No Dean Left Behind I Want to Thank You All for Being Here This Afternoon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

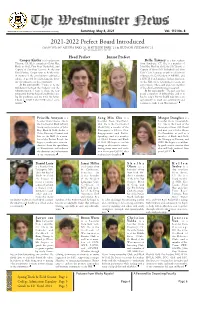

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

Beemok Dean Profile College of Charleston School of Education

Beemok Dean Profile College of Charleston School of Education 1 | COLLEGE OF CHARLESTON May 2021 THE OPPORTUNITY The College of Charleston cordially invites nominations and applications for the position of Beemok Dean of the School of Education. The dean Twill collaborate with the provost, faculty and others in developing and implementing the School of Education’s strategic plan to achieve institutional goals and objectives; will serve as a key strategic partner in enhancing the profile and prominence of the School; and will oversee the staffing and operation of all units within the School to ensure its effectiveness and efficiency. The College of Charleston, founded in 1770, is the oldest university south of Virginia and the 13th oldest in the United States. The College is a public liberal arts and sciences university overseen by a 20-member Board of Trustees, which delegates the administration of the campus to the president. A state-supported institution, which joined South Carolina’s public university system in 1970, the College of Charleston provides a world-class education in the arts, humanities, sciences, languages, education and business, retaining a strong liberal arts and sciences interdisciplinary undergraduate curriculum. The College is organized into several schools: the School of the Arts; the School of Business; the School of Education, Health, and Human Performance; the School of Humanities and Social Sciences; the School of Languages, Cultures, and World Affairs; the School of Sciences and Mathematics; the Honors College; and the Graduate School (also known as the University of Charleston, S.C.). In fall 2020, the College admitted students to a newly established systems engineering program – another example of the College striving to meet the growing educational demands of the state, region and country. -

SENIOR MANAGEMENT CHART As at September 2021

SENIOR MANAGEMENT CHART as at September 2021 Mr Damien Farrell Professor Abid Khan Vice-President Deputy Vice-Chancellor Professor Margaret Gardner (Advancement) (Global Engagement) & President & Vice-Chancellor Vice-President Ms Emily Spencer Chief of Staff & Executive Director, Dr Cecilia Hewlett* Office of the Vice-Chancellor Pro Vice-Chancellor (Prato Centre & Global Network Development) Professor Professor Professor Professor Ken Sloan Mr Peter Marshall Mr Leigh Petschel Rebekah Brown Sharon Pickering Susan Elliott Deputy Vice-Chancellor Chief Operating Officer Chief Financial Officer Deputy Vice-Chancellor Deputy Vice-Chancellor Provost & & Senior Vice-President & Senior Vice-President (Research) & (Education) & Senior Senior Vice-President & Senior Vice-President Senior Vice-President Vice-President Ms Renaye Peters Mr George Ou Professor Vice-President Professor Mike Ryan Professor Jacinta Elston Mrs Sarah Newton Executive Director, Matthew Gillespie Pro Vice-Chancellor Pro Vice-Chancellor Pro Vice-Chancellor (Campus Infrastructure Financial Resources Vice-Provost (Research) (Indigenous) (Enterprise) & Services) Management (Academic Affairs) Mr Bradley Williamson Professor Kris Ryan Professor Xinhua Wu Vacant Mr Bob Gerrity Executive Director, Executive Director, Pro Vice-Chancellor Pro Vice-Chancellor University Librarian Buildings & Property Corporate Finance (Academic) (Precinct Partnerships) Mr Vladimir Prpich Mr Donald Speagle Executive Director, Executive Director, Campus Community Faculty Deans International Campuses Group -

Start-Up Company Networking Event 31St March 2021 (Wednesday) 1800 – 2000 Online (MS Teams)

Start-up company networking event 31st March 2021 (Wednesday) 1800 – 2000 Online (MS Teams) IChemE start-up company networking event Aims: Event details: • Build a community of chem-eng- • Anticipated participants: related start-ups for sharing • 13 start-ups information and experience • 1 government grant expert • ~20 IChemE members (spectators) • Inspire students/researchers about the application of chem eng knowledge and possible career paths Schedule • 1800 – 1830: Introduction by start-up representatives • 3 min each (10 start-ups: CMCL Innovations / Manchester Biogel / Octeract / Carbon Sink LLC / Accelerated Materials / Dye Recycle / Olwg / Nanomox / Solveteq / Greenr) • 1830 – 1910: Talks by Professor Nigel Brandon, Mr Phil Caldwell & Dr David Hodgson • 10 min each --- > start-up journey + key learning points • 10 min Q & A for all three speakers • 1910 – 1930: Talk by Dr Mat Westergreen-Thorne • 10 min --- > application of government grants • 10 min Q & A • 1930 – 2000: Panel discussions • Topics: • Personal development for start-up founders with technical background • Early-stage development: common mistakes, major milestones, resources available • Website: https://www.rfcpower.com/ Prof. Nigel Brandon (Director & co-founder) • Founded: 2017 • Product: Novel hydrogen-manganese reversible fuel • https://www.imperial.ac.uk/people/n.brandon cell for grid scale energy storage. • Email: [email protected] • RFC Power specializes in developing novel flow • Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Chair in battery chemistries for energy storage systems. The Sustainable Development in Energy, Imperial College company was spun out from Imperial College’s London. Departments of Earth Science & Engineering and Chemistry in 2017, underpinned by a number of • BSc(Eng) in Minerals Technology and PhD in scientific breakthroughs and patents from the labs of electrochemical engineering from Imperial College Nigel Brandon, Anthony Kucernak, Javier Rubio Garcia London, followed by a 14 year research career in and Vladimir Yufit over the prior 8 years. -

Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences

________________________________________________________________ Position Specification Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences This Position Specification is intended to provide information about Montclair State University and the position of Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences. It is designed to assist qualified individuals in assessing their interest in this position. ________________________________________________________________ DIVISION OF HUMAN RESOURCES 150 Clove Road | Little Falls, NJ 07024 | 973-655-5293 The Opportunity The second largest university in New Jersey, Montclair State University is a nationally ranked Carnegie Research III Institution and ranked with the top 100 National Public Institutions of Higher Education by U.S. News and World Report. Montclair State is designated by New Jersey as one of four public research institutions. With over 21,000 students, the University is poised to enter its next period of transformative development, and is seeking a Dean to lead the College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHSS), one of the largest of the University’s eleven colleges and schools. The CHSS Dean is a key member of the University’s academic leadership team, expected to have a transformative role in shaping the future of Montclair State University. The College enrolls currently approximately 5,000 majors, 1,000 minors, and 700 graduate students in twenty-two undergraduate degree programs, eleven master’s degree programs, and two doctoral programs in Audiology and Clinical Psychology. An interdisciplinary, -

UMN SPH Position Profile Final for Posting.Docx

An invitation to apply for the position of Dean School of Public Health University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota THE SEARCH The University of Minnesota (UMN) seeks an innovative strategist to serve as the Dean of the School of Public Health (SPH or School). The COVID-19 pandemic has both emphasized the importance of public health and highlighted the negative consequences caused by health disparities and unequal access to healthcare. The next Dean will be poised to take advantage of the current moment for public health and work to elevate the School’s impact on the health and well being of the citizens of Minnesota, the nation, and beyond. The next Dean will inspire a vision for the School of Public Health as both a high-energy public health scholar-advocate and leader in the field, guiding the School in creating inventive solutions in its commitment to make health a human right. As one of the premier schools of public health in the world, the School of Public Health has prepared some of the most influential leaders in the field, transforming the way public health is practiced around the globe. The School has been recognized for its excellence in research and education and for advancing policies and practices that both create and sustain health equity. Consistently ranked in the top 10 by U.S. News and World Report, the School is ranked #2 for its Master of Healthcare Administration. The School also ranks #6 in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding among schools of public health, and its researchers receive more NIH funding than any other school of public health at a public university. -

Bylaws of the University of Connecticut School of Medicine1 Outline I. Preamble…………………………………………

Bylaws of the University of Connecticut School of Medicine1 Outline I. Preamble……………………………………………………………………….…………………2 II. Faculty………………………………………………………………………….…………………2 III. Administration………………………………………………………………….………….……..3 A. Dean………………………………………………………………………….……………….3 B. Chief Academic Officers………………………………………………………………...….4 C. Standing Administrative Committees…………………………………………………...…4 1. Admissions Committee……………………………………………………..…...…4 2. Senior Appointment and Promotions Committee……………………..…………5 3. Appeals Committees……………………………………………………………………5 4. Academic Advancement Committee………………………………………………….5 IV. Departments…………………………………………………………………………………...…6 V. Centers……………………………………………………………………………………………7 VI. Planning and Policy Development……………………………………………………………..9 A. Education Council……………………………………………………………………….…10 B. Research Council…………………………………………………………………….....…11 C. Clinical Council……………………………………………………………………………..11 D. Public Issues Council………………………………………………………………...……12 E. Dean’s Council……………………………………………………………………………..13 VII. Oversight Committee…………………………………………………………………………..15 VIII. Communication Regarding Governance…………………………..…………………………16 IX. Amendments to the Bylaws……………………………………………………………………17 X. Organizational Chart of Working Relationships……………………………………………..18 Appendices A. Guidelines for Appointment to Junior Faculty Rank and Joint Appointments….……………20 B. Guidelines for Appointment or Promotion to Senior Faculty Rank and/or Tenure………….26 C. Post-Tenure Review……………………………………………………………………………….42 D. Procedures for Departmental and Center Reviews……………………………………...…….46 -

Dean of the College of Education University of West Georgia

Inviting Applications and Nominations DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION University of West Georgia The DEAN OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION will build upon the strengths of the college’s academic programs, curate robust student-centric experiences, expand research and scholarly achievements, and engage the internal and external University community. Through visionary, inclusive, and entrepreneurial leadership, the Dean will work collaboratively with faculty, staff, and administrators and will report directly to the Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs. The University of West Georgia seeks a leader who will advance and support the University’s mission of fulfilling workforce development needs while contributing to the social, cultural, and economic development of the region, state, nation, and world. THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION The College of Education offers 6 bachelor’s, 4 minors, 17 master’s, 8 specialists, 3 doctoral, and a number of With one of the Southeast’s largest and most respected certificate, certification, and endorsement colleges of education, the University of West programs. It continues to be highly ranked among peer Georgia (UWG) prepares graduates for meaningful, institutions, including its recent ranking as #1 on the professional careers in three dynamic areas of focus: Best Value School list, and boasts many accreditations, (1) Teaching (Elementary, Special, Physical, and including ASHA and CACREP. Secondary Education and Reading Instruction); UWG’s College of Education has six departments: (2) Leadership (Sport Management, Educational (1) Educational Technology and Foundations, (2) Leadership, Higher Education Administration, Literacy and Special Education, (3) Sport Management, Media, and College Student Affairs); and (3) Wellness Wellness, and Physical Education, (4) Counseling, (Health and Community Wellness, Speech-Language Higher Education, and Speech-Language Pathology, (5) Pathology, and Professional Counseling). -

Ashish Vaidya, Ph.D., Dean of the Faculty Professor of Economics California State University Channel Islands

Ashish Vaidya, Ph.D., Dean of the Faculty Professor of Economics California State University Channel Islands Dr. Ashish Vaidya is Dean of the Faculty (2005-present) and Professor of Economics (2002- present) at California State University Channel Islands - the CSU system’s 23rd and newest campus. Previously he was the Director of the MBA Program (2003-2005) and the Founding Director of the Center for International Affairs (2004-2006). Prior to joining CI he was Professor of Economics and Statistics, and Associate Chair of the Department of Economics at Cal State Los Angeles (1991- 2002). He was the Director of MBA Programs (1997-2001) in the College of Business and Economics at Cal State Los Angeles. He joined Cal State Los Angeles in 1991 after completing his doctorate from the University of California at Davis. His fields of specialization are International Trade, Applied Microeconomics, and Development Economics and has taught courses in Business Strategy and Global Business. He has published research articles in the areas of Strategic and Optimal Trade Policy, Agricultural Policy, as well as pedagogical issues of business and management education in leading journals. Dr. Vaidya is the editor of the two-volume Globalization: An Encyclopedia of Trade, Labor, and Politics. As Dean of the Faculty he provides leadership for over 200 tenure-track and lecturer faculty, two schools (Business & Economics and Education), and 13 program areas, in support of excellence in teaching, research, creative activities, and service. He oversees a budget of $3 million in the Office of the Dean and $19 million in budgets of program areas, centers, and institutes. -

Dean, College of Liberal Arts

Dean, College of Liberal Arts The University of Massachusetts Boston invites applications for the position of Dean, College of Liberal Arts (CLA). The University The University of Massachusetts Boston (UMass Boston) is a recognized model of excellence for urban public research universities. The scenic waterfront campus, with easy access to downtown Boston, is located next to the John F. Kennedy Library and Presidential Museum, the Commonwealth Museum and Massachusetts State Archives, and the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate. One of the five campuses of the UMass system, UMass Boston is a research university with a teaching soul. It combines the rigorous focus on generation of knowledge that characterizes a major research university with a dedication to teaching that places its top scholars in undergraduate and graduate classrooms where a 17:1 student-to-faculty ratio fosters easy student-faculty interaction. Eighty-seven percent of full-time faculty hold the highest degree in their fields. UMass Boston has a growing reputation for innovation and a particular focus on research addressing complex urban issues. As metropolitan Boston’s only public research university, UMass Boston offers its diverse student population both an intimate learning environment and the rich experience of a great American city. The University maintains a strong commitment to all aspects of diversity and inclusion, including anti-racist and health promoting initiatives. Leadership Chancellor Marcelo Suárez-Orozco assumed the role of chancellor of the University of Massachusetts Boston on August 1, 2020. Prior to coming to UMass Boston Suárez-Orozco served as the inaugural UCLA Wasserman Dean, leading two academic departments, 16 nationally renowned research institutes, and two innovative demonstration schools at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education & Information Studies. -

Dean of the School of Education DEAN of the SCHOOL of EDUCATION

SAINT MARY’S UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Dean of the School of Education DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION The School of Education is a professional school that United Kingdom at the University of Birmingham. offers three undergraduate majors/minors, fourteen Further, the Dean will create greater pathways for the graduate degrees, and specialized certificate options. School to collaborate with both the Catholic schools With 200 undergraduate students and over 1,500 and public schools from K-12. The Dean will also graduate and professional program students, including find ways to work with and support Charter School a number of bachelor’s completion students, both in Education, particularly those within the Character classroom and online settings, the school prepares Education environment. highly effective teachers, skilled, principled graduates who consistently lead in the world of elementary, In addition, the Dean will assess the programmatic secondary, ESL, reading, and special education, as well landscape of the school, evaluating and enhancing as in education administration. A significant strength its offerings to meet the demands of the education of the school is its partnership with Wiley Educational community while also integrating grant opportunities Services to develop and deliver a growing catalog of related to Character Education. The Dean should online degree programs. lead with a spirit of innovation in identifying new audiences, content, and modes of delivery that meet The School of Education is one of five schools within the needs of those audiences, including online the University. Reporting to the Provost and Dean learning and its application to undergraduate and of Faculties, this position will lead a number of key graduate professional programs and certifications. -

University Officers, Dean Chairs and Academic Administrators Listing

The Farmer School of Business Aerospace Studies Executive Officers of Matthew B. Myers (2014) Allison Galford, Lt. Colonel, USAF (2016) Professor, Marketing B.S., United Air Force Academy, 1998; M.S., Administration B.A., University of Louisville, 1986; M.B.A., George Mason University, 2006. University of South Carolina, 1992; PhD., Gregory P. Crawford (2016) Michigan State University, 1997. Anthropology President; Professor, Physics Mark Peterson (2003) B.S, Kent State, 1987; M.A., 1988; Ph.D., 1991. College of Education, Health and Society Professor, Anthropology Michael Dantley (2015) B.A., University of California-Los Angeles, Phyllis Callahan (1988) Professor, Educational Leadership 1984; M.A, Catholic University of America, Provost and Executive Vice President for B.A., University of Pennsylvania, 1972; M.Ed., 1989; Ph.D., Brown University, 1996. Academic Affairs; Professor, Biology Miami University, 1976; Ph.D., University of B.S., Fairleigh Dickinson 1974; M.S., 1981; Cincinnati, 1986. Architecture and Interior Design Ph.D., Rutgers, 1986. Mary Rogero (2008) (Interim) College of Engineering and Computing Associate Professor, Architecture & Interior David K. Creamer (2008) Marek Dollár (2000) Design Vice President for Finance and Business Professor, Engineering Science B.F.A., Wright State Univ.-Lake Campus, Services and Treasurer B.S., Stanislaw Staszic (Poland), 1974; M.S., 1984; M.Arch., Miami University, 1989. B.B.A., Ohio, 1976; M.S., Kent State, 1986; 1975; Ph.D., 1981. Ph.D., 1990. Art College of Creative Arts Thomas Effler (2016) (Interim) J. Peter Natale (2013) Elizabeth Mullenix (2006) Professor, Art Vice President for Information Technology Professor, Theatre B.S., Cincinnati, 1972; M.F.A., Indiana, 1977.