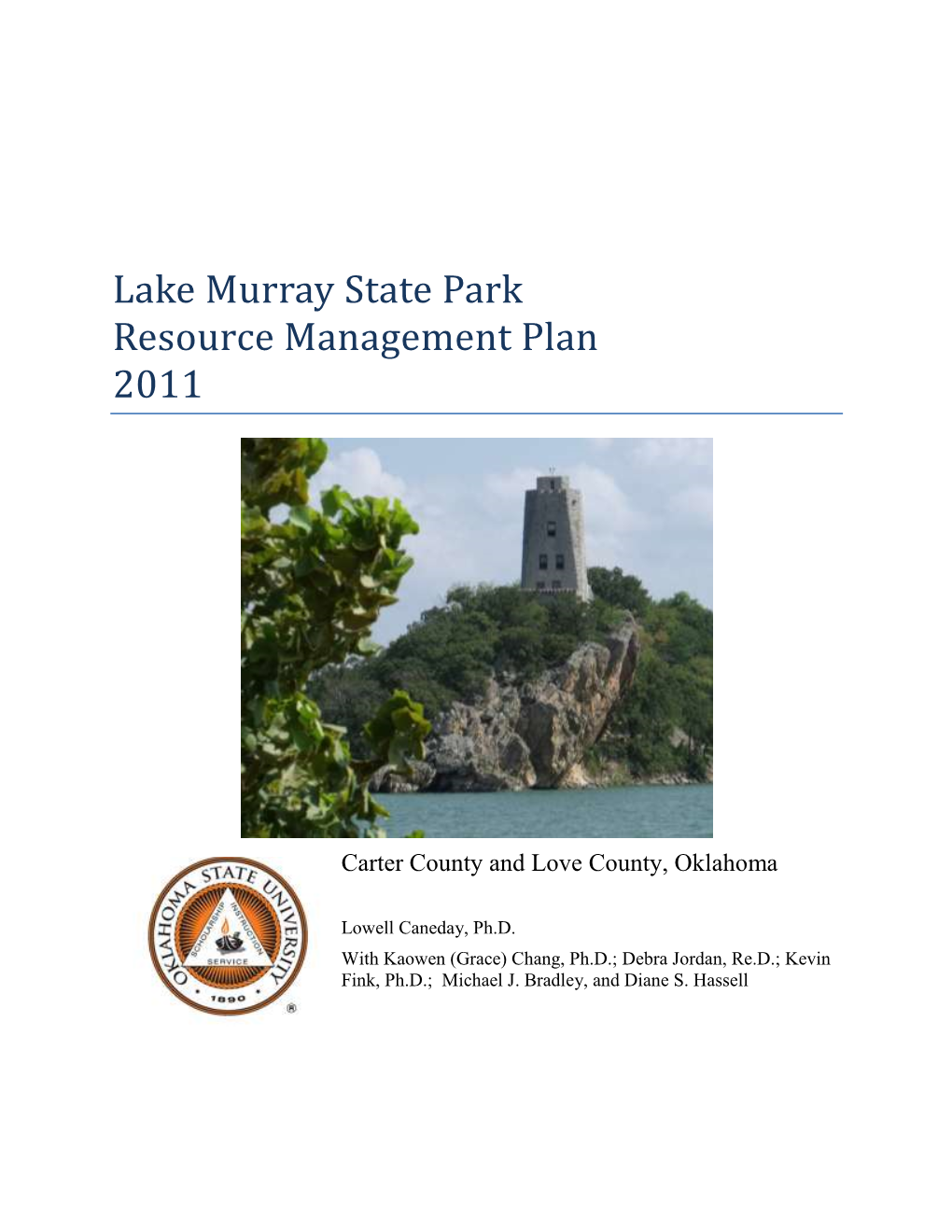

Lake Murray State Park Resource Management Plan 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works Progress Administration Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Projects Collection Compiled 1969 - Revised 2002 Works Progress Administration (WPA) Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Project Collection. Records, 1937–1941. 23 feet. Federal project. Book-length manuscripts, research and project reports (1937–1941) and administrative records (1937–1941) generated by the WPA Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ projects for Oklahoma during the 1930s. Arranged by county and by subject, these project files reflect the WPA research and findings regarding birthplaces and homes of prominent Oklahomans, cemeteries and burial sites, churches, missions and schools, cities, towns, and post offices, ghost towns, roads and trails, stagecoaches and stage lines, and Indians of North America in Oklahoma, including agencies and reservations, treaties, tribal government centers, councils and meetings, chiefs and leaders, judicial centers, jails and prisons, stomp grounds, ceremonial rites and dances, and settlements and villages. Also included are reports regarding geographical features and regions of Oklahoma, arranged by name, including caverns, mountains, rivers, springs and prairies, ranches, ruins and antiquities, bridges, crossings and ferries, battlefields, soil and mineral conservation, state parks, and land runs. In addition, there are reports regarding biographies of prominent Oklahomans, business enterprises and industries, judicial centers, Masonic (freemason) orders, banks and banking, trading posts and stores, military posts and camps, and transcripts of interviews conducted with oil field workers regarding the petroleum industry in Oklahoma. ____________________ Oklahoma Box 1 County sites – copy of historical sites in the counties Adair through Cherokee Folder 1. Adair 2. Alfalfa 3. Atoka 4. Beaver 5. Beckham 6. -

Clayton Lake State Park Resource Management Plan Pushmataha County, Oklahoma

Clayton Lake State Park Resource Management Plan Pushmataha County, Oklahoma Lowell Caneday, Ph.D. 6/30/2015 Hung Ling (Stella) Liu, Ph.D. I-Chun (Nicky) Wu, Ph.D. Updated: December 2018 This page intentionally left blank. i Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the assistance of numerous individuals in the preparation of this Resource Management Plan. On behalf of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department’s Division of State Parks, staff members were extremely helpful in providing access to information and in sharing of their time. The essential staff providing assistance for the development of the RMP included Gary Daniel, manager of Clayton Lake State Park, and Johnny Moffitt, Associate Director of Little Dixie Action Agency, Inc. In addition, John Parnell, manager of Raymond Gary State Park, and Ron Reese, manager of Hugo Lake State Park, attended the initial meetings for Clayton Lake State Park and provided insight into management issues. Assistance was also provided by Kris Marek, Doug Hawthorne, Don Shafer and Ron McWhirter – all from the Oklahoma City office of the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. Merle Cox, Regional Manager of the Southeastern Region of Oklahoma State Parks also attended these meetings and assisted throughout the project. It is the purpose of the Resource Management Plan to be a living document to assist with decisions related to the resources within the park and the management of those resources. The authors’ desire is to assist decision-makers in providing high quality outdoor recreation experiences and resources for current visitors, while protecting the experiences and the resources for future generations. Lowell Caneday, Ph.D., Regents Professor Leisure Studies Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 74078 ii Abbreviations and Acronyms ADAAG ................................................ -

Accessible Information Alabaster Caverns State Park

Accessible Information Alabaster Caverns State Park The following park amenities are available: Park office entrance and main parking lot The Visitor Center Picnic shelter #1 One RV site Comfort station Playground Cavern tours are not recommended for the following persons with: Mobility problems Respiratory difficulties Night blindness Claustrophobia Bending or stooping difficulties Updated 10/2013-kc Accessible Information Arrowhead State Park The following park amenities are available: Lakeview Circle Campground: One accessible restroom and parking area Hitching Post Campground: One accessible restroom and parking area Turkey Flats Campground: Four accessible RV sites One accessible restroom Group Camp: Two bunkhouses Two comfort stations Community Building with bedroom and parking Echo Ridge Campground Site #429 and one comfort station Park office entrance and parking 2013-kc Accessible Information Beavers Bend State Park The following park amenities are available: Fully accessible comfort station near the old Nature Center Acorn Campground: One fully accessible comfort station, five RV sites Armadillo campground on Stevens Gap: One comfort station, three RV sites Carson Creek: One fully accessible comfort station, one RV site Blue Jay primitive campground: Two sites Coyote primitive campground: Two sites Cabin #48 accessible and meets ADA specs. Lakeview Lodge-One double/double room, one king and one suite, and all public areas of the lodge (Stevens Gap Area.) Other: Forest Heritage Center entrance and public restrooms 2013-kc Accessible -

Surface Ownership and BIA-Administered Tribal

Richardson Lovewell Washington State County Surface Ownership and BIA- Wildlife Lovewell Fishing Lake And Falls City Reservoir Wildlife Area St. Francis Keith Area Brown State Wildlife Sebelius Lake Norton Phillips Brown State Fishing Lake And Area Cheyenne (Norton Lake) Wildlife Area Smith County Washington Marshall Wildlife Area County Lovewell Nemaha Fishing Lake County State ¤£77 County Wildlife administered Tribal and Allotted 36 Rawlins State Park Fishing Lake Sabetha ¤£ Decatur Norton Area County Republic County Norton County Marysville ¤£75 36 36 Brown County ¤£ £36 County ¤£ Washington Phillipsburg ¤ Jewell County Nemaha County Doniphan County St. Subsurface Minerals Estate £283 County Joseph ¤ Atchison State Kirwin National Glen Elder Jamestown Tuttle Fishing Lake Wildlife Refuge Reservoir Sherman (Waconda Lake) Wildlife Area Creek Atchison State Fishing Webster Lake 83 State Glen Elder Lake And Wildlife Area County ¤£ Sheridan Nicodemus Tuttle Pottawatomie State Thomas County Park Webster Lake Wildlife Area Concordia State National Creek State Fishing Lake No. Atchison Parks 159 BIA-managed tribal and allotted subsurface Fishing Lake Historic Site Rooks County 1 And Wildlife ¤£ Fort Colby Cloud County Atchison Leavenworth Goodland 24 Beloit Clay County Holton 70 ¤£ Sheridan Osborne Riley County §¨¦ 24 County Glen Elder ¤£ Jackson 73 County Graham County Rooks State County ¤£ minerals estate State Park Mitchell Clay Center Pottawatomie County Sherman State Fishing Lake And ¤£59 Leavenworth Wildlife Area County County Fishing -

2005 Oklahoma State Highway

Avard ...........H-1.....26 Big Cedar........P-6 Bradley..........J-5.....826 Byng............L-5...1,090 Cavanal .........P-5 Clearview........M-4.....56 Corn............H-4....591 Davidson ........H-7....375 Dundee .........K-7 Eubanks.........N-6 Forty One........ H-5 Gideon ..........O-3 Haileyville........N-5....891 Hickory..........L-6.....87 Humphreys ......H-6 Kemp ...........M-8....144 Lane............M-7 Logan...........F-2 Manchester ......J-1.....104 Middleberg.......J-5 Mustang .........J-4..13,156 Numa ...........J-1 Oscar ...........J-7 Petersburg.......K-8 Pyramid Corners . O-1 Ringold..........O-7 Savanna.........N-5....730 Smithville ........P-6 Stratford . .....L-6...1,474 Temple. ...I-7...1,146 Ulan . ......N-5 Warner..........O-4...1,430 WhiteOak.......O-1 PLACE NAMES Avery ...........L-3 Bigheart .........M-1 Braggs ..........O-4....301 Byron ...........I-1......45 Cedar Springs ....I-3 Clemscott........K-7 Cornish .........K-7....172 Davis ...........K-6...2,610 Durant ..........M-7.13,549 Eufaula .........N-4...2,639 Foss............H-4....127 Glencoe .........L-3....583 Hallett...........L-2....168 Higgins..........N-5 Hunter ..........J-2.....173 Kendrick.........L-3....138 Langley .........O-2....669 Lone Grove ......K-7...4,631 Mangum ........G-6...2,924 Midway..........K-4 Mutual ..........H-3.....76 Oakland .........L-7....674 Ottawa..........O-1 Pharaoh .........M-4 Quapaw .........O-1....984 Ringwood........I-2.....424 Sawyer..........O-7 Snow . .........N-6 Stringtown . .....M-6....396 Terlton..........L-3.....85 -

Title 800. Department of Wildlife Conservation Chapter 10. Sport Fishing Rules

TITLE 800. DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE CONSERVATION CHAPTER 10. SPORT FISHING RULES SUBCHAPTER 1. HARVEST AND POSSESSION LIMITS 800:10-1-4. Size limits on fish There are no length and/or size limit restrictions on any game or nongame fish taken from waters of this state, except as follows: (1) All largemouth and smallmouth bass less than fourteen (14) inches in total length must be returned to the water unharmed immediately after being taken from public waters unless regulated by specific municipal ordinance or specified in regulations listed below: Lakes and Reservoirs with no length limit on largemouth and smallmouth bass - Lake Murray, all waters in the Wichita National Wildlife Refuge. (2) All largemouth and smallmouth bass between thirteen (13) and sixteen (16) inches in total length must be returned unharmed immediately after being taken from lakes Chimney Rock (W.R. Holway), Arbuckle, Okmulgee and Tenkiller Lake (downstream from Horseshoe Bend boat ramp). (3) All crappie (Pomoxis sp.) less than 10 inches in total length must be returned to the water unharmed immediately after being taken from Lakes Arbuckle, Tenkiller, Hudson, Texoma, Ft. Gibson, including all tributaries and upstream to Markham Ferry Dam and Grand Lake, including all tributaries to state line. (4) All walleye, sauger, and saugeye (sauger x walleye hybrid) less than 14 inches in total length must be returned to the water unharmed immediately after being taken statewide, except at Great Salt Plains Reservoir and tailwater where the size limit does not apply, the Arkansas River from Keystone Dam downstream to the Oklahoma state line including all major tributaries upstream to impoundment and R.S. -

Congressional Record—Senate S5228

S5228 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE July 31, 2019 Oklahoma City area and all around You can’t go through Oklahoma Mr. HAWLEY. Mr. President, I op- Tulsa, to spend as much time as I can without stopping at Cattlemen’s pose the confirmation of U.S. District with as many different people as I can Steakhouse and enjoying a great steak Court nominee Karin Immergut. She to find out what is going on in Okla- or without driving out west to see the went through the committee confirma- homa. I get this one precious month a Stafford Air & Space Museum. People tion process in 2018, before I joined the year to make sure I have focus time in who travel to Washington, DC, go to Senate Judiciary Committee, and sub- the State to see as many people as I the Air and Space Museum, and I will sequently, she was part of a package of can. often smile at them and say: Do not judges who were renominated and I got to thinking about this and the miss the Air & Space Museum that is voted out earlier this year. I later privilege that I have really had in in Weatherford, OK, because the Staf- learned that the nominee had issued a being able to travel around my State ford Air & Space Museum has a re- questionable abortion opinion and is and see so many people and so many markable collection from a fantastic pro-choice. places, to get on Route 66, travel the Oklahoma astronaut. f State from east to west, and see ex- The Great Salt Plains in Jet and the EXECUTIVE CALENDAR actly what is going on. -

Oklahoma's Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. UNOFFICIAL TITLE 785. OKLAHOMA WATER RESOURCES BOARD CHAPTER 45. OKLAHOMA'S WATER QUALITY STANDARDS Introduction: This document contains the Oklahoma Water Quality Standards promulgated by the Oklahoma Water Resources Board including all amendments which are effective as of September 13, 2020. This document was prepared by Oklahoma Water Resources Board staff as a convenience to the reader, and is not a copy of the official Title 785 of the Oklahoma Administrative Code. The rules in the official Oklahoma Administrative Code control if there are any discrepancies between the Code and this document. Subchapter Section 1. General Provisions ........................................................................................... 785:45-1-1 3. Antidegradation Requirements ......................................................................... 785:45-3-1 5. Surface Water Quality Standards ..................................................................... 785:45-5-1 7. Groundwater Quality Standards........................................................................ 785:45-7-1 Appendix A. Designated Beneficial Uses for Surface Waters Appendix B. Areas With Waters of Recreational and/or Ecological Significance Appendix C. Suitability of Water for Livestock and Irrigation Uses [REVOKED] Appendix D. Classifications for Groundwater in Oklahoma Appendix E. Requirements for Development of Site Specific Criteria for Certain Parameters Appendix F. Statistical Values of the Historical Data for Mineral Constituents of Water Quality (beginning October 1976 ending September 1983, except as indicated) Appendix G. -

Geology Project Book 1: Beginner

4H•ENV•101 Geology Project Book 1: Beginner Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service Division of Agriculture Sciences and Natural Resources Oklahoma State University Oklahoma Energy Resources Board Geology Project Book 1—Beginner Oklahoma is a state that is geologically diverse and interesting. From the lava-covered mesas at the western tip of the panhandle to the Ouachita Mountains in southeastern corner of the state, the various landscapes make our state a unique place to live. The flatness or hilliness of our own backyard, neighborhood park or family farm are all related to geology. Geology plays a major role in many important aspects of our lives. From the fuels we use for transportation, farming, industry or heat, to the water we need for drinking and irrigation or the soils that sustain our agricultural industry, geologic resources are critical to our existence. The geology of Oklahoma is important to our economy. Oklahoma is a leading producer of natural gas and oil. Thousands of Oklahomans rely on the petroleum business for their livelihood. All citizens of our state benefit indirectly by the contributions that oil and natural gas companies and their employees make to education and the arts. The soils that provide the foundation of Oklahoma’s rich agriculture industry are related to the underlying bedrock. Our scenic resources are the result of the interaction of climate and geology over time. The rich rock resources of Oklahoma are mined or quarried to make building stone, cement, monuments and construction material. The purpose of the 4-H geology project is to increase our understanding of the natural world in which we live. -

Leave Today and Stay and Play at One of Oklahoma's Premier Parks And

Green leaf State Park Lake Murray State Park La ke Texoma State Park Lake Murray State Park Beavers Bend Stat e Park Robbers Cave State Park Oklahoma State Parks 1. Adair State Park - Stilwell, OK 2. Alabaster Caverns State Park - Freedom, OK 3. Arrowhead State Park - Canadian, OK 4. Beaver Dunes State Park - Beaver, OK (} Blackwell 5. Beavers Bend Resort Park - Broken Bow, OK 6. Bernice State Park - Grove, OK 7. Black Mesa Stat e Park - Kenton, OK 8. Boggy Depot State Park - Atoka, OK 9. Boi ling Springs State Park - Woodward, OK 10. Cherokee State Park - Disney, OK 11. Cherokee La nding State Park - Park Hill, OK National Park Service Areas 12. Clayton Lake State Park - Clayton, OK NHS National Historic Site 13. Crowder Lake State Park - Weatherford, OK Roman Nose State Park NRA National Recreation Area 14. Disney/Little Bl ue State Parks - Disn ey, OK NMem National Memorial Oklahoma 15. Fort Cobb State Park - Fort Cobb, OK Crty - 16. Foss State Park - Foss, OK Oklahoma State Parks 17. Lake Eufaula State Park - Checotah, OK Locations on map are approximate 18. Great Plai ns State Park - Mount ain Park, OK 19. Great Salt Plains State Park - Jet, OK 20. Greenleaf State Park - Braggs, OK --- National Historic Trails 21. Heavener Ru nestone State Park - Heavener, OK 22. Honey Creek State Park - Grove, OK Erick Historic Route 23. Hugo Lake State Park - Hugo, OK 24. Keystone State Park - Mannford, OK 25. La ke Eu cha State Park - Jay, OK Oklahoma Tourism 26. Lake Murray Resort Park - Ardmore, OK 0 Information Centers 27. -

Oklahoma Equestrian Trail Riders Association, Inc

Oklahoma Equestrian Trail Riders Association, Inc. This Information is provided by the Oklahoma Equestrian Trail Riders Association, Inc. OETRA is not liable for any information here, it is just provided as a service. www.oetra.com Oklahoma State Parks A. Arrowhead State Park (918)339-2204 http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.293 Adjacent to Lake Eufaula, equestrian camp with RV sites, electric, water, dump station, primitive camping, pavilion. B. Foss Lake State Park (580) 592-4433 http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.2848 Clinton, OK. Warrior Trail (multi-use) equestrian campground, electricity, RV sites, water, comfort station, picket posts and pavilion. No horse rentals available. C. Great Salt Plains State Park (580) 626-4731 http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.3204 Hwy 38 N. of Jet OK. George Sibley Trail (multi-use) Campground, electricity, RV sites, picket posts, water, comfort station, pavilion. No horse rentals are available. D. Lake Murray State Park, Ardmore (580) 223-4044 Park Office http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.4358 They have a barn to stable the horses. There are electric and water hook-ups. Bathrooms with showers and really nice trails. The only thing is the trails are not well marked. Also it is located in the field trial area. You need to call in advance to make sure they are not having field trial runs. Rental horses are available March- November - 580-223-8172 E. McGee Creek State Park (580) 889-5822 http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.4972 N.E. of Atoka and N. -

Oklahoma Rocks State Parks Workbook

Tenkiller Red Rock Canyon Roman Nose Alabaster Caverns Black Mesa Newspapers for this educational program provided by: Beavers Bend Lake Murray Introduction and Geologic Setting: Oklahoma is blessed with a wonderful geological heritage that benefits us in many ways. In addition to our petroleum, coal, and mineral resources, the state has a variety of exposed rocks that can be quarried for many uses, all of which are a huge boon to our economy. Oklahoma’s geology is internationally known because of these economic resources, and also because of the size and diversity of the many geologic features that are exposed and available for viewing around the state and in our 35 state parks. In the southern part of the state, many of these parks feature mountains that were formed and shaped by a variety of dynamic geologic processes. Other Oklahoma parks contain different kinds of geological wonders that include: the world’s largest natural gypsum cave that is open to the public at Alabaster Caverns State Park; an extinct volcano at Black Mesa State Park; and the rugged canyons of Roman Nose State Park. Table of Contents The Oklahoma Geological Survey brings this issue of Oklahoma Rocks! – State Parks to Introduction ....................................... 2 you so that you can better understand and enjoy our geological wonders! They are readily Geologic Setting .............................. 3-5 Tenkiller ........................................ 6, 7 available at locations near you. Roman Nose/Alabaster Caverns ........ 8, 9 CREDITS: The content for this program was developed by the Red Rock Canyon ....................... 10, 11 Oklahoma Geological Survey. Special acknowledgments go to Dr. G. Black Mesa ................................