Page 1 of 10 Touchstone Climbing: Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling with Liability: Encouraging Climbing on Private Land Page 9

VERTICAL TIMESSection The National Publication of the Access Fund Winter 09/Volume 86 www.accessfund.org Wrestling with Liability: Encouraging Climbing on Private Land page 9 CHOOSING YOUR COnseRvatION STRateGY 6 THE NOTORIOUS HORsetOOTH HanG 7 Winter 09 Vertical Times 1 QUeen CReeK/OaK Flat: NEGOTIATIONS COntINUE 12 AF Perspective “ All the beautiful sentiments in the world weigh less than a single lovely action.” — James Russell Lowell irst of all, I want to take a moment to thank you for all you’ve done to support us. Without members and donors like you, we would fall short F of accomplishing our goals. I recently came across some interesting statistics in the Outdoor Foundation’s annual Outdoor Recreation Participation Report. In 2008, 4.7 million people in the United States participated in bouldering, sport climbing, or indoor climbing, and 2.3 million people went trad climbing, ice climbing, or mountaineering. It is also interesting to note that less than 1% of these climbers are members of the Access Fund. And the majority of our support comes from membership. We are working on climbing issues all across the country, from California to Maine. While we have had many successes and our reach is broad, just imagine what would be possible if we were able to increase our membership base: more grants, more direct support of local climbing organizations, and, ultimately, more climbing areas open and protected. We could use your help. Chances are a number of your climbing friends and partners aren’t current Access Fund members. Please take a moment to tell them about our work and the impor- tance of joining us, not to mention benefits like discounts on gear, grants for local projects, timely information and alerts about local access issues, and a subscrip- tion to the Vertical Times. -

Meet the Tireles Climbers Establishing Moderate Sport Routes Around The

the mod squad Meet the tireles climbers establishing moderate sport routes around the country. STORY BY JOHANNA FLASHMAN PHOTO BY TK PHOTO BY TK 58 CLIMBING MAGAZINE Lindsay Wescott on the popular Free Willie (5.11a), Animal World, Boulder Canyon, CO. The climb is one of hundreds of moderate PHOTO BY TK PHOTO BY TK sport climbs put up by the Colorado developer Greg Hand (p.64). CLIMBING.COM 59 TK caption needed PHOTO BY TK PHOTO BY TK 58 CLIMBING MAGAZINE the mod squad Meet the climbers establishing moderate sport routes around the country. STORY BY JOHANNA FLASHMAN PHOTO BY TK PHOTO BY TK CLIMBING.COM 59 s a climber who doesn’t plan on breaking any records possibility of establishing multiple new routes in a day. This or even leading a 5.12 any time soon, I tend to seek made sport climbing a less elite, less esoteric pursuit, and soon AA out the 5.10-and-under climbs at my local cliffs. I like bolt-only face climbs of all grades began to appear across the climbs that don’t make me contemplate my mortality on every country. Concurrent was the ascension of climbing gyms, of move, as I suspect the majority of us do as well. Still, the media which there are now 530 and counting in America according to so often focuses on the climbers ticking 5.15s—the Adam Ondras the Climbing Business Journal. With the boom in gyms, which and Margo Hayeses of the world—when so few of us attain these are most new climbers’ introduction to the sport and offer fun, grades. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Wall Free Climb in the World by Tommy Caldwell

FREE PASSAGE Finding the path of least resistance means climbing the hardest big- wall free climb in the world By Tommy Caldwell Obsession is like an illness. At first you don't realize anything is happening. But then the pain grows in your gut, like something is shredding your insides. Suddenly, the only thing that matters is beating it. You’ll do whatever it takes; spend all of your time, money and energy trying to overcome. Over months, even years, the obsession eats away at you. Then one day you look in the mirror, see the sunken cheeks and protruding ribs, and realize the toll taken. My obsession is a 3,000-foot chunk of granite, El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. As a teenager, I was first lured to El Cap because I could drive my van right up to the base of North America’s grandest wall and start climbing. I grew up a clumsy kid with bad hand-eye coordination, yet here on El Cap I felt as though I had stumbled into a world where I thrived. Being up on those steep walls demanded the right amount of climbing skill, pain tolerance and sheer bull-headedness that came naturally to me. For the last decade El Cap has beaten the crap out of me, yet I return to scour its monstrous walls to find the tiniest holds that will just barely go free. So far I have dedicated a third of my life to free climbing these soaring cracks and razor-sharp crimpers. Getting to the top is no longer important. -

This Is Me Waking up 1000Ft up on El Cap's North America Wall

This is me waking up 1000ft up on El Cap's North America Wall. I am not overly psyched. Although you cannot see it in the photo, at this point I was being blasted by ice cold wind, being showered with bits of ice and I had a knee that had seized up. My psyche level was around 1 out of 10 and despite sort-of hoping that things would sort themselves out, I had pretty much already decided to bail. I really did not come here to bail but somehow the idea of going back down is, on the whole, more reasonable when you are on a route compared with when thinking about it at home. So, what was meant to be my first big-wall solo, became my first big-wall bail. ~- x -~ A week earlier I arrived in San Francisco. It was after a pretty hectic week and I was knackered, I think, due to this, somehow I managed to lose my wallet between airports. It took a while to accept this - I do not lose things. Boring story really; but I made contact with friends-of-friends, crashed at theirs and spent the next 48 hours getting cash via Western Union and finding somewhere that would rent a car using photos of a debit card and a counterpart driving licence. I arrived in a cold and rainy Yosemite Valley on the 7th of May and, with no a tent, I set to work to find a bivi with a roof. Once found, I went shopping for the gear and converted the car boot in my gear store/wardrobe. -

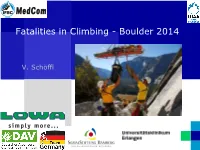

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014 V. Schöffl Evaluation of Injury and Fatality Risk in Rock and Ice Climbing: 2 One Move too Many Climbing: Injury Risk Study Type of climbing (geographical location) Injury rate (per 1000h) Injury severity (Bowie, Hunt et al. 1988) Traditional climbing, bouldering; some rock walls 100m high 37.5 a Majority of minor severity using (Yosemite Valley, CA, USA) ISS score <13; 5% ISS 13-75 (Schussmann, Lutz et al. Mountaineering and traditional climbing (Grand Tetons, WY, 0.56 for injuries; 013 for fatalities; 23% of the injuries were fatal 1990) USA) incidence 5.6 injuries/10000 h of (NACA 7) b mountaineering (Schöffl and Winkelmann Indoor climbing walls (Germany) 0.079 3 NACA 2; 1999) 1 NACA 3 (Wright, Royle et al. 2001) Overuse injuries in indoor climbing at World Championship NS NACA 1-2 b (Schöffl and Küpper 2006) Indoor competition climbing, World championships 3.1 16 NACA 1; 1 NACA 2 1 NACA 3 No fatality (Gerdes, Hafner et al. 2006) Rock climbing NS NS 20% no injury; 60% NACA I; 20% >NACA I b (Schöffl, Schöffl et al. 2009) Ice climbing (international) 4.07 for NACA I-III 2.87/1000h NACA I, 1.2/1000h NACA II & III None > NACA III (Nelson and McKenzie 2009) Rock climbing injuries, indoor and outdoor (NS) Measures of participation and frequency of Mostly NACA I-IIb, 11.3% exposure to rock climbing are not hospitalization specified (Backe S 2009) Indoor and outdoor climbing activities 4.2 (overuse syndromes accounting for NS 93% of injuries) Neuhhof / Schöffl (2011) Acute Sport Climbing injuries (Europe) 0.2 Mostly minor severity Schöffl et al. -

White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015

RUMNEY ROCKS CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015 Introduction The Rumney Rocks Climbing Area encompasses approximately 150 acres on the south-facing slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in Rumney, New Hampshire. Scattered across these slopes are approximately 28 rock faces known by the climbing community as "crags." Rumney Rocks is a nationally renowned sport climbing area with a long and rich climbing history dating back to the 1960s. This unique area provides climbing opportunities for those new to the sport as well as for some of the best sport climbers in the country. The consistent and substantial involvement of the climbing community in protection and management of this area is a testament to the value and importance of Rumney Rocks. This area has seen a dramatic increase in use in the last twenty years; there were 48 published climbing routes at Rumney Rocks in Ed Webster's 1987 guidebook Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and are over 480 documented routes today. In 2014 an estimated 646 routes, 230 boulder problems and numerous ice routes have been documented at Rumney. The White Mountain National Forest Management Plan states that when climbing issues are "no longer effectively addressed" by application of Forest Plan standards and guidelines, "site specific climbing management plans should be developed." To address the issues and concerns regarding increased use in this area, the Forest Service developed the Rumney Rocks Climbing Management Plan (CMP) in 2008. Not only was this the first CMP on the White Mountain National Forest, it was the first standalone CMP for the US Forest Service. -

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines

Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines Compiled for the Victorian Climbing Community Revision: V04 Published: 15 Sept 2020 1 Contributing Authors: Matthew Brooks - content manager and writer Ashlee Hendy Leigh Hopkinson Kevin Lindorff Aaron Lowndes Phil Neville Matthew Tait Glenn Tempest Mike Tomkins Steven Wilson Endorsed by: Crag Stewards Victoria VICTORIAN CLIMBING MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES V04 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 2 Foreword - Consultation Process for The Victorian Climbing Management Guidelines The need for a process for the Victorian climbing community to discuss widely about best rock-climbing practices and how these can maximise safety and minimise impacts of crag environments has long been recognised. Discussions on these themes have been on-going in the local Victorian and wider Australian climbing communities for many decades. These discussions highlighted a need to broaden the ways for climbers to build collaborative relationships with Traditional Owners and land managers. Over the years, a number of endeavours to build and strengthen such relationships have been undertaken; Victorian climbers have been involved, for example, in a variety of collaborative environmental stewardship projects with Land Managers and Traditional Owners over the last two decades in particular, albeit in an ad hoc manner, as need for such projects have become apparent. The recent widespread climbing bans in the Grampians / Gariwerd have re-energised such discussions and provided a catalyst for reflection on the impacts of climbing, whether inadvertent or intentional, negative or positive. This has focussed considerations of how negative impacts on the environment or cultural heritage can be avoided or minimised and on those climbing practices that are most appropriate, respectful and environmentally sustainable. -

Belaying » Get It Right!

BeLaYing » get it right! British Mountaineering Council Working for Climbers, hill Walkers and Mountaineers CheCk Harness CheCk KnOT CheCk BeLaY PAY aTTENTiOn! KnOw how to use your gear there are many different ropes and belaying devices available. read and understand the manufacturer’s instructions. if still unsure, get advice from someone more experienced. never belay with equipment you do not know how to use. COnTrol the rOpe Belaying is a complex skill requiring practice and experience to become competent. inattentive belaying is the cause of many preventable climbing accidents. Mistakes can result in serious injuries for climber, belayer or both. Check both climber’s knot and belay device before starting a climb. ensure your rope is long enough for your climb. if in doubt knot the free rope end. Pay attention and keep a controlling hand on the rope. geT in the BesT pOsiTiOn Anticipate the direction of pull, and position yourself appropriately. if you stand near the foot of a climb you are less likely to be pulled off balance when holding a fall or lowering a climber. if there is a lot of rope paid out the climber could hit the ground. Standing near the climb results in less rope between belayer and climber. When the climber is not moving, hold the rope in the locked position. suppOrT BriTisH CLiMBing – jOin THe BMC TOdaY: WWW.THeBMC.Co.uk T: 0161 445 6111 Belay deviCe deSign there are two types of belay device: manual devices and assisted braking devices. A manual device employs mainly friction, allowing some rope slippage when holding a fall. -

Korona VI, South Face, Georgian Direct

AAC Publications Korona VI, South Face, Georgian Direct Kyrgyzstan, Ala Archa National Park After staying a few days in the Ratsek Hut, Giorgi Tepnadze and I hiked up to the Korona Hut, a demotivating place due to its poor condition and interior design. We first went to the foot of Free Korea Peak to inspect a route we planned to try on the north face, and then set up camp below Korona’s less frequently climbed Sixth Tower (one of the highest Korona towers at 4,860m), at the head of the Ak-Sai Glacier. We began our climb on July 9, on a rightward slanting ramp to the right of known routes on the south face. After some moderate mixed climbing, we headed up a direct line for four difficult pitches: dry tooling with and without crampons; aid climbing up to A2+; free climbing with big (yet safe) fall potential, and then a final traverse left to cross a wide snow shelf and couloir. On the next pitch, starting up a steep rock wall, we spotted pitons and rappel slings; the rock pitches involved steep free climbing to 5c. The ninth pitch was wet, and above this we constructed a bivouac under a steep rock barrier, after several hours of dedicated effort. Next day was Giorgi’s turn to lead. The weather was horrible, and Giorgi had to dance the vertical in plastic boots. However, we tried our best to free as much as we could. Surprisingly, we found pitons on two pitches, before we made a leftward traverse, and more as we aided a wet chimney. -

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988 The Editorial Board expresses its deep gratitude to the many people who have done so much to make this section possible. We cannot list them all here, but we should like to give particular thanks to the following: Kamal K. Guha, Harish Kapadia, Soli S. Mehta, H.C. Sarin, P.C. Katoch, Zafarullah Siddiqui, Josef Nyka, Tsunemichi Ikeda, Trevor Braham, Renato More, Mirella Tenderini. Cesar Morales Arnao, Vojslav Arko, Franci Savenc, Paul Nunn, Do@ Rotovnik, Jose Manuel Anglada, Jordi Pons, Josep Paytubi, Elmar Landes, Robert Renzler, Sadao Tambe, Annie Bertholet, Fridebert Widder, Silvia Metzeltin Buscaini. Luciano Ghigo, Zhou Zheng. Ying Dao Shui, Karchung Wangchuk, Lloyd Freese, Tom Elliot, Robert Seibert, and Colin Monteath. METERS TO FEET Unfortunately the American public seems still to be resisting the change from feet to meters. To assist readers from the more enlightened countries, where meters are universally used, we give the following conversion chart: meters feet meters feet meters feet meters feet 3300 10,827 4700 15,420 6100 20,013 7500 24,607 3400 11,155 4800 15,748 6200 20,342 7600 24,935 3500 11,483 4900 16,076 6300 20,670 7700 25,263 3600 11,811 5000 16,404 6400 20,998 7800 25,591 3700 12,139 5100 16,733 6500 21,326 7900 25,919 3800 12,467 5200 17.061 6600 21,654 8000 26,247 3900 12,795 5300 7,389 6700 21,982 8100 26,575 4000 13,124 5400 17,717 6800 22,3 10 8200 26,903 4100 13,452 5500 8,045 6900 22,638 8300 27,231 4200 13,780 5600 8,373 7000 22,966 8400 27,560 4300 14,108 5700 8,701 7100 23,294 8500 27,888 4400 14,436 5800 19,029 7200 23,622 8600 28,216 4500 14,764 5900 9,357 7300 23,951 8700 28,544 4600 15,092 6000 19,685 7400 24,279 8800 28,872 NOTE: All dates in this section refer to 1988 unless otherwise stated.