Are Disclosures Really Standardized? an Empirical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 City of Mentor Visitor Guide

2020 CITY OF MENTOR VISITOR GUIDE Welcome to Mentor! With over 300 retailers and 170 eateries, the City of Mentor is at the heart of Lake County’s shopping, dining, and entertainment, experience. Whatever your taste, chances are pretty good that you’ll find it right here. The Mentor Visitor Guide offers up-to-date listings of where to eat, shop, play and stay in our city. Whether you are here for business or pleasure, we thank you for your visit and hope you enjoy your stay. Kenneth J. Filipiak City Manager BJ’s Restaurant & Brewhouse Fine Dining 7880 Mentor Ave., (440) 276-1360 Marion’s Restaurant & Tapas Bar ¯ 7701 Reynolds Rd., (440) 951-7100 Bob Evans Restaurants c 9232 Mentor Ave., (440) 205-9279 Molinari’s Food and Wine 7680 Reynolds Road, (440) 946-7117 8900 Mentor Ave., (440) 974-2750 Noosa Bistro Campola’s Italian Bistro ¯ 9500 Diamond Centre Dr., (440) 953-1088 7224 Center St., (440) 290-8676 Davitino’s Restaurant Pastina Rustic Italian ¯ 8820 Mentor Ave., (440) 266-0100 9354 Mentor Ave., (440) 290-8922 Denny’s Restaurant c Skye Bistro & Pub 7700 Mentor Ave., (440) 255-3154 8434 Mentor Ave., (440) 974-3572 Fridays 7814 Reynolds Road, (440) 953-2400 Casual Dining Kitchen, The c Aladdin’s Eatery 7519 Mentor Ave., (440) 510-8111 8870 Mentor Ave., (440) 205-5966 Lakeshore Eatery c Austin’s Wood Fire Grill (Coming Soon!) 7272 Lake Shore Blvd., (440) 946-3333 8748 Mentor Ave. Longhorn Steakhouse Applebee’s Neighborhood Grill 9557 Mentor Ave., (440) 639-5103 9174 Mentor Ave., (440) 974-3777 Mama Roberto’s Pizza & Pasta Baker’s Square c 8658 Mentor Ave., (440) 205-8890 7800 Plaza Blvd., (440) 255-6960 Manhattan Deli c Dickey’s Barbeque Pit 8900 Mentor Ave., (440) 974-0055 9434 Mentor Ave., (440) 809-8483 Market St. -

Restaurant Trends App

RESTAURANT TRENDS APP For any restaurant, Understanding the competitive landscape of your trade are is key when making location-based real estate and marketing decision. eSite has partnered with Restaurant Trends to develop a quick and easy to use tool, that allows restaurants to analyze how other restaurants in a study trade area of performing. The tool provides users with sales data and other performance indicators. The tool uses Restaurant Trends data which is the only continuous store-level research effort, tracking all major QSR (Quick Service) and FSR (Full Service) restaurant chains. Restaurant Trends has intelligence on over 190,000 stores in over 500 brands in every market in the United States. APP SPECIFICS: • Input: Select a point on the map or input an address, define the trade area in minute or miles (cannot exceed 3 miles or 6 minutes), and the restaurant • Output: List of chains within that category and trade area. List includes chain name, address, annual sales, market index, and national index. Additionally, a map is provided which displays the trade area and location of the chains within the category and trade area PRICE: • Option 1 – Transaction: $300/Report • Option 2 – Subscription: $15,000/License per year with unlimited reporting SAMPLE OUTPUT: CATEGORIES & BRANDS AVAILABLE: Asian Flame Broiler Chicken Wing Zone Asian honeygrow Chicken Wings To Go Asian Pei Wei Chicken Wingstop Asian Teriyaki Madness Chicken Zaxby's Asian Waba Grill Donuts/Bakery Dunkin' Donuts Chicken Big Chic Donuts/Bakery Tim Horton's Chicken -

Goplaysave Triangle 2020

GoPlaySave Triangle! • Over $10,500 in discounts from over 370 Local Triangle merchants • Discounts include “Buy One, Get One Free” and 50% Off • Merchants include Restaurants, Fun-Stuff & Shopping • Long Shelf Life - Coupons expire November 30, 2021 GoPlaySave Triangle 2020 - 2021 Participating Merchants Restaurants A Slice of NY Pizza Chocolate Fix HIGHTOP Burger Peak City Hots Stick Boy Bread Company Academy Street Bistro Chopstix Gourmet Chinese & Hog Heaven Bar-B-Q Pelican’s SnoBalls Subway Al’s Diner Sushi Restaurant Home Plate Restaurant & Penn Station Subs Sugar Koi Alfredo’s Pizza Village Chubby’s Tacos Catering Perri Brothers Pizza Sushi Siam Japanese & Ali Gator Snoballs Cilantro Indian Café Homegrown Pizza Persis Indian Grill Thai Restaurant Amante Gourmet Pizza Cinna Monster Honey Pig Pie-Zano’s Pizzeria Sweet Charlie’s Hand Rolled Amberly Local Cinnabon Honeybaked Ham Pizza Inn Ice Cream Amedeo’s Restaurant Clayton Steakhouse Hungry Howie’s Pizza Inn - Durham Sweet Frog Premium Frozen Up to $20 Value! American Hero Hillsborough Clean Eatz Hwy 54 Public House Pies & Pomodoro Italian Kitchen Yogurt Andia’s Homemade Ice Cream Coffee & Crepes Pints Pop’s Backdooor Pizza Sweet Spoons Frozen Yogurt Anna’s Pizzeria Coffee World Hwy 55 Burgers & Fries Pop’s Pizzeria & Ristorante Sweetheart Treats Apex Wings Restaurant & Pub Coldstone Creamery IHOP Potbelly Sandwich Shop TCBY Arby’s Common Grounds Coffee House Inchin’s Bamboo Garden Pretzel Maker Ashworth Pharmacy & Desserts J-Top’s BBQ Shop Pro’s Epicurean Market & Café Thanks A -

Kiosk Food Court Small Shop CONCOURSE LEASE PLAN

57th AVENUE Mall Address: QUEENS CENTER MALL 90-15 Queens Blvd. Food Court Elmhurst, NY 11373 FC01 CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS Phone: (718) 592-3901 FC02 KFC Fax: (718) 592-4157 h. ec M m FC03 PANDA EXPRESS oo R FC04 BOCBOC CHICKENDELICIOUS FC05 FIREHOUSE SUBS FC06 FAMOUS ROTISSERIE & GRILL For Leasing FC07 CHICK-FIL-A Information Contact: FC08 BIG EASY CAJUN Dustin Rand FC09 SBARRO FC10 SARKU JAPAN Morgan Liesenfelt FC11 MCDONALD'S 500 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2310 T FC12 CHIPOTLE MEXICAN GRILL New York, NY 10110 STORAGE E FC13 NOODLE HOUSE Phone: (212) 405-8800 E Mech. Room R T Small Shop S 0001 UP Mall Storage Special Lease storage 0024 QUAILS d 0061 SNAZZY CLOZET n 0050 2 ROOM 0025 9 TELE. SERVICE TELE. AT&T UP safe area AVAILABLE MODELL'S SPORTING GOODS STORAGE GAS METERS SECURITY STORAGE 0020 16,270 SF LOWER LEVEL 3,789 SF UPPER LEVEL H&M MEN'S SECURITY RR ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ELEC. SECURITY SECURITY CONTROL NER ROOM OFFICE OFFICE OFFICE TELCO WOMEN'S RR SECURITY RADIO ROOM ELEV. MACHINE ROOM RR ELEV. NO. N6 RR FREIGHT ELEVATOR CONTROL WOMENS N0. N5 LOCKER ROOM CONTROL MENS BREAK ROOM safesafe area area LOCKER ROOM K001 SLOP SINK STORAGE UP 1 . O N 2 . R O O N T A R L O P A T U C A S L O E A T C S E 2 P U 0 P U M O R 0 F Food Court K Office SPRINKLER RISER 0041 Janitor's NER Closet P U expansion FC08 FC09 FC10 FC11 FC12 joint Cafe 1058 Spice JIMMY JAZZ Storage 126 sf TELECOM FOREVER 21 ROOM CN 16,727 SF LOWER LEVEL 477SF Storage 11,340 SF UPPER LEVEL McDonalds ELEV. -

January 2020-Restaurant Inspections

City of St. Peters JANUARY 2020 Restaurant Inspections DATE SCORE ADDRESS SCORE 01/07/20 AGING AHEAD 108 MCMENAMY RD 100 01/27/20 AMVETS MEMORIAL POST #106 360 BROWN RD 100 01/02/20 APPLEBEE'S #8121 6170 MID RIVERS MALL DR 100 01/14/20 ARBY'S 5007032 225 MID RIVERS MALL DR 100 01/16/20 AUNTIE ANNE'S PRETZELS 1600 MID RIVERS MALL DR STE 2120 100 01/07/20 BANDANA'S BAR-B-Q 6163- MID RIVERS MALL DR 100 01/24/20 BANDANA'S BAR-B-QUE 4155 VETERANS MEMORIAL PKWY 98 01/31/20 BEN.E.FIT FITNESS & NUTRITION LLC 3004 S ST. PETERS PKWY STE A 100 01/06/20 BENTO SUSHI BAR @ DIERBERGS 6211 MID RIVERS MALL DR 100 01/24/20 BIG LOTS #1970 5881 SUEMANDY RD 100 01/09/20 BRICK OVEN, THE 84 SPENCER 94 01/24/20 BROOKDALE ST. PETERS 363 JUNGERMANN RD 98 01/28/20 CAKES BY GEORGIA, LLC 7338 MEXICO RD 100 01/15/20 CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS 1600 MID RIVERS MALL DR STE 1204 100 01/13/20 CHESTNUT GLEN-ASSISTED LIVING BY AMERICARE 121 KLONDIKE CROSSING 86 01/23/20 CHESTNUT GLEN-ASSISTED LIVING BY AMERICARE 121 KLONDIKE CROSSING 96 01/23/20 CHICKEN COOP 449 SOUTH CHURCH STREET 100 01/28/20 CHILI'S GRILL & BAR 101 MID RIVERS MALL CIR 96 01/02/20 CHOCOLATE CHOCOLATE CHOCOLATE CO. 6217 MID RIVERS MALL DR 100 01/26/20 CHURCH OF THE SHEPHERD 1601 WOODSTONE DR 100 01/30/20 CLUB DEMONSTRATION SERVICES, INC. -

SECOND 100 Chain Index

SECOND 100 Chain Index LATEST YEAR RANKINGS SYSTEM- % GROWTH, % GROWTH, % GROWTH, SALES WIDE SYSTEM NO. OF NO. OF NO. OF PER COMPANY HEADQUARTERS PARENT COMPANY SEGMENT SALES SALES UNITS UNITS FRAN. UNITS UNIT A&W All American Food Lexington, Ky. A Great American Brand LLC (A&W Restaurants Inc.) LSR/Burger 167 23 7 87 49 99 Au Bon Pain Boston LNK Partners LLC Bakery-Cafe 108 62 33 67 29 55 Bahama Breeze Orlando, Fla. Darden Restaurants Inc. Casual Dining 169 50 93 36 — 11 Baja Fresh Mexican Grill Irvine, Calif. BF Acquisition Holdings LLC LSR/Mexican 183 91 44 89 50 72 Bar Louie Addison, Texas Sun Capital Partners Inc. Casual Dining 157 19 57 7 5 36 Barnes & Noble Café New York Barnes & Noble Inc. In-Store 130 81 6 64 — 95 Beef 'O' Brady's Family Tampa, Fla. Levine Leichtman Capital Partners (FSC Franchise Co. LLC) Casual Dining 172 78 36 73 44 74 Sports Pub Benihana of Tokyo Miami Angelo, Gordon & Co. Casual Dining 125 74 75 66 56 19 Bertucci's Italian Restaurant Northborough, Mass. Jacobson Partners Casual Dining 180 76 67 63 — 41 Big Boy/Frisch's Big Boy Warren, Mich./Cin- Big Boy Restaurants International LLC/ Family Dining 110 63 29 77 54 59 cinnati NRD Capital Management LLC Black Bear Diner Redding, Calif. Black Bear Diners Inc. Family Dining 187 14 72 19 15 31 Braum's Ice Cream and Oklahoma City W.H. Braum Inc. LSR/Burger 145 54 24 48 — 81 Dairy Stores Brio Tuscan Grille Columbus, Ohio Bravo Brio Restaurant Group Inc. -

MANHATTAN Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

MANHATTAN Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results BUILDIN DBA STREET ZIPCODE G PARK AVENUE TAVERN 99 PARK AVENUE 10016 PARK AVENUE TAVERN 99 PARK AVENUE 10016 EL MITOTE 208 COLUMBUS AVENUE 10023 CROSSFIT SPOT 55 AMSTERDAM AVENUE 10023 DELIZIA 92 1762 2 AVENUE 10128 CAFE KATJA 79 ORCHARD STREET 10002 SATIN DOLLS 689 8 AVENUE 10036 HYATT, NY CENTRAL, ROOM SERVICE 0 & GRAND CENTRAL THE CHIPPED CUP 3610 BROADWAY 10031 KODAMA SUSHI 301 WEST 45 STREET 10036 CURRY IN A HURRY 119 LEXINGTON AVENUE 10016 GARDEN MARKET 4 PENN PLZ 10121 DEATH AVENUE BAR & GRIL 315 10 AVENUE 10001 CAFE 71 2061 BROADWAY 10023 CAFE KATJA 79 ORCHARD STREET 10002 STARBUCKS 2 COLUMBUS AVENUE 10019 BANK OF CHINA CAFETERIA 1045 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 10018 MILANES SPANISH RESTAURANT 168 WEST 25 STREET 10001 SMALLS JAZZ CLUB 183 WEST 10 STREET 10014 Page 1 of 478 10/01/2021 MANHATTAN Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results GRAD PHONE CUISINE DESCRIPTION E 2128674484 American A 2128674484 American A 2128742929 Mexican A 6463303791 Juice, Smoothies, Fruit Salads A 2129963720 Pizza A 2122199545 Eastern European A 2127655047 American A 6462136774 American A 9179519215 Coffee/Tea A 2125828065 Japanese A 2126830900 Indian A 2124656273 Hotdogs/Pretzels A 2126958080 American A 2128752100 Coffee/Tea A 2122199545 Eastern European A 2124896757 Coffee/Tea A 9172929468 Asian/Asian Fusion A 2122439797 Spanish A 6468230596 American A Page 2 of 478 10/01/2021 MANHATTAN Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results SHANGHAI MONG 30 WEST 32 -

Complete List of Stores Located at Newport Centre

Newport Centre 30 Mall Dr W Jersey City, NJ 07310 REGULAR CENTER HOURS PHONE NUMBERS Monday to Thursday 11:00AM - 8:00PM Friday to Saturday 10:00AM - 9:00PM Mall Office: Shopping Line: Mall Security: Sunday 12:00PM - 7:00PM (201) 626-2078 (201) 626-2025 (201) 626-2025 Store Name Store Phone # Mall Entrance Tip Location Info A Dollar Store (201) 876-4705 Use McDonald's Entrance/Park in West Garage between Sears Level 1 Sears wing directly next to and JC Penney Sears adidas (201) 963-3102 Use McDonald's Entrance/Park in the West Garage between Level 1 JCPenney wing next to Sears and JC Penney Kohesion Aeropostale (201) 795-0330 Park in West Garage between JCP and Sears. Use entrance on Located on level 2 next to Victoria's Level 2 Secret Aldo (201) 656-6744 Level 1 Entrance between Kohesion and McDonald's Level 1, JCPenney Wing AMC Theatre (888) 262-4386 Use McDonald's Entrance/Park in the West Garage between Level 3 Dining Pavilion on the left hand Sears and JC Penney side American Eagle Outfitters (201) 656-8386 Use McDonald's Entrance/ Park in the West Garage between Level 1 near Center Court in between Sears and JC Penney Bath & Body Works | White Barn and Charlotte Russe Art Mango AT&T (201) 876-7960 West Parking Garage located between JCP and Sears Level 2, located next to Clark's Atmosphere Use McDonald's Entrance next to Police Sub-Station/Park in West Level 1 next to Aldo Shoes Garage between Sears and JCPenney Auntie Anne's Pretzels - Kiosk (201) 222-9292 Use McDonald's Entrance Center Court across from Lids Auntie Anne's Pretzels - Store (201) 222-9292 Park in West Garage located between JCP and Sears. -

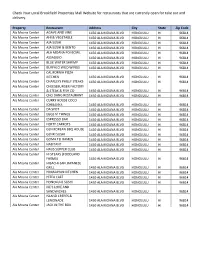

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for Restaurants That Are Currently Open for Take out and Delivery

Check Your Local Brookfield Properties Mall Website for restaurants that are currently open for take out and delivery. Property Restaurant Address City State Zip Code Ala Moana Center AGAVE AND VINE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AHI & VEGETABLE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center AJA SUSHI & BENTO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ALA MOANA POI BOWL 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ASSAGGIO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BLUE WATER SHRIMP 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center BUFFALO WILD WINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CALIFORNIA PIZZA KITCHEN 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHARLEYS PHILLY STEAKS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHEESEBURGER FACTORY & STEAK & FISH CO 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CHO DANG RESTAURANT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center CURRY HOUSE COCO ICHIBANYA 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center DA SPOT 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center EGGS N' THINGS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center ESPRESSO BAR 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center FORTY CARROTS 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GEN KOREAN BBQ HOUSE 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana Center GENKI SUSHI 1450 ALA MOANA BLVD HONOLULU HI 96814 Ala Moana -

NEARBY RESTAURANTS 100-185 New Hope Rd, Wellford, South Carolina, 29385, Drive Time of 10 Minutes

NEARBY RESTAURANTS 100-185 New Hope Rd, Wellford, South Carolina, 29385, Drive time of 10 minutes Distance Name Direction (Miles) SUBWAY SE 0.4 WAFFLE HOUSE SE 0.4 HOT DOG CAFE NW 2.1 SUBWAY NW 2.5 WENDY'S SW 2.6 FUDDRUCKERS SW 2.6 HARDEE'S SW 2.7 CHICK-FIL-A SW 2.7 SMOKIN WINGS T & T LLC SE 2.7 CRACKER BARREL OLD COUNTRY STR SW 2.7 ZAXBY'S CHICKEN FINGERS SW 2.7 WAFFLE HOUSE SW 2.7 TACO BELL SW 2.8 KFC SW 2.8 MC DONALD'S SW 2.8 Closest 15 locations This infographic contains data provided by Esri, Esri and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Esri and GfK MRI, Esri and Infogroup. The vintage of the data is 2020, 2025. © 2020 Esri NEARBY RESTAURANTS 100-185 New Hope Rd, Wellford, South Carolina, 29385, Drive time of 10 minutes Distance Name Direction (Miles) EL MOLCAJETE MEXICAN RSTRNT SW 2.8 BOJANGLES' FAMOUS CHICKEN SW 2.8 KINGZ OF WINGZ NW 2.8 PAISANOS SW 2.8 THAI CUISINE SW 2.8 EL PRIMO MEXICAN RESTAURANT SW 2.8 COUNTRY PRIDE RESTAURANT SW 2.9 FIREHOUSE SUBS SW 2.9 CLOCK OF LYMAN NW 2.9 SAKE GRILL SW 2.9 CLOCK FAMILY RESTAURANT SW 2.9 BUTCHER THE BAKER SW 2.9 MEHAR INC NE 3.0 LE SPICE SE 3.0 SUBWAY SW 3.0 Closest 15 locations This infographic contains data provided by Esri, Esri and Bureau of Labor Statistics, Esri and GfK MRI, Esri and Infogroup. -

Distance Dining | Rochester

Distance Dining | Rochester Restaurant Delivery Curbside/Pickup Website Address Phone $5 Pizza X X http://5dollarpizza.com 1105 7th Street NW (507) 258-5528 A & W All American Food X http://www.awrestaurants.com 202 Apache Mall (507) 288-1248 Applebee's Grill + Bar | Apache Mall X http://www.applebees.com 320 Apache Mall (507) 252-0155 Applebee's Grill + Bar | North X http://www.applebees.com 3794 Marketplace Drive NW (507) 280-6626 X Arby's | North http://www.arbys.com 2130 37th Street NW (507) 280-6104 X Arby's | South http://www.arbys.com 1218 Apache Drive SW (507) 281-2729 Auntie Anne's X http://www.auntieannes.com 101 1st Avenue SW (507) 281-1233 Bar Buffalo X X http://www.barbuffalomn.com/ 20 3rd Street SW (507) 258-6616 BB's Express X http://bbspizzaria.com/bbs-express/ 111 S Broadway (507) 424-0440 BB's Pizzaria X http://www.bbspizzaria.com 3456 E Circle Drive NE (507) 424-3366 Berry Blendz X http://www.berryblendz.com/ 2550 S Broadway (507) 536-0500 Bleu Duck Kitchen X http://www.bleuduckkitchen.com/ 14 4th Street SW (507) 258-4663 Broadway Bar & Pizza X X http://www.broadwaypizzarochester.com 4144 Highway 52 N (507) 208-4111 Bruegger's Bagels | North X http://www.brueggers.com 102 Elton Hills Drive NW (507) 287-6045 Buffalo Wild Wings | North X http://www.buffalowildwings.com 3458 55th Street NW (507) 536-0717 Buffalo Wild Wings | South X http://www.buffalowildwings.com 793 16th Street SW (507) 322-0501 Burger King | North X http://www.burgerking.com 1550 N Broadway (507) 285-1621 Burger King | Southeast X http://www.burgerking.com -

Franchising a Multibranding

Franchising a multibranding Mega / Multi/ Superfranchisor ▪ provozuje paralelně několik franchisových systémů ▪ obvykle se soustředí na jednu oblast podnikání ▪ nejen vývoj, ale i akvizice franchisových řetězce ▪ typicky hotelové či restaurační řetězce Příklady multifranchisorů v USA Yum! Brands, Inc. KFC Pizza Hut Taco Bell Mariott International, Inc. Mariott Sheraton Ritz-Carlton ▪ společnost provozuje 19 franchisových značek v oblasti služeb oprav a údržby ▪ Five Star Painting, Mr. Handyman, Mr. Electric, Molly Maid, Drain Doctor Plumbing a další ▪ Prezentace jednotlivých značek skupiny pod souhrnnou značkou NeighborlyTM Žebříček 200 TOP franchisových restaurací RANK COMPANY SYSTEM SALES U.S. LOCATION TOTAL LOCATION 1 McDonald´s $ 85,002,000,000 14,153 36,899 3 KFC $ 23,193,000,000 4,167 20,604 4 Burger King $ 18,209,200,000 7,156 15,738 5 Subway $ 17,000,000,000 26,741 45,936 7 Pizza Hut $ 12,019,000,000 7,667 16,411 9 Domino´s $ 10,900,000,000 5,371 13,811 11 Wendy´s $ 9,930,200,000 5,739 6,537 12 Taco Bell $ 9,656,000,000 6,278 6,604 14 Dunkin´ Donuts $ 8,933,300,000 8,828 12,258 Chick-fil-A $ 7,850,000,000 2,085 2,085 15 20 Tim Hortons $ 6,405,200,000 689 4,613 25 Panera Bread $ 5,177,739,000 2,017 2,036 zdroj: http://www.franchising.com Výhody multifranchisingu ▪ diverzifikace rizik a atraktivita pro investory ▪ silnější pozice při jednání s dodavateli a distributory ▪ větší podíl na trhu ▪ větší rovnováha hospodářských/ sezónních/ denních cyklů Multifranchisant ▪ vede paralelně více provozoven ▪ zpravidla ale ne výlučně v rámci jednoho franchisového systému ▪ větší efektivita, úspory nákladů Žebříček 99 TOP multi-franchisantů RANK COMPANY UNITS BRANDS 2018 1 NPC INTERNATIONAL 1.530 PIZZA HUT, WENDY'S 2 TARGET CORP.