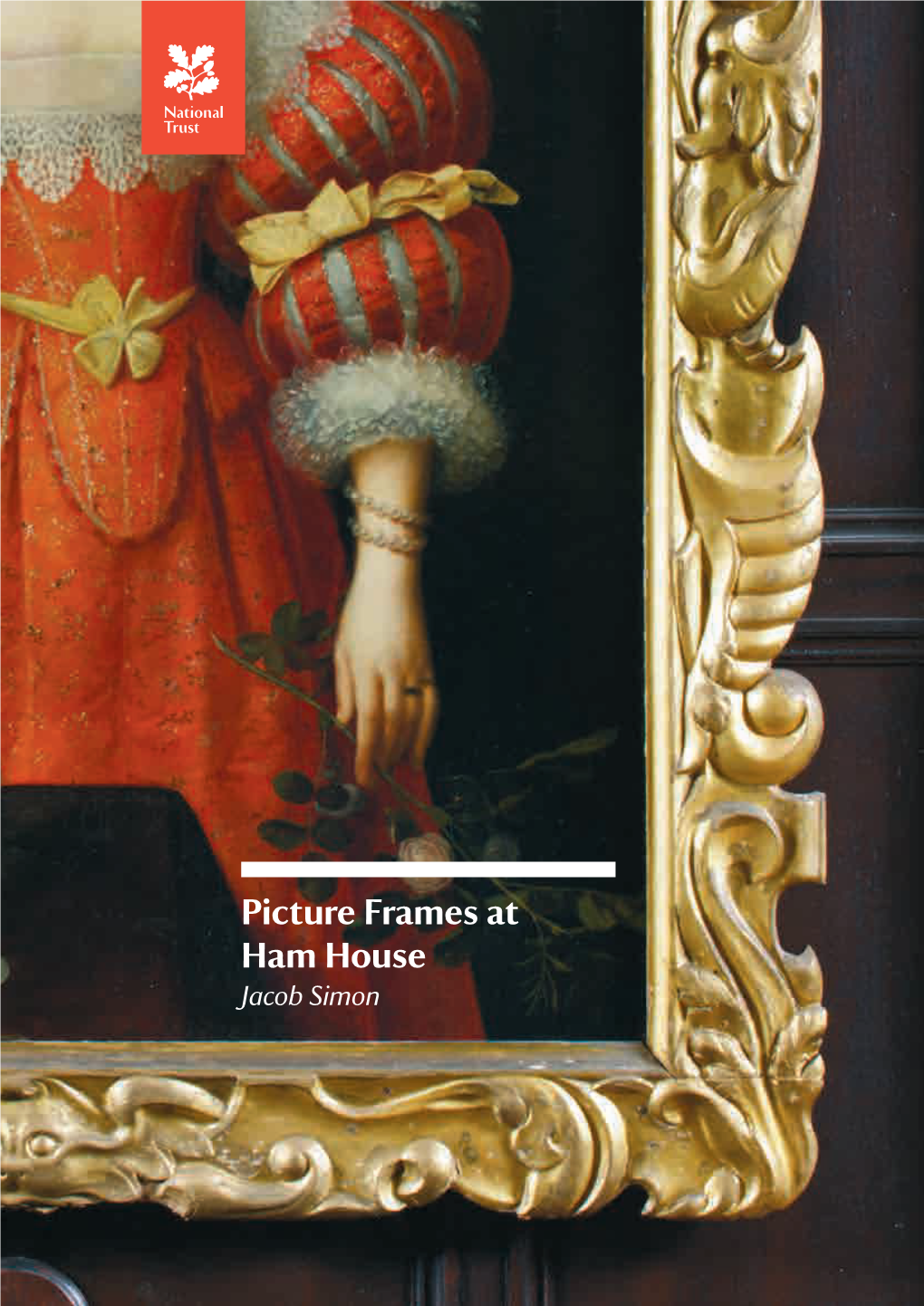

Picture Frames at Ham House Jacob Simon Picture Frames at Ham House by Jacob Simon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marble Hill Revived

MARBLE HILL REVIVED Business Plan February 2017 7 Straiton View Straiton Business Park Loanhead, Midlothian EH20 9QZ T. 0131 440 6750 F. 0131 440 6751 E. [email protected] www.jura-consultants.co.uk CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary 1.0 About the Organisation 1. 2.0 Development of the Project 7. 3.0 Strategic Context 17. 4.0 Project Details 25. 5.0 Market Analysis 37. 6.0 Forecast Visitor Numbers 53. 7.0 Financial Appraisal 60. 8.0 Management and Staffing 84. 9.0 Risk Analysis 88. 10.0 Monitoring and Evaluation 94. 11.0 Organisational Impact 98. Appendix A Project Structure A.1 Appendix B Comparator Analysis A.3 Appendix C Competitor Analysis A.13 Marble Hill Revived Business Plan E.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E1.1 Introduction The Marble Hill Revised Project is an ambitious attempt to re-energise an under-funded local park which is well used by a significant proportion of very local residents, but which currently does very little to capitalise on its extremely rich heritage, and the untapped potential that this provides. The project is ambitious for a number of reasons – but in terms of this Business Plan, most importantly because it will provide a complete step change in the level of commercial activity onsite. Turnover will increase onsite fourfold to around £1m p.a. as a direct result of the project , and expenditure will increase by around a third. This Business Plan provides a detailed assessment of the forecast operational performance of Marble Hill House and Park under the project. -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

The Earlier Parks Charles I's New Park

The Creation of Richmond Park by The Monarchy and early years © he Richmond Park of today is the fifth royal park associated with belonging to the Crown (including of course had rights in Petersham Lodge (at “New Park” at the presence of the royal family in Richmond (or Shene as it used the old New Park of Shene), but also the Commons. In 1632 he the foot of what is now Petersham in 1708, to be called). buying an extra 33 acres from the local had a surveyor, Nicholas Star and Garter Hill), the engraved by J. Kip for Britannia Illustrata T inhabitants, he created Park no 4 – Lane, prepare a map of former Petersham manor from a drawing by The Earlier Parks today the “Old Deer Park” and much the lands he was thinking house. Carlile’s wife Joan Lawrence Knyff. “Henry VIII’s Mound” At the time of the Domesday survey (1085) Shene was part of the former of the southern part of Kew Gardens. to enclose, showing their was a talented painter, can be seen on the left Anglo-Saxon royal township of Kingston. King Henry I in the early The park was completed by 1606, with ownership. The map who produced a view of a and Hatch Court, the forerunner of Sudbrook twelfth century separated Shene and Kew to form a separate “manor of a hunting lodge shows that the King hunting party in the new James I of England and Park, at the top right Shene”, which he granted to a Norman supporter. The manor house was built in the centre of VI of Scotland, David had no claim to at least Richmond Park. -

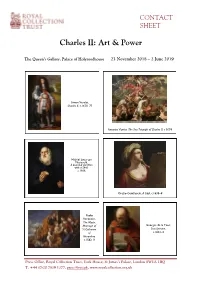

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

A Suit of Silver: the Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century

Costume, vol. 48, no. 1, 2014 A Suit of Silver: The Underdress of a Knight of the Garter in the Late Seventeenth Century By D W This paper describes the cut and construction of the doublet and hose worn as underdress to the robes and insignia of the Knights of the Most Noble Order of the Garter at the English Court under Charles II. This example belonged to Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. It is interesting on several counts: the dominant textile is a very pure cloth of silver; the elaborate hose are constructed with reference to earlier seventeenth-century models; the garments exemplify Charles II’s understanding of the importance of ceremony to successful kingship. The suit was conserved for an exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the essay gives some account of discoveries made through this process. In addition, the garments are placed in the context of late seventeenth- century dress. : Charles II, Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond, Order of the Garter, ceremonial dress, seventeenth-century men’s clothing, seventeenth-century tailoring T N M S, Edinburgh, UK has in its possession a set of clothes comprising a late seventeenth-century ceremonial doublet and trunk hose, part of the underdress of the robes of the Order of the Garter (Figures 1 and 2).1 The garments are made of cloth of silver and were once worn by Charles Stuart, sixth Duke of Lennox and third Duke of Richmond (1639–1672), who was created a knight of the Garter in 1661. -

S 11 T Is Ii Nn 1N 1101 In

s 11 T i s ii n n H- w 3 £ 1n 1101 i n <W O W hf Washington 25, D.C NEWS RELEASE DATE For release July 11, 1962 Washington,. D.C., July 11, 1962. The Traveling Exhibition Service of the Smithsonian Institution announced today a forthcoming exhibition of major importance, "Old Master Drawings from Chatsworth," which will open at the National Gallery of Art on October 28th. The lik magnificent drawings which comprise the exhibition are on loan from one of the finest private art collections in England, formed by the second Duke of Devonshire in the late 17th and early l8th centuries and enlarged by his descendants. Selected by Mr. A. E. Popham, for many years Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, they illustrate the art of drawing in Europe from the Renaissance to the end of the 17th century. Chatsworth is one of the most famous of the great British country houses, and only on two occasions has an exhibition representing its wealth of drawings been attempted. Both were in England. Perhaps the outstanding feature of the collection is the series of landscape drawings by Rembrandt, ten of which are to be shown. Among the kj other artists represented are Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Giulio Romano, Mantegna, Correggio, Parmigianino, Primaticcio, Veronese, Rosso, Bruegel, Van i) ~~ Dyck, Rubens^ Durer, Holbein, and Inigo Jones. The earliest drawing in the exhibition is by an anonymous 15th century Sienese artist showing the "Betrayal of Christ" on one side and a finished composition representing "Christ Before the High Priest" on the reverse. -

1 Aldred/Nattes/RS Corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1

1 Tittler Roberts:1 Aldred/Nattes/RS corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1 Volume XI, No. 2 The BRITISH ART Journal Discovering ‘T. Leigh’ Tracking the elusive portrait painter through Stuart England and Wales1 Stephanie Roberts & Robert Tittler 1 Robert Davies III of Gwysaney by Thomas Leigh, 1643. Oil on canvas, 69 x 59 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff. With permission of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales n a 1941 edition of The Oxford Journal, Maurice 2 David, 1st Earl Barrymore by Thomas Leigh, 1636. Oil on canvas, 88 x 81 Brockwell, then Curator of the Cook Collection at cm. Current location unknown © Christie’s Images Ltd 2008 IDoughty House in Richmond, Surrey, submitted the fol- lowing appeal for information: [Brockwell’s] vast amount of data may not amount to much T. LEIGH, PORTRAIT-PAINTER, 1643. Information is sought in fact,’5 but both agreed that the little available information regarding the obscure English portrait-painter T. Leigh, who on Leigh was worth preserving nonetheless. Regrettably, signed, dated and suitably inscribed a very limited number of Brockwell’s original notes are lost to us today, and since then pictures – and all in 1643. It is strange that we still know nothing no real attempt has been made to further identify Leigh, until about his origin, place and date of birth, residence, marriage and now. death… Much research proves that the biographical facts Brockwell eventually sold the portrait of Robert Davies to regarding T. Leigh recited in the Burlington Magazine, 1916, xxix, the National Museum of Wales in 1948, thus bringing p.3 74, and in Thieme Becker’s Allgemeines Lexikon of 1928 are ‘Thomas Leigh’ to national attention as a painter of mid-17th too scanty and not completely accurate. -

Surrey. Petersham

[)JRECTORY. J SURREY. PETERSHAM. 343 dent on pew rents about £154, in the gift of the Bishop of are also many valuable portraits and paintings, in excellent Southwark, and held since 1891 by the Rev. William Henry preservation, representing characters of note and various Oxley lii.A. of St. John's College, Oxford, and surrogate: the ancestors of the present family : John, second Dllke of impropriate tithe, about £50 yearly, belongs to the Earl of Argyll, was born here in 1678: James II. was ordered to Dysart. The vicarage house, a. structure of red brick. was retire here before he abdicated: the manor belonged to built by private subscription in 1889 and has since been en Chertsey Abbey, and afterwards successivE'ly to many royal larged by the present vicar. A cemetery of about half an acre and noble persons, including .Anne of Cleves, Ht>nry, Prince was formed as an addition to the churchyard in 1870 at a cost of Wales, Charles, Duke of York (afU>rwards Charles I.) and of £240, and is now under the control of the vicar. .Alms the Duke of Lauderdale. Douglas House is the property houses for six aged persons of the parish were rebuilt in 1!:!67, and residence of George T. Biddulph esq. By the " Richmond, at the cost of Madame Tildesley De Basset, who at her death Petersham and Ham Open Spaces .Act, 1902," the meadows left a legacy of £300 for the benefit of the female inmates ; they below the Hill, with the manorial rights in the Wood and Peter are now, together with the legacy, absorbed into a general sham common, to!!ether 49 acres, have been vested in the scheme for the administration of all the parochial charities Corporation of Richmond, to be perpetually used tor the of Petersham. -

Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector

Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector Brandon Henderson DISSERTATION.COM Boca Raton Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680): Dutch Classicist, English Portraitist, and Collector Copyright © 2001 Brandon Henderson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Dissertation.com Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2008 ISBN-10: 1-59942-688-9 ISBN-13: 978-1-59942-688-4 Due to large file size, some images within this ebook do not appear in high resolution. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to pay tribute to those who contributed significantly to this work. First, I want to thank my Mom and Dad for their love and encouragement throughout this project and always. Second, I want to thank Dr. Megan Aldrich and Dr. Chantal Brotherton-Ratcliffe at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, for their comments and suggestions. Third, I want to acknowledge the staff at the British Library and the National Art Library within the Victoria and Albert Museum for their support. And finally, I want to thank the library staff at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London, for their assistance. ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ...................................................................................... iv CHAPTER I Introduction -

The Anglers Teddington Lock and Ham House.Pages

A 3.5 mile circular pub walk from The Anglers in Teddington, Middlesex THE ANGLERS, TEDDINGTON LOCK The Anglers is a delightful, family friendly bar, serving up great fare from a peaceful riverside location, making it a AND HAM HOUSE, MIDDLESEX blissful spot for a lingering meal or quick refreshment. The walking route crosses the Thames, before exploring the opposite bank with chance to see famous landmarks including Teddington Lock, Eel Pie Island and Ham House along the way. Easy Terrain Getting there The Anglers is located on Broom Road in Teddington, directly alongside the river by Teddington Lock. You will probably find it easiest to arrive by public transport. 3.5 miles Teddington train station is half a mile up the High Street (from the station go left onto Station Road, then right onto the High Street, go ahead at the lights into Ferry Circular Road and follow this swinging right into Broom Road to find the pub). The area is well connected by bus, there are stops along Ferry Road - you will need the R68, 281 1.5 hours or 285. If you are coming by car, the pub has its own small car park and there is some street parking available (but check local restrictions). 240417 Approximate post code TW11 9NR. Walk Sections Go 1 Start to Teddington Lock Access Notes 1. The route is almost entirely flat, with no gradients to Leave the pub’s front car park onto Broom Road and turn speak of. right along the pavement. Where the road swings left, 2. There are no gates or stiles on route, but you will need turn right towards the river. -

Richmond Upon Thames Est Un Quartier De Londres Richmond Upon Thames È Una Cittadina Di Londra De Todos Los Municipios Londinenses, Richmond Unique

www.visitrichmond.co.uk 2011 - 04 historic gems 2011 - 06 riverside retreat RICHMOND - 2011 08 open spaces 2011 - 10 museums and galleries UPON 2011 - 12 eating out 2011 - 14 shopping 2011 - 16 ghosts and hauntings THAMES 2011 - 18 attractions 2011 - 26 map VisitRichmond Guide 2011 2011 - 28 richmond hill 2011 - 30 restaurants and bars 2011 - 36 accommodation 2011 - 45 events 2011 - 50 travel information French Italian Spanish Richmond upon Thames est un quartier de Londres Richmond upon Thames è una cittadina di Londra De todos los municipios londinenses, Richmond unique. Traversé par la Tamise sur 33 kilomètres unica. Attraversata dal Tamigi che scorre lungo upon Thames es único. Por su centro pasa el río de campagne bordée de maisons élégantes et de 33km di campagna passando di fronte a case Támesis, que fl uye a lo largo de 33 kilómetros beaux jardins. La rivière relie le palais de Hampton eleganti e bellissimi giardini, il fi ume collega il de paisaje, pasando ante viviendas elegantes Court et les jardins botaniques royaux de Kew aux Palazzo di Hampton Court e I Giardini Botanici Reali y hermosos jardines. El río enlaza el palacio de villes de Richmond et de Twickenham. En explorant di KEW alle cittadine di Richmond e Twickenham. Hampton Court y el Real Jardín Botánico de ce lieu de résidence favorite de la royauté, des Esplorando questa località già dimora favorita Kew con las villas de Richmond y Twickenham. grands peintres et des hommes d’Etat, on découvre dalla famiglia reale, da grandi artisti ed uomini Lugar predilecto de la realeza, de hombres de des parcs magnifi ques, des styles d’architecture di stato, potrete scoprire I magnifi ci parchi, gli estado y grandes artistas, cuenta con parques originaux et toute une variété de restaurants et de originali stili architettorici oltre ad un’ ampia varietà magnífi cos y estilos inspirados de arquitectura pubs.