Balancing Freedom of the Press and Reasonable Restrictions In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

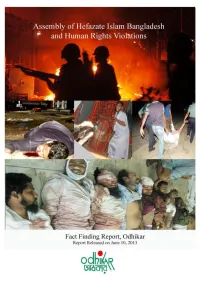

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Women Leadership in Decentralised Governance and Rural Development: a Study of Selected Union Parishads of Kushtia District in Bangladesh (1997-2003)

Women Leadership in Decentralised Governance and Rural Development: A Study of Selected Union Parishads of Kushtia District in Bangladesh (1997-2003) THESIS SUBMinED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOOOR OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS) AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL MD. AMANUR RAHMAN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROFESSOR M. YASIN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL DARJEELING INDIA 2010 il'\~ 6 9 hJ &6 P.S 't~Q oft7 t ·LQCC, ~ Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to place on record my deepest sense of gratitude and sincere thanks to my supervisor Dr. M. Y asin, Professor of Political Science, University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India. I am deeply indebted to him for guiding and supervising this work and providing unending inspiration, persistent encouragement that have led to smooth completion my dissertation. He has taken much pain to supervise my thesis with utmost care and attention. I am beholden to the authority of the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India for giving me the opportunity to carry out the research work. Grateful acknowledgement is due to my teacher Professor Dr. M Alauddin, Hon' able Vice-Chancellor of Islamic University, Kushtia, Bangladesh who always inspired me to stay at the field of research and always wishes for my success. I am grateful to my teacher distinguished folklorist Professor Dr. Abul Ahsan Choudhury of the Department of Bengali, Islamic University, Kushtia, Bangladesh who has virtually led me to the road to research. I am equally grateful to Professor Dr. P.K Sengupta, Department of Political Science, University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India, Professor Dr. -

1 Introduction

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

Students, Space, and the State in East Pakistan/Bangladesh 1952-1990

1 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 A dissertation presented by Samantha M. R. Christiansen to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts September, 2012 2 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 by Samantha M. R. Christiansen ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University September, 2012 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of East Pakistan/Bangladesh’s student movements in the postcolonial period. The principal argument is that the major student mobilizations of Dhaka University are evidence of an active student engagement with shared symbols and rituals across time and that the campus space itself has served as the linchpin of this movement culture. The category of “student” developed into a distinct political class that was deeply tied to a concept of local place in the campus; however, the idea of “student” as a collective identity also provided a means of ideological engagement with a globally imagined community of “students.” Thus, this manuscript examines the case study of student mobilizations at Dhaka University in various geographic scales, demonstrating the levels of local, national and global as complementary and interdependent components of social movement culture. The project contributes to understandings of Pakistan and Bangladesh’s political and social history in the united and divided period, as well as provides a platform for analyzing the historical relationship between social movements and geography that is informative to a wide range of disciplines. -

Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops

Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops 9 Bangladesh Strategizing Communication in Commercialization of Biotech Crops Khondoker M. Nasiruddin angladesh is on the verge of adopting genetically modified (GM) crops for commercial cultivation and consumption as feed and Bfood. Many laboratories are engaged in tissue culture and molecular characterization of plants, whereas some have started GM research despite shortage of trained manpower, infrastructure, and funding. Nutritionally improved Golden Rice, Bt brinjal, and late blight resistant potato are in contained trial in glasshouses while papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) resistant papaya is under approval process for field trial. The government has taken initiatives to support GM research which include the establishment of a Biotechnology Department in all relevant institutes, and the formation of an apex body referred to as the National Task Force Chapter 9 203 Khondoker M. Nasiruddin he world’s largest delta, Bangladesh BANGLADESH is a very small country in Asia with Tonly 55,598 square miles of land. It is between India which borders almost two-thirds of the territory, and is bounded by Burma to TRY PROFILE TRY the east and south and Nepal to the north. N Despite being small in size, it is home to nearly 130 million people with a population density COU of nearly 2000 per square miles, one of the highest in the world. About 85% live in rural villages and 15% in the urban areas. The country is agricultural where 80% of the people depend on this industry. Fertile alluvial soil of the Ganges- Meghna-Brahmaputra delta coupled with high rainfall and easy cultivation favor agricultural development (Choudhury and Islam, 2002). -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

Factors That Push Bangladeshi Media to Exercise Self-Censorship

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2020 Factors That Push Bangladeshi Media to Exercise Self-Censorship Abu Taib Ahmed University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ahmed, Abu Taib, "Factors That Push Bangladeshi Media to Exercise Self-Censorship" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2445. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2445 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTORS THAT PUSH BANGLADESHI MEDIA TO EXERCISE SELF-CENSORSHIP by Abu Taib Ahmed A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2020 ABSTRACT FACTORS THAT PUSH BANGLADESHI MEDIA TO EXERCISE SELF-CENSORSHIP by Abu Taib Ahmed The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2020 Under the Supervision of Professor David S. Allen Self-censorship is one of the biggest threats to press freedom. Press freedom, as well as freedom of the expression, is an indicator of a society’s freedom and democracy. If the media cannot act freely, it can impact society’s ability to function as a democracy. Journalists often face pressures from various power structures to engage in self-censorship. While journalistic self- censorship has been examined in a number of different countries, no studies of journalistic self- censorship in Bangladesh have been undertaken or no studies have been undertaken to see what factors influence journalists to exercise self-censorship or to figure out reasons that make journalists in Bangladesh filter media content. -

Concert for Migrants’ at a Glance: to Celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a Virtual Concert Titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ Was Organized on 18 December 2020

‘Concert for Migrants’ at A Glance: To celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a virtual concert titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ was organized on 18 December 2020. Featuring popular singers from home and abroad, the concert has reached more than 3.3 million people in more than 30 countries worldwide. In between performing a range of popular songs, the celebrities spoke on the importance of informed migration decisions contributing to regular, safe, and orderly migration, sustainable reintegration as well as migration governance. Outreach of the Concert Number of people reached online 1.9 Million Number of people watched the concert on TV 1.4 Million Total 3.3 Million Name of the top 15 countries from where Bangladesh, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Qatar, Lebanon, Kuwait, people watched the concert Bahrain, Jordan, Malaysia, Singapore, UK, Egypt, Italy, and Japan Number of media report produced 37+ A number of creative content were developed and shared on our social media platforms with the endorsement of celebrities. Video messages of the singers: • Fahmida Nabi: https://fb.watch/2Nh7wL_j-c/ • Sania Sultana Liza: https://fb.watch/2Nh5OeaFrB/ • S.I. Tutul: https://fb.watch/2Nh6HEtrjW/ • Sahos Mostafiz: https://fb.watch/2NhdDW4VBj/ • Fakir Shabuddin: https://fb.watch/2NhavHLAXI/ • Xefer Rahman: https://fb.watch/2NhfsHFkb2/ • Polash Noor: https://fb.watch/2Nh3fURc-Z/ • Nowshad Ferdous: https://fb.watch/2NhgfU2SfA/ • Mizan Mahmud Razib: https://fb.watch/2Nh9_iwehf/ Promo: https://fb.watch/2NhcsD5lRB/ Media Reports on the Concert: 1. Daily Star 11. Daily Asian Age 21. Dainik Amader Shomoy 31. Barta 24 2. Dhaka Tribune 12. Daily Ittefaq 22. Newshunt 32. Change 24 3. -

Sensitive Space Along the India-Bangladesh Border

THE FRAGMENTS AND THEIR NATION(S): SENSITIVE SPACE ALONG THE INDIA-BANGLADESH BORDER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Cons January 2011 © 2011 Jason Cons THE FRAGMENTS AND THEIR NATION(S): SENSITIVE SPACE ALONG THE INDIA-BANGLADESH BORDER Jason Cons, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 Borders are often described as “sensitive” areas—exceptional and dangerous spaces at once central to national imaginaries and at the limits of state control. Yet what does sensitivity mean for those who live in, and those who are in charge of regulating, such spaces? Why do these areas persist as spaces of conflict and confusion? This dissertation explores these questions in relation to a series of enclaves—sovereign pieces of India inside of Bangladesh and vice versa—clustered along the Northern India–Bangladesh border. In it, I develop the notion of “sensitivity” as an analytic for understanding spaces like the enclaves, showing how they are zones within which postcolonial fears about sovereignty, security, identity, and national survival become mapped onto territory. I outline the politics of sensitivity and the production of sensitive space through both historical and ethnographic research. First, I explore the ways that ambiguity and vague fears about security and citizenship emerge as forms of moral regulation within and in relation to the enclaves. Specifically, I interrogate the processes through which information about the enclaves is regulated and policed and the ambiguity, suspicion, and insecurity that emerge out of such practices. -

Download China’S Economic Diplomacy Towards ?Doi=10.1.1.611.3348&Rep=Rep1&Type=Pdf South Asia

British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1(4), 1-13, 2019 Publisher homepage: www.universepg.com, ISSN: 2663-7782 (Online) & 2663-7774 (Print) https://doi.org/10.34104/bjah.019.1013 British Journal of Arts and Humanities Journal homepage: www.universepg.com/journal/bjah Bangladesh-East Asia Relations in the Context of Bangladesh’s Look East Policy Akkas Ahamed1, Md. Masum Sikdar2*, and Sonia Shirin3 1Dept. of Political Science, University of Chittagong, Chittagong, Bangladesh; 2Dept. of Political Science, University of Barisal, Barisal, Bangladesh; and 3Dept. of English, Gono Bishwabidyalay, Dhaka, Bangladesh. *Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT 'Look East' diplomacy and its foreign policy aspiration of engagement with East Asian countries is part of clear recognition of strategic and economic importance of the region to Bangladesh's national interests. Bangladesh government is planning to implement the 65,000 kilometer road project through Asian highway route. Bangladesh would be linked to 15 countries with the proposed road network. The Asian Highway plan was first launched in 1959 under UN Economic, and Social Commission for South Asia, and Pacific (ESCAP). Its main purpose is to increase regional and international cooperation between Asia, and Europe via Turkey and to set transportation, infrastructural progress for socio-economic development of many countries in the region. In order to realize Bangladesh’s potential and expedite further growth, Japan has come up with the concept of the Bay of Bengal industrial growth belt” or what Prime Minister Shinzu Abe termed “The BIG-B”. On the other hand, Chinese President Xi Jinping narrate Bangladesh as an emerging country along the “Maritime Silk Road” (MSR) project that he has been championing, which envisages deepening connectivity, constructing ports, free trade sectors, and boosting trade with littoral countries in the Indian Ocean zone, and in East Asia. -

The Use of Excessive Force During Bangladesh Protests WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS BLOOD ON THE STREETS The Use of Excessive Force during Bangladesh Protests WATCH Blood on the Streets The Use of Excessive Force during Bangladesh Protests Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-30404 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2013 978-1-6231-30404 Blood on the Streets The Use of Excessive Force during Bangladesh Protests Map of Bangladesh ...................................................................................................................... i Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

BANGLADESH: from AUTOCRACY to DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values)

BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 Professor PARK, Hun-Joo (David) ABSTRACT BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY By Golam Shafiuddin The political history of independent Bangladesh is the history of authoritarianism, argument of force, seizure of power, rigged elections, and legitimacy crisis. It is also a history of sustained campaigns for democracy that claimed hundreds of lives. Extremely repressive measures taken by the authoritarian rulers could seldom suppress, or even weaken, the movement for the restoration of constitutionalism. At times the means adopted by the rulers to split the opposition, create a democratic facade, and confuse the people seemingly served the rulers’ purpose. But these definitely caused disenchantment among the politically conscious people and strengthened their commitment to resistance. The main problems of Bangladesh are now the lack of national consensus, violence in the politics, hartal (strike) culture, crimes sponsored with political ends etc. which contribute to the negation of democracy. Besides, abject poverty and illiteracy also does not make it easy for the democracy to flourish. After the creation of non-partisan caretaker government, the chief responsibility of the said government was only to run the routine administration and take all necessary measures to hold free and fair parliamentary elections.