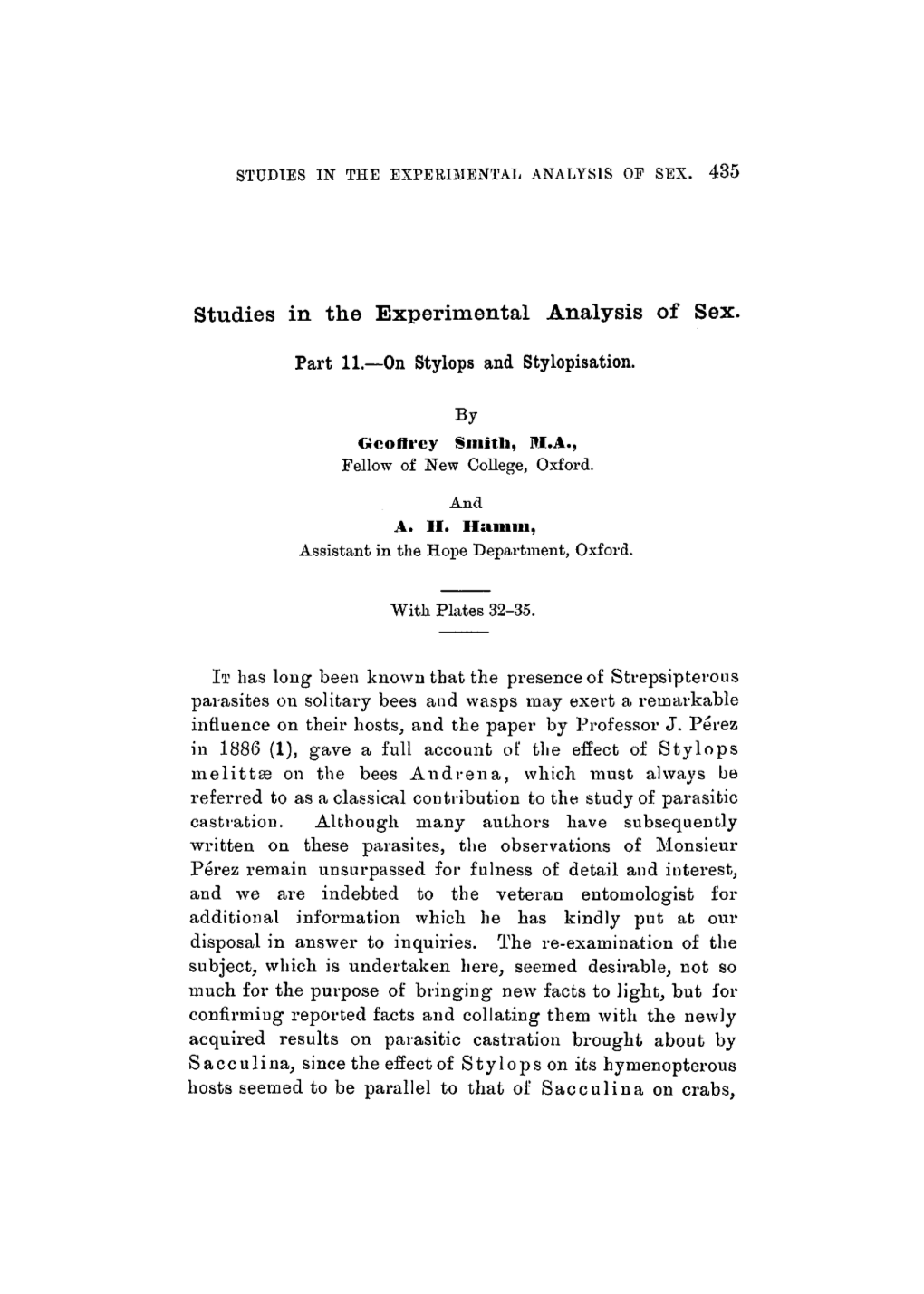

On Stylops and Stylopisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coleoptera: Introduction and Key to Families

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2012 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Vol. IV. Part 1. HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS COLEOPTERA INTRODUCTION AND KEYS TO FAMILIES By R. A. CROWSON LONDON Published by the Society and Sold at its Rooms 41, Queen's Gate, S.W. 7 31st December, 1956 Price-res. c~ . HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS The aim of this series of publications is to provide illustrated keys to the whole of the British Insects (in so far as this is possible), in ten volumes, as follows : I. Part 1. General Introduction. Part 9. Ephemeroptera. , 2. Thysanura. 10. Odonata. , 3. Protura. , 11. Thysanoptera. 4. Collembola. , 12. Neuroptera. , 5. Dermaptera and , 13. Mecoptera. Orthoptera. , 14. Trichoptera. , 6. Plecoptera. , 15. Strepsiptera. , 7. Psocoptera. , 16. Siphonaptera. , 8. Anoplura. 11. Hemiptera. Ill. Lepidoptera. IV. and V. Coleoptera. VI. Hymenoptera : Symphyta and Aculeata. VII. Hymenoptera: Ichneumonoidea. VIII. Hymenoptera : Cynipoidea, Chalcidoidea, and Serphoidea. IX. Diptera: Nematocera and Brachycera. X. Diptera: Cyclorrhapha. Volumes 11 to X will be divided into parts of convenient size, but it is not possible to specify in advance the taxonomic content of each part. Conciseness and cheapness are main objectives in this new series, and each part will be the work of a specialist, or of a group of specialists. -

Strepsiptera: Stylopidae), a New Record for Canada

Zootaxa 4731 (2): 287–291 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4731.2.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:15FBE21E-8CF0-4E67-8702-FD2E225C0DE9 Description of the Adult Male of Stylops nubeculae Pierce (Strepsiptera: Stylopidae), a New Record for Canada ZACHARY S. BALZER1 & ARTHUR R. DAVIS1,2 1Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, 112 Science Place, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2Corresponding author Abstract The morphology of the adult male of Stylops nubeculae Pierce, encountered in stylopized gasters of two adult bees of Andrena peckhami, is described for the first time. This species was previously known only from the endoparasitic adult female found in Colorado, USA. We report a new locality for this species in Alberta, Canada. Key words: Andrena peckhami, morphology, Stylopinae, Canada Introduction Straka (2019) has reported 27 species of Strepsiptera from Canada, 15 of which belong to the family Stylopidae, al- though the newly added Canadian strepsipteran species have yet to be disclosed. The Stylopidae parasitize four bee families (Andrenidae, Colletidae, Halictidae, and Melittidae; Kathirithamby 2018), and this family of twisted-wing parasites consists of nine genera: Crawfordia Pierce, 1908; Eurystylops Bohart, 1943; Halictoxenos Pierce, 1909; Hylecthrus Saunders, 1850; Jantarostylops Kulicka, 2001; Kinzelbachus Özdikmen, 2009; Melittostylops Kinzel- bach, 1971; Rozeia Straka, Jůzova & Batelka, 2014; and Stylops Kirby, 1802 (Kathirithamby 2018). The latter is the largest genus, with 117 species described (Kathirithamby 2018). -

By Stylops (Strepsiptera, Stylopidae) and Revised Taxonomic Status of the Parasite

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 519:Rediscovered 117–139 (2015) parasitism of Andrena savignyi Spinola (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae)... 117 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.519.6035 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Rediscovered parasitism of Andrena savignyi Spinola (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae) by Stylops (Strepsiptera, Stylopidae) and revised taxonomic status of the parasite Jakub Straka1, Abdulaziz S. Alqarni2, Katerina Jůzová1, Mohammed A. Hannan2,3, Ismael A. Hinojosa-Díaz4, Michael S. Engel5 1 Department of Zoology, Charles University in Prague, Viničná 7, CZ-128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic 2 Department of Plant Protection, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, PO Box 2460, Riyadh 11451, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 3 Current address: 6-125 Cole Road, Guelph, Ontario N1G 4S8, Canada 4 Departamento de Zoología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, DF, Mexico 5 Division of Invertebrate Zoology (Entomology), American Museum of Natural Hi- story; Division of Entomology, Natural History Museum, and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 1501 Crestline Drive – Suite 140, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-4415, USA Corresponding authors: Jakub Straka ([email protected]); Abdulaziz S. Alqarni ([email protected]) Academic editor: Michael Ohl | Received 29 April 2015 | Accepted 26 August 2015 | Published 1 September 2015 http://zoobank.org/BEEAEE19-7C7A-47D2-8773-C887B230C5DE Citation: Straka J, -

Strepsiptera: Stylopidae)

Zootaxa 4674 (4): 496–500 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4674.4.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4043E258-29DC-4F3B-963E-C45D421BB7B4 Description of the Adult Male of Stylops advarians Pierce (Strepsiptera: Stylopidae) ZACHARY S. BALZER1 & ARTHUR R. DAVIS1,2 1Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, 112 Science Place, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2Corresponding author. Department of Biology, CSRB Rm 320.6, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, S7N 5E2. E-mail: [email protected] The morphology of the adult male of Stylops advarians Pierce is described for the first time. This species was previously known only from the endoparasitic adult female and the host-seeking, first-instar larva. Members of Stylops are cosmo- politan, and Stylops advarians can be found parasitizing Andrena milwaukeensis Graenicher in western Canada. Key words: Andrena milwaukeensis, morphology, Stylopinae, Canada Fifteen of Canada’s 27 species of Strepsiptera belong to the Stylopidae (Straka 2019), the largest family of twisted-wing parasites comprising 163 known species in nine genera: Crawfordia Pierce, 1908; Eurystylops Bohart, 1943; Hal- ictoxenos Pierce, 1909; Hylecthrus Saunders, 1850; Jantarostylops Kulicka, 2001; Kinzelbachus Özdikmen, 2009; Melittostylops Kinzelbach, 1971; Rozeia Straka, Jůzova & Batelka, 2014; and Stylops Kirby, 1802 (Kathirithamby 2018). Members of Stylopidae parasitize bees (Hymenoptera) of four families: Andrenidae, Colletidae, Halictidae, and Melittidae (Kathirithamby 2018). Stylops is the largest genus with as many as 117 described species, and most parasitize mining bees of Andrena (Kathirithamby 2018). -

(Strepsiptera: Stylopidae) from Dominican Amber

March - April 2010 227 SYSTEMATICS, MORPHOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY New Fossil Stylops (Strepsiptera: Stylopidae) from Dominican Amber MARCOS KOGAN1, GEORGE POINAR JR2 1Integrated Plant Protection Center and Dept of Horticulture; 2Dept of Zoology. Oregon State Univ, Corvallis, Oregon, 97331, USA; [email protected]; [email protected] Edited by Roberto A Zucchi Neotropical Entomology 39(2):227-234 (2010) ABSTRACT - Description of a new species of the genus Stylops from Dominican amber expands the number of families of this order represented by fossils of the mid-Eocene in the Neotropical region. The specimen described herein is reasonably well preserved, except for the tip of the abdomen that hampered observation of the aedeagus. The specimen fi ts defi nition of the comtemporary genus Stylops and differs from a related species, Jantarostylops kinzelbachi Kulicka, from Baltic amber, by the larger number of ommatidia, relative proportion of antennal segments, and venation of hind wings. The specimen differs from other contemporary species of Nearctic Stylops in, among other characters, the smaller size, sub-costa detached from costa and maxillary structure. Discovery of this fossil species of Stylops provides evidence of a possibly more temperate climate in the Antilles, since most contemporary species of the genus occur predominantly in the temperate zones of the Nearctic, Palearctic, and Oriental regions. All known species of the genus parasitize bees of the genus Andrena (sensu lato). Existence of a fossil andrenid, Protandrena eickworti Rozen Jr, of the same Dominican amber, offers evidence of a potential host for this new species of Stylops. KEY WORDS: Fossil insect, Neotropical Strepsiptera, Jantarostylops, Protandrena For a relatively rare group of insects, Strepsiptera are and male puparium in planthoppers of two families: well represented in the Dominican amber (Table 1). -

Observer Cards—Bees

Observer Cards Bees Bees Jessica Rykken, PhD, Farrell Lab, Harvard University Edited by Jeff Holmes, PhD, EOL, Harvard University Supported by the Encyclopedia of Life www.eol.org and the National Park Service About Observer Cards EOL Observer Cards Observer cards are designed to foster the art and science of observing nature. Each set provides information about key traits and techniques necessary to make accurate and useful scientific observations. The cards are not designed to identify species but rather to encourage detailed observations. Take a journal or notebook along with you on your next nature walk and use these cards to guide your explorations. Observing Bees There are approximately 20,000 described species of bees living on all continents except Antarctica. Bees play an essential role in natural ecosystems by pollinating wild plants, and in agricultural systems by pollinating cultivated crops. Most people are familiar with honey bees and bumble bees, but these make up just a tiny component of a vast bee fauna. Use these cards to help you focus on the key traits and behaviors that make different bee species unique. Drawings and photographs are a great way to supplement your field notes as you explore the tiny world of these amazing animals. Cover Image: Bombus sp., © Christine Majul via Flickr Author: Jessica Rykken, PhD. Editor: Jeff Holmes, PhD. More information at: eol.org Content Licensed Under a Creative Commons License Bee Families Family Name # Species Spheciformes Colletidae 2500 (Spheciform wasps: Widespread hunt prey) 21 Bees Stenotritidae Australia only Halictidae 4300 Apoidea Widespread (Superfamily Andrenidae 2900 within the order Widespread Hymenoptera) (except Australia) Megachilidae 4000 Widespread Anthophila (Bees: vegetarian) Apidae 5700 Widespread May not be a valid group Melittidae 200 www.eol.org Old and New World (Absent from S. -

Hymenoptera: Vespidae) Workers

THE LIFE HISTORY OF POLISTES METRICUS SAY: A STUDY OF BEHAVIOR AND PARASITIC NATURAL ENEMIES by AMANDA COLEEN HODGES (Under the direction of KARL ESPELIE) ABSTRACT The ability to recognize nestmates is an integral component of eusocial insect societies. Cuticular hydrocarbon profiles are believed to be important in the recognition process and these profiles have been shown to differ by age for some Polistes species. The effects of age on nest and nestmate discrimination are examined for Polistes metricus Say (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) workers. Age affected nest discrimination. Older (10-day old) P. metricus workers spent significantly more time on their natal nest than than younger (3-day old) workers. However, nestmate discrimination did not occur for either younger or older P. metricus workers. The lack of nestmate discrimination exhibited by either age class of workers emphasizes the potential role of a social insect’s environment in the recognition process. Brood stealing, parasitism pressures, resource limitations, and other environmental factors are eliminated in a homogenous laboratory setting. Polistes wasps are considered beneficial generalist predators, and the majority of their prey consists of lepidopteran larvae. The prevalence and occurrence of parasitic natural enemies are reported for early-season collected colonies of P. metricus. The strepsipteran, Xenos peckii Kirby, the ichneumonid Pachysomoides fulvus Cresson, the pyralid Chalcoela pegasalis Walker, and the eulophid Elasmus polistis Burks were present in P. metricus colonies. Xenos infestations have previously been thought to be infrequent, but X. peckii was the most predominant parasite or parasitoid over a four-year period. Life history information concerning the host-parasite relationship between X. -

Proceedings of the HAWAIIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY for 1961

Proceedings of the HAWAIIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY for 1961 VOL. XVIII, No. 1 AUGUST, T962 Suggestions for Manuscripts Manuscripts should be typewritten on one side of standard-size white bond paper, double or triple spaced, with ample margins. The sheets should not be fastened together; they should be mailed flat. Pages should be numbered con secutively. Inserts should be typed on separate pages and placed in the manu script in the proper sequence. Footnotes should be numbered consecutively and inserted in the manuscript immediately below the citation, separated from the text by lines. They should be used only where necessary. All names and references should be checked for accuracy, including diacritical marks. Authors' names must be spelled out when first mentioned. Illustrations should be planned to fit the type page, Wl x 7 inches. They should be drawn to allow for at least one-third reduction. Each should be labeled on the back with the author's name and title of the paper, as well as the number of the figure referred to in the text. Where size or magnification is important, some indication of scale should be given. They should be num bered consecutively, using capital letters to indicate parts of a composite figure. Printed letters are available from the Secretary. Legends should be typed on a separate sheet of paper and identified by the figure number. Tables and graphs should be used only where necessary and omitted if essentially the same information is given in the paper. Graphs and figures should be drawn in India ink on white paper, tracing cloth, or light blue cross-hatched paper. -

Order STREPSIPTERA Manual Versión Española

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 62B (30-06-2015): 1–10. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Class: Insecta Order STREPSIPTERA Manual Versión española CLASS INSECTA Order Strepsiptera Jeyaraney Kathirithamby1, Juan A. Delgado2,3 2,4 & Francisco Collantes 1 Department of Zoology, Universityu of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK [email protected] 2 Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, (España) 3 [email protected] 4 [email protected] 1. Short group definition and main diagnostic characters Strepsiptera are entomophagous parasitoids with free-living adult males and endoparasitic females (except in the family Mengenillidae). The hosts of this group are referred in the bibliography as “stylopized”; the two more frequently parasitized insect order are Homoptera and Hymenoptera. The males have large raspberry-like eyes, flabellate antennae, shortened forewings resembling dip- teran halteres and large hind wings (Fig. 2A and 2C). The females are neotenic and endoparasitic in the suborder Stylopidia. The endoparasitic females are divided into two regions: a sacciform body, which is endoparasitic in the host and an extruded cephalothorax (Fig. 4). In the extant family Mengenillidae both males and females (Fig. 2A and 2B) emerge from the host to pupate externally, and the neotenic females of this family are, as the males, free living (Kinzelbach, 1971, 1978; Kathirithamby, 1989, 2009). Last molecular studies confirm the sister group relationships of Strepsiptera with Coleoptera. Both lineages split from a common ancestor during the Permian (Wiegmann et al., 2009; Misof et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the fossil record of this group is restricted to only a few specimens preserved in amber. -

References Van Aarde, R

Hispine References Van Aarde, R. J., S. M. Ferreira, J. J. Kritzinger, P. J. van Dyk, M. Vogt, & T. D. Wassenaar. 1996. An evaluation of habitat rehabilitation on coastal dune forests in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Restoration Ecology 4(4):334-345. Abbott, W. S. 1925. Locust leaf miner (Chalepus doraslis Thunb.). United States Department of Agriculture Bureau of Entomology Insect Pest Survey Bulletin 5:365. Abo, M. E., M. N. Ukwungwu, & A. Onasanya. 2002. The distribution. Incidence, natural reservoir host and insect vectors of rice yellow mottle virus (RYMV), genus Sobemovirus in northern Nigeria. Tropicultura 20(4):198-202. Abo, M. E. & A. A. Sy. 1997. Rice virus diseases: Epidemiology and management strategies. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 11(2/3):113-134. Abdullah, M. & S. S. Qureshi. 1969. A key to the Pakistani genera and species of Hispinae and Cassidinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), with description of new species from West Pakistan including economic importance. Pakistan Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research 12:95-104. Achard, J. 1915. Descriptions de deux Coléoptères Phytophages nouveaux de Madagascar. Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France 1915:309-310. Achard, J. 1917. Liste des Hispidae recyeillis par M. Favarel dans la region du Haut Chari. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France 86:63-72. Achard, J. 1921. Synonymie de quelques Chrysomelidae (Col.). Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France 1921:61-62. Acloque, A. 1896. Faune de France, contenant la description de toutes les espèces indigenes disposes en tableaux analytiques. Coléoptères. J-B. Baillière et fils; Paris. 466 pp. Adams, R. H. -

Nine New Species of the Genus Stylops

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository NINE NEW SPECIES OF THE GENUS STYLOPS (STREPSIPTERA : STYLOPIDAE) PARASITIC ON THE GENUS ANDRENA (HYMENOPTERA : ANDRENIDAE) OF JAPAN (Studies on the Japanese Strepsiptera X) Kifune, Teiji Hirashima, Yoshihiro http://hdl.handle.net/2324/2467 出版情報:ESAKIA. 23, pp.45-57, 1985-11-30. Hikosan Biological Laboratory, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University バージョン: 権利関係: ESAKIA, (23) : 45-57. 1985 45 NINE NEW SPECIES OF THE GENUS STYLOPS (STREPSIPTERA : STYLOPIDAE) PARASITIC ON THE GENUS ANDRENA (HYMENOPTERA : ANDRENIDAE) OF JAPAN (Studies on the Japanese Strepsiptera X)* TEI JI KIFUNE Department of Parasitology, School of Medicine, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka 814-01, Japan and Y OSHIHIRO H IRASHIMA Entomological Laboratory, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 812, Japan Abstract Nine new species of the genus Stylops (Strepsiptera : Stylopidae) are described from 10 species of the Japanese Andrena (Hymenoptera : Andrenidae). Those are : S. japonicus sp. n. from A. (Andrena) benefica, S. truncatus sp. n. from A. (A.) maukensis, S. oblon- guhs sp. n. from A. (A.) Zongitibialis, S. truncatoides sp. n. from A. (A.) shirozui, S. circularis sp. n. from A. (Gymnandrena) sasakii, S. yamatonis sp. n. from A. (Simandrena) yamato, S. kaguyae sp. n. from A. (Mcrandrena) kaguya and A. (M.) minutula, S. borealis sp. n. from A. (Taeniandrena) ezoensis, and S. valerianae sp. n. from A. (Holandrena) valeriana. All of these are described from females excepting only S. borealis which is known by both sexes. Although not a few papers have been published on the Strepsiptera of Japan, no one has been contributable to the taxonomy of the genus stylops, the largest and best known one amongst the order of the world. -

Revisions of Two Subgenera of Andrena: Micrandrena Ashmead and Derandrena, New Subgenus (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 10-1968 Revisions of Two Subgenera of Andrena: Micrandrena Ashmead and Derandrena, New Subgenus (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) David O. Ribble Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumbulletin Part of the Entomology Commons, Geology Commons, Geomorphology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, Paleontology Commons, and the Sedimentology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BULLETIN OF VOLUME S , NUMBER S The University of Nebraska State Museum OCTOBER. 1968 David W. Ribble Revisions of Two Subgenera of Andrena: Micrandrena Ashmead and Derandrena, New Subgenus (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) David W. Ribble Revisions of Two Subgenera of Andrena: Micrandrena Ashmead and Derandrena, New Subgenus (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) BULLETIN OF The University of Nebraska State Museum VOLUME 8, NUMBER 5 OCTOBER 1968 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep appreciation to Dr. W. E. LaBerge of the Illinois Natural History Survey, Urbana (formerly of the University of Nebraska, Lincoln), for his interest, encourage ment and guidance during the course of this study, and for reading and making suggestions in the manuscript. Thanks are due Dr. R. E. Hill, who kindly assumed the responsibilities of committee chair man on Dr. LaBerge's departure. Appreciation is also due Dr.