Folk Music in Contemporary Nigeria: Continuity and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Landscape Adaptation And

NYAME AKUMA No. 72 December 2009 NIGERIA owner of the new farm. Berom men do this in turns until everyone has his own farm. But apart from pro- Cultural Landscape Adaptation and viding food for the work party, the wife or wives is/ Management among the Berom of are usually responsible for subsequent weeding in Central Nigeria order to ensure good harvests. The Berom people practice both cereal and tuber forms of agriculture. Samuel Oluwole Ogundele and James Local crops include millets, sorghum, cocoyam, po- Lumowo tato, cassava and yam. Berom farmers – men and Department of Archaeology and women – usually fence their farms with cacti. This is Anthropology an attempt to prevent the menace of domestic ani- University of Ibadan mals such as goats and sheep that often destroy Ibadan, Nigeria crops. [email protected] Apart from farming, the Berom men do practice hunting to obtain protein. Much of this game meat is also sold at the local markets. Hunting can be done Introduction on an individual or group basis. Some of the locally available game includes cane rats, monkeys, ante- This paper reports preliminary investigations lopes and porcupines. According to the available oral conducted in April and May 2009, of archaeological tradition, Beromland was very rich in animal resources and oral traditions among the Berom of Shen in the including tigers, elephants, lions and buffalos in the Du District of Plateau State, Nigeria. Berom people olden days. However, over-killing or indiscriminate are one of the most populous ethnicities in Nigeria. hunting methods using bows and arrows and spears Some of the districts in Beromland are Du, Bachi, have led to the near total disappearance of these Fan, Foron, Gashish, Gyel, Kuru, Riyom and Ropp. -

The Journey of Vodou from Haiti to New Orleans: Catholicism

THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND IT’S TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College by Tyler Janae Smith San Marcos, Texas December 2015 THE JOURNEY OF VODOU FROM HAITI TO NEW ORLEANS: CATHOLICISM, SLAVERY, THE HAITIAN REVOLUTION IN SAINT- DOMINGUE, AND ITS TRANSITION TO NEW ORLEANS IN THE NEW WORLD by Tyler Janae Smith Thesis Supervisor: _____________________________ Ronald Angelo Johnson, Ph.D. Department of History Approved: _____________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College Abstract In my thesis, I am going to delve into the origin of the religion we call Vodou, its influences, and its migration from Haiti to New Orleans from the 1700’s to the early 1800’s with a small focus on the current state of Vodou in New Orleans. I will start with referencing West Africa, and the religion that was brought from West Africa, and combined with Catholicism in order to form Vodou. From there I will discuss the effect a high Catholic population, slavery, and the Haitian Revolution had on the creation of Vodou. I also plan to discuss how Vodou has changed with the change of the state of Catholicism, and slavery in New Orleans. As well as pointing out how Vodou has affected the formation of New Orleans culture, politics, and society. Introduction The term Vodou is derived from the word Vodun which means “spirit/god” in the Fon language spoken by the Fon people of West Africa, and brought to Haiti around the sixteenth century. -

Influence of Traditional Art of Africa on Contemporary Art Praxis: the Ibibio Funerary Art Example

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2020, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 54-61 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v8n2p5 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v8n2p5 Influence of Traditional Art of Africa on Contemporary Art Praxis: The Ibibio Funerary Art Example Ime Ukim1, Ph.D Abstract African art, with exception of Egyptian art, has suffered scholastic neglect as only a little scholarship has been done regarding them. This has resulted in the misconception that traditional African art contributes little or nothing to the development of contemporary art. This paper, in an attempt to dispel such misconception, projects an aspect of indigenous Ibibio art praxis - funerary art to reveal Ibibio art culture‟s influence on contemporary art praxis. The objectives are to identify traditional Ibibio funerary art forms; highlight its transformation; and examine its influence on contemporary art praxis. It benefits from analogue and digital library sources, and information sought from interviews of knowledgeable persons in the locality. Findings reveal that traditional Ibibio funerary art forms, which include ekpu carvings, paintings and drawings on ‟Nwommo‟and „Iso Nduongo‟ shrines and ekpo mask carvings, form a bedrock on which a great deal of contemporary art praxis within Ibibio land and its environs rests, as contemporary African art is an extension of traditional African art. The paper, therefore, recommends that more scholastic work be carried out on African art cultures for more revelations of their contributions to the development of contemporary art. -

POLICING REFORM in AFRICA Moving Towards a Rights-Based Approach in a Climate of Terrorism, Insurgency and Serious Violent Crime

POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, Mutuma Ruteere & Simon Howell POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, University of Jos, Nigeria Mutuma Ruteere, UN Special Rapporteur, Kenya Simon Howell, APCOF, South Africa Acknowledgements This publication is funded by the Ford Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, and the Open Societies Foundation. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect their positions or policies. Published by African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Copyright © APCOF, April 2018 ISBN 978-1-928332-33-6 African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Building 23b, Suite 16 The Waverley Business Park Wyecroft Road Mowbray, 7925 Cape Town, ZA Tel: +27 21 447 2415 Fax: +27 21 447 1691 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apcof.org.za Cover photo taken in Nyeri, Kenya © George Mulala/PictureNET Africa Contents Foreword iv About the editors v SECTION 1: OVERVIEW Chapter 1: Imperatives of and tensions within rights-based policing 3 Etannibi E. O. Alemika Chapter 2: The constraints of rights-based policing in Africa 14 Etannibi E.O. Alemika Chapter 3: Policing insurgency: Remembering apartheid 44 Elrena van der Spuy SECTION 2: COMMUNITY–POLICE NEXUS Chapter 4: Policing in the borderlands of Zimbabwe 63 Kudakwashe Chirambwi & Ronald Nare Chapter 5: Multiple counter-insurgency groups in north-eastern Nigeria 80 Benson Chinedu Olugbuo & Oluwole Samuel Ojewale SECTION 3: POLICING RESPONSES Chapter 6: Terrorism and rights protection in the Lake Chad basin 103 Amadou Koundy Chapter 7: Counter-terrorism and rights-based policing in East Africa 122 John Kamya Chapter 8: Boko Haram and rights-based policing in Cameroon 147 Polycarp Ngufor Forkum Chapter 9: Police organizational capacity and rights-based policing in Nigeria 163 Solomon E. -

The Singer As Priestess

-, ' 11Ie Singer as Priestess: Interviews with Celina Gonzatez and Merceditas Valdes ".:" - , «1',..... .... .. (La Habana, 1993) Ivor Miller Celina Gonzalez: Queen of the Punto Cubano rummer Ivan Ayala) grew up in New York City listening to the music of Celina Gonzalez. * As Da child in the 1960s he was brought to Puerto Rican espiritista ceremonies, where instead of using drums, practitioners would play Celina's records to invoke the spirits. This is one way that Celina's music and the dedication of her followers have blasted through the U.S. embargo against Cuba that has deprived us of some of the planet's most potent music, art and literature for over 32 years. Ivan's experi ence shows the ingenuity of working people in maintaining human connections that are essential to them, in spite of governments that would keep them separate. Hailed as musical royalty in Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, England and in Latin USA, Celina has, until very recently, been kept out of the U.S. n:tarket.2 Cuba has long been a mecca for African-derived religious and musical traditions, and Celina's music taps a deep source. It is at the same time popular and sacred, danceable and political. By using the ancient Spanish dicima song form to sing about the Yoruba deities (orichas), she has become a symbol of Cuban creole (criollo) traditions. A pantheon of orichas are worshipped in the Santeria religion, which is used by practitioners to protect humans from sickness and death, and to open the way for peace, stability, and success. During the 14 month period that I spent in Cuba from 1991-1994, I had often heard Celina's music on the radio, TV, and even at a concert/rally for the Young Communist League (UJC), where the chorus of "Long live Chango'" ("iQueviva Chango!") was chanted by thou Celina Gonzalez (r) and [dania Diaz (l) injront o/Celina's Santa sands of socialist Cuba's "New Men" at the Plaza of the Revolution.3 Celina is a major figure in Cuban music and cultural identity. -

Okanga Royal Drum: the Dance for the Prestige and Initiates Projecting Igbo Traditional Religion Through Ovala Festival in Aguleri Cosmolgy

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 3, pp.19-49, March 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), Online ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) OKANGA ROYAL DRUM: THE DANCE FOR THE PRESTIGE AND INITIATES PROJECTING IGBO TRADITIONAL RELIGION THROUGH OVALA FESTIVAL IN AGULERI COSMOLGY Madukasi Francis Chuks, PhD ChukwuemekaOdumegwuOjukwu University, Department of Religion & Society. Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria. PMB 6059 General Post Office Awka. Anambra State, Nigeria. Phone Number: +2348035157541. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: No literature I have found has discussed the Okanga royal drum and its elements of an ensemble. Elaborate designs and complex compositional ritual functions of the traditional drum are much encountered in the ritual dance culture of the Aguleri people of Igbo origin of South-eastern Nigeria. This paper explores a unique type of drum with mystifying ritual dance in Omambala river basin of the Igbo—its compositional features and specialized indigenous style of dancing. Oral tradition has it that the Okanga drum and its style of dance in which it figures originated in Aguleri – “a farming/fishing Igbo community on Omambala River basin of South- Eastern Nigeria” (Nzewi, 2000:25). It was Eze Akwuba Idigo [Ogalagidi 1] who established the Okanga royal band and popularized the Ovala festival in Igbo land equally. Today, due to that syndrome and philosophy of what I can describe as ‘Igbo Enwe Eze’—Igbo does not have a King, many Igbo traditional rulers attend Aguleri Ovala festival to learn how to organize one in their various communities. The ritual festival of Ovala where the Okanga royal drum features most prominently is a commemoration of ancestor festival which symbolizes kingship and acts as a spiritual conduit that binds or compensates the communities that constitutes Eri kingdom through the mediation for the loss of their contact with their ancestral home and with the built/support in religious rituals and cultural security of their extended brotherhood. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

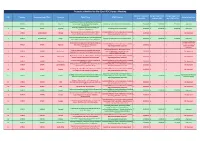

Projects Submitted to the 62Nd IPDC Bureau Meeting

Projects submitted to the 62nd IPDC Bureau Meeting Amount requested Budget approved Budget approved NO. Region Implementing Office Country Title / Titre IPDC Priority Bureau Decision from IPDC without PSC with PSC of 7% Strenghtening Kakaki community radio for improved 1 AFRICA ABUJA Nigeria service delivery and enhanced community Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,070.00 $ 20,320.00 $ 21,742.40 Approved participation Promoting Media Development and Safety of 2 AFRICA ACCRA Regional Promoting Safety of Journalists $ 34,500.00 $ 23,000.00 $ 24,610.00 Approved Journalists in West Africa Building journalism educators´capacity of Jimma Capacity building for media professionals, including 3 AFRICA ADDIS ABABA Ethiopia $ 16,749.00 $ - $ - Not Approved University through audio visual skill training improving journalism education Renforcement des capacités de la radio citoyenne des 4 AFRICA BRAZZAVILLE Congo Supporting media pluralism and independence $ 20,690.00 $ 18,000.00 $ 19,260.00 Approved jeunes pour la promotion des valeurs citoyennes Not approved (To be Renforcement de capacités et de moyens du Réseau Capacity building for media professionals, including resubmitted next year 5 AFRICA DAKAR Regional des radios en Afrique de l´Ouest pour $ 19,500.00 $ - $ - improving journalism education with an improved l´environnement proposal) Countering hate speech, promoting conflict- Projet de renforcement des capacités des femmes 6 AFRICA DAKAR Burkina Faso sensitive journalism or promoting cross- $ 20,000.00 $ - $ - Not Approved animatrices -

UNIVERSITY of IBADAN LIBRARY F~Fiva23ia Mige'tia: Abe Ky • by G.D

- / L. L '* I L I Nigerla- magazine - # -\ I* .. L I r~.ifr F No. 136 .,- e, .0981 W1.50r .I :4 UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY F~fiva23ia Mige'tia: ABe ky • By G.D. EKPENYONG (MRS) HIS BIBLIOGRAPHY IS COMING OUT AT A TIME TRADITIONAL RULERS ENCOURAGED THEIR PEOPLE TO AC- T WHEN THERE IS GENERAL OR NATIONAL AWARENESS CEPT ISLAM AND AS A CONSEQUENCE ACCEPT IT AND FOR THE REVIVAL OF OUR CULTURAL HERITage. It IS HOPED CELEBRATED FESTIVALS ASSOCIATED WITH THIS religion. THAT NIGERIANS AND ALIENS RESIDENT IN NigeRIa, FESTIVALS ARE PERIODIC RECURRING DAYS OR SEA- RESEARCHERS IN AFRICAN StudiES, WOULD FIND THIS SONS OF GAIETY OR MERRy-maKING SET ASIDE BY A PUBLICATION A GUIDE TO A BETTER KNOWLEDGE OF THE COMMUNITY, TRIBE OR CLAN, FOR THE OBSERVANCE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE AND DIVERSITY OF THE PEOPLES OF SACRED CELEBRATIOns, RELIGIOUS SOLEMNITIES OR MUs- NIGERIA. ICAL AND TRADITIONAL PERFORMANCE OF SPECIAL SIG- IT IS NECESSARY TO EMPHASISe, HOWEVER, THAT NIFICANCE. It IS AN OCCASION OF PUBLIC MANIFesta- ALTHOUGH THIS IS A PIONEERING EFFORT TO RECORD ALL TION OF JOY OR THE CELEBRATION OF A HISTORICAL OC- THE KNOWN AND UNKNOWN TRADITIONAL FESTIVALS CURRENCE LIKE THE CONQUEST OF A NEIGHBOURING HELD ANNUALLY OR IN SOME CASES, AFTER A LONG VILLAGE IN WAR. IT CAN TAKE THE FORM OF A RELIGIOUS INTERVAL OF TIMe, THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY IS BY NO MEANS CELEBRATION DURING WHICH SACRIFICES ARE OFFERED TO EXHAUSTIVE. THE DIFFERENT GODS HAVING POWER OVER RAIN, Sun- SHINE, MARRIAGE AND GOOD HARVEST. Introduction He IS THE MOST ANCIENT OF ALL YORUBA TOWNS AND NigerIa, ONE OF THE LARGEST COUNTRIES IN AFRIca, IS REGARDED BY ALL YORUBAS AS THE FIRST CITY FROM IS RICH IN CULTURE AND TRADITIOn. -

Elenco Provvisorio Degli Enti Del Volontariato 2012

Elenco provvisorio degli enti del volontariato 2012: dalla lettera D alla lettera Z CODICE DENOMINAZIONE FISCALE INDIRIZZO COMUNE CAP PR 1 D COME DONNA 91531260155 LARGO CARABINIERI D'ITALIA 1 SEGRATE 20090 MI VIALE XXIV MAGGIO SNC(C/O OSP 2 D- PROJECT ONLUS 90062510582 SAN G MARINO 00047 RM 3 D.A.S. DIRITTO ALLA SALUTE ONLUS 92034880606 PIAZZA INNOCENZO III N 10 ANAGNI 03012 FR 4 D.J. CAMPANIA 95156590630 VIA CALATA S MARCO 4 NAPOLI 80132 NA 5 D.O.M.O. DONATORI OSSOLANI MIDOLLO OSSEO 92008890037 LARGO CADUTI LAGER NAZISTI N 1 DOMODOSSOLA 28845 VB 6 D.U.C.A. ONLUS 92542140154 VIA STREPPONI N 30 LODI 26900 LO DA AMICI VIVIAMO INSIEME DIVIDENDO ESPERIENZE 7 SOC.COOP. SOCIALE A R.L. - DAVIDE 02170610303 VIA MATTEOTTI 19/G TOLMEZZO 33028 UD 8 DA DONNA A DONNA ONUS 02918610797 VIA CAVOUR,CONDOMINIO SIRIO VIBO VALENTIA 89900 VV 9 DA KUCHIPUDI A.... 95089980247 C SO S S FELICE E FORTUNATO 108 VICENZA 36100 VI 10 DA QUI ALL'UMANITA' 97468120585 VIA GIAMPIETRO FERRARI 19 ROMA 00126 RM 11 DACCAPO - ASSOCIAZIONE TRAUMA CRANICO 92170370289 VIA SANTA MARIA IN VANZO 27 PADOVA 35123 PD DACHVERBAND FUER NATUR UND UMWELTSCHUTZ IN 12 SUEDTIROL 94005310217 KORNPLATZ 10 BOLZANO .BOZEN. 39100 BZ DACHVERBAND FUER SOZIALES UND GESUNDHEIT/FEDERAZIONE PER IL SOCIALE E LA 13 SANITA 90011870210 VIA DR STREITER 4 BOLZANO .BOZEN. 39100 BZ SANT'AMBROGIO DI 14 DADA MAISHA 0NLUS 93192570237 VIA DELLA TORRE 2-B VALPOLICELLA 37015 VR STRADA SCARTAZZA 180 - SAN 15 DADA' SOCIETA' COOPERATIVA SOCIALE 03001710361 DAMASO MODENA 41100 MO 16 DADO MAGICO COOPERATIVA SOCIALE A R.L. -

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women's Sexuality

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women’s Sexuality Anke Becker* November 5, 2018 Abstract This paper studies the economic origins of customs aimed at constraining female sexuality, such as a particularly invasive form of female genital cutting, restrictions on women’s mobility, and norms about female sexual behavior. The analysis tests the anthropological theory that a particular form of pre-industrial economic pro- duction – subsisting on pastoralism – favored the adoption of such customs. Pas- toralism was characterized by heightened paternity uncertainty due to frequent and often extended periods of male absence from the settlement, implying larger payoffs to imposing constraints on women’s sexuality. Using within-country vari- ation across 500,000 women in 34 countries, the paper shows that women from historically more pastoral societies (i) are significantly more likely to have under- gone infibulation, the most invasive form of female genital cutting; (ii) are more restricted in their mobility, and hold more tolerant views towards domestic vio- lence as a sanctioning device for ignoring such constraints; and (iii) adhere to more restrictive norms about virginity and promiscuity. Instrumental variable es- timations that make use of the ecological determinants of pastoralism support a causal interpretation of the results. The paper further shows that the mechanism behind these patterns is indeed male absenteeism, rather than male dominance per se. JEL classification: I15, N30, Z13 Keywords: Infibulation; female sexuality; paternity uncertainty; cultural persistence. *Harvard University, Department of Economics and Department of Human Evolutionary Biology; [email protected]. 1 Introduction Customs, norms, and attitudes regarding the appropriate behavior and role of women in soci- ety vary widely across societies and individuals. -

1 Chapter Three Historical

University of Pretoria etd, Adeogun A O (2006) CHAPTER THREE HISTORICAL-CULTURAL BACKCLOTH OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN NIGERIA This chapter traces the developments of music education in the precolonial Nigeria. It is aimed at giving a social, cultural and historical background of the country – Nigeria in the context of music education. It describes the indigenous African music education system that has been in existence for centuries before the arrival of Islam and Christianity - two important religions, which have influenced Nigerian music education in no small measure. Although the title of this thesis indicates 1842-2001, it is deemed expedient, for the purposes of historical background, especially in the northern part of Nigeria, to dwell contextually on the earlier history of Islamic conquest of the Hausaland, which introduced the dominant musical traditions and education that are often mistaken to be indigenous Hausa/northern Nigeria. The Islamic music education system is dealt with in Chapter four. 3.0 Background - Nigeria Nigeria, the primarily focus of this study, is a modern nation situated on the Western Coast of Africa, on the shores of the Gulf of Guinea which includes the Bights of Benin and Biafra (Bonny) along the Atlantic Coast. Entirely within the tropics, it lies between the latitude of 40, and 140 North and longitude 20 501 and 140 200 East of the Equator. It is bordered on the west, north (northwest and northeast) and east by the francophone countries of Benin, Niger and Chad and Cameroun respectively, and is washed by the Atlantic Ocean, in the south for about 313 kilometres.