snacks! Notes & Texts (notes written by L. Enns) With this program, the DaCapo Chamber Choir sets out on a three-year series inspired by the global refugee situation. The series is organized around general themes of Displacement (this season), Resettlement (18/19), and Renewal (19/20). Motivating this plan is the conviction that art is necessary and possibly central to the development and maintenance of civil society, and that it can serve as leaven for peace-making. Today’s global political climate makes this an increasing necessity. The 17/18 season explores the theme of Displacement. The first and final concerts are inspired by several root causes of displacement – war and oppression (today: The Colour of Freedom), and climate change and care for resources (April: This Thirsty Land). Standing between these two, the mid- winter concert (March: Reincarnations) touches on reasons for hope, and on the possibility of transformation. The keystone work of today’s concert is Colour of Freedom by Iranian- Canadian composer Iman Habibi, including texts by Tehran Evin prison survivor Marina Nemat, who has said “If you remain silent, you become an accomplice.” Wilfrid Owen, who was killed 99 years ago, as the “Great War” was exhausting itself, wrote “All a poet can do today is warn. -

Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity : a Study of Marjorie

CANADIAN WOMEN POETS AND POETIC IDENTITY: A STUDY OF MARJORIE PICKTHALL, CONSTANCE LINDSAY SKINNER, AND THE EARLY WORK OF DOROTHY LIVESAY Diana M.A. Relke B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1982 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English 0 Diana M.A. Relke 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy, or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name : Diana M.A. Relke Degree : Doctor of Philosophy Title of Dissertation: Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity: A Study of Marjorie Pickthall, Constance Lindsay Skinner, and the Early Work of Dorothy Livesay. Examining Committee: Chairperson: Chinmoy Banerjee Sandra,,Djwa, Professor, Wnior Supervisor -------a-=--=--J-% ------- b -------- Meredith Kimball, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, S.F.U. --------------. ------------ Diana Brydon, ~ssociatklProfessor, University of British Columbia Date Approved : ii Canadian Women Poets and Poetic Identity: A Study of Marjorie Pickthall , Constance Lindsay Skinner, and the Early Work of -_______^_ -- ----.^ . _ -.___ __ Dorothy Livesay. ---- ---..--- .-------- -.---.----- --- ---- Diana M.A. Re1 ke --- -- ---. ----- - ---* - -.A -- Abstract This study is an examination of the evolution of the female tradition during the transitional period from 1910 to 1932 which signalled the beginning of modern Canadian poetry. Selective and analytical rather than comprehensive and descriptive, it focuses on three representative poets of the period and traces the development of the female poetic self-concept as it is manifested in their work. Critical concepts are drawn from several feminist theories of poetic identity which are based on the broad premise that poetic identity is a function of cultural experience in general and literary experience in particular. -

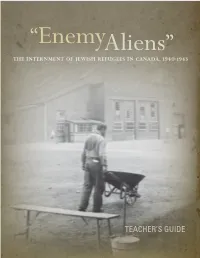

Complete Teachers' Guide to Enemy

“EnemyAliens” The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 TEACHER’S GUIDE “ENEMY ALIENS”: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940-1943 © 2012, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre Lessons: Nina Krieger Text: Paula Draper Research: Katie Powell, Katie Renaud, Laura Mehes Translation: Myriam Fontaine Design: Kazuko Kusumoto Copy Editing: Rome Fox, Anna Migicovsky Cover image: Photograph of an internee in a camp uniform, taken by internee Marcell Seidler, Camp N (Sherbrooke, Quebec), 1940-1942. Seidler secretly documented camp life using a handmade pinhole camera. − Courtesy Eric Koch / Library and Archives Canada / PA-143492 Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre 50 - 950 West 41st Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 2N7 604 264 0499 / [email protected] / www.vhec.org Material may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes provided that the publisher and author are acknowledged. The exhibit Enemy Aliens: The Internment of Jewish Refugees in Canada, 1940 – 1943 was generously funded by the Community Historical Recognition Program of the Department of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Canada. With the generous support of: Oasis Foundation The Ben and Esther Dayson Charitable Foundation The Kahn Family Foundation Isaac and Sophie Waldman Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Foundation Frank Koller The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre gratefully acknowledges the financial investment by the Department of Canadian Heritage in the creation of this online presentation for the Virtual Museum of Canada. Teacher’s Guide made possible through the generous support of the Mordehai and Hana Wosk Family Endowment Fund of the Vancouver Holocaust Centre Society. With special thanks to the former internees and their families, who generously shared their experiences and artefacts in the creation of the exhibit. -

Reading the Field of Canadian Poetry in the Era of Modernity: the Ryerson Poetry Chap-Book Series, 1925-1962

READING THE FIELD OF CANADIAN POETRY IN THE ERA OF MODERNITY: THE RYERSON POETRY CHAP-BOOK SERIES, 1925-1962 by Gillian Dunks B.A. (With Distinction), Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gillian Dunks, 2013 ii Abstract From 1925 to 1962, the Ryerson Press published 200 short, artisanally printed books of poetry by emerging and established Canadian authors. Series editor Lorne Pierce introduced the series alongside other nationalistic projects in the 1920s in order to foster the development of an avowedly Canadian literature. Pierce initially included established Confederation poets in the series, such as Charles G.D. Roberts, and popular late-romantic poets Marjorie Pickthall and Audrey Alexandra Brown. In response to shifting literary trends in the 1940s, Pierce also included the work of modernists such as Anne Marriott, Louis Dudek, and Al Purdy. Following Pierre Bourdieu, I read the Ryerson series as a sub-field of literary production that encapsulates broader trends in the Canadian literary field in the first half of the twentieth century. The struggle between late-romantic and modernist producers to determine literary legitimacy within the series constitutes the history of the field in this period. Pierce’s decision to orient the series towards modernist innovation during the Second World War was due to late romantics’ loss of their dominant cultural position as a result of shifting literary tastes. Modernist poets gained high cultural capital in both the Ryerson series and the broader field of Canadian literary production because of their appeal to an audience of male academics whose approval ensured their legitimacy.