Guns and Protests: Media Coverage of the Conflicts in the Indian State of Chhattisgarh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Kejriwal-Ki-Kahani-Chitron-Ki-Zabani

केजरवाल के कम से परेशां कसी आम आदमी ने उनके ीमखु पर याह फेकं. आम आदमी पाट क सभाओं म# काय$कता$ओं से &यादा 'ेस वाले होते ह). क*मीर +वरोधी और भारत देश को खं.डत करने वाले संगठन2 का साथ इनको श5ु से 6मलता रहा है. Shimrit lee वो म8हला है िजसके ऊपर शक है क वो सी आई ए एज#ट है. इस म8हला ने केजरवाल क एन जी ओ म# कु छ 8दन रह कर भारत के लोकतं> पर शोध कया था. िजंदल ?पु के असल मा6लक एस िजंदल के साथ अAना और केजरवाल. िजंदल ?पु कोयला घोटाले म# शा6मल है. ये है इनके सेकु लCर&म का असल 5प. Dया कभी इAह# साध ू संत2 के साथ भी देखा गया है. मिलमु वोट2 के 6लए ये कु छ भी कर#गे. दंगे के आरो+पय2 तक को गले लगाय#गे. योगेAF यादव पहले कां?ेस के 6लए काम कया करते थे. ये पहले (एन ए सी ) िजसक अIयJ सोKनया गाँधी ह) के 6लए भी काम कया करते थे. भारत के लोकसभा चनावु म# +वदे6शय2 का आम आदमी पाट के Nवारा दखल. ये कोई भी सकते ह). सी आई ए एज#ट भी. केजरवाल मलायमु 6संह के भी बाप ह). उAह# कु छ 6सरफरे 8हAदओंु का वोट पDका है और बाक का 8हसाब मिलमु वोट से चल जायेगा. -

Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009)

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009) New Delhi 151 Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Chairman: Mr. Justice G. N. Ray Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANIZATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPER Shri Vishnu Nagar Editors Guild of India, All India Nai Duniya, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Uttam Chandra Sharma All India Newspaper Editors’ Muzaffarnagar Conference, Editors Guild of India, Bulletin, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Vijay Kumar Chopra All India Newspaper Editors’ Filmi Duniya, Conference, Editors Guild of India, Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Sheetla Singh Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Ms. Suman Gupta Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Saryu Tat Se, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Editors of English Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Yogesh Chandra Halan Editors Guild of India, All India Asian Defence News, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri K. Sreenivas Reddy Indian Journalists Union, Working Visalaandhra, News Cameramen’s Association, Andhra Pradesh Press Association Shri Mihir Gangopadhyay Indian Journalists Union, Press Freelancer, (Ganguly) Association, Working News Bartaman, Cameramen’s Association West Bengal Shri M.K. Ajith Kumar Press Association, Working News Mathrubhumi, Cameramen’s Association, New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Joginder Chawla Working News Cameramen’s Freelancer Association, Press Association, Indian Journalists Union Shri G. -

In Delhi, Actress Ashley Judd Opens up About Being a Victim of Sexual Assault : Celebrity, News - India Today

4/27/2017 In Delhi, actress Ashley Judd opens up about being a victim of sexual assault : Celebrity, News - India Today India World Videos Photos Cricket MoNEWSvies Auto Sports LifTestyleV Tech MEducationAGAZINEBusiness CosmopolitanSearch JOBS IPL 2017 INDIA TODAY MIND ROCKS GUWAHATI MAIL TODAY MOVIES INDIA WORLD PHOTOS VIDEOS CRICKET News Lifestyle Celebrity In Delhi, actress Ashley Judd opens up about being a victim of sexual assault At the World Congress Against Sexual Exploitation of Women and Girls, American actor and activist Ashley Judd spoke about gender discrimination and her personal experiences. Ilma Hasan New Delhi, January 31, 2017 | UPDATED 11:19 IST A + A - Related Stories 5 ways friends and family can help a sexual assault survivor heal How sexual assault affects its survivors and what you can do to help Two hundred and fty key voices in the global movement to abolish prostitution systems gathered for a World Congress Against Sexual Exploitation of Women and Girls in the More From Lifestyle National Capital on Monday, January 30. American actor and activist Ashley Judd, survivor and author Rachel Moran, and Political Suggested Stories leader from Chhattisgarh Soni Sori were present at the event, among others. Actor and activist Ashley Judd spoke against gender discrimination and her own JEE Main Results 2017: Declared at experiences of dealing with sexual assault at the event. The actor, who is India for the next jeemain.nic.in : News few days, opened up about being a victim of assault as a child. JEE Main 2017: -

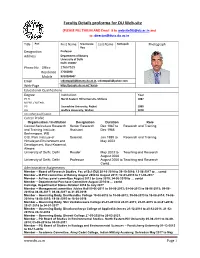

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Prof. First Name Sreenivasa Last Name Kottapalli Photograph Rao Designation Professor Address Department of Botany University of Delhi Delhi 110007 Phone No Office 27667525 Residence 27666898 Mobile 9313294607 Email [email protected], [email protected] Web-Page http://people.du.ac.in/~ksrao Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. North Eastern Hill University, Shillong 1987 M.Phil. / M.Tech. PG Saurashtra University, Rajkot 1980 UG Andhra University, Waltair 1978 Any other qualification Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Central Sericulture Research Senior Research Dec 1987 to Research and Training and Training Institute, Assistant Dec 1988 Berhampore, WB G.B. Pant Institute of Scientist Jan 1989 to Research and Training Himalayan Environment and May 2003 Development, Kosi-Katarmal, Almora University of Delhi, Delhi Reader May 2003 to Teaching and Research August 2008 University of Delhi, Delhi Professor August 2008 to Teaching and Research Contd.. Administrative Assignments Member – Board of Research Studies, Fac of Sci (DU) 30-10-2014 to 29-10-2016; 13-06-2017 to …contd Member – M.Phil committee of Botany August 2008 to August 2011; 12-03-2015 to 11-03-2017 Member – Ad-hoc panel committee August 2012 to June 2015; 24-06-2015 to … contd Member – Departmental Purchase Committee August 2014 to … contd Incharge, Departmental Stores October -

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum.” in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLI 29, July 22, 2006, Pp

Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum.” In Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLI 29, July 22, 2006, pp. 3187-3192 Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum Nandini Sundar1 Visitors to the official Bastar website (www.bastar.nic.in) will ‘discover’ that Gonds “have pro- fertility mentality”, that “marriages...between brothers and sisters are common,” and that “the Murias prefer 'Mahua' drinks rather than medicines for their ailments.” “The tribals of this area”, says the website, “is famous for their 'Ghotuls' where the prospective couples do the 'dating' and have free sex also.” As for the Abhuj Marias, “(t)hese people are not cleanly in their habits, and even when a Maria does bathe he does not wash his solitary garments but leaves it on the bank. When drinking from a stream they do not take up water in their hands but put their mouth down to it like cattle.” Some of the tribals are “leading a savage life”, we are told, “they do not like to come to the outer world and mingle with the modern civilisation.” Into this charming picture of ‘savages’ who ‘shoot down strangers with arrows’, one must unfortunately bring in a few uncomfortable facts. What used to be the former undivided district of Bastar (since 2001 carved into the districts of Dantewada, Bastar and Kanker) is currently a war zone. The main roads, in Dantewada in particular, but also in parts of Bastar and Kanker, are full of CRPF and other security personnel, out on combing operations.2 The Maoists control the jungles. In the frontlines of this battle are ordinary villagers who are being pitted against each other on a scale unparalleled in the history of Indian counterinsurgency. -

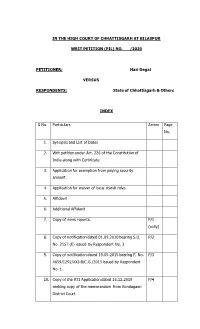

IN the HIGH COURT of CHHATTISGARH at BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS

IN THE HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS: State of Chhattisgarh & Others INDEX S No. Particulars Annex Page No. 1. Synopsis and List of Dates 2. Writ petition under Art. 226 of the Constitution of India along with Certificate. 3. Application for exemption from paying security amount. 4. Application for waiver of locus standi rules. 5. Affidavit 6. Additional Affidavit 7. Copy of news reports. P/1 (colly) 8. Copy of notification dated 01.09.2010 bearing S.O. P/2 No. 2157 (E) issued by Respondent No. 3 9. Copy of notification dated 19.05.2015 bearing F. No. P/3 4659/1292/XXI-B/C.G./2015 issued by Respondent No. 1. 10. Copy of the RTI Application dated 16.12.2019 P/4 seeking copy of the memorandum from Kondagaon District Court. 11. Copy of notification dated 24.11.2015 bearing S. O. P/5 No. 3161 (E) issued by Respondent No. 3 12. The copy of the judgment The State of Chhattisgarh P/6 and Ors. Vs. National Investigative Agency MANU/CG/0884/2019 13. The copy of the relevant pages of The Fifth Report, P/7 Second Administrative Reforms Commission on ‘Public Order — Justice for Each… Peace for All’ dated 01.06.2007. 14. Vakalatnama BILASPUR SHIKHA PANDEY DATED: 10.01.2020 COUNSEL FOR THE PETITIONER IN THE HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS: State of Chhattisgarh & Others SYNOPSIS The present Petition is filed challenging the legality of the notification dated 19.05.2015 F. -

Strange and Dubious Case of Dr.Binayak Singh (By N.T.Ravindranath)

Strange and dubious case of Dr.Binayak Singh (By N.T.Ravindranath) Dr.Binayak Sen, a civil liberty and human rights activist, was arrested by the Chattisgarh police on May 14, 2007 under the provisions of the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005, (CSPSA) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 on the charges of treason, sedition, criminal conspiracy, links with Maoists and acting as a courier for Maoist leader Narayan Sanyal. Earlier on May 6th 2007, the Chattisgarh police had arrested a Kolkota-based businessman Piyush Guha, a tendu leaves trader, from Raipur following recovery of some letters written by jailed Maoist leader Narayan Sanyal from him. Guha‟s confession about the involvement of Binayak Sen in passing on these letters to him had led to Sen‟s arrest. Dr.Binayak Sen, accompanied by his wife Ilina Sen, came to Raipur in the late eighties and worked among the tribals in the area promoting health care activities. He founded an NGO called „Rupander‟ that trained community health workers to work in villages. He was also a noted civil rights activist who maintained close links with the Maoists in the area. Dr.Sen was also in the forefront in launching a campaign against the “Salva Judum”, a people‟s resistance movement against the Maoist activities in the area. Arrest of Binayak Sen in May 2007 had led to wide-spread protest programmes by civil society groups both within India and outside. In December 2007, while Sen was lodged in jail, the Indian Academy of Social Sciences (IASS) declared Binayak Sen as the winner of RR Keithan Gold Medal for "his outstanding contribution to the advancement of science of Nature-Man-Society and his honest and sincere application for the improvement of quality of life of the poor, the downtrodden and the oppressed people of Chhattisgarh”. -

Socio-Economic Survey Report of Villages in Dantewada

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY & NEEDS ASSESSMENT STUDY IN ESSAR STEEL’S PROJECT VILLAGE Baseline Report of the villages located in three blocks of Dantewada in South Bastar Survey Team of Essar Foundation Deepak David Dr. Tej Prakash Pratik Sethe Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1. ESSAR STEEL INDIA LIMITED, VIZAG OPERATIONS - BENEFICIATION PLANT 1.2. ESSAR FOUNDATION 1.3. PROJECT LOCATION 1.4. OBJECTIVE 1.5. METHODOLOGY 1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT CHAPTER 2 AREA PROFILE 2.1. DISTRICT PROFILE 2.2. PROFILE OF THE VILLAGES 2.2.1. Location and Layout 2.2.2. Settlement pattern 2.2.3. Population 2.2.4. Sex Ratio 2.2.5. Literacy 2.2.6. Occupation 2.2.7. Education 2.2.8. Health services 2.2.9. Electrification 2.2.10. Road and transportation 2.2.11. Communication facilities CHAPTER 3 FINDING OF THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY 3.1. BACKGROUND 3.2. METHODOLOGY 3.3. SOCIO- ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE VILLAGES ESSAR FOUNDATION Page 2 of 86 Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh 3.3.1. # of HH members; Average # of members in HH 3.3.2. Caste/ Tribe and sub-group 3.3.3. Age- Sex Distribution 3.3.4. Marital Status 3.3.5. Literacy Rate 3.3.6. Migration 3.3.7. Occupation pattern 3.3.8. Employment and income 3.3.9. Dependency Ratio 3.3.10. Participation in Public Program 3.3.11. Livestock Population 3.3.12. -

Teesta Setalvad

A Mumbai Citizens Legal Rights organisation 2011 Nirant, Juhu Tara Road, Juhu, Mumbai – 400049. Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 26602288 / 26603927 Formation Genesis The Citizens for Justice and Peace, was formed in April 2002 in direct response to the Genocidal carnage against minorities in Gujarat following the tragic burning alive of persons aboard a train at the Godhra railway station. This tragedy was misused deliberately by the government and sections of the administration to allow organised violence in 300 locations spread over 19 of the 25 districts in the state. Within 3 days over 2,500 lives had been lost, property over Rs. 4,000 crores systematically destroyed and over 19,000 homes burnt to cinders. Women and children were specifically targeted as symbols of their community. The victims were the Muslim minority. It was arguably the worst incident of State sponsored Mass Communal Crimes in post-independence India. Formation Individually and collectively, the Trustees of CJP had been involved since the mid-eighties with vocal citizen’s movements against the alarming growth of divisive and hate driven politics of supremacy and exclusion, known on in South Asia as the politics of communalism. Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) has been actively engaged in supporting the struggle for justice for the victim survivors of the communal carnages targeting Gujarat’s Muslims in 2002. In addition, CJP has also emerged as the nodal national group to advise other minority groups, be it Christians, Dalits or women in their legal strategies on how to access justice for violent targeted crimes. -

Media Accreditation Index

LOK SABHA PRESS GALLERY PASSES ISSUED TO ACCREDITED MEDIA PERSONS - 2020 Sl.No. Name Agency / Organisation Name 1. Ashok Singhal Aaj Tak 2. Manjeet Singh Negi Aaj Tak 3. Rajib Chakraborty Aajkaal 4. M Krishna ABN Andhrajyoti TV 5. Ashish Kumar Singh ABP News 6. Pranay Upadhyaya ABP News 7. Prashant ABP News 8. Jagmohan Singh AIR (B) 9. Manohar Singh Rawat AIR (B) 10. Pankaj Pati Pathak AIR (B) 11. Pramod Kumar AIR (B) 12. Puneet Bhardwaj AIR (B) 13. Rashmi Kukreti AIR (B) 14. Anand Kumar AIR (News) 15. Anupam Mishra AIR (News) 16. Diwakar AIR (News) 17. Ira Joshi AIR (News) 18. M Naseem Naqvi AIR (News) 19. Mattu J P Singh AIR (News) 20. Souvagya Kumar Kar AIR (News) 21. Sanjay Rai Aj 22. Ram Narayan Mohapatra Ajikali 23. Andalib Akhter Akhbar-e-Mashriq 24. Hemant Rastogi Amar Ujala 25. Himanshu Kumar Mishra Amar Ujala 26. Vinod Agnihotri Amar Ujala 27. Dinesh Sharma Amrit Prabhat 28. Agni Roy Ananda Bazar Patrika 29. Diganta Bandopadhyay Ananda Bazar Patrika 30. Anamitra Sengupta Ananda Bazar Patrika 31. Naveen Kapoor ANI 32. Sanjiv Prakash ANI 33. Surinder Kapoor ANI 34. Animesh Singh Asian Age 35. Prasanth P R Asianet News 36. Asish Gupta Asomiya Pratidin 37. Kalyan Barooah Assam Tribune 38. Murshid Karim Bandematram 39. Samriddha Dutta Bartaman 40. Sandip Swarnakar Bartaman 41. K R Srivats Business Line 42. Shishir Sinha Business Line 43. Vijay Kumar Cartographic News Service 44. Shahid K Abbas Cogencis 45. Upma Dagga Parth Daily Ajit 46. Jagjit Singh Dardi Daily Charhdikala 47. B S Luthra Daily Educator 48.