The Lion's Mane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serengeti National Park

Serengeti • National Park A Guide Published by Tanzania National Parks Illustrated by Eliot Noyes ~~J /?ookH<~t:t;~ 2:J . /1.). lf31 SERENGETI NATIONAL PARK A Guide to your increased enjoyment As the Serengeti National Park is nearly as big as Kuwait or Northern Ireland no-one, in a single visit, can hope to see Introduction more than a small part of it. If time is limited a trip round The Serengeti National Park covers a very large area : the Seronera valley, with opportunities to see lion and leopard, 13,000 square kilometres of country stretching from the edge is probably the most enjoyable. of the Ngorongoro Conservation Unit in the south to the Kenya border in the north, and from the shores of Lake Victoria in the If more time is available journeys can be made farther afield, west to the Loliondo Game Controlled Area in the east. depending upon the season of the year and the whereabouts of The name "Serengeti" is derived from the Maasai language the wildlife. but has undergone various changes. In Maasai the name would be "Siringet" meaning "an extended area" but English has Visitors are welcome to get out of their cars in open areas, but replaced the i's with e's and Swahili has added a final i. should not do so near thick cover, as potentially dangerous For all its size, the Serengeti is not, of itself, a complete animals may be nearby. ecological unit, despite efforts of conservationists to make it so. Much of the wildlife· which inhabits the area moves freely across Please remember that travelling in the Park between the hours the Park boundaries at certain seasons of the year in search of 7 p.m. -

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brandоаlionоаsuede Desert Poncho

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 Free Knitting Pattern from Lion Brand Yarn Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 SKILL LEVEL: Intermediate (Level 3) SIZE: Small, Medium, Large Width 10 (10½, 11)" [25.5 (26.5, 28) cm] at neck; 60 ½ (64, 68½)" [153.5 (162.5, 174) cm] at lower edge Length 23 (25½, 28)" [58.5 (65, 71) cm] at sides; 30 (32 ½, 35)" [76 (82.5, 89) cm] at points Note: Pattern is written for smallest size with changes for larger sizes in parentheses. When only one number is given, it applies to all sizes. To follow pattern more easily, circle all numbers pertaining to your size before beginning. CORRECTIONS: None as of Jun 30, 2016. To check for later updates, click here. MATERIALS • 210126 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Coffee 6 (6, 7) Balls (A) • 210125 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Mocha *Lion® Suede (Article #210). 100% Polyester; package size: Solids: 3.00 3 (4, 4) Balls (B) oz./85g; 122 yd/110m balls • 210098 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Ecru Prints: 3:00 oz/85g; 111 yd/100m balls 3 (4, 4) Balls (C) • Lion Brand Crochet Hook Size H8 (5 mm) • Lion Brand Split Ring Stitch Markers • Additional Materials • Size 8 [5 mm] 24" [60 cm] circular needles • Size 8 [5 mm] 40" [100 cm] circular needles or size needed to obtain gauge • Size 6 [4 mm] 16" [40 cm] circular needles GAUGE: 14 sts + 23 rnds = 4" [10 cm] in Stockinette st (knit every rnd) on larger needle. -

Serengeti: Nature's Living Laboratory Transcript

Serengeti: Nature’s Living Laboratory Transcript Short Film [crickets] [footsteps] [cymbal plays] [chime] [music plays] [TONY SINCLAIR:] I arrived as an undergraduate. This was the beginning of July of 1965. I got a lift down from Nairobi with the chief park warden. Next day, one of the drivers picked me up and took me out on a 3-day trip around the Serengeti to measure the rain gauges. And in that 3 days, I got to see the whole park, and I was blown away. [music plays] I of course grew up in East Africa, so I’d seen various parks, but there was nothing that came anywhere close to this place. Serengeti, I think, epitomizes Africa because it has everything, but grander, but louder, but smellier. [music plays] It’s just more of everything. [music plays] What struck me most was not just the huge numbers of antelopes, and the wildebeest in particular, but the diversity of habitats, from plains to mountains, forests and the hills, the rivers, and all the other species. The booming of the lions in the distance, the moaning of the hyenas. Why was the Serengeti the way it was? I realized I was going to spend the rest of my life looking at that. [NARRATOR:] Little did he know, but Tony had arrived in the Serengeti during a period of dramatic change. The transformation it would soon undergo would make this wilderness a living laboratory for understanding not only the Serengeti, but how ecosystems operate across the planet. This is the story of how the Serengeti showed us how nature works. -

Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus Oryx) Meat Composition on Its Further Technological Processing

CZECH UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES PRAGUE Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences Department of Animal Science and Food Processing Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing DISSERTATION THESIS Prague 2018 Author: Supervisor: Ing. et Ing. Petr Kolbábek prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová, CSc. Co-supervisors: Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D. Declaration I hereby declare that I have done this thesis entitled “Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing” independently, all texts in this thesis are original, and all the sources have been quoted and acknowledged by means of complete references and according to Citation rules of the FTA. In Prague 5th October 2018 ………..………………… Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová CSc., Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. and Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D., and doc. Ing. Lenka Kouřimská, Ph.D., my research supervisors, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work. I am very gratefull to Ing. Petra Maxová and Ing. Eva Kůtová for their valuable help during the research. I am also gratefull to Mr. Petr Beluš, who works as a keeper of elands in Lány, Mrs. Blanka Dvořáková, technician in the laboratory of meat science. My deep acknowledgement belongs to Ing. Radek Stibor and Mr. Josef Hora, skilled butchers from the slaughterhouse in Prague – Uhříněves and to JUDr. Pavel Jirkovský, expert marksman, who shot the animals. I am very gratefull to the experts from the Natura Food Additives, joint-stock company and from the Alimpex-maso, Inc. -

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (Revised 3/15/19)

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (revised 3/15/19) Every effort will be made to update this list on a seasonal basis. List subject to change without notice due to ongoing Zoo improvements or animal care. North American Wetlands: Muted Swans Mallard Duck Wild Turkey (off Exhibit) Egyptian Goose American White pelican (located in flamingo exhibit during winter months) Bald Eagle Wild Way Trail: (seasonal) Red-necked wallaby Prehensile tail porcupine Ring-tailed lemur Howler Monkey Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Red’s Hobby Farm: Domestic goats Domestic sheep Chickens Pied Crow Common Barn Owl Budgerigar (seasonal) Bali Mynah (seasonal) Crested Wood Partridge (seasonal) Nicobar Pigeon (seasonal) John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Frogs: Smokey Jungle frogs Chacoan Horned frog Tiger-legged monkey frog Vietnamese Mossy frog Mission Golden-eyed Tree frog Golden Poison dart frog American bullfrog Multiple species of poison dart frog North America: Golden Eagle North American River Otter Painted turtle Blanding’s turtle Common Map turtle Eastern Box turtle Red-eared slider Snapping turtle Canada Lynx Brown Bear Mountain Lion/Cougar Snow Leopard South America: South American tapir Crested screamer Maned Wolf Chilean Flamingo Fulvous Whistling Duck Chiloe Wigeon Ringed Teal Toco Toucan (opening in late May) White-faced Saki monkey John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Africa: Chimpanzee Lion African ground hornbill Egyptian Geese Eastern Bongo Warthog Cape Porcupine (off exhibit) Von der Decken’s hornbill (off exhibit) Forest Realm: Amur Tigers Red Panda -

Sustainable Use of Wildland Resources: Ecological, Economic and Social Interactions

Sustainable Use of Wildland Resources: Ecological, Economic and Social Interactions An Analysis of Illegal Hunting of Wildlife in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania Ken Campbell, Valerie Nelson and Martin Loibooki June 2001 Main Report This report should be cited as: Campbell, K. L. I., Nelson, V. and Loibooki, M. (2001). Sustainable use of wildland resources, ecological, economic and social interactions: An analysis of illegal hunting of wildlife in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Department for International Development (DFID) Animal Health Programme and Livestock Production Programmes, Final Technical Report, Project R7050. Natural Resources Institute (NRI), Chatham, Kent, UK. 56 pp. 2 Sustainable Use of Wildland Resources: Ecological, Economic and Social Interactions An Analysis of Illegal Hunting of wildlife in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT, 2001 DFID Animal Health and Livestock Production Programmes, Project R7050 Ken Campbell1, Valerie Nelson2 Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich, Chatham, ME4 4TB, UK and Martin Loibooki Tanzania National Parks, P.O. Box 3134, Arusha, Tanzania Executive Summary A common problem for protected area managers is illegal or unsustainable extraction of natural resources. Similarly, lack of access to an often decreasing resource base may also be a problem for rural communities living adjacent to protected areas. In Tanzania, illegal hunting of both resident and migratory wildlife is a significant problem for the management of Serengeti National Park. Poaching has already reduced populations of resident wildlife, whilst over-harvesting of the migratory herbivores may ultimately threaten the integrity of the Serengeti ecosystem. Reduced wildlife populations may in turn undermine local livelihoods that depend partly on this resource. This project examined illegal hunting from the twin perspectives of conservation and the livelihoods of people surrounding the protected area. -

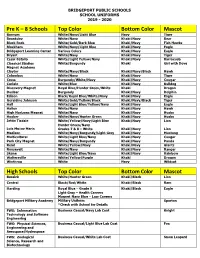

8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot

BRIDGEPORT PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL UNIFORMS 2019 - 2020 Pre K – 8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot Barnum White/Navy/Light Blue Navy Tiger Beardsley White/Navy Khaki/Navy Bear Black Rock White/Gold/Dark Blue Khaki/Navy Fish Hawks Blackham White/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Eagle Bridgeport Learning Center Various Colors Khaki/Navy Eagle Bryant White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger César Batalla White/Light Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Barracuda Classical Studies White/Burgundy Khaki Girl with Dove Magnet Academy Claytor White/Navy/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Hawk Columbus White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger Cross Burgundy/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Curiale White/Blue Khaki/Navy Bulldog Discovery Magnet Royal Blue/Hunter Green/White Khaki Dragon Dunbar Burgundy Khaki/Navy Dolphin Edison Black/Royal Blue/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Geraldine Johnson White/Gold/Yellow/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Tiger Hall White/Light Blue/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Hallen White/Navy Khaki/Navy Hawk High Horizons Magnet White/Navy Khaki/Navy Husky Hooker White/Navy/Hunter Green Khaki/Navy Husky Jettie Tisdale White/Yellow/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Lion Hunter Green/Navy Luis Muñoz Marín Grades 7 & 8 – White Khaki/Navy Lion Madison White/Navy/Burgundy/Light Grey Khaki/Navy Mustang Multicultural White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Park City Magnet White/Navy/Burgundy Khaki/Navy Panda Read White/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Giants Roosevelt White/Navy Khaki/Navy Ranger Skane White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Rainbow Waltersville White/Yellow/Purple Khaki Dragon Winthrop White Navy Wildcat -

Colours in Nature Colours

Nature's Wonderful Colours Magdalena KonečnáMagdalena Sedláčková • Jana • Štěpánka Sekaninová Nature is teeming with incredible colours. But have you ever wondered how the colours green, yellow, pink or blue might taste or smell? What could they sound like? Or what would they feel like if you touched them? Nature’s colours are so wonderful ColoursIN NATURE and diverse they inspired people to use the names of plants, animals and minerals when labelling all the nuances. Join us on Magdalena Konečná • Jana Sedláčková • Štěpánka Sekaninová a journey to discover the twelve most well-known colours and their shades. You will learn that the colours and elements you find in nature are often closely connected. Will you be able to find all the links in each chapter? Last but not least, if you are an aspiring artist, take our course at the end of the book and you’ll be able to paint as exquisitely as nature itself does! COLOURS IN NATURE COLOURS albatrosmedia.eu b4u publishing Prelude Who painted the trees green? Well, Nature can do this and other magic. Nature abounds in colours of all shades. Long, long ago people began to name colours for plants, animals and minerals they saw them in, so as better to tell them apart. But as time passed, ever more plants, animals and minerals were discovered that reminded us of colours already named. So we started to use the names for shades we already knew to name these new natural elements. What are these names? Join us as we look at beautiful colour shades one by one – from snow white, through canary yellow, ruby red, forget-me-not blue and moss green to the blackest black, dark as the night sky. -

Serengeti National Park Tanzania

SERENGETI NATIONAL PARK TANZANIA Twice a year ungulate herds of unrivalled size pour across the immense savanna plains of Serengeti on their annual migrations between grazing grounds. The river of wildebeests, zebras and gazelles, closely followed by predators are a sight from another age: one of the most impressive in the world. COUNTRY Tanzania NAME Serengeti National Park NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1981: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] INTERNATIONAL DESIGNATION 1981: Serengeti-Ngorongoro recognised as a Biosphere Reserve under the UNESCO Man & Biosphere Programme (2,305,100 ha, 1,476,300 ha being in Serengeti National Park). IUCN MANAGEMENT CATEGORY II National Park BIOGEOGRAPHICAL PROVINCE East African Woodland/Savanna (3.05.04) GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION In the far north of Tanzania 200 km west of Arusha, adjoining the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, between 1° 30' to 3° 20'S and 34° 00' to 35°15'E. DATES AND HISTORY OF ESTABLISHMENT 1929: Serengeti Game Reserve declared (228,600 ha) to preserve lions, previously seen as vermin; 1940: Declared a Protected Area; 1951: Serengeti National Park created, including Ngorongoro; boundaries were modified in 1959; 1981: Recognised as part of the Serengeti-Ngorongoro UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. LAND TENURE State, in Mara, Arusha and Shinyanga provinces. Administered by the Tanzanian National Parks Authority. AREA 1,476,300ha. It is contiguous in the southeast with Ngorongoro Conservation Area (809,440ha), in the southwest with Maswa Game Reserve (220,000ha), in the west with the Ikorongo-Grumeti Game Reserves (500,000ha), in the north with the Maasai-Mara National Reserve (151,000ha) in Kenya and in the northeast with the Loliondo Game Controlled Area (400,000ha). -

The Effect of Species Associations on the Diversity and Coexistence of African Ungulates

The effect of species associations on the diversity and coexistence of African ungulates. By Nancy Barker For Professor Kolasa BIO306H1 – Tropical Ecology University of Toronto Wednesday, August 24th, 2005 Abstract: The effects of species associations on species diversity and coexistence were investigated in East Africa. The frequency and group sizes of African ungulates were observed and analyzed to determine for differences in species associations based on their density and distribution, as well as their associations with other species. Associations between species were determined to be nonrandom and seen to affect the demographics of associating herds. Such associations mirrored in other studies were shown to be the result of interspecific competition, habitat preferences and predation pressure which increases the potential for coexistence between species. This suggests a potentially important role in the regulation of species diversity by ecological dynamics in species rich communities. In the face of today’s biodiversity crisis, such understanding of species associations and how they are regulated may have huge implications for conservation. Introduction: known with the famous Darwin’s finches of the Galapagos Islands. However, there are many other Sympatric coexistence of organisms within a guilds with what seems to be extensive community poses several questions for ecologists. overlapping in their resources, such as the grazing High levels of species association occur with high herds in Africa which eat common and widely species packing, as is seen within the Selous game dispersed foods. Sinclair (Sinclair, 1979 as cited in reserve of Tanzania in east Africa. Sinclair (1985) Sinclair, 1985) has found that this seemingly notes that mixed herds are frequently seen in east extensive overlap among these herds have also Africa and Connor and Simberloff (1979) have undergone niche separation. -

Aging Traits and Sustainable Trophy Hunting of African Lions

Aging traits and sustainable trophy hunting of African lions Authors: Jennifer R.B. Miller, Guy Balme, Peter A. Lindsey a,b, Andrew J. Loveridge, Matthew S. Becker,Colleen Begg, Henry Brink, Stephanie Dolrenry, Jane E. Hunt,Ingela Janssoni, David W. Macdonald,Roseline L. Mandisodza-Chikerema, Alayne Oriol Cotterill, Craig Packer,DanielRosengren, Ken Stratford, Martina Trinkel, Paula A. White, Christiaan Winterbach, Hanlie E.K. Winterbach, and Paul J. Funston NOTICE: this is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in Biological Conservation. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in Biological Conservation, [VOL# 201, (September 2016)]. DOI# 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.003 Miller, Jennifer R.B., Guy Balme, Peter A. Lindsey, Andrew J. Loveridge, Matthew S. Becker, Colleen Begg, Henry Brink, Stephanie Dolrenry, Jane E. Hunt, Ingela Jansson, David W. Macdonald, Roseline L. Mandisodza-Chikerema, Alayne Oriol Cotterill, Craig Packer, Daniel Rosengren, Ken Stratford, Martina Trinkel, Paula A. White, Christiaan Winterbach, Hanlie E.K. Winterbach, and Paul J. Funston. "Aging traits and sustainable trophy hunting of African lions." Biological Conservation 201 (September 2106): 160-168. Made available through Montana State University’s ScholarWorks scholarworks.montana.edu Aging traits and sustainable trophy hunting of African lions Jennifer R.B. Miller a,⁎, Guy Balme a, Peter A. Lindsey a,b, Andrew J. Loveridge c, Matthew S. Becker d,e, Colleen Begg f, Henry Brink g, Stephanie Dolrenry h, Jane E. -

Husbandry Guidelines for African Lion Panthera Leo Class

Husbandry Guidelines For (Johns 2006) African Lion Panthera leo Class: Mammalia Felidae Compiler: Annemarie Hillermann Date of Preparation: December 2009 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name: Certificate III Captive Animals Course Number: RUV 30204 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld, Brad Walker DISCLAIMER The information within this document has been compiled by Annemarie Hillermann from general knowledge and referenced sources. This document is strictly for informational purposes only. The information within this document may be amended or changed at any time by the author. The information has been reviewed by professionals within the industry, however, the author will not be held accountable for any misconstrued information within the document. 2 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS Wildlife facilities must adhere to and abide by the policies and procedures of Occupational Health and Safety legislation. A safe and healthy environment must be provided for the animals, visitors and employees at all times within the workplace. All employees must ensure to maintain and be committed to these regulations of OHS within their workplace. All lions are a DANGEROUS/ HIGH RISK and have the potential of fatally injuring a person. Precautions must be followed when working with lions. Consider reducing any potential risks or hazards, including; Exhibit design considerations – e.g. Ergonomics, Chemical, Physical and Mechanical, Behavioural, Psychological, Communications, Radiation, and Biological requirements. EAPA Standards must be followed for exhibit design. Barrier considerations – e.g. Mesh used for roofing area, moats, brick or masonry, Solid/strong metal caging, gates with locking systems, air-locks, double barriers, electric fencing, feeding dispensers/drop slots and ensuring a den area is incorporated.