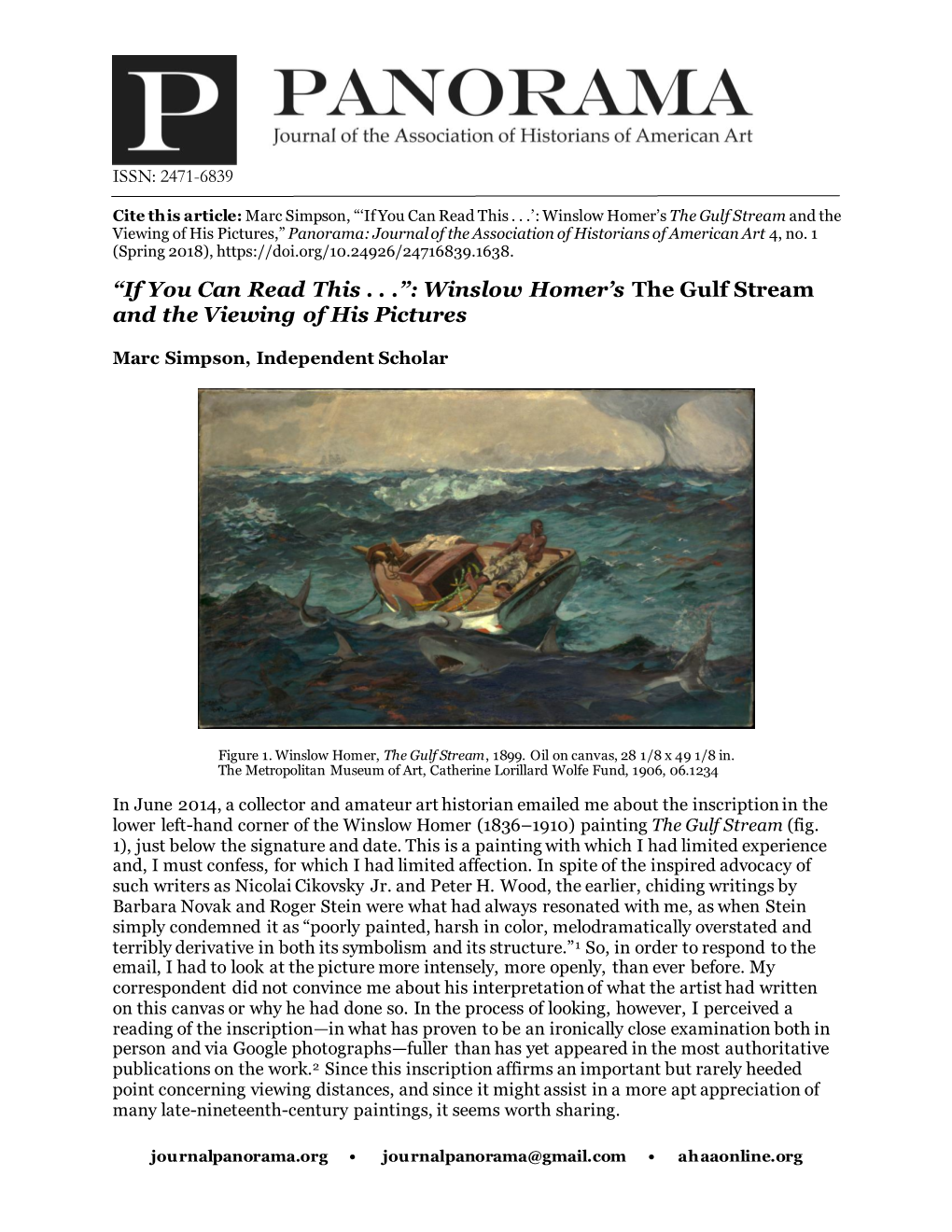

“If You Can Read This . . .”: Winslow Homer's the Gulf Stream and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Winslow Homer : New

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART WINSLOW HOMER MEMORIAL EXHIBITION MCMXI CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER OF THIS CATALOGUE AN EDITION OF 2^00 COPIES WAS PRINTED FEBRUARY, I 9 I I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/catalogueofloaneOOhome FISHING BOATS OFF SCARBOROUGH BY WINSLOW HOMER LENT BY ALEXANDER W. DRAKE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF A LOAN EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WINSLOW HOMER NEW YORK FEBRUARY THE SIXTH TO MARCH THE NINETEENTH MCMXI COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I 9 I I BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART LIST OF LENDERS National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts The Lotos Club Edward D. Adams Alexander W. Drake Louis Ettlinger Richard H. Ewart Hamilton Field Charles L. Freer Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Alexander C. Humphreys John G. Johnson Burton Mansfield Randall Morgan H. K. Pomroy Mrs. H. W. Rogers Lewis A. Stimson Edward T. Stotesbury Samuel Untermyer Mrs. Lawson Valentine W. A. White COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS John W. Alexander, Chairman Edwin H. Blashfield Bryson Burroughs William M. Chase Kenyon Cox Thomas W. Dewing Daniel C. French Charles W. Gould George A. Hearn Charles S. Homer Samuel Isham Roland F. Knoedler Will H. Low Francis D. Millet Edward Robinson J. Alden Weir : TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Frontispiece, Opposite Title-Page List of Lenders . Committee on Arrangements . viii Table of Contents .... ix Winslow Homer xi Paintings in Public Museums . xxi Bibliography ...... xxiii Catalogue Oil Paintings 3 Water Colors . • 2 7 Index ......... • 49 WINSLOW HOMER WINSLOW HOMER INSLOW HOMER was born in Boston, February 24, 1836. -

Handbook of the Collections

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Museum of Art Collection Catalogues Museum of Art 1981 Handbook of the Collections Bowdoin College. Museum of Art Margaret Burke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection- catalogs Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bowdoin College. Museum of Art and Burke, Margaret, "Handbook of the Collections" (1981). Museum of Art Collection Catalogues. 5. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection-catalogs/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum of Art at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Museum of Art Collection Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bowdoin College Museum of Art HANDBOOK of the Collections The Bowdoin College Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/handbookofcollecOObowd Handbook of the Collections Walter Art Building McKim, Mead & White, architects i8g2-i8g4 Bowdoin College Museum of Art HANDBOOK COLLECTIONS Edited by MARGARET R. BURKE BRUNSWICK, MAINE 1981 COVER DRAWING BASED ON ORNAMENTAL DETAILS OF THE WALKER ART BUILDING BY JOSEPH NICOLETTI TYPE COMPOSITION BY THE ANTHOENSEN PRESS OFFSET PRINTING BY THE MERIDEN GRAVURE COMPANY DESIGN BY JOHN McKEE This project is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C., a federal agency. ISBN: 0-916606-01-5 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81—66892 Copyright 1981 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved the memory ofJohn H. -

Three Centuries of American Painting

THREE CENTURIES OF AMERICAN PAINTING THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART APRIL 9 OCTOBER 17 THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM Cr ART AR C nI . For additional information about many of the paintings and pieces of sculpture in the exhibition, see the following; Available at The Metropolitan Museum Art and Book Shops. 1. Albert T. Gardner and Stuart P. Feld, American Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Volume One (covering paintings by artists born by 1815) (Metropolitan Museum, 1965). Cloth, $7.50. Paper, $2.95. Volumes Two and Three are in preparation. 2. Henry Geldzahler, American Paintina in the Twentieth Century (Metropolitan Muse 1965). Cloth, $7.50. Paper, $2.95. 3. Albert T. Gardner, American Sculpture (Metropolitan Museum, 1965). Cloth, $7.50. Paper, $2.95. 4. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, BULLETIN, April 1965. $.50 5. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Guide to the Collections, American Paintings, 1962, $.35 6. Edward Joseph Gallagher III Memorial Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, $.50 American paintings of the 17th, 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries are on exhibition in the Harry Payne Bingham Special Exhibition Galleries in the south wing (Wing K), second floor. American paintings of the 20th century are on exhibition in the Morgan Wing Galleries in the north wing (Wing F), second floor. ABBEY, Edwin Austin (1852-1911) K-9 AUDUBON, John James (1785-1851) K-5 King Lear's Daughters Ivory-billed Woodpeckers Dated 1898 Rogers Fund, 1941 Gift of George A. Hearn, 1913 13.140 41.18 ALBERS, Josef (1888- ) AUDUBON, John Woodhouse (1812-1862) and K-6 Homage to the Square: Precinct AUDUBON, Victor Giffordd809-1860) Datedl846 Dated 1951 Hudson's Bay Lemming George A. -

Scribner's Magazine

SCRIBNER’S MAGAZINE January, 1911 Volume 49, Issue 1 Important notice The MJP’s digital edition of the January 1911 issue of Scribner’s Magazine (49:1) is incomplete. It lacks the front and back covers of the magazine, the magazine’s table of contents, and all of the advertising that, in a typical issue of the magazine, could run for a hundred pages and appeared both before and after the magazine contents reproduced below. Because we were unable to locate an intact copy of this magazine, we made our scan from a six-month volume of Scribner’s (kindly provided to us by the John Hay Library, at Brown), from which all advertising was stripped when it was initially bound many years ago. For a better sense of what this magazine originally looked like, please refer to any issue in our collection of Scribner’s except for the following five incomplete issues: December 1910, January 1911, August 1911, July 1912, and August 1912. If you happen to know where we may find an intact, cover-to-cover hard copy of any of these five issues, we would appreciate if you would contact the MJP project manager at: [email protected] Drawn by Blendon Campbell. SO THE SAD SHEPHERD THANKED THEM FOR THEIR ENTERTAINMENT AND TOOK THF LITTLE KID AGAIN IN HIS ARMS, AND WENT INTO THE NIGHT. —"The Sad Shepherd," page 7. SCRIBNER'S MAGAZINE VOL. XLIX JANUARY, 1911 NO. 1 THE SAD SHEPHERD BY HENRY VAX DYKE ILLUSTRATION* (FRONTISPIECE) BY BLENDON CAMPBELL I among the copses fell too far behind, he drew out his shepherd's pipe and blew a OUT of the Valley of Gardens, strain of music, shrill and plaintive, qua• where a film of new-fallen vering and lamenting through the hollow snow lay smooth as feathers night. -

The Story of Prouts Neck

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 1924 The Story of Prouts Neck Rupert Sargent Holland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Genealogy Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Holland, Rupert Sargent, "The Story of Prouts Neck" (1924). Maine Collection. 101. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·THE STORY OF PROUTS NECK· BY RUPERT SARGENT HOLLAND .. THE PROUTS NECK ASSOCIATION PROUTS NECK, MAINE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF FRANK MOSS ARTIST AND DEVOTED WORKER FOR THE WELFARE OF PROUTS NECK .. Copyright 1924 by The Prouts Neck Association Prouts Neck, Me. Printed in U.S. A. THE COSMOS PRESS, INC., CAMBRIDGE, MASS. The idea of collecting and putting in book form sotrie of the interesting incidents in the history of Prouts Neck originated with Mr. Frank Moss, who some years ago printed for private distribution an account of the N~ck as it was in I886 and some of the changes that had since occurred. Copies of this pamphlet were rare, and Mr. Moss and some of his friends wished .to add other material of interest and bring it up to date, making a book that, published by the Prouts Neck Association, should interest summer residents ·in the story of this beautiful headland and in the endeavors to preserve its native charms. -

The Life and Works of Winslow Homer

i^','i yv^ ijj.B.CLARK£ cn Qni'5;tLL£RS«ST»Tm..ri THE LIFE AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER PORTIL^IT OF WINSLOW HOMER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTY-TWO From a photograph taken at Prout's Neck, Maine, in igo8. Photogravure 1 y^ff THE'T'ttt:^ LIFEt ti AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 191 JNJMAA/j«^G LIBRARY JUL 19™ i5[!15WW OCT 2 :M332 iNSTITUTlOW HATiOMAL COLL^^iiuji Of FINE AHW COPYRIGHT^ J911, BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES ALL RIGHTS RESER\'ED Published October iqii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THE author is grateful to all those persons who have aided him in the preparation of this biography. To Winslow Homer's two brothers he owes especially cordial thanks. Mr. Charles S. Homer has been most kind in lending indispensable assistance and most patient in an- swering questions. Mr. Arthur B. Homer with fortitude has listened to the reading of the entire manuscript, and has given wise and valuable counsel and criticism. To Mr. Arthur P. Homer and Mr. Charles Lowell Homer of Boston the author is indebted for many useful suggestions and interesting remi- niscences. Mr. Joseph E. Baker, the friend and comrade of Winslow Homer in his youth, and his fellow-apprentice in BufTord's lithographic establishment in Boston, from 185510 1857, has supplied interesting data which could have been obtained from no other source. Mr. Walter Rowlands, of the fine arts department of the Boston Public Library, has made himself useful in the line of historic research, for which his experience admirably qualifies him, and has gone over the first rough draft of the manuscript and offered many friendly hints and suggestions for its betterment. -

Oncise Catalogue O

oncise catalogue o in THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART A Concise Catalogue of the AMERICAN PAINTINGS in THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART COMPILED BY Albert Ten Eyck Gardner, Associate Curator of American Art NEW YORK 1957 Foreword This concise catalogue has been prepared in answer to a continuing de mand for a complete list of the Museum's collection of American paintings. It is the aim of the catalogue to give only the essential information about paintings in oil by American artists. The paintings are listed alphabeti cally by artist; measurements are given in inches, height preceding width; signatures and some inscriptions have been transcribed. All paintings acquired through December 1956 have been included. An asterisk on an entry indicates a subject received in exchange for an earlier acquisition. A detailed catalogue of American paintings, now in preparation, will be issued in due course. The compiler wishes to thank Mrs. Herbert Iselin for adding recent acquis itions to the catalogue, and Mrs. Josephine L. Allen and Mrs. Gardner for checking entries and correcting proofs. A. T. G. Catalogue Study in Black and Green Oil on canvas, 40x50 in. Signed (lower left): J. W. Alexander George A. Hearn Fund, 1908. 08.139.1 A Walt Whitman (1819-1892) Oil on canvas, 50x40 in. Signed and dated (lower right): American, Artist Unknown J. W. Alexander-89 XVIII century, second quarter Gift of Mrs. Jeremiah Milbank, 1891. 91.18 Thomas Nelson of Virginia (?) Oil on canvas, 46x36 in. Allen, Junius 1898- Source unknown. X.101 The Old New York Post Office Oil on canvas, 36x42 in. -

Catalogue of Paintings

pi lliliiill, COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE LIBRARY Cornell University Library N 610.A65 1920 Catalogue of paintings / 3 1924 020 595 173 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924020595173 THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF PAINTINGS MCMXX CATALOGUE OF PAINTINGS VIRGIN ENTHRONED WITH SAINTS BY RAPHAEL THE METROPOLITAM MUSEUM OF ART CATALOGUE OF PAINTINGS BY BRYSON BURROUGHS CURATOR , DEPARTMENT OF PAINTINGS FIFTH EDITION NEW YORK M C M X X hr 33^t| FIRST EDITION, COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I9I4 SECOND EDITION, COPYRIGHT, FEBRUARY, I916 THIRD EDITION, COPYRIGHT, JUNE, I917 FOURTH EDITION, COPYRIGHT, MARCH, I919 FIFTH EDITION, COPYRIGHT, JUNE, I92O BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART PREFACE alphabetical arrangement by the names of artists, or by AN schools where the artists are unknown, is followed in this . book. In the attempt to solve the problem of number- ^ ing a rapidly growing collection of paintings, the experi- ment has been made here of adapting the C. A. Cutter system, long in use in libraries. To use the catalogue it is not necessary to be familiar with the system of numbering, but for those who may be interested an explanation follows. It consists of a combination of letters and numbers, composed of the initial letter of the author's name followed by numbers that represent the succeeding letters of the same, so that additional entries can be inserted without disturbing the sequence of the letters or the numerals. -

WINSLOW HOMER an American Painter

WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Dr. Ufuk ÇETİN WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter Author: Ufuk Çetin ORCID (0000-0001-5102-8183) ISBN: 978-625-7729-02-4 E-ISBN: 978-625-7729-03-1 First Edition: September 2020 © 2020 Efe Akademi. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mecha- nical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or a magazine. LIBRARY CATALOG ÇETİN, Ufuk Winslow Homer An American Painter First Edition, p. 71 , 135 x 195 mm. Keywords: 1. Painting, 2. American Painting Art, 3. .19th Century, 4. Landscape Painting, 5. Sea Painting. Graphic Design: İsa Burak GÜNGÖR ([email protected]) Cover Design: Duygu DÜNDAR ([email protected]) Certificate No: 43370 Printing House Certificate No: 43370 Efe Akademi Yayınevi Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 482 22 00 www.efeakademi.com Printing House: Ofis2005 Fotokopi ve Büro Makineleri San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Davutpaşa Kampüsiçi Esenler / İSTANBUL +90212 483 13 13 www.ofis2005.com WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter This book was written by me for my respected Professor Dr. Engin Beksaç for all his researches and studies in all forms of art through great passion just a present. Dr. Ufuk Çetin 20.09.2020 3 Ufuk Çetin 4 WINSLOW HOMER An American Painter TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 11 HIS CHILDHOOD AND ARTISTIC CAREER ........ 18 SOME EXAMPLES FROM HIS PAINTINGS......... -

Gorham Munson WINSLOW HOMER of PROUT's NECK, :MAINE

Gorham Munson -' WINSLOW HOMER OF PROUT'S NECK, :MAINE THE WINSLOW HoMER retrospect exhibition at the National Gallery of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in late 1958 and early 1959 was an incite ment to reappraisals of the Maine painter. The point was repeatedly made that Homer, like Manet, has survived his century and is a modern; we were told that we must not regard him as a painter of the Gilded Age but as a master of art in the Twentieth Century. In what consists the modernity of Winslow Homer? First of all, in his originality. In his apprenticeship, Homer stated: "If a man wants to be an artist, he should never look at pictures". This youthful dictum used to perplex the critics but time has caught up with the independent spirit it dis played, and to a modern, Homer's meaning is clear. He meant simply that the artist should turn away from the academic tradition and see things afresh. At the outset of his career he knew for a truth what his contemporary, the essayist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, would later say: "Originality is simply a pair of fresh eyes." A second modern trait of Homer's was observed-and disliked-by Henry James. "The artist", he said of Homer, "turns his back squarely and frankly upon literature". But his subjects!-"to the eye, he is horribly ugly". "We frankly confess", James said in the Galaxy in 1875, "that we detest his subjects-his barren plank fences, his glaring, bold, blue skies, his big dreary lots of meadows, his freckled, straight-haired Yankee urchins, his flat-breasted maidens, suggestive of a dish of rural doughnuts and pie, his calico sun-bonnets, his flannel shirts, his cowhide boots.