UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Graciela Paraskevaídis: Homenaje a Silvestre Revueltas 1 -.::GP-Magma

Graciela Paraskevaídis: Homenaje a Silvestre Revueltas 1 Planos Silvestre Revueltas - pocas veces el nombre y apellido de un artista han sido tan premonitorios como en este caso - es sin duda alguna uno de los creadores más asombrosos y originales del siglo XX. Su México no es sólo el de los mariachis, sones y corridos, sino también el de las calaveras y esqueletos de José Guadalupe Posada, los murales de Diego Rivera, las pinturas de Frida Kahlo, los poetas estridentistas y los trasterrados europeos como Lev Trotski, Tina Modotti, Hanns Eisler, Rodolfo Halffter y Otto Mayer Serra. El momento político de su máxima explosión creativa coincide con el sexenio del gobierno progresista del general Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940), impulsor de cambios sociales (la reforma agraria) y culturales (la reforma educativa y el apoyo al cine). Por otro lado, abarca la guerra civil española (que contó a Revueltas como defensor de la República) y el inicio de la segunda guerra mundial. También es el México de su colaboración musical y amistad personal primero y, a partir de 1935, del rompimiento definitivo y la dura confrontación con su coetáneo Carlos Chávez (1899-1978). Tema éste bastante tabú aún hoy en México, la perspectiva histórica ha ido echando luz sobre un enfrentamiento signado sin duda por irreconciliables visiones del mundo. Chávez y Revueltas representaban posicionamientos antagónicos: el pionero Revueltas frente al académico Chávez; el luchador idealista frente al pragmático calculador; el creador apasionado frente al detentador del poder musical en México; el comprometido testigo sonoro de su tiempo y época frente al “músico de hierro” como lo llamara Revueltas 2, primero modernista y luego cultor de un nacionalismo indigenista con tintes neoclásicos europeos, opciones estéticas éstas comparables a algunas del brasileño Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959). -

Activity Sheet

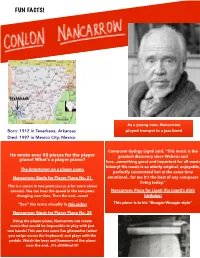

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

Federico Ibarra - a Case Study

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-29-2019 11:00 AM Contexts for Musical Modernism in Post-1945 Mexico: Federico Ibarra - A Case Study Francisco Eduardo Barradas Galván The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Ansari, Emily. The University of Western Ontario Co-Supervisor Wiebe, Thomas. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Francisco Eduardo Barradas Galván 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Barradas Galván, Francisco Eduardo, "Contexts for Musical Modernism in Post-1945 Mexico: Federico Ibarra - A Case Study" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6131. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6131 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the musical modernist era in Mexico between 1945 and the 1970s. It aims to provide a new understanding of the eclecticism achieved by Mexican composers during this era, using three different focal points. First, I examine the cultural and musical context of this period of Mexican music history. I scrutinize the major events, personalities, and projects that precipitated Mexican composers’ move away from government-promoted musical nationalism during this period toward an embrace of international trends. I then provide a case study through which to better understand this era, examining the early life, education, and formative influences of Mexican composer Federico Ibarra (b.1946), focusing particularly on the 1960s and 1970s. -

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. As performed in principal recordings (or demos) by or with Gram Parsons or, in the case of Gram Parsons compositions, performed by others. Gram often varied, adapted or altered the lyrics to non-Parsons compositions; those listed here are as sung by him. Gram’s birth name was Ingram Cecil Connor III. However, ‘Gram Parsons’ is used throughout this document. Following his father’s suicide, Gram’s mother Avis subsequently married Robert Parsons, whose surname Gram adopted. Born Ingram Cecil Connor III, 5th November 1946 - 19th September 1973 and credited as being the founder of modern ‘country-rock’, Gram Parsons was hugely influenced by The Everly Brothers and included a number of their songs in his live and recorded repertoire – most famously ‘Love Hurts’, a truly wonderful rendition with a young Emmylou Harris. He also recorded ‘Brand New Heartache’ and ‘Sleepless Nights’ – also the title of a posthumous album – and very early, in 1967, ‘When Will I Be Loved’. Many would attest that ‘country-rock’ kicked off with The Everly Brothers, and in the late sixties the album Roots was a key and acknowledged influence, but that is not to deny Parsons huge role in developing it. Gram Parsons is best known for his work within the country genre but he also mixed blues, folk, and rock to create what he called “Cosmic American Music”. While he was alive, Gram Parsons was a cult figure that never sold many records but influenced countless fellow musicians, from the Rolling Stones to The Byrds. -

Download Booklet

Credits works by Executive producer: Jonathan Golove. Nicandro Tamez Recording producer: Omar Tamez. Leandro Espinosa Session producers: Karl Toews (Tracks 1, 3-4, 6-8) and Omar Tamez (2,5). Mario Lavista Omar Tamez Audio engineer and editing: Chris Jacobs. Manuel de Elías Location: Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Liner notes: Jonathan Golove, except where noted. Stephen Manes, piano Cover painting: Ubudo by Teresita Soto, based on Nicandro Tamez’s score of the same title. Emilio Tamez, percussion Publishers Nicandro Tamez’s Introduccíon al Duo I and Monomaquia I are available from Omar Tamez. Leandro Espinosa’s Duo “De la Obscuridad a la Luz” is available from the composer. Mario Lavista’s Cuaderno de viaje and Quotations are published by Ediciones Mexicana de Musica, A.C. Omar Tamez’s Las Voces Internas is available from the composer. Manuel de Elías’ Homérica is available from the composer. Acknowledgements This recording was made possible by the support of the University of Buffalo and the UB Department of Music. I wish to thank members of the University of Buffalo staff, Phil Rehard, concert manager, and Gary Shipe, piano technician, and UB faculty percussionist Tom Kolor, for their gracious assistance with this project. Thanks also to David Felder and the Robert and Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music and Margarita Vargas and the UB Gender Institute for additional support, as well as to Ana R. Alonso-Minutti for her program notes and translation assistance. WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1235 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

Peermusic Classical 250 West 57Th Street, Suite 820 New York, NY 10107 Tel: 212-265-3910 Ext

classical RentalRentalSalesSales CatalogCatalogCatalogCatalog 20092009 Peermusic Classical 250 West 57th Street, Suite 820 New York, NY 10107 tel: 212-265-3910 ext. 17 fax: 212-489-2465 [email protected] www.peermusicClassical.com RENTAL CATALOG REPRESENTATIVES WESTERN HEMISPHERE, JAPAN Subito Music Corp. 60 Depot Rd. Verona, NJ 07044 tel:973-857-3440 fax: 973-857-3442 email: [email protected] www.subitomusic.com CONTINENTAL EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND Peermusic Classical GmbH Faber Music Ltd. Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd. Mühlenkamp 45 3 Queen Square 4 Lentara Court D22303 Hamburg London WC1N 3AU Cheltenham Victoria 3192 Germany England Australia tel: 40 278-37918 tel: 0171 278-7436 tel: 61 3 9585 3300 fax: 40 278-37940 fax: 0171 278-3817 fax: 61 3 9585 8729 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] email: [email protected] www.peermusic-classical.de www.fabermusic.com www.halleonard.com.au Please place rental orders directly with our representatives for the territories listed above. Contact Peermusic Classical New York for all other territories. Scores indicated as being published for sale may be ordered from: Hal Leonard Corp., 7777 West Bluemound Rd., PO Box 13819, Milwaukee, WI 53213 tel: (414) 774-3630 fax: (414) 774-3259 email: [email protected] www.halleonard.com Perusal scores: [email protected] Peermusic Classical, a division of Peermusic, publishes under four company names: Peer International Corp., Peermusic III, Ltd. (BMI), Southern Music Publishing Co., Inc., and Songs of Peer, Ltd. (ASCAP) Peer International Corporation is sole world representative for music publications of PAN AMERICAN UNION and EDICIONES MEXICANAS DE MUSICA, A.C.