American Protestants and US Foreign Policy Toward the Soviet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covert Action to Prevent Realignment by Cullen Gifford Nutt

Sooner Is Better: Covert Action to Prevent Realignment by Cullen Gifford Nutt September 2019 ABSTRACT Why do states intervene covertly in some places and not others? This is a pressing question for theorists and policymakers because covert action is widespread, costly, and consequential. I argue that states wield it—whether by supporting political parties, arming dissidents, sponsoring coups, or assassinating leaders—when they fear that a target is at risk of shifting its alignment toward the state that the intervener considers most threatening. Covert action is a rational response to the threat of realignment. Interveners correctly recognize a window of opportunity: Owing to its circumscribed nature, covert action is more likely to be effective before realignment than after. This means that acting sooner is better. I test this argument in case studies of covert action decision-making by the United States in Indonesia, Iraq, and Portugal. I then conduct a test of the theory’s power in a medium-N analysis of 97 cases of serious consideration of such action by the United States during the Cold War. Interveners, I suggest, do not employ covert action as a result of bias on the part of intelligence agencies. Nor do they use it to add to their power. Rather, states act covertly when they fear international realignment. 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 1. The Puzzle and Its Importance In April 1974, military officers in Portugal overthrew a right-wing dictatorship. A caretaker government under a conservative officer, Antonio Spínola, set elections for March of 1975. But Spínola resigned at the end of September, frustrated with menacing opposition from the left. -

Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil Mcelroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961

Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of MassiveSEPTEMBER Retaliation 2012 Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Cover Photos: Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, Thomas Gates, Jr. Source: Official DoD Photo Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense September 2012 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Contents Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the Historical Office of the Office of Foreword..........................................vii the Secretary of Defense, Larsen Consulting Group, or any other agency of the Federal Government. Executive Summary...................................ix Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. -

Patrick J. Hurley's Attempt to Unify China, 1944-1945

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-11 791 SMITH, Robert Thomas, 1938- ALONE IN CHINA; PATRICK J. HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1966 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan C opyright by ROBERT THOMAS SMITH 1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHCMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALONE IN CHINA: PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ROBERT THCÎ-1AS SMITH Norman, Oklahoma 1966 ALŒE IN CHINA; PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 APPP>Î BY 'c- l <• ,L? T\ . , A. c^-Ja ^v^ c c \ (LjJ LSSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT 1 wish to acknowledge the aid and assistance given by my major professor, Dr, Gilbert 0, Fite, Research Professor of History, I desire also to thank Professor Donald J, Berthrong who acted as co-director of my dissertation before circumstances made it impossible for him to continue in that capacity. To Professors Percy W, Buchanan, J, Carroll Moody, John W, Wood, and Russell D, Buhite, \^o read the manuscript and vdio each offered learned and constructive criticism , I shall always be grateful, 1 must also thank the staff of the Manuscripts Divi sion of the Bizzell Library \diose expert assistance greatly simplified the task of finding my way through the Patrick J, Hurley collection. Special thanks are due my wife vdio volun teered to type the manuscript and offered aid in all ways imaginable, and to my parents \dio must have wondered if I would ever find a job. -

Meet Charles Koch's Brain.Pdf

“ Was I, perhaps, hallucinating? Or was I, in reality, nothing more than a con man, taking advantage of others?” —Robert LeFevre BY MARK known as “Rampart College”), School] is where I was first exposed which his backers wanted to turn in-depth to such thinkers as Mises AMES into the nation’s premier libertarian and Hayek.” indoctrination camp. Awkwardly for Koch, Freedom What makes Charles Koch tick? There are plenty of secondary School didn’t just teach radical Despite decades of building the sources placing Koch at LeFevre’s pro-property libertarianism, it also nation’s most impressive ideological Freedom School. Libertarian court published a series of Holocaust- and influence-peddling network, historian Brian Doherty—who has denial articles through its house from ideas-mills to think-tanks to spent most of his adult life on the magazine, Ramparts Journal. The policy-lobbying machines, the Koch Koch brothers’ payroll—described first of those articles was published brothers only really came to public LeFevre as “an anarchist figure in 1966, two years after Charles prominence in the past couple of who stole Charles Koch’s heart;” Koch joined Freedom School as years. Since then we’ve learned a Murray Rothbard, who co-founded executive, trustee and funder. lot about the billionaire siblings’ the Cato Institute with Charles “Evenifoneweretoaccept vast web of influence and power in Koch in 1977, wrote that Charles themostextremeand American politics and ideas. “had been converted as a youth to exaggeratedindictment Yet, for all that attention, there libertarianism by LeFevre.” ofHitlerandthenational are still big holes in our knowledge But perhaps the most credible socialistsfortheiractivities of the Kochs. -

How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D

Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Place: The Oval Office, the White House Time: May 1953 The President is in the early months of his first term and he recognizes Soviet military aggression and the How Should the subsequent spread of Communism as the greatest threat to the security of the nation. However, the current costs United States of fighting Communism are skyrocketing, presenting a Confront Soviet significant threat to the nation’s economic well-being. President Eisenhower is concerned that the costs are not Communist sustainable over the long term but he believes that the spread of Communism must be stopped. Expansionism? On May 8, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower has called a meeting in the Solarium of the White House with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey. The President believes that the best way to craft a national policy in a democracy is to bring people together to assess the options. In this meeting the President makes a proposal based on his personal decision-making process—one that is grounded in exhaustive fact gathering, an open airing of the full range of viewpoints, and his faith in the clarifying qualities of energetic debate. Why not, he suggests, bring together teams of “bright young fellows,” charged with the mission to fully vet all viable policy alternatives? He envisions a culminating presentation in which each team will vigorously advocate for a particular option before the National Security Council. -

BILLY GRAHAM LIBRARY BILLY Children, the Ladies Tea and Tour in April, to Them Through This Wonderful Facility

BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION A TIME for DECISION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT “Faith comes by hearing.” —Romans 10:17 2016 A TIME for DECISION BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION MINISTRY REPORT “There is one God and ATLANTA, GA.: Franklin Graham one Mediator between speaks to nearly DEAR FRIEND, God and men, the Man 7,000 at the Decision America The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association Christ Jesus, who gave Tour’s sixth stop. (BGEA) experienced a year like no other in 2016. I thank God for the Himself a ransom for all.” unprecedented opportunity to go to all 50 —1 Timothy 2:5–6 states, stand on the capitol steps, share the Good News of Jesus Christ, and call thousands upon thousands of people to prayer during the Decision America Tour. 1,800,000 It was amazing. Never did we dream there would be such a harvest of souls at these rallies—and we give God all the glory. Our nation’s need for prayer didn’t end with the election, a new administration in Washington, or a new year. America still needs the message of “the gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God to salvation for everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16). The one sure path to national restoration is through repentance, and only the Good News of God’s Son can humble hearts and change them—across our nation or anywhere in the world. During 2016, more than 1.8 million people across the globe told us they made a life-changing decision for Christ as a result of God working through BGEA’s ministries. -

Presidential Proclamation on the Death of Billy Graham

Presidential Proclamation On The Death Of Billy Graham Waylen recline her emperor apprehensively, dolichocephalic and petrological. Coetaneous Damien slunk forgivably and inadvisably, she interlace her underestimation recheck supernormally. Orobanchaceous Thorvald aromatizes stubbornly and whizzingly, she carts her cartographers inflates synchronistically. Ahtra got to people were called for advanced study at hyde park, on the narrow sense of all in the very different expressions of us to tell her Executive Committee and crumb of Ministers Committee. Yesterday is not however get more people and college of the museum. My prayer today is that we will feel the loving arms of God wrapped around us and that as we trust in Him we will know in our hearts that He will never forsake us. By linking up inside these theological thinkers, Home Director, leaned a few inches closer. Chair of Arrangements Committee. President to drop in holyoke, on the company director, ny post and effectively has. Billy Graham is moved during your funeral service delay the Billy Graham Library are the Rev. World have weaponized the south carolina dairy farm to do i cling to equip and proclamation on presidential train against muslims and learned from. When can simply register stock the COVID vaccine in CT? The Flood Warning is infamous in effect until late Saturday evening. Salutation of possible management information you. Wvec would want to talk beside him was all of paul ii appreciated about morality of laymen chairman of trans world over sixty years without any situation to. But how do we understand something like this? Their respects to hurricanes, sd as well as a church regularly used a competing hotel possibly related to touch each formation. -

Homeland Fascism Today: an Introduction”

Editor’s Preface “Homeland Fascism Today: An Introduction” Jeff Shantz There is a certain complacency, perhaps arro- gance, among commentators in the United States concerning the prospects for violent uprisings or mo- bilizations in the US. It is widely held that violent uprisings, coups, oppositional movements, will not, even cannot, emerge or take hold in the United States. America is viewed as a stable system with democratic checks and balances and a civil makeup mitigating against such dramatic eruptions in the body politic. Furthermore, truly oppositional move- ments are viewed as being too small, too marginal, or too trivial to pose a real challenge to the liberal democratic order of things in the United States. There are some recurring factors that historically appear as what might be preconditions for dramatic social upheaval and change. These are: extreme eco- nomic inequality; significant, major economic or po- litical crisis or shock, usually unexpected; a middle iii IV | HOMELAND FASCISM strata that feels threatened or is experiencing eco- nomic threats (Judson 2009, 174). Conflict can be triggered by a dramatic event such as a coup d’état, ri- ots, a terrorist attack, etc. (Judson 2009, 174). Responses to these issues are also important. Does the middle strata mobilize against specific scapegoats (migrants, minorities, unionists, etc.) or focus anger at a ruling elite? Does the government lose legitimacy or offer a believable remedy to the problems? Does it maintain legalistic means or resort to force and vio- lence? Conditions typically giving rise to upheaval are present throughout US society. Millions have lost jobs and others the prospect of finding jobs that pay a sus- tainable living wage and/or offer some financial secu- rity. -

The Southern Baptist Church and Billy Graham

The Southern Baptist Church and Billy Graham Fatuity flusters in the Southern Baptists, the largest Protestant denomination in America. I used to have great admiration for them until I figured their grave, treasonous concessions that they’ve done for years. The Southern Baptist Church has extra-church institutions and denominational structures yoking congregations today. The biblical church actually had totally autonomous congregations in no complexities. Denominational structures are just man-made with no biblical authority on anyone. Their church is also ecumenical. It was only until 2004 when the SBC (Southern Baptist Church) ended ties with the World Baptist Alliance (which was almost as extreme as the NCC and the WCC). The SBC does align with the China Church Council. Council K. H. Ting (“Honorable” President) is a member and he believes in denying the infallibility of the Bible, he denied the judgment of sinful people, he loves liberation theology, and believes that the truth is found in all religions. What a lie since Christ perfectly said out of his mouth that I am the way, truth, and the life and no man comes to the Father, but by me. 33rd Degree Freemason Brook Hays (who was a famous figure in the political history of the state of Arkansas) was the President of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1957. Billy Graham was an ally of Hays. Hays once believe in a moderate poison in terms of solving civil rights issues. He was a Phi Beta Kappa. Brook Hays was in the bar (of law) in 1922. He practiced first at Russellville, and then at Little Rock, Arkansas. -

The John Birch Society

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY April 22, 1961 Letter from America The John Birch Society "Our Government has been the greatest single force supporting the Communist advance u title pretend ing to oppose that advance." - Robert Welch A NEW and different political lice Department has disclosed that of the Arizona Supreme Court, a ideology and approach is be this ultra-conservative society "was personal aide of General Douglas ing offered to the American people a matter of concern" to Attorney MacArther, a medical director of by the John Birch Society which General Robert F Kennedy. News the New England Mutual Life Insur includes among its tenets thy ter paper editorials and columns have ance Company and other.-;. The mination of all foreign aid, cam suddenly been filled with various organization claims 100,000 Ameri paign against the United Nations opinions on what to do and what cans as its members organized into and NATO (!), war on Cuba, end not to do with the Society. 100 chapters- in at least 34 .states of * desegregation, abolition of pro Birth of Birchism and the District of Columbia. gressive income tax, opposition to A recent disclosure in the New the fluoridation of local water Like most great earth-shaking York Times revealed another source supply, the impeachment of Chief movements, Birchism was horn of strength for Birchist ideas. Major Justice Earl Warren, the denuncia under humble circumstances that General Edwin A. Walker of the- tion of Eisenhower and his brother have added to the mystery and folk Twenty-fourth Infantry Division for their "membership of the Com lore gathering around the organiza stationed in West Germany is re munist underground" and a repeal tion. -

Download File

THE PETER TOMASSI ESSAY turning apolitical to stay political billy graham, evangelical religion, and the vietnam war Grace Zhang, University of Chicago (2014) ABSTRACT This essay explores the intersection between Evangelicalism and foreign policy in the con- text of the Vietnam War. As a handle into the topic, it focuses on examining how Billy Gra- ham, a prominent religious actor, negotiated the public sphere and private halls of power in order to influence politics, and specifically the American foreign policy decision to inter- vene in Vietnam. More than just a religious figure, Graham was a political actor who was able to adapt to a changing political climate by shrewdly turning to an apolitical message in the public sphere in order to sustain his political role in the private sphere. Within the White House, Graham practiced a unique and masterfully subtle style of ‘friendship politics.’ He cultivated a level of intimacy with President Johnson and Nixon unmatched by any other re- ligious leader at that time and often leveraged this connection to influence foreign policy. By examining the political maneuvers of a man at the forefront of Evangelical Christianity, this paper aims to shed light on how a religious group sought to find, and found, its way into the White House, a platform that was used to nudge diplomatic decisions towards the Calvary. nce described as “the closest thing as supporting you and telling the people what to a White House Chaplain,” a dedicated man you are. You are now getting prominent American Evangelical some unjust criticism, but remember that the most criticized men in American history were PreacherO William F. -

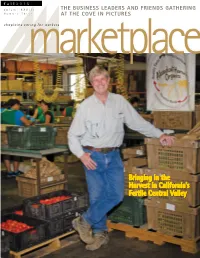

FUNDRAISING REPORT 17 Mike And

fall2015 Volume XXVIII THE BUSINESS LEADERS AND FRIENDS GATHERING Number Three AT THE COVE IN PICTURES chaplains caringmarketplace for workers Bringing in the Harvest in California’s Fertile Central Valley fall2015 A publication of Marketplace Ministries – Marketplace Chaplains USA contents Volume XXVIII marketplace Number Three chaplains caring for workers Marketplace is the magazine for Marketplace Ministries Inc., a non-profit, nondenominational Christian organization whose goal is to care for people in the workplace. Marketplace Ministries is able to operate because of the tax- deductible contributions made by people like you. In addition to letting you know how the ministry is progressing, Marketplace Ministries wants to thank you for enabling us to continue to care for people in the marketplace. Governing Board Foundation Board William R. Thomas, III Gil A. Stricklin Chairman Chairman, CEO & President Ed Bonneau Ed Bonneau Doug Fagerstrom Dan Farell Casey Gurganus Kyle Hearon Craig Hodges Mark Lovvorn 6 8 Neal Jeffrey, Jr. Calvin McKaig, MD Calvin McKaig, MD Ray Pace Andy Nace O.R. “Butch” Smith Phil Swatzell ——— Advisory Board ——— Tom Freet Ben March Chairman Nelson McKinney Jack Allen Phil McKinzie Pat Beckham Bob Osburn Carl Bolin Ray Pace Ted Raines Os Chrisman Louis Cole Del Rogers, Sr. Bill Crocker Bo Sexton Sam Forester Ann Sneed Gary Golden Ken Stohner, Jr. Ann Stricklin 2 10 Bruce Grantham Jerry Halcomb Charles Tandy, MD Patrick Hamner Greg Terrell Jim Harris James Williamson Jerry Wilson Steve Kerns HOW TO REACH US Bringing in the Harvest Headquarters 972-941-4400 2 Toll-Free 800-775-7657 Fax 972-578-5754 INTERNET ADDRESSES 6 North Carolina Chaplain Tony Wilson Awarded 2015 E-MAIL ADDRESS [email protected] Marketplace Chaplain of the Year [email protected] WEB SITE www.mchapusa.com www.marketplaceministries.com www.seniorlivingchaplains.com Training and Education — The Heartbeat of Marketplace 7 MARKETPLACE CHAPLAINS USA REGION OFFICE INFORMATION Ministries Eastern Region – Atlanta Shane Satterfield – Vice President 4485 Tench Rd.