Do the Expressive Arts Therapies Aid in Identity Formation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

¿Fiera Salvaje O Flan De Coco? — Un Estudio Sobre La Construcción Metafórica De Género En Letras De Reguetón Común Y Feminista

Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Johanna Hagner (2019) Master’s Thesis, 15 credits Master of Arts in Language and Linguistics ¿Fiera salvaje o flan de coco? — un estudio sobre la construcción metafórica de género en letras de reguetón común y feminista A Wild Beast or a Sweet Dessert? — a study on metaphorical construction of gender in mainstream and feminist reggaeton lyrics Supervisor: Carlos Henderson Examinator: Jordan Zlatev Resumen La presente investigación examina el papel de la metáfora dentro de la construcción de femineidad, masculinidad y sexualidad en las letras del género musical reguetón. Basándose en un corpus representativo del contenido lírico de, por una parte, el reguetón común y, por otra parte, la corriente de reguetón feminista, el estudio toma una perspectiva interdisciplinaria combinando la lingüística cognitiva, el Análisis Crítico del Discurso y la perspectiva de género en su análisis. La tesis arguye que las metáforas animales y las metáforas gastronómicas desempeñan un papel significativo en la transmisión de ideas de género en las letras investigadas. Se sostiene que en el reguetón común, estas metáforas tienden a tener un enfoque en la mujer y en el aspecto físico y seductivo de la femineidad. El reguetón feminista, por su parte, se caracteriza por más variedad en sus conceptualizaciones. En este grupo de material, la interacción seductiva también juega un rol importante; no obstante, el autorretrato femenino y la resistencia a las normas heterosexuales y patriarcales llevan un enfoque mayor. Asimismo, se destaca que en la construcción metafórica del amor homosexual entre mujeres, el reguetón feminista tiende a tener más similitudes con la conceptualización del reguetón común. -

Culturally Me from Margate MS Puerto Rico.Pdf

Culturally Me Culturally MeBy Liana Hill By Liana Hill The language we speak is Spanish. Spanish is derived from a dialect of spoken Latin and was brought to the Iberian Peninsula. Some of the most commonly eaten food in Puerto Rico is Tostones, Mofongo, Alcapurrias, Arroz Con Gandules, Pasteles. Holidays we celebrate are Good Friday April 10, Birthday of José de Diego April 20, Memorial Day May 25, Independence Day July 4, Birthday of Don Luis Muñoz Rivera July 20, Labor Day Sep 7, Day of the Races Oct 12, Veterans Day Nov 11. Some traditions that are celebrated in Puerto Rico are Three Kings Day, Octavitas, Nochebuena, and Parrandas. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-NC The major type of music coming out of Puerto Rico is salsa, the rhythm of the islands. Puerto Rican mainstream acceptance of reggaeton has grown and the genre has become part of popular culture, including a 2006 Pepsi commercial with Daddy Yankee and PepsiCo's choice of Ivy Queen as musical spokesperson for Mountain Dew. Some famous People are Luis Fonsi, Ozuna, Daddy Yankee, Bad Bunny Roberto Clemente, Don Omar, and Luis Guzman Famous Artists • Puerto Rican artists who are represented include José Campeche (1751- 1809) and Francisco Oller (1833-1917). In addition to such European masters as Rubens, van Dyck, and Murillo, the museum features works by Latin American artist, including some by the Mexican Diego Rivera. This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA Guayaberas. The guayabera is the most distinctive and well-known garment from Puerto Rico. -

On the Charts

ON THE CHARTS The chart recaps in this Latin music spe- Ht T,a,ti n un s T(» Latin cial are year -to -date starting with the Dec. 3, 2005, issue, the beginning of the chart Pos. TITLE -Artist Imprint/Label year, through the April 1, 2006, issue. 1 ROMPE Daddy Yankee Pos. DISTRIBUTOR (Na Charted Titles) Recaps for Top Latin Albums are based 2 ELLA Y YO Aventura Featuring 1 UNIVERSAL (11O) on sales information compiled by Nielsen Don Omar 2 SONY BMG (39) SoundScan. Recaps for Hot Latin Songs 3 RAKATA Wisin & Yandel 3 EMM (10) are based on gross audience impressions 4 LLAME PA' VERTE Wisin & Yandel 4 INDEPENDENTS (13) from airplay monitored by Nielsen BDS. Ti- 5 VEN BAILALO Angel & Khriz 5 WEA (4) tles receive credit for sales or audience im- 6 MAYOR QUE YO Baby Ranks, pressions accumulated during each week Daddy Yankee, Tonny Tun Tun, Wisin, rh)I) Latin they appear on the pertinent chart. Yandel & Hector 7 CUENTALE Ivy Queen Recaps compiled by rock charts manager 8 NA NA NA (DULCE NINA) Pos. IMPRINT (Na Charted Titles) Anthony Colombo with assistance from A.B. Quintanilla III Presents 1 SONY BMG NORTE (33) Latin charts manager Ricardo Companioni. Kumbia Kings 2 EMI LATIN (8) 9 CONTRA VIENTO Y MAREA 3 EL CARTEL (2) mio Billboard, Flaco Jiménez is inducted into Intocable 4 DISA í77) the Hall of Fame, and Olga Tañón receives the 10 ESO EHH II Alexis & Fido 5 FONOVISA (25) I1O1 Latin ( (If' í\rtisls Spirit of Hope award. 11 LA TORTURA Memorably, Ricky Martin performs "Livin' Pos. -

1 Reggaetón: Pleasure, Perreo, and Puerto Rico an Accumulation Of

1 Reggaetón: Pleasure, Perreo, and Puerto Rico An accumulation of American hip hop, Latin American culture, and Caribbean style, reggaetón is a modern music style combining rapping and singing that arose in 1990s Puerto Rico. In a purgatory between a medium that externalizes misogynistic perceptions of women and a medium in which women can experience power through the reinvention of their sexuality, reggaetón’s identity is a topic of controversy in Puerto Rican popular culture today. The first perspective views reggaetón as a medium that sexually oppresses women through its lyrics and associated dance styles, contributing to Puerto Rico’s preexisting misogynistic culture. Direct lyrics from male reggaetón artists as well as academic articles, will provide a direct lens into the impact of the sexist nature of reggaetón. The second perspective considers reggaetón, specifically for female artists, as a zone for women to employ power through their sexuality. Ivy Queen is a case study that is exemplary for the second perspective. Considering both perspectives relative to one another provides insight into the consequences of reggaetón in contemporary Puerto Rico. To understand the cultural significance reggaetón has in contributing to gender inequality, it is first essential to consider the historical implications of sexuality and race in Puerto Rico. When colonized by the Spanish, a majority of the indigenous population was wiped out by disease and forced labor, instigating the mass influx of African slavery. Black female slaves were often the victims of sexual assault and violent rape by white slave owners. Thus, there existed an inherent sexualization of darker-skinned women by Spanish colonizers because their “darker-hued black female body [suggested] a 'natural' propensity for exotic sexual labor” (Herrera 44). -

Music 103 Syllabus

MUS 103: HIP HOP SEMESTER/YEAR???? ?? Shepard Hall Prof. Chadwick Jenkins ([email protected]) Days/Times Office: 78B Shepard Hall; Phone: X7666 Office Hours: ?? Course Objectives: This course will explore the history of hip hop from the earliest formations of the genre in the 1970s to the current moment. This course will have four primary areas of emphasis. First, although we will be interested in other elements of hip hop culture (including dancing, graffiti, literature, etc.), our primary focus will be on the music (the DJ, MC, and production techniques that go into producing hip hop tracks and albums). Second, this class will emphasize the development of the business and promotional aspects of hip hop. Hip hop has become a major business venture for recording studios, record labels, fashion venues, etc. and has had a huge impact on Black and White business in the US. Third, we will devote a large portion of our time to the developing technologies surrounding hip hop including turn tables, drum machines, MPCs, etc. Fourth and finally, we will explore the cultural and political impact hip hop has had on representations of Blackness, political views of violence and equity, and constructions of gender, race, and authenticity. Thus, this class will contribute to the following Departmental Learning Outcomes: 1) Outline major periods in the development of hip hop and recall key facts, writers, performers, technological advances, producers, and ideas; 2) Identify the technological developments contributing to hip hop, the business of hip hop production, and the impact hip hop has had on the social and political life of the US and beyond; 3) Identify different genres, performers, and musical styles through listening; 4) Demonstrate proficiency in writing about key concepts in hip hop history with a focus on descriptive writing (accounting for the sounds of the musical tracks and not just the lyrics, history, and biographical background). -

Ivy Queen FAN TV

Presents IVY QUEEN Ivy Queen (born Martha Ivelisse Pesante on March 4, 1972 in Añasco, Puerto Rico) is a composer and singer known as “La Diva”, “La Gata”, “La Caballota”, and “La Reina del Reggaeton”, At a young age Ivy’s parents “The Queen of Reggaeton”. moved to New York where she Ivy’s third album “Diva”, was was raised. When she was in her released in 2003. The songs teens, her parents returned to were originally written by their hometown, Añasco. Ivy her and performed with the went to school and graduated participation of various from high school. artists. When Ivy was 18, she moved to San Juan and met rapper and producer, DJ Negro. DJ Negro helped her and introduced her to a group called “Noise”. With “Noise” she wrote and performed her first song “Somos Rapperos Pero No Delincuentes” (We’re Rappers, Not Delincuents). Soon, DJ Negro convinced Ivy to go “solo” and in 1997, she made her debut with the recording of the album “En Mi Imperio” (In My Empire) for the Sony International Records label which sold over 100,000 copies. In the same year, Ivy traveled to Panama where she represented Puerto Rico in “The Battle of Rap”. She also did some presentations in the Dominican Republic, which were all “sold out” and later that year, she participated in “The First National Festival of Rap and Reggae”. There, Ivy was proclaimed the “Rap Singer of the Year”. Also, in 1997, Ivy was awarded the “Artista ‘97” award, naming her “The Peoples Favorite Rap Singer”, by Artista magazine. -

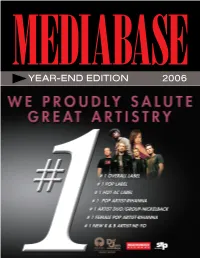

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

Redefining Mainstream: Effects of Contemporaneous Reggaeton Analysis

UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO PREPARATORIA BILINGÜE Redefining mainstream: effects of contemporaneous Reggaeton analysis. THESIS TO OBTAIN THE CREDIT OF SCIENTIFIC THOUGHT PRESENTS: IXIM QUITZE SALINAS AGUIRRE COUNSELOR: Q.F.B. MARCO ANTONIO RAMÍREZ PORRAS 1 CONTENT ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 5 JUSTIFICATION OF THE INVESTIGATION ............................................... 7 Research: .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives: ....................................................................................................................................... 7 General objective: ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Specific objective: ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Hypothesis: ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Main hypothesis: ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Alternative hypothesis: ............................................................................................................................. -

My New Updated 2012 List. All Types of Latin Music, Including Merengue, Merengue House, Latin Dance and More!

My new updated 2012 list. All types of Latin music, including Merengue, Merengue House, Latin Dance and more! Tropical Latin January 2012 Tropical Latin March 2012 1 Lovumba/ Daddy Yankee 1 Las Cosas Pequeñas/ Prince Royce 2 Me Toca Celebrar/ Tito \ "El Bambino\ " 2 Mi Santa/ Romeo Santos f./ Tomatito 3 Bebe Bonita/ Chino Y Nacho f./ Jay Sean 3 Mi Reto/ Luis Enrique 4 Por Nada/ Henry Santos 4 Solo Con Un Beso/ Jerry Rivera 5 Aires De Navidad/ N\ 'Klabe 5 Vallenato En Karaoke/ Elvis Crespo f./ Los Del 6 Aires De Navidad/ Remix/ N\ 'Klabe f./ Sergio Vargas Puente 7 Papi/ Original Radio/ Jennifer López 6 Me Voy De La Casa/ Tito \ "El Bambino\ " 8 All My Life/ Migz 7 Hotel Nacional/ Gloria Estefan 9 Energía/ Remix/ Alexis & Fido f./ Wisin & Yandel 8 Lindísima/ Grupomanía f./ Zone D\' Tambora 10 Me Gusta Tanto/ Mambo Remix/ Paulina Rubio f./ 9 International Love/ Pitbull f./ Chris Brown Gocho 10 Claridad/ Richy Peña Merengue/ Mambo Remix/ 11 I Like How It Feels/ Enrique Iglesias f./ Pitbull Luis Fonsi 12 Ya No Quiero Tu Querer/ José Alberto \ "El 11 Quédate Conmigo/ Zacarías Ferreira Canario\ " & Raulín Rosendo 12 Dilema/ Fabián 13 Toma Mi Vida/ Milly Quezada f./ Juan Luis Guerra 13 Ni Loca/ DJ Chino/ Merengue Pop Remix/ Fanny Lú 14 Amor En La Luna/ Ephrem J 14 Tengo Ganas/ Remix/ Ambar f./ El Cata 15 No La Quiero Perder/ Maffio Alkattraks Remix/ 808 15 No Apagues La Luz/ Jco (Ocho Cero Ocho) 16 Que Joyitas!/ Limi-T 21 16 Antes Solías/ Arcángel \ 'La Maravilla\ ' 17 Adiós/ D\'Mingo 17 El Pum/ Radio Edit/ Kalimete 18 Buscando Corazon/ Grupo -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

“Orgulloso De Mi Caserío Y De Quien Soy”: Race, Place, and Space in Puerto Rican Reggaetón by Petra Raquel Rivera a Disser

“Orgulloso de mi Caserío y de Quien Soy”: Race, Place, and Space in Puerto Rican Reggaetón By Petra Raquel Rivera A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Percy C. Hintzen, Chair Professor Leigh Raiford Professor Joceylne Guilbault Spring 2010 “Orgulloso de mi Caserío y de Quien Soy”: Race, Place, and Space in Puerto Rican Reggaetón © 2010 By Petra Raquel Rivera Abstract “Orgulloso de mi Caserío y de Quien Soy”: Race, Place, and Space in Puerto Rican Reggaetón by Petra Raquel Rivera Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Percy C. Hintzen, Chair My dissertation examines entanglements of race, place, gender, and class in Puerto Rican reggaetón. Based on ethnographic and archival research in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and in New York, New York, I argue that Puerto Rican youth engage with an African diasporic space via their participation in the popular music reggaetón. By African diasporic space, I refer to the process by which local groups incorporate diasporic resources such as cultural practices or icons from other sites in the African diaspora into new expressions of blackness that respond to their localized experiences of racial exclusion. Participation in African diasporic space not only facilitates cultural exchange across different African diasporic sites, but it also exposes local communities in these sites to new understandings and expressions of blackness from other places. As one manifestation of these processes in Puerto Rico, reggaetón refutes the hegemonic construction of Puerto Rican national identity as a “racial democracy.” Similar to countries such as Brazil and Cuba, the discourse of racial democracy in Puerto Rico posits that Puerto Ricans are descendents of European, African, and indigenous ancestors. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri