View, Can Really Have Scored out in the Busy World.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health 'Gen Y'

MAGAZINE BestJetEN ROUTE TO that’s withann an E get ready for ‘gen y’ a toast to health maritime VOL.25 | NO.1 | SPRING | 2008 Canada Post Publications Mail Return undeliverable Canadian Agreement No. 40065040 addresses to: Alumni Office Dalhousie University Halifax NS B3H 3J5 If this were a hockey team, they’d all be forwards. Meet the Dalhousie fundraising team. Play makers. Team players. Leaders. An eclectic group of dedicated professionals with one goal – a stronger Dalhousie. If you haven’t met them yet, you will. Relationship building is forefront on their agenda, every day. For more information or to schedule lunch, give them a call at 1.800.565.9969. LEFT TO RIGHT, FRONT ROW: Rhonda Harrington, Director of Advancement, Faculty of Medicine; Ann Vessey, Planned Giving Officer; Suzanne Huett, Director, Advancement Strategy; Linda Crockett, Director, Global Gifts; Dawn Ferris, Administrative Assistant; Sharon Gosse, Administrative Assistant. LEFT TO RIGHT, BACK ROW: Rosemary Bulley, Development Officer, Engineering & Computer Science; Mary Lou Crowley, Development Officer, Health Professions; John MacDonald, Director, External Relations, Faculty of Management; Chris Steeves, Development Officer, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences; Diane Chisholm, Development Officer, Law; Jennifer Laurette, Development Officer, Dentistry. Not Pictured: Wendy McGuinness, Director, Planned Giving; Ron Mitton, Sr. Advisor, Corporations & Foundations; Debbie Bright, Adminstrative Assistant DaMAGAZINE l h o u s i e 22Improving the health of our Maritime community Understanding sleep 18The ‘millennials’ disorders, hearing are coming to an problems and patient office near you safety. Extending the reach of specialists through a The millennial generation bedside robot. Volunteering 10Culture club is beginning to graduate in a developing country with and is heading out into inter-professional health Kidding aside, they’ve got to 14Reading between the labour market in care teams. -

Anne-Girls: Investigating Contemporary Girlhood Through Anne with an E

Title Page ANNE-GIRLS: INVESTIGATING CONTEMPORARY GIRLHOOD THROUGH ANNE WITH AN E by Alison Elizabeth Hnatow Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Alison Elizabeth Hnatow It was defended on November 13, 2020 and Approved by Julie Beaulieu, PhD, Lecturer, DAS, Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies Geoffrey Glover, PhD, Lecturer II, DAS, English Marah Gubar, PhD, Associate Professor, Literature at Massachusetts Institute Technology Committee Chair: Courtney Weikle-Mills, PhD, Associate Professor, DAS, English ii Copyright © Alison Elizabeth Hnatow 2020 iii Anne-Girls: Investigating Contemporary Girlhood Through Anne with an E Alison Elizabeth Hnatow, B.Phil University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Anne of Green Gables is a 1908 coming of age novel by L.M. Montgomery. Adapted into over 40 multimedia projects since its publication, it has a significant historical and cultural presence. This research blends feminist media and literature analysis in an investigation of the representation of girlhood in Anne with an E, the 2017 to 2019 CBC & Netflix television program. This work focuses on Anne with an E, the Kevin Sullivan 1984 film, the 1934 George Nicholls Jr. film, and the original novel based on Anne’s Bildungsroman characteristics. Through the analysis of how Anne and the narrative interact with concepts of gender, race, class, sexuality, and ability status, emerges how the very definition of what it means to be a ‘girl’ and how it has changed. -

Before Green Gables by Budge Wilson Ebook

Before Green Gables by Budge Wilson ebook Ebook Before Green Gables currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Before Green Gables please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 400 pages+++Publisher:::: Berkley; Reprint edition (February 3, 2009)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0425225763+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0425225769+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 1 x 8.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 0425225763 ISBN13 978-0425225 Download here >> Description: This prequel to Anne of Green Gables takes on a rich, real life of its own...I was rapt. (Washington Post)For the millions of readers who devoured the Green Gables series, Before Green Gables is an irresistible treat; the account of how one of literatures most beloved heroines became the girl who captivated the world. As an avid Anne of Green Gables fan, I was desperately wishing for some Anne material that I hadnt read six times already. This was a pretty good attempt on such material. I thought the author really captured Anne well, and thought up some really good back story material. The characters, even the bad ones, werent one-dimensional, so she didnt really make out Anne to be a victim which was so appreciated. However, the stories are very sad for the most part, and of course theyre missing just that spark that only L.M. Montgomery could put into them. Of course, it is fitting because Annes surroundings werent as charming and idyllic as they were in Montgomerys stories, so the book is a good fit into what we know of Annes background. -

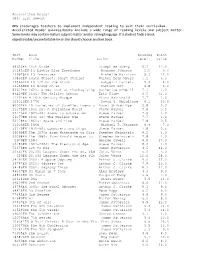

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

2018 Television Report

2018 Television Report PHOTO: HBO / Insecure 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. CREDITS: 12th Floor Contributors: Hollywood, CA 90028 Adrian McDonald Corina Sandru Philip Sokoloski filmla.com Graphic Design: Shane Hirschman @FilmLA FilmLA Photography: Shutterstock FilmLAinc HBO ABC FOX TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 PRODUCTION OF LIVE-ACTION SCRIPTED SERIES 3 THE INFLUENCE OF DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES 4 THE IMPACT OF CORD-CUTTING CONSUMERS 4 THE REALITY OF RISING PRODUCTION COSTS 5 NEW PROJECTS: PILOTS VS. STRAIGHT-TO-SERIES ORDERS 6 REMAKES, REBOOTS, REVIVALS—THE RIP VAN WINKLE EFFECT 8 SERIES PRODUCTION BY LOCATION 10 SERIES PRODUCTION BY EPISODE COUNT 10 FOCUS ON CALIFORNIA 11 NEW PROJECTS BY LOCATION 13 NEW PROJECTS BY DURATION 14 CONCLUSION 14 ABOUT THIS REPORT 15 INTRODUCTION It is rare to find someone who does not claim to have a favorite TV show. Whether one is a devotee of a long-running, time-tested procedural on basic cable, or a binge-watching cord-cutter glued to Hulu© on Sunday afternoons, for many of us, our television viewing habits are a part of who we are. But outside the industry where new television content is conceived and created, it is rare to pause and consider how television series are made, much less where this work is performed, and why, and by whom, and how much money is spent along the way. In this study we explore notable developments impacting the television industry and how those changes affect production levels in California and competing jurisdictions. Some of the trends we consider are: growth in the number of live-action scripted series in production, the influence of digital streaming services on this number, increasing production costs and a turn toward remakes and reboots and away from traditional pilot production. -

Budge Wilson Fonds (MS-2-650)

Dalhousie University Archives Finding Aid - Budge Wilson fonds (MS-2-650) Generated by the Archives Catalogue and Online Collections on April 04, 2019 Dalhousie University Archives 6225 University Avenue, 5th Floor, Killam Memorial Library Halifax Nova Scotia Canada B3H 4R2 Telephone: 902-494-3615 Email: [email protected] http://dal.ca/archives https://findingaids.library.dal.ca/budge-wilson-fonds Budge Wilson fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 4 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Adaptation -

Discourse Analysis of Lucy Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Humanities Soc Sci ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) | ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://scholarsmepub.com/sjhss/ Original Research Article Discourse Analysis of Lucy Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables: An Application of Grice’s Theory Dr. Ibtesam AbdulAziz Bajri1*, Bashaier Al-Amshani2 1Associate Professor, Department of the English Language, College of Languages and Translation, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2 MA student in the Department of the English language, College of Languages and Translation, University of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia DOI:10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.7.3 | Received: 28.06.2019 | Accepted: 10.07.2019 | Published: 23.07.2019 *Corresponding author: Dr. Ibtesam AbdulAziz Bajri Abstract Discourse analysis is an important approach in interpreting denotations beyond the surface meaning of a sentence. Two methods are embodied in this research to examine the underlying meaning of certain literary texts. Since the novel Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Montgomery still poorly explored, this paper investigates the language of selected contexts of the novel according to the theories of cooperative principle and conversational implicature. To clarify, the research sheds light on the nature of discourse in the novel using Grice's four conversational maxims. The violation of maxims can be explained with regard to the theory of conversational implicature. The findings of this paper demonstrate the efficiency of the applied theories. The results signify that all the maxims have been flouted among the selected parts of the novel. The overall assumption of maxims flouting in this novel is due to the protagonist‟s constant detachment of her real world. -

Official Program Official Progr

Friday, July 3rd, 2020 Post Time 6:00pm | Event #5 OFFICIOFFICIAALL PROGR PROGRAAMM WELCOME BACK RACE FANS! • Takeout available at the canteen window located on side of granstand • Reminder to practice social distancing while on grounds www.TruroRaceway.ca @TruroRaceway $2.50 On Track | $2.75 Off Track Photo Credit: Kyle Burton TRURO RACEWAY OFFICAL REGULATIONS AND INFORMATION GENERAL PROGRAM All pari-mutuel pools are calculated and distributed in accordance with the Regulations and Directives as issued by the Canadian Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food (the Regulations), under the approval and supervision of the Canadian Supervision of pari-mutuel betting and drug Pari-Mutuel Agency. All tickets should be held until the race is declared official and prices are posted. Notice boards are control surveillance programs are provided by located in the grandstand. The approximate odds represent only the probable payout price of the win pool at the time they the Federal Minister of Agriculture. All pools are posted & have no bearing on the payout price of any other pool. are calculated and distributed according to ENTRIES AND MUTUEL FIELDS the Regulations set out by the Canadian Pari- “Entry” means two or more horses in the same race which, for the purpose of pari-mutuel betting, are coupled or considered Mutuel Agency. Toll free 1-800-268-8835 as the same betting interest. The most common reason for coupling of horses in Entry is the fact that they are owned by the same person. “Mutual Field” means two or more horses in the same race which, for the purpose of pari-mutuel betting, are coupled because the number of horses in the race exceeds the number which can be handled separately by the pari-mutuel RACING OFFICIALS system. -

Books to Film

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn Drive James Sallis The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson The Woman in Black by Susan Hill The Maze Runner by James Dashner Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden The Hunt for Red October by Tom Moneyball by Michael Lewis Clancy The Godfather by Mario Puzo Books Still Alice by Lisa Genova Carrie by Stephen King The Wolf of Wall Street by Jordan to Belfort Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter by Seth Grahame-Smith Film Pitch Perfect by Mickey Rapkin A Series of Unfortunate Events by These titles and authors Mean Girls based on Queen Bees & Lemony Snicket are available at the Wannabes by Rosalind Wiseman Shaler North Hills Orange Is the New Black based on the Library. All titles are To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper memoir Orange Is the New Black: My Lee Year in a Women's Prison by Piper shelved under the Kerman. author’s last name. P.S. I Love You by Cecelia Ahern Can’t find it? If it’s Brokeback Mountain by Annie Prouix Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen checked out we can Jack Reacher based on the series by request it for you! The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Lee Child Fitzgerald Check for these titles on The Fault in Our Stars by John Green. our Overdrive / Libby Battle Royale by Koushun Takami. and Hoopla apps for an Drive James Sallis ebook, eaudiobook or movie. The Woman in Black by Susan Hill Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood Call the Midwife by Jennifer Worth Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy House of Cards by Michael Dobbs White Queen by Phillipa Gregory Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Ca- pote Mindhunter inspired by Mindhunter: Midnight, Texas by Charlaine Harris Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Gossip Girl by Cecily Von Ziegesar Unit by John E. -

STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Sustainability of a TV Series

Television Coverage Review STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Sustainability of a TV Series A rich ‘World’ Engaging, multi-dimensional characters Compelling themes we want to see explored STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Theme Theme is the expression of the unending, universal struggles of man. STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Themes as ‘Fuel’ Strong themes are the FUEL for great television, because they provide a view into these never-ending struggles we all face. STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS World of Opposites Themes are often expressed as pairs of opposites. Because Life can ONLY be experienced through opposites. Male/female, life/death, good/evil, hot/cold, love/hate, hope/fear, greed/generosity, etc., etc… STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Themes of 3 LBS. What themes drove the action in this series? What ‘universal’ struggle lay beneath its appeal? STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Themes of 3 LBS. Science vs. Mystery The known vs. the unknown, i.e., are we just ‘wires in a box’? Or are we more? The question each case will address. Control vs. Freedom The question all of Hanson’s relationships will address. Logic vs. Instinct Reality vs. Perception STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Themes of ‘Book of Daniel’ What themes drove the action in this series? What ‘universal’ struggle lay beneath its appeal? STORY ANALYSIS - UCLA EXTENSION - RIC GIBBS Themes of ‘Book of Daniel’ Authenticity vs. Social Duty Daniel’s job = Social Duty a minister IS a pillar of the community; moral example; the maintenance of social / spiritual propriety. Daniel’s family life = Authenticity criminal daughter, gay son, alcoholic wife, Vicodin addiction, etc. -

Before Green Gables, Book Excerpt

Before Green Gables Book Excerpt Budge Wilson Chapter 20: Katie Maurice One day, about a month after Eliza's wedding day, and about three weeks after Anne had screamed out her grief in the woods, Anne was putting some dishes away in the old glassed in bookcase that had once belonged to her own family. It was kept in a corner of the house that received very little light. When Anne closed the door, after depositing the dishes, she saw her own reflection in the glass door. She stared and stared at it. In the dimness of the reflection, her freckles had disappeared and her hair looked almost brown. For a moment or two, she thought it was another person. Even after she realized that this was not the case, she clung to the idea. "A friend! A friend!" she kept muttering under her breath. The house was unusually quiet. All four babies and Mrs. Thomas were asleep. Mr. Thomas (who had not had a drink for many weeks) was at work. During this period, Anne was starting to get used to Eliza's absence, although still deeply sad about it. And she rather liked the new baby. He didn't cry as much as the other ones did, and he was much less beautiful than all the bigger Thomas children. In fact, he was quite odd-looking, with an oversized nose and a slight cast in one eye. He wasn't exactly cross-eyed, but he wasn't as oppressively handsome as the older little boys. Anne had always regarded herself as an unattractive-looking person.