Paintings and Drawings by Francisco Guya in the Collection of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century. Richard Xavier Sanchez Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1975 Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century. Richard Xavier Sanchez Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sanchez, Richard Xavier, "Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century." (1975). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2893. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2893 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and dius cause a blurred image. -

PDF Download

forty-five.com / papers /194 Herbert Marder Reviewed by Guy Tal Mortal Designs I Like the young goat that gives the Caprichos their name, these etchings, unpredictable as goats leaping from boulder to boulder among the hills, evoke the painter Francisco Goya who made them after a sudden illness. At the height of his fame, he falls into a coma, close to death. The doctors have no d i a g n o s i s . H e fi g h t s h i s w a y b a c k a n d c o m e s t o h i m s e l f ,forty- six years old, deaf, ridden by the weight of things. His etchings unveil a prophetic vision, a loneliness like no other, and when they become known years after Goya’s death—timeless. II Court painter to King Carlos IV, Goya is nursed back to health by a wealthy friend. Enemies at court spread rumors…expected not to survive. At least, he’ll never paint again, they say. He ridicules them as soon as he can pick up a brush, paints s m a l l c a n v a s e s , l i k e a j e w e l e r ’ s u n c u t s t o n e s , r e fl e c t i o n s of the nightmare he has lived through, and the inner world his passion unveils, a dark core in which the aboriginal being is close to extinction. -

Goya Dvd Propuesta Unidad Didáctica

UNIT 3. SPAIN IN THE XIX CENTURY 1. The end of the Old Regime 1.1 Carlos IV and the War of Independence 1.2 Galicia during the War of Independence 2. Fernando VII 2.1. Politics 2.2. The Independence of the American colonies 3. Isabel II 4. The Revolutionary Sexennium 5. The Restoration 1 SPAIN IN THE 19th CENTURY (SEEN THROUGH ART) Art can be a great way to understand our history. Every period of our History has been reflected by painters, sculptors, photographers or film- makers. Let´s have a look at Spain in the 19th century with the help of our friends (the artists) TASK 1. BRAINSTORM Let´s check what you remember from unit 1. We can say that the transition from the Old Regime to Liberalism happens in Spain during the 19th century. Try to relate these features with either the Old Regime or the Liberalism Absolute Monarchy Parliament Constitution Equality (same rights for everybody) Different rights and duties for every state No middle classes Sovereignty resides in the nation TASK 2 In pairs, try to arrange this biography of Goya. GOYA´S BIOGRAPHY….TEXT IN PARTS The French occupation in 1808 inspires him two major works (The 2nd of May and The 3rd of May) and the series of engravings “The Disasters Of War” He started painting cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory (in Madrid) during the reign of Charles IV. They were scenes about the customs of the Spanish people like The parasol, The snow or La gallina ciega After a serious illness, Goya became deaf. -

The Dark Romanticism of Francisco De Goya

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya Elizabeth Burns-Dans The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Burns-Dans, E. (2018). The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya (Master of Philosophy (School of Arts and Sciences)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/214 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i DECLARATION I declare that this Research Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which had not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Elizabeth Burns-Dans 25 June 2018 This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the enduring support of those around me. Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Deborah Gare for her continuous, invaluable and guiding support. -

Old Spanish Masters Engraved by Timothy Cole

in o00 eg >^ ^V.^/ y LIBRARY OF THE University of California. Class OLD SPANISH MASTERS • • • • • , •,? • • TIIK COXCEPTION OF THE VIRGIN. I!V MURILLO. PRADO Mi;SEUAI, MADKIU. cu Copyright, 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, and 1907, by THE CENTURY CO. Published October, k^j THE DE VINNE PRESS CONTENTS rjuw A Note on Spanish Painting 3 CHAPTER I Early Native Art and Foreign Influence the period of ferdinand and isabella (1492-15 16) ... 23 I School of Castile 24 II School of Andalusia 28 III School of Valencia 29 CHAPTER II Beginnings of Italian Influence the PERIOD OF CHARLES I (1516-1556) 33 I School of Castile 37 II School of Andalusia 39 III School of Valencia 41 CHAPTER III The Development of Italian Influence I Period of Philip II (l 556-1 598) 45 II Luis Morales 47 III Other Painters of the School of Castile 53 IV Painters of the School of Andalusia 57 V School of Valencia 59 CHAPTER IV Conclusion of Italian Influence I of III 1 Period Philip (1598-162 ) 63 II El Greco (Domenico Theotocopuli) 66 225832 VI CONTENTS CHAPTER V PACE Culmination of Native Art in the Seventeenth Century period of philip iv (162 1-1665) 77 I Lesser Painters of the School of Castile 79 II Velasquez 81 CHAPTER VI The Seventeenth-Century School of Valencia I Introduction 107 II Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto) log CHAPTER VII The Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia I Introduction 117 II Francisco de Zurbaran 120 HI Alonso Cano x. 125 CHAPTER VIII The Great Period of the Seventeenth-Century School of Andalusia (continued) 133 CHAPTER IX Decline of Native Painting ii 1 charles ( 665-1 700) 155 CHAPTER X The Bourbon Dynasty FRANCISCO GOYA l6l INDEX OF ILLUSTRATIONS MuRiLLO, The Conception of the Virgin . -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Francisco Goya, the American Revolution, and the Fight Against the Synarchist Beast-Man by Karel Vereycken

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 13, Number 4, Winter 2004 Francisco Goya, the American Revolution, And the Fight Against The Synarchist Beast-Man by Karel Vereycken s in the case of Rabelais, entering the ly to reassert itself in the aftermath of the British- visual language of Francisco Goya takes orchestrated French Revolution (1789). Aan effort, something that has become Despite this political reversal, Goya continued increasingly difficult for the average Baby in his role as Court Painter to Carlos III’s succes- Boomer. By indicating some of the essential events sors. He was appointed by Carlos IV in 1789, and of Goya’s period and life, I will try to provide you then later, after the Napoleonic invasion of Spain with some of the keys that will enable you to draw in 1808 and the restoration of the Spanish Monar- the geometry of his soul, and to harmonize the chy in 1814, his appointment was reinstated by rhythm of your heart with his. King Ferdinand VII. Francisco Goya y Lucientes was born in 1746, Fighting against despotism while simultaneous- and was 13 years old when Carlos III became ly holding a sensitive post as Painter in the service King of Spain in 1759. Carlos, who was dedicated of the latter two kings—and, what’s more, stricken to the transformation of Spain out of Hapsburg with total deafness at the age of 472—Goya, like all backwardness through Colbertian policies of eco- resistance fighters, was well acquainted with the nomic and scientific development, supported the world of secrecy and deception. -

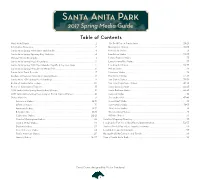

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Twenty-Three Tales

Twenty-Three Tales Author(s): Tolstoy, Leo Nikolayevich (1828-1910) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Famous for his longer novels, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy displays his mastery of the short story in Twenty-Three Tales. This volume is organized by topic into seven different segments. Part I is filled with stories for children, while Part 2 is filled with popular stories for adult. In Part 3, Tolstoy discreetly condemns capitalism in his fairy tale "Ivan the Fool." Part 4 contains several short stories, which were originally published with illustrations to encourage the inexpensive reproduction of pictorial works. Part 5 fea- tures a number of Russian folk tales, which address the themes of greed, societal conflict, prayer, and virtue. Part 6 contains two French short stories, which Tolstoy translated and modified. Finally, Part 7 contains a group of parabolic short stories that Tolstoy dedicated to the Jews of Russia, who were persecuted in the early 1900©s. Entertaining for all ages, Tolstoy©s creative short stories are overflowing with deeper, often spiritual, meaning. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Slavic Russian. White Russian. Ukrainian i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 Part I. Tales for Children: Published about 1872 5 1. God Sees the Truth, but Waits 6 2. A Prisoner in the Caucasus 13 3. The Bear-Hunt 33 Part II: Popular Stories 40 4. What Men Live By (1881) 41 5. A Spark Neglected Burns the House (1885) 57 6. Two Old Men (1885) 68 7. Where Love Is, God Is (1885) 85 Part III: A Fairy Tale 94 8. -

Echoes of the Gothic in Early Twentieth- Century Spanish Music

Echoes of the Gothic in Early Twentieth- Century Spanish Music Jennifer Lillian Hanna ORCID: 0000-0002-2788-9888 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the Master of Music (Musicology/Ethnomusicology) November 2020 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Fine Arts and Music University of Melbourne ii Abstract This thesis explores traces of the Gothic in music and related artforms concerning Spain in the early twentieth century, drawing together a number of case studies with varied proximity to Manuel de Falla and his artistic milieu. A range of Gothic perspectives are applied to a series of musical works, repertories, constructions of race, modes of performance and stage personae, and this examination is preceded by an overview of Gothic elements in their nineteenth-century precursors. The connection between Granada’s Alhambra and the Gothic is based not only on architectural style, but also nocturnal and supernatural themes that can be traced back to the writings of Washington Irving. The idea of Alhambrism and Romantic impressions of the Spanish Gypsy, both of which are associated with the magical, primitive, mystic and nocturnal elements of the Gothic, are also related to constructions of flamenco and cante jondo. The Romantic idea of the Spanish gypsy evolved into primitivism, and attitudes that considered their culture archaic can be placed in a Gothic frame. Flamenco and the notion of duende can also be placed in this frame, and this idea is explored through the poetry and writings of Federico García Lorca and in his interaction with Falla in conceiving the Cante jondo competition of 1922. -

Goya and the War of Independence: a View of Spanish Film Under Franco (1939-1958)

GOYA AND THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE: A VIEW OF SPANISH FILM UNDER FRANCO (1939-1958) Diana Callejas Universidad Autónoma de Madrid At the end of the 1950´s, and with the Franco regimen solidly established in power, Spanish society would commemorate, without excessive display, the 150-year anniversary of the 1808 War of Independence. This conflict had brought the defenders of the monarchy into confrontation against those of liberal constitutionalism, and the conservative tradition against the ideals of progress. For many historians and intellectuals of the era, the war symbolized the authentic redefining landmark of Spain. It was an expression both of a people, who with their minimal military resources were capable of overthrowing the most powerful imperial force of the time, Napoleon, and of the extremely radical opposition to the pressure imposed by foreign ideals. The substantial volume of movies about Goya and the War of Independence in Spanish cinema demands a needed reflection on the importance of this topic. The characteristics found both in the image of Goya, a key figure in Spanish culture who fused in his work the secular and the sacred, and also in the War, a conflict characterized by traditional social change, will be decisive references when this time period on the big screen. They will serve additionally as metaphors in subsequent years. Few studies exist on this topic, and there are fewer still that treat the Franco period; hence, this article offers fundamental insight on how to interpret a period of such change in the Spain’s cultural and ideological history. Understanding this time period is essential to understanding the evolution and development of this view in a year such as 2008, a year which marks the 200-year anniversary of the War of Independence and consequently that of May 2, a date inextricably linked in today’s society with the life and work of Francisco de Goya.