Canterbury's Archaeology 1998 – 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Polhill, Fifth Son

180 THE POLHILL, OR POi.LEY, AND DE BOKELAND FAMILIES, DE• DUCED FROM THE VISITATION OF KENT IN 1619, BY PHILPOT, AND OF 1633; FROM HASTED AND HARRIS' HISTORIES OF KENT, BERRY'S KENTISH PEDIGREES, AND ADD, MS, 57ll, &,c, THE late eminent literary veteran and historian of Cornwall, the Rev. Richard Polwhele, of Polwhele, entertained an almost decided opinion, not only from the traditions of his family, but from other circumstances, that the Polhills of Kent were a branch of the Cornish Polwheles, which emigrated from the western into the eastern counties at a very early period; in an• cient deeds of his family, the name is spelt sometimes Polwhele, and sometimes Polhill, and the manor of Polwhele in Domesday Book is called " Polhel : " this manor was occupied under Ed• ward the Confessor by Winu» de Polhall (Polwel or Polwyl). In the time of the Empress Maud, J 140, Drogo de Polwhele, who was her Chamberlain, had large grants of lands from her; and this Drogo is the ancestor of the Polwheles 'of Polwhele, and, upon the authority cited, of the Polhills of Kent and Sussex. At what period of time this branch of the family settled in Kent it is difficult to say; but, as it is one of the most ancient in the county, it must have been at a very early period, at or pre• viously to the reign of Edward III. for in a charter in the Brit. Mus. xxvi. 30, 7 Edw. III. amongst other names, appear those of " Edmundi de Polle," and " Richardi de Bocland," the name having been spelt sometimes Polley, and sometimes Polhill. -

Copy of 11 Sum 01B.P65

Summer 2011 NEWSLETTER Rachel Beer - the Tunbridge Wells Connection You probably saw reviews of this book in the quality newspapers recently - it seems to have been very well received. It tells the story of Mrs Rachel Beer, a young Jewish women of very wealthy background who edited The Sunday Times and The Observer simultaneously in the 1890s. It is a tragic tale telling of her decline and breakdown after the death of her husband, and the rather uncaring attitude of many in her family, including Siegfried Sassoon. What you may not have realised is that there is a significant Tunbridge Wells connection. Rachel Beer lived here for over twenty years, though in a rather subdued way, first in Earls Court and then Chancellor House. The authors, Eilat Negev and Yehuda Koren, visited the town in 2008 as part of their research. Garden Party This year our Garden Party is on Saturday 23rd July at Mabledon. We are very grateful to Mr Hari Saraff for allowing us to use the grounds of this impressive Decimus Burton building for our annual event. Tickets are £10 each and are available from Frances Avery, at: 16 Great Courtlands, Langton Green, Tunbridge Wells, TN3 0AH. Tel. 01892 862530. Please make cheques payable to RTWCS, and include a sae. Front cover: Grosvenor Recreation Ground - see page 14. 2 Contents Personally Speaking ... 4 From the Planning Scrutineers by Gill Twells ... 5 Chairman’s Letter by John Forster ... 6 Putting Heritage First ... 8 Fiona Woodfield on using heritage to encourage regeneration Finding Henry ... 10 Peter and Michèle Clymer discover the history of their house Grosvenor Recreation Ground .. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Archaeological Journal on the Differenes of Plan Alleged to Exists

This article was downloaded by: [Northwestern University] On: 11 February 2015, At: 00:38 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Archaeological Journal Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 On the Differenes of Plan Alleged to exists Between Churches of Austin Canons and those of Monks; and the Frequency with which Such Churches were Parochial the Rev. J. F. Hodgson Published online: 15 Jul 2014. To cite this article: the Rev. J. F. Hodgson (1884) On the Differenes of Plan Alleged to exists Between Churches of Austin Canons and those of Monks; and the Frequency with which Such Churches were Parochial, Archaeological Journal, 41:1, 374-414, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1884.10852146 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1884.10852146 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Minutes PDF 77 KB

TONBRIDGE AND MALLING BOROUGH COUNCIL COUNCIL MEETING Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015 At the meeting of the Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council held at Civic Suite, Gibson Building, Kings Hill, West Malling on Tuesday, 3rd November, 2015 Present: His Worship the Mayor (Councillor O C Baldock), the Deputy Mayor (Councillor M R Rhodes), Cllr Mrs J A Anderson, Cllr Ms J A Atkinson, Cllr M A C Balfour, Cllr Mrs S M Barker, Cllr M C Base, Cllr Mrs P A Bates, Cllr Mrs S Bell, Cllr R P Betts, Cllr T Bishop, Cllr P F Bolt, Cllr J L Botten, Cllr V M C Branson, Cllr Mrs B A Brown, Cllr T I B Cannon, Cllr M A Coffin, Cllr D J Cure, Cllr R W Dalton, Cllr M O Davis, Cllr Mrs T Dean, Cllr T Edmondston- Low, Cllr B T M Elks, Cllr Mrs S M Hall, Cllr S M Hammond, Cllr Mrs M F Heslop, Cllr N J Heslop, Cllr S R J Jessel, Cllr D Keeley, Cllr Mrs F A Kemp, Cllr S M King, Cllr D Lettington, Cllr Mrs S L Luck, Cllr B J Luker, Cllr D Markham, Cllr P J Montague, Cllr Mrs A S Oakley, Cllr L J O'Toole, Cllr M Parry-Waller, Cllr S C Perry, Cllr H S Rogers, Cllr R V Roud, Cllr Miss J L Sergison, Cllr T B Shaw, Cllr Miss S O Shrubsole, Cllr C P Smith, Cllr Ms S V Spence, Cllr A K Sullivan, Cllr M Taylor, Cllr F G Tombolis, Cllr B W Walker and Cllr T C Walker Apologies for absence were received from Councillors D A S Davis and R D Lancaster PART 1 - PUBLIC C 15/65 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest made in accordance with the Code of Conduct. -

Kentish Homes Visited by the Staff and Nurses of the Ontario Military Hospital, Orpington, Kent, in 1916

THOMAS J. BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/kentishhomesvisiOOOOunse KENTISH HOMES // KENTISH HOMES VISITED BY THE STAFF AND NURSES OF THE ONTARIO MILITARY HOSPITAL ORPINGTON, KENT, IN 1916 EDITED BY CHARLES J. PHILLIPS MEMBER OF THE COUNCIL, KENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LONDON PRIVATELY PRINTED 1917 Tff«m DEDICATED TO LIEUT.-COLONEL D. W. AND MRS. McPHERSON AND THE STAFF, DOCTORS AND NURSES OF THE ONTARIO MILITARY HOSPITAL AT ORPINGTON WHO TO THE NUMBER OF OVER ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY HAVE LEFT THEIR HOMES AND IN MANY CASES HAVE SACRIFICED LUCRATIVE APPOINTMENTS TO HELP OUR BRAVE WOUNDED Combe Bank, Near Sevenoaks. Jan. \6th, 1917. TO THE OFFICERS AND NURSING STAFF OF THE ONTARIO MILITARY HOSPITAL Your prolonged stay in this country, in pursuance of the invaluable service you are rendering to those wounded in the course of the war, has given me the opportunity of the further realization of a long-felt wish to make you, who came from your Dominion, acquainted with some of the more historic and intimate phases of our old Mother Country, by showing you the ancestral homes of those to whom much of the greatness of our Empire is due. We have been equally fortunate in securing such a learned and able cicerone as Mr. Phillips has proved to be in arranging these excursions for us, and I welcomed his suggestion, which he has undertaken as a labour of love, of producing this little volume as a memento of the places we have visited. -

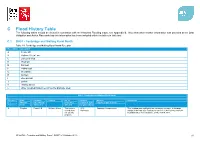

Flood History Table the Following Tables Should Be Viewed in Correlation with the Historical Flooding Maps, See Appendix B

C Flood History Table The following tables should be viewed in correlation with the Historical Flooding maps, see Appendix B. Note that where further information was provided at the Data Validation and Action Plan workshop this information has been included within the tables in italic text C.1 DA01 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural North Table C 1 Tonbridge and Malling Rural North Receptor Receptor Location A Pease Hill B Hatham Green Lane C Labour-in-Vain D Wrotham E Fairseat F Holborough G Wouldham H Burham I Blue Bell Hill J Eccles K Pratling Street L Other (isolated incidences across the drainage area) DA01 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural North Receptor, Date Location Source No. of Source Source Comments see (Month/ (Area/Road/ properties supplied data supplied data (report) Table C 1 Year) Street etc) affected (organisation) A Regular Pease Hill Surface Water This historic KCC Drainage Hotspots.xlsx This location was highlighted as a drainage hotspot. A drainage record does Highways hotspot is defined as a flood prone section of the highway network. not specify Definition taken from Guidance on the HMEP 2012. property flooding 2012s6726 - Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP (v1.0 October 2013) viii DA01 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural North Receptor, Date Location Source No. of Source Source Comments see (Month/ (Area/Road/ properties supplied data supplied data (report) Table C 1 Year) Street etc) affected (organisation) A 2012 Pease Hill Surface Water This historic KCC Sevenoaks 2012 P1.xls KCC was requested to clear flood water, cleanse and jet the gullies. with blocked record does Highways gullies/drains not specify property flooding B Regular Hatham Other There are Kent County Tonbridge_and A Pond on north side filled to capacity and water flowed into adjacent Green Lane records of a Council _Malling_SWM P_KCC_Highw property. -

THE LADIES De CLARE & the POLITICS of the 14Th CENTURY

THE LADIES de CLARE & THE POLITICS OF THE 14th CENTURY lot has been written about the Despenser’s and Piers Gaveston (who even has a ‘secret’ Society named after him), so it seems pointless repeating much of it here, but I have often A wondered what their wives, Eleanor and Margaret de Clare thought of what their respective husbands were up to, and whether the two sisters ever met to discuss their plight whilst they were near neighbours at Woking and Byfleet? Eleanor de Clare was the eldest daughter of Eleanor was a great favourite of her uncle, The Coat of Arms of Gilbert de Clare (the 6th Earl of Hertford, 7th Earl Edward II, who apparently ‘paid her living Gilbert de Clare, 7th of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan), and his expenses throughout his reign’, with payments Earl of Hertford, 8th second wife Joan of Acre, who was the daughter being made from the Royal Wardrobe accounts Earl of Gloucester. of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was for clothes and other items – a privilege that born in 1292 at Caerphilly Castle and in 1306 even his two sisters didn’t enjoy! She was the at the age of thirteen or fourteen was married principal lady-in-waiting to Queen Isabella and to Hugh le Despenser the Younger when he was even had her own retinue, headed by her own Countess of Cornwall. Instead Edward II gave about twenty. chamberlain, John de Berkenhamstead. her Oakham Castle and from 1313 to 1316 she was High Sheriff of Rutland. As a grand-daughter of Edward I she was Margaret de Clare was the second eldest de obviously quite a catch for the Younger Clare daughter. -

Catalogue of the Kent Archaeological

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society CATALOGUE 01? THE KENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY'S COLLECTIONS AT MAIDSTONE. BY G-EORGE PAYNE, E.L.S., E.S.A., HONORABY SECRETARY. AUD CHIEF CTJUATOK. LONDON: MITCHELL AND HUGHES, 140 "WAEDOTJE STEEET, W. 1892. CATALOGUE OF THE %mt grcfmeolofltcal &ocitt£& Collections at ifflafogtone. INTEODTTCTION. THE Museum of the Kent Archaeological Society was commenced in the year 1859, the Collection of Antiquities presented to the Society by the late "William Bland, Esq., of Hartlip, forming the nucleus of it. Since that time it has been enriched by donations from various gentlemen, whose names will be found mentioned in the Catalogue. The Society's researches and explorations, in the eastern portion of the county, have yielded a vast number of im- portant remains, all of which have been deposited in the Museum through the liberality of those on whose lands the objects were discovered. The British or Pre-Eoman period is represented by a magnificent series of gold armillse and torques in the highest state of preservation; also a small collection of early gold,coins. Among the remains of the Eomano-British period, special attention must be drawn to the fragments of a bronze statue found at Eichborough ; these have hitherto escaped observation. The intaglio from Eoches- ter is rare and curious, and the fragment of embossed glass from Hartlip is an interesting example of ancient art. A descriptive account of all these rarities is given in the Catalogue. The Anglo- Saxon period is thoroughly representative, and takes rank with the celebrated "Faussett" and "Gibbs" Collections, which are now, respectively, in the Liverpool aud South Kensington Museums. -

Archives Catalogue 16-04-2021 Notes 1 the Catalogue Lists Material Held

Tonbridge Historical Society: Archives Catalogue 16-04-2021 Notes 1 The catalogue lists material held by the Society. It is a work-in-progress. This version was compiled on 16 April 2021. 2 All codes should be prefixed by THS/ 3 Codes given in square brackets in some entries refer to former numbering schemes, now obsolete. 4 The catalogue is in three sections: Section 1 – Material organised by content thus: B: Business, Trade and Industry B/01 Trade B/02 Professions B/03 Cattle Market B/04 Manufacturing/Industry B/05 Chamber of Trade B/06 Banking E: Estate and property E/01 - E/50 H: Town History H/01 Books and pamphlets H/02 Newspapers H/03 Prints H/04 People and families H/05 World War I and II memorabilia H/06 Houses and buildings H/07 Local history research H/08 Folded Maps H/09 Royal Visits H/10 War memorials H/11 Rolled maps and plans H/12 Politics H/13 Archaeological Reports LG: Local Government LG/01 Wartime measures LG/02 Local Board LG/03 TUDC LG/04 Parish Vestry LG/05 Ad Hoc Organisations LG/06 TMBC LG/07 see below (Plans) LG/08 ?Manor Court LG/09 Cottage Hospital (Queen Victoria C H) Q: Charity and Education Q/ADU Adult Education /01 Adult School Union Q/CHA Charities /01 William Strong’s Charity /02 Elizabeth Clarke’s Charity /03 Sir Thomas Smythe’s Charity /04 Petley and Deakin’s Almshouses 1 /06 War Relief Fund Q/GEN General Charity and Education Q/INF Infant Schools /01/ Wesleyan Infants’ School Q/PRI Primary/Elementary Schools /01 St Stephen’s Schools /02 National School /03 Hildenborough CE. -

Lesnes Abbey

E S N E S B B E Y N I I K N THE PAR SH O F ER TH , E T E C LA PHA M P A FR D W . L . S . A . , e n the om lete e ort of the Invest at ons rc h tec t ral B i g C p R p ig i , A i u a nd stor c al c arr ed ou t b the W o rk s omm ttee of the Hi i , i y C i Wo olwic h Antiquarian S oc iety du ring the years 1 9 0 9 - 1 9 1 3 LO N DON T HE CA S S I O PR E SS , FR C S W RE DER M GER AN I . A , ANA , LAMB ’ S C N D UIT STR E ET W O . C . 5 , l 9 l 5 C ON T EN T S INTR OD UCTI O N LI ST OF ILLUS TR ATI ONS THE ABBE Y THE SITE AF TE R THE DIS S OLUTION BUI LD INGS PR E CINCT GRE AT BAR N CHUR CH ‘ CLOISTE R THE SACR I S TY CHAPTE R -HOUS E PAR LO UR D ORTE R AN D WAR MI NG-HOUS E RE R E -D ORTE R FR ATE R KI TCHE N WES TE R N RAN GE INF I R MAR Y MI S E R I COR D ’ ABBOT S LOD GING WATE R SUP PLY III— OBJE CTS F O UN D IN THE EXCAVATI ON S ' (i) S E P ULCHR AL MoNUME NTs (ii) PAVING TILE S (iii) GLAS S (iv) AR CHITE CTURAL FR AGME NTS (v) MIS CE LLANE OUS OBJE CTS A — OF O E PP E D S S TC . -

Tonbridge Circular Via Tudeley Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Tonbridge Circular via Tudeley walk A unique church, orchards and a country park of historical interest in the Garden of England. Length Main Walk: 19¼ km (12.0 miles). Four hours 30 minutes walking time. For the whole excursion including trains, sights and meals, allow at least 8½ hours. Long Walk, extended via Capel: 25¼ km (15.7 miles). Six hours walking time. OS Maps Explorers 136 (for Tudeley and Capel) & 147 (for Haysden). Tonbridge, map reference TQ587460, is in Kent, 10 km SE of Sevenoaks. Toughness 3 out of 10 (5 for the Long Walk). Features This varied walk takes in a low-lying area of parkland, farm fields, paddocks, orchards and a country park of historical interest in the Medway Valley around Tonbridge (pronounced Tunbridge: see Walk Notes). It is not a particularly scenic walk but it does include the chance to visit a unique church. There is nothing remarkable about the exterior of All Saints, Tudeley: an old guidebook described it as “obscure and unfrequented”. Nowadays the reverse is true, because its twelve stained glass windows were all designed by the great 20thC Russian artist, Marc Chagall. Initially commissioned by Sir Henry and Lady d'Avigdor-Goldsmid to create a single memorial window after the death of their daughter Sarah in 1963, Chagall was inspired to create windows for the entire church (as he had previously done for a synagogue in Jerusalem and a chapel in France). The final group of windows were dedicated in 1985, a few months after his death at the age of 98.