Toward Critical Theory for Public Folklore: an Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukrainian Folk Singing in NYC

Fall–Winter 2010 Volume 36: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore Ukrainian Folk Singing in NYC Hindu Home Altars Mexican Immigrant Creative Writers National Heritage Award Winner Remembering Bess Lomax Hawes From the Director Since the found- a student-only conference. There are prec- Mano,” readers will enjoy fresh prose pieces ing of the New York edents for this format, also. In commenting and poetry in English and Spanish from a Folklore Society, the on the 1950 meeting, then-president Moritz recently published anthology, produced by organization has pro- Jagendorf wrote, “Another ‘new’ at the Mexican cultural nonprofit Mano a Mano, vided two consistent Rochester meeting was the suggestion to the New York Writers Coalition, and a group benefits of member- have an annual contest among students of of New York’s newest Spanish-language ship: receipt of a New York State colleges and universities for writers. Musician, discophile, and Irish- published journal— the best paper on New York State folklore. American music researcher Ted McGraw since 2000, Voices— The winner will receive fifty dollars, and his presents a preliminary report and asks Voices and at least one annual meeting. or her paper will be read before the mem- readers for assistance in documenting the In the early years, the annual meeting bers.” (It is unclear whether this suggestion fascinating history of twentieth-century took place jointly with the annual gathering was implemented!) button accordions made by Italian craftsmen of the New York Historical Association, The 2010 meeting was held at New York and sold to the Irish market in New York. -

FOLK STUDIES 585: Public Folklore Policy and Practice in Washington DC Syllabus & Itinerary Winter 2015, January 9-23 Brent Bjorkman ([email protected])

FOLK STUDIES 585: Public Folklore Policy and Practice in Washington DC Syllabus & Itinerary Winter 2015, January 9-23 Brent Bjorkman ([email protected]) For years, folklorists have made it their lives’ work to help document, present and conserve the traditional arts and cultural heritage of our nation. Even from the earliest days of these passionate pursuits, key figures like Benjamin Botkin, chairman of the Federal Writer’s Project, helped to shape the importance and understanding of these vernacular expressions of culture and “insisted that democracy is strengthened by the valuing of myriad cultural voices” of Americans, not only those of a chosen few. Folklorists have recognized the need to create mechanisms at the national level to foster the growth of their efforts nationwide and to ensure that traditional arts and culture are a national priority. After the turn of the last half of the 20th century these notions to preserve and promote the traditional arts and culture of the country were furthered by the creation of folklife programs within federal cultural entities like the National Endowment for the Arts, the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian Institution. In this course, we will travel to the nation’s capital to explore the diverse range of work being done in the area of cultural policy as it relates to public folklore documentation, presentation and conservation by the folklife agencies based there. Over this five-day period the class will meet with a variety of cultural policy specialists from The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, National Endowment for the Arts, and the National Park Service, among others. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Masa Bulletin

masa bulletin IN THIS COLUMN we shall run discussions of MASSIVE MASA MEETING: As Yr. F. E. issues raised by the several chapters of the Amer writes this it is already two weeks beyond the ican Studies Association. This is in response to a date on which programs and registration forms request brought to us from the Council of the were to have been mailed. The printer, who has ASA at its Fall 1981 National Meeting. ASA had copy for ages, still has not delivered the pro members with appropriate issues on their minds grams. Having, in a moment of soft-headedness, are asked to communicate with their chapter of allowed himself to be suckered into accepting ficers, to whom we open these pages, asking only the position of local arrangements chair, he has that officers give us a buzz at 913-864-4878 to just learned that Haskell Springer, program alert us to what's likely to arrive, and that they chair, has been suddenly hospitalized, so that he keep items fairly short. will, for several weeks at least, have to take over No formal communications have come in yet, that duty as well. Having planned to provide though several members suggested that we music for some informal moments in the Spen prime the pump by reporting on the discussion cer Museum of Art before a joint session involv of joint meetings which grew out of the 1982 ing MASA and the Sonneck Society, he now finds that the woodwind quintet in which he MASA events described below. plays has lost its bassoonist, apparently irreplac- Joint meetings, of course, used to be SOP. -

AMERICAN FOLKLORE ARCHIVES in THEORY and PRACTICE Andy

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by IUScholarWorks ARCHIVING CULTURE: AMERICAN FOLKLORE ARCHIVES IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Andy Kolovos Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, Indiana University October 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee Gregory Schrempp, Ph.D. Moira Smith, Ph.D. Sandra Dolby, Ph.D. James Capshew, Ph.D. September 30, 2010 ii © 2010 Andrew Kolovos ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For my Jenny. I couldn’t have done it without you. iv Acknowledgements First and foremost I thank my parents, Lucy and Demetrios Kolovos for their unfaltering support (emotional, intellectual and financial) across this long, long odyssey that began in 1996. My dissertation committee: co-chairs Greg Schrempp and Moira Smith, and Sandra Dolby and James Capshew. I thank you all for your patience as I wound my way through this long process. I heap extra thanks upon Greg and Moira for their willingness to read and to provide thoughtful comments on multiple drafts of this document, and for supporting and addressing the extensions that proved necessary for its completion. Dear friends and colleagues John Fenn, Lisa Gabbert, Lisa Gilman and Greg Sharrow who have listened to me bitch, complain, whine and prattle for years. Who have read, commented on and criticized portions of this work in turn. Who have been patient, supportive and kind as well as (when necessary) blunt, I value your friendship enormously. -

Archie Green, a Botkin Series Lecture by Sean Burns, American Folklife

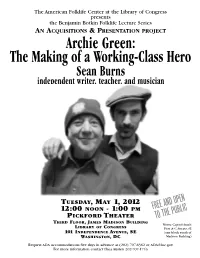

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress presents the Benjamin Botkin Folklife Lecture Series AN ACQUISITIONS & PRESENTATION PROJECT Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns independent writer, teacher, and musician TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012 D OPENFREE AN 12:00 NOON - 1:00 PM PICKFORD THEATER PUBLICTO THE THIRD FLOOR, JAMES MADISON BUILDING Metro: Capitol South LIBRARY OF CONGRESS First & C Streets, SE 101 I NDEPENDENCE AVENUE, SE (one block south of WASHINGTON, DC Madison Building) Request ADA accommodations five days in advance at (202) 707-6362 or [email protected] For more information contact Thea Austen 202-707-1743 Archie Green: The Making of a Working-Class Hero Sean Burns Respected as one of the great public intellectuals and his subsequent development of laborlore as a of the twentieth century, Archie Green (1917-2009), public-oriented interdisciplinary field. Burns will through his prolific writings and unprecedented explore laborlore’s impact on labor history, folklore, public initiatives on behalf of workers’ folklife, and American cultural studies and place these profoundly contributed to the philosophy and implications within the context of the larger “cultural practice of cultural pluralism. For Green, a child of turn” of the humanities and social sciences during Ukrainian immigrants, pluralism was the life-source the last quarter of the 20th century. When Green of democracy, an essential antidote to advocated in the late 1960s for the Festival of authoritarianism of every kind, which, for his American Folklife to include skilled manual laborers generation, most notably took the forms of fascism displaying their craft on the National Mall, this was and Stalinism. -

Rethinking the Role of Folklore in Museums: Exploring New Directions for Folklore in Museum Policy and Practice

Rethinking the Role of Folklore in Museums: Exploring New Directions for Folklore in Museum Policy and Practice A White Paper prepared by the American Folklore Society Folklore and Public Policy Working Group on Folklore and Museums Prepared by: Marsha Bol, C. Kurt Dewhurst, Carrie Hertz, Jason Baird Jackson, Marsha MacDowell, Charlie Seemann, Suzy Seriff, and Daniel Sheehy February 2015 2 Introduction The American Folklore Society’s working group on Folklore and Museums Policy and Practice has taken its cue from the growing number of folklorists who are working in and with museums to foster a greater presence for folklore in museum theory, practice, and policy. This work emerges from formal and informal conversations already underway among museum-minded folklorists. The Folklore and Museums Policy and Programs working group has been committed to synthesizing and extending these discussions through its activities and publications. Building upon past contributions by folklorists, the working group has held a series of regular phone conferences; a convening in Santa Fe in the fall of 2013 and a second convening in conjunction with the 2014 American Alliance of Museum’s Annual Meeting in Seattle; initiated a series of professional activities; conducted a series of sessions and tours related to folklife and museums for the 2014 American Folklore Society Meetings in Santa Fe; created a new Folklore and Museums Section of the Society; developed a working e-list of folklorists interested in a listserv on folklore and museums; and initiated or completed reports/publications to examine arenas where folklore can contribute to public and museum practice policies. A series of articles will be forthcoming on folklife and museums in Museum Anthropology Review (ed. -

Dr. Lisa Daly Cast Net Throwing with Alex Howse Storytelling with Dale Jarvis

WHO WE ARE Heritage Tomorrow NL supports the development of the next generation of heritage enthusiasts. Heritage Tomorrow NL works to build a network of post high-school-aged youth and emerging heritage professionals within the province. We strive to encourage and promote youth participation in Newfoundland and Labrador’s heritage field. PAGE ONE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 9:30AM: Registration 10:00AM: Introductions Morning Snacks/Caffeinated Beverages 10:30AM - 11:30AM: Learn Heritage Skills with Heritage-Bearers 11:30PM – 12:30PM: Lunch - Volcano Bakery “Adultier Adults” Shop Talk 12:30PM – 1:30PM: Heritage Skills Competition 1:30PM – 2:00PM: Closing Remarks Heritage Skills Winners Evaluations PAGE TWO hERITAGE SKILLS CHALLENGE A guaranteed-to-be-a-good-time activity (inspired by the Wooden Boat Museum) that introduces participants to heritage skills they will master within minutes! (Okay, maybe not “master”, but you’ll be better than you were before.) This year’s skills include: Cross-stitch with Katharine Harvey Northern Games with Peter Geetah a member of the St. John’s Native Friendship Centre Pot reconstruction (smash & fix!) with Dr. Lisa Daly Cast net throwing with Alex Howse Storytelling with Dale Jarvis Heritage bearers are on site to teach participants the task at hand. After learning from a pro, everyone will show-off their new-found skills in a timed challenge in the name of fun and friendly competition. AND PRIZES! PAGE THREE “adultier” adults shop talk Do you have questions about working in the heritage field? Are you looking for someone to share experiences with? Or maybe you just want to make some new friends! This session is a chance to pick the brains of your peers. -

Survey of Public Folklore Collections in the Upper Midwest 2005-2006 Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures University of Wisconsin-Madison Csumc.Wisc.Edu

Survey of Public Folklore Collections in the Upper Midwest 2005-2006 Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures University of Wisconsin-Madison csumc.wisc.edu Location of publicly-funded folklore fieldwork collections in the Upper Midwest Survey of Public Folklore Collections in the Upper Midwest 2005-2006 Author: Nicole Saylor Editors: Ruth E. Olson, Janet C. Gilmore, and Karen J. Baumann Online Adaptation: Mary Hoefferle, Karen J. Baumann, and Janet C. Gilmore Publisher: Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures 901 University Bay Drive Madison, WI 53705 http://csumc.wisc.edu The “Survey of Public Folklore Collections in the Upper Midwest, 2005- 2006” report was first printed and distributed in Summer 2007. This Winter 2009 online version of the survey includes modifications based on responses from survey participants. The publication of this report, and the survey on which it is based, were made possible with funding from a National Historical Publications and Records Commission grant, 2005-2006. Additional funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, and advisory assistance from folklorists and archivists regionally and nationally, have supported research leading to the survey and following from it. 2 INDEX Overview.......................................................................................................................................4 Survey Findings.............................................................................................................................8 Key to Collection Profile -

Resource Guide for Graduate Students and New Professionals

Professional Development in Folklore: A Resource Guide for Graduate Students and New Professionals Presented in conjunction with the Professional Development Sessions at the American Folklore Society 2003 Annual Meeting Albuquerque, New Mexico, October 9-10, 2003 Compiled by Laura R. Marcus, Program Associate The Fund for Folk Culture In collaboration with the American Folklore Society Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts Copyright The American Folklore Society, 2003 2 Professional Development in Folklore and Folklife: A Resource Guide for Graduate Students and New Professionals TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 3 Graduate Programs in Folklore in the US and Canada 4 National Folklore and Folklife Resources 5 Resources for Finding Funding and Employment Opportunities 9 Academic Folklore 12 Funding Resources for Scholarly Research 12 Additional Resources for Identifying Sources of Support For Scholarly Work 20 Career Resources 21 Scholarly Organizations Serving Allied Fields 21 Public and Applied Folklore 23 Funding Resources 25 Career Resources 30 Additional Service Organizations 31 A Word About Public, Applied, and Independent Folklorists Working in Alternative Professional Contexts 33 Acronym Cheat Sheet 35 3 PREFACE The American Folklore Society and the Fund for Folk Culture, with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, present A Resource Guide for Graduate Students and New Professionals, in conjunction with a series of Professional Development Sessions held at the 2003 American Folklore Society Meetings in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This guide is geared towards graduate students and to professionals who are at the beginning stages of their careers as professional folklorists. We hope that folklorists interested in pursuing academic, public/applied, or independent work will use this guide to locate educational, funding, and employment opportunities, and to familiarize themselves with the national, regional and local resources serving the field of folklore. -

"So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" a Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler

~~~~ 8 - ·t"§, · .. ~.JLJ.J.... ~ .... "So Long, It's Been Good to Know You" A Remembrance of Festival Director Ralph Rinzler RICHARD KURIN Our friend Ralph did not feel above anyone. He quickly became a symbol of the Smithsonian helped people to learn to enjoy their differ under Secretary S. Dillon Ripley1 energizing ences. "Be aware of your time and your place, II the Mall. It showed that the folks from back he said to every one of us. "Learn to love the beau home had something to say in the center of 1 ty that is closest to you. II So I thank the Lord for the nation S capital. The Festival challenged sending us a friend who could teach us to appre America1s national cultural insecurity. ciate the skills of basket weavers, potters, and Neither European high art nor commercial bricklayers - of hod carriers and the mud mix pop entertainment represented the essence of ers. I am deeply indebted to Ralph Rinzler. He did American culture. Through the Festival1 the not leave me where he found me. Smithsonian gave recognition and respect to - Arthel 11 Doc" Watson the traditions/ wisdom1 songs1 and arts of the American people themselves. The mammoth Lay down, Ralph Rinzler, lay down and take 1976 Festival became the centerpiece of the your rest. American Bicentennial and a living reminder of the strength and energy of a truly wondrous o sang a Bahamian chorus on the and diverse cultural heritage - a legacy not to National Mall at a wake held for Ralph be ignored or squandered. -

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 the WEST and WORKERS, 1870

1 James Gregory October 3, 2000 THE WEST AND WORKERS, 1870-1930, Blackwell Companion to the History of the American West, William Deverell, ed. (forthcoming) "Is there something unique about Seattle's labor history that helps explain what is going on?" the reporter for a San Jose newspaper asks me on the phone during the World Trade Organization protests that filled Seattle streets with 50,000 unionists, environmentalists, students, and other activists in the closing days of the last millennium. "Well, yes and no," I answer before launching into a much too complicated explanation of how history might inform the present without explaining it and how the West does have some particular traditions and institutional configurations that have made it the site of bold departures in the long history of American class and industrial relations but caution that we probably should not push the exceptionalism argument too far. "Thanks," he said rather vaguely as we hung up 20 minutes later. His story the next day included a twelve word quotation.1 The conversation, I realize much later, revealed some interesting tensions. Not long ago the information flow might have been reversed, the historian might have been calling the journalist to learn about western labor history, a body of 2 research that until the 1960s had not much to do with professional historians, particularly those who wrote about the West. And his disappointment at my long-winded equivocations had something to do with those disciplinary vectors. He had been hoping to tap into an argument that journalists know well but that academics have struggled with.