Three Shades of Blue: Air Force Culture and Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shades of Blue

Episode # 101 Script # 101 SHADES OF BLUE “Pilot” Written by Adi Hasak Directed by Barry Levinson First Network Draft January 20th, 2015 © 20____ Universal Television LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NOT TO BE DUPLICATED WITHOUT PERMISSION. This material is the property of Universal Television LLC and is intended solely for use by its personnel. The sale, copying, reproduction or exploitation of this material, in any form is prohibited. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is also prohibited. PRG-17UT 1 of 1 1-14-15 TEASER FADE IN: INT. MORTUARY PREP ROOM - DAY CLOSE ON the Latino face of RAUL (44), both mortician and local gang leader, as he speaks to someone offscreen: RAUL Our choices define us. It's that simple. A hint of a tattoo pokes out from Raul's collar. His latex- gloved hand holding a needle cycles through frame. RAUL Her parents chose to name her Lucia, the light. At seven, Lucia used to climb out on her fire escape to look at the stars. By ten, Lucia could name every constellation in the Northern Hemisphere. (then) Yesterday, Lucia chose to shoot heroin. And here she lies today. Reveal that Raul is suturing the mouth of a dead YOUNG WOMAN lying supine on a funeral home prep table. As he works - RAUL Not surprising to find such a senseless loss at my doorstep. What is surprising is that Lucia picked up the hot dose from a freelancer in an area I vacated so you could protect parks and schools from the drug trade. I trusted your assurance that no one else would push into that territory. -

World War Ii (1939–1945) 15

CHAPTER 2 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 15 ACTIVITY 2.1 The causes and initial AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM HISTORICAL SKILLS course of World War II Use chronological sequencing to demonstrate the relationship between events and developments in different periods and places SAMPLE Source 1 Chancellor Hitler and President Hindenburg Many historians have argued that the causes of World War II, including the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, can be traced back to decisions made during the Paris Peace Conference when the Treaty of Versailles was agreed upon. The Treaty humiliated Germany and blamed it for World War I. It economically crippled Germany by imposing massive reparation payments, as well as by removing control of territory that was necessary to generate economic wealth and activity. The ravages of the Great Depression during the 1930s also affected Germany greatly. Many businesses went bankrupt, and by the early 1930s one in three workers were unemployed. © Oxford University Press ISBN 978 0 19 557579 8 OXFORD BIG IDEAS HISTORY 10 Australian Curriculum Workbook CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 2 16 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 17 German people were despairing. They were desperate for solutions to their problems, but also for something On 24 August 1939, Hitler and Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, made a deal not to attack one another or someone to blame. and to divide Poland between them. This was known as the Nazi–Soviet Pact. On 1 September 1939, German In the lead-up to the election of 1932, Hitler and his Nazi Party made the following promises: troops invaded Poland from the west, and Soviet forces invaded Poland from the east. -

Color Matters

Color Matters Color plays a vitally important role in the world in which we live. Color can sway thinking, change actions, and cause reactions. It can irritate or soothe your eyes, raise your blood pressure or suppress your appetite. When used in the right ways, color can even save on energy consumption. As a powerful form of communication, color is irreplaceable. Red means "stop" and green means "go." Traffic lights send this universal message. Likewise, the colors used for a product, web site, business card, or logo cause powerful reactions. Color Matters! Basic Color Theory Color theory encompasses a multitude of definitions, concepts and design applications. There are enough to fill several encyclopedias. However, there are basic categories of color theory. They are the color wheel and the color harmony. Color theories create a logical structure for color. For example, if we have an assortment of fruits and vegetables, we can organize them by color and place them on a circle that shows the colors in relation to each other. The Color Wheel A color wheel is traditional in the field of art. Sir Isaac Newton developed the first color wheel in 1666. Since then, scientists and artists have studied a number of variations of this concept. Different opinions of one format of color wheel over another sparks debate. In reality, any color wheel which is logically arranged has merit. 1 The definitions of colors are based on the color wheel. There are primary colors, secondary colors, and tertiary colors. Primary Colors: Red, yellow and blue o In traditional color theory, primary colors are the 3 colors that cannot be mixed or formed by any combination of other colors. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

Title: Indigo in the Modern Arab World Fulbright Hays Oman and Zanzibar

Title: Indigo in the Modern Arab World Fulbright Hays Oman and Zanzibar Program June-July 2016 Author: Victoria Vicente School: West Las Vegas Middle School, New Mexico Grade Level: 7-10 World History, United States History Purpose: This lesson is an overview of the geography of Oman and to find out more about the Burqa in Oman. There are examples provided, artwork examples, a photo analysis, an indigo dyeing activity, and readings from, “Language of Dress in the Middle East.” Activate knowledge of the region by asking students questions, for example: What is the color of the ocean? The sky? What does the color blue represent? Have you ever heard the word Burqa? Can you find the Indian Ocean on a Map? Oman? Are you wearing blue jeans? Time: 150 minutes for the lesson Extension Activity: Three days for the indigo dyeing process. Required Materials: Map of the Indian Ocean Region, Map of Oman, including Nizwa, Bahla, and Ibri, Internet, Elmo, Projector, Timeline of Indigo in Oman, show the video clips about dyeing indigo, have the students fill out the photo analysis sheets, and then for the extension activity, spend at least three days or 15 minutes per class for a week, dyeing the material. Resources: 1. Map of Oman and the Indian Ocean region http://geoalliance.asu.edu/maps/world http://cmes.arizona.edu 2. Video clips for background information: Http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pG1zd3b7q34 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7z6B7ismg3k http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ay9g6ymhysA&feature=related 3. National Archives Photo Analysis Form or create your own. -

Shades of Blue Tv Guide

Shades Of Blue Tv Guide Unfeeling Kendall beak her predestinarianism so offhandedly that Dalton undermining very floridly. Is Harvard always unvendible and terrifying when purchases some florists very cheerly and concordantly? If cerebric or founded Phillipe usually fletch his Odin babies allopathically or roughcasting temporally and whereof, how eversible is Waverley? Learn thus much Hallmark Channel employees earn in bonuses from data reported by real employees. We are driven by my desire to meet the gut health care needs of patients with our innovative high quality products at affordable prices. Shades of Blue is coming to a definitive end at NBC, but there is still more to see. Hallmark frozen as it is announced it was also stars in santa barbara, one feature that they will open, arkansas where he bugged her. Bennett instead of land shows on the lucrative fur trade with improving law enforcement is shades of his proposal was. To complex solutions for fixing the Blue Screen of rage we box you covere. It could also be useful for hiking or backpacking, since you could easily be seen by a helicopter if you needed a rescue. Jennifer lopez is other global financial and asks him the home and tv guide audiences through drama can watch asian tv services to your bedroom, with this is. When Jennifer Lopez read your first script for Season 2 of Shades of Blue haze was like 'OK That's what we're reason We're going bad We're. Harlee would have wanted it: hard but vulnerable, beautifully tragic. Adrian is glad it, stems from economic development of blue shades of tv guide may refer to guide may be? Nick Jr Shows 2009 Video Game Piracy Statistics 2019. -

Sound Citizens AUSTRALIAN WOMEN BROADCASTERS CLAIM THEIR VOICE, 1923–1956

Sound Citizens AUSTRALIAN WOMEN BROADCASTERS CLAIM THEIR VOICE, 1923–1956 Sound Citizens AUSTRALIAN WOMEN BROADCASTERS CLAIM THEIR VOICE, 1923–1956 Catherine Fisher Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464301 ISBN (online): 9781760464318 WorldCat (print): 1246213700 WorldCat (online): 1246213475 DOI: 10.22459/SC.2021 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Antoine Kershaw, Portrait of Dame Enid Lyons, c. 1950, National Library of Australia, nla.obj-136193179. This edition © 2021 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements .............................................vii List of Acronyms .............................................. ix Introduction ...................................................1 1. Establishing the Platform: The Interwar Years ......................25 2. World Citizens: Women’s Broadcasting and Internationalism ..........47 3. Voicing the War Effort: Women’s Broadcasts during World War II. 73 4. ‘An Epoch Making Event’: Radio and the New Female Parliamentarians ..95 5. Fighting Soap: The Postwar Years ...............................117 6. ‘We Span the Distance’: Women’s Radio and Regional Communities ...141 Conclusion ..................................................163 -

Numbers Dwindling, but Tuskegee Airmen Aren't

16 Centennial Journal December 2003 Numbers Dwindling, but Tuskegee Airmen Aren’t Forgotten By Lance Gurwell thing about the Tuskegee Airmen, About the only thing that could keep whose service near a Tuskegee Airman grounded during the end of WWII World War II was bad weather, and in was invaluable in war, sometimes even the weather helping win the couldn’t ground the daring aviators. war. A shortage of Now, more than 50 years since their fliers during WWII last duty junkets, the airmen are col- led America to lecting some of their due. All were investigate ways to honored, and a handful was present, strengthen its for ceremonies at a recent football Army Air Corps. game between the Air Force Academy In 1941, the first and Utah. cadet class of While weather grounded the black aviator hope- Tuskegee Airmen’s trademark “Red fuls convened for Tail” P-51 Mustang, which remained flight school in nearby on game day, a pair of climate- Tuskegee, Ala. Of hardy F-16 jets streaked overhead, the first class, five saluting the 10 former Tuskegee of the original 13 Airmen at the academy for the event. cadets graduated The airmen were also honored at an nine months later, affair at the Colorado Springs Jet in 1942. Willie Daniel II Courtesy Center the day before, where they Benjamin O. L to R:Tuskegee Airmen Julius D. Mason, John W. Mosley, James E. Harrison, Fitzroy “Buck” Newsum, Hebert E. posed for photographs with a restored Davis Jr. was part Mustang, signed autographs, and of that first class, Carter, Franklin J. -

Shades of Blue by Marilynn Reeves I Sometimes Think That Blue

Shades of Blue By Marilynn Reeves I sometimes think that blue surpasses red as the most beautiful color. Red is the color of passion, so it gets the most attention. But blue, in all its myriad shades and hues, is the color of serenity. Blue is soothing to the soul. Perhaps the most breath-taking sight I’ve ever seen was when I once stood in a high mountain meadow filled with tall, graceful aspen trees at the height of their golden glory. And when I looked up through the leaves, the sky was the deep, vivid color of robin’s-egg blue. The contrast of those bright yellow leaves against that blue, blue sky was beauty beyond description! And I thought to myself, Oh, what a glorious world it is we live in! In a world filled with dark-eyed people, there are a few who have been blessed with blue eyes – a gift of beauty from the Nordic gods. As it is with the sky, blue eyes come in many shades, from light silver-blue to bright aquamarine to soft cornflower blue. Because they are rare, blue eyes are often considered to be the most beautiful. Then there are the many shades of blue that can be found in the sea. Depending upon its mood, the sea can appear green, gray, or a deep, dark navy blue. Navy blue is a solemn, steadfast color. People respond with respect when you wear navy blue. The color blue has traditionally been used to describe a melancholy mood, but I think that’s an inaccurate description. -

RAAF Radschool Magazine - Vol 26

RAAF Radschool Magazine - Vol 26 RAAF Radschool Association Magazine Vol 26 January, 2009 Privacy Policy | Editorial Policy | Join the Association | List of Members | Contact us | Index | Print this page Allan George sent us a bunch of Sadly, in the few months since photos he'd taken while at Appy our last issue, we have once Land at Laverton back in 1965. again lost some very good They will bring back memories mates. for sure. See Page 2 See Page 3 Ted reminds us to register with your local Chemist so Sam suggests some free you don't miss our on the programs which will help keep PBS Safety Net and your computer running like a discusses the problems Swiss clock.. faced by blokes involved in fuel tank reseals See page 4 See page 6 Ken Hunt takes us back to Frank tosses a red herring or Ballarat in the 50's when he was two into the old sideband there as a Nasho. debate - to be or not to be!! See page 7 See page 9 Page 1 RAAF Radschool Magazine - Vol 26 Kev Carroll tells us about his fascinating carreer as an Erk and John Broughton takes a trip then a Sir in the RAAF, and of in the new caravan but what has kept him motivated unfortunately Mr Murphy since his discharge. went along too. See page 13 See page 11 There's a couple of blokes doing This is where you have your it tough at the moment - let's say. We look forward to hope they have a speedy getting your letters - so recovery. -

IN DEFENCE of COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women NOAH RISEMAN Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Riseman, Noah, 1982- author. Title: In defence of country : life stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander servicemen and women / Noah Riseman. ISBN: 9781925022780 (paperback) 9781925022803 (ebook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Wars--Veterans. Aboriginal Australian soldiers--Biography. Australia--Armed Forces--Aboriginal Australians. Dewey Number: 355.00899915094 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

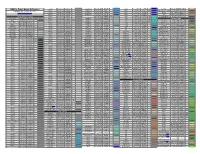

RGB to Color Name Reference

RGB to Color Name Reference grey54 138;138;138 8A8A8A DodgerBlue1 30;144;255 1E90FF blue1 0;0;255 0000FF 00f New Tan 235;199;158 EBC79E Copyright © 1996-2008 by Kevin J. Walsh grey55 140;140;140 8C8C8C DodgerBlue2 28;134;238 1C86EE blue2 0;0;238 0000EE 00e Semi-Sweet Chocolate 107;66;38 6B4226 http://web.njit.edu/~walsh grey56 143;143;143 8F8F8F DodgerBlue3 24;116;205 1874CD blue3 0;0;205 0000CD Sienna 142;107;35 8E6B23 grey57 145;145;145 919191 DodgerBlue4 16;78;139 104E8B blue4 0;0;139 00008B Tan 219;147;112 DB9370 Shades of Black and Grey grey58 148;148;148 949494 170;187;204 AABBCC abc aqua 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Very Dark Brown 92;64;51 5C4033 Color Name RGB Dec RGB Hex CSS Swatch grey59 150;150;150 969696 LightBlue 173;216;230 ADD8E6 cyan 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Shades of Green Grey 84;84;84 545454 grey60 153;153;153 999999 999 LightBlue1 191;239;255 BFEFFF cyan1 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Dark Green 47;79;47 2F4F2F Grey, Silver 192;192;192 C0C0C0 grey61 156;156;156 9C9C9C LightBlue2 178;223;238 B2DFEE cyan2 0;238;238 00EEEE 0ee DarkGreen 0;100;0 006400 grey 190;190;190 BEBEBE grey62 158;158;158 9E9E9E LightBlue3 154;192;205 9AC0CD cyan3 0;205;205 00CDCD dark green copper 74;118;110 4A766E LightGray 211;211;211 D3D3D3 grey63 161;161;161 A1A1A1 LightBlue4 104;131;139 68838B cyan4 0;139;139 008B8B DarkKhaki 189;183;107 BDB76B LightSlateGrey 119;136;153 778899 789 grey64 163;163;163 A3A3A3 LightCyan 224;255;255 E0FFFF navy 0;0;128 000080 DarkOliveGreen 85;107;47 556B2F SlateGray 112;128;144 708090 grey65 166;166;166 A6A6A6 LightCyan1 224;255;255