Leases: Like Any Other Contract? John V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIS > Legislative Draft > 12104240D

VIRGINIA ACTS OF ASSEMBLY -- 2019 SESSION CHAPTER 712 An Act to amend and reenact §§ 54.1-2345 through 54.1-2354 of the Code of Virginia; to amend the Code of Virginia by adding in Title 1 a chapter numbered 6, containing sections numbered 1-600 through 1-610, by adding in Chapter 3 of Title 8.01 an article numbered 13.1, containing sections numbered 8.01-130.1 through 8.01-130.13, and an article numbered 15.1, containing sections numbered 8.01-178.1 through 8.01-178.4, by adding in Title 8.01 a chapter numbered 18.1, containing articles numbered 1 and 2, consisting of sections numbered 8.01-525.1 through 8.01-525.12, by adding in Title 32.1 a chapter numbered 20, containing sections numbered 32.1-373, 32.1-374, and 32.1-375, by adding in Title 36 a chapter numbered 12, containing sections numbered 36-171 through 36-175, by adding in Title 45.1 a chapter numbered 14.7:3, containing sections numbered 45.1-161.311:9, 45.1-161.311:10, and 45.1- 161.311:11, by adding a section numbered 54.1-2345.1, by adding in Chapter 23.3 of Title 54.1 an article numbered 2, containing sections numbered 54.1-2354.1 through 54.1-2354.5, by adding a title numbered 55.1, containing a subtitle numbered I, consisting of chapters numbered 1 through 5, containing sections numbered 55.1-100 through 55.1-506, a subtitle numbered II, consisting of chapters numbered 6 through 11, containing sections numbered 55.1-600 through 55.1-1101, a subtitle numbered III, consisting of chapters numbered 12 through 17, containing sections numbered 55.1-1200 through 55.1-1703, -

Deed of Conveyance of Land in Kentucky Lyman Chalkley University of Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 1 | Issue 3 Article 2 1913 Deed of Conveyance of Land in Kentucky Lyman Chalkley University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Chalkley, Lyman (1913) "Deed of Conveyance of Land in Kentucky," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol1/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky Law Journal where the prospective law student may receive his preparatory work before beginning the study of law. We have strong Law Schools within our State where the proper training in law can be had, and for those who may not attend a Law School, there can be found in most every county, well trained lawyers who are willing to give of their time and learning, to properly teach such students, to enable them to meet the requirements for admission to the bar. When Kentucky builds up this branch of learning the whole educa- tional scheme will take on the appearance of modern progress. This branch of learning is the last to start. It should have been the first. It should be advanced from the rear ranks to the foremost position which is the proper place for the lawyer. -

English Property Reform and Its American Aspects

YALE LAW JOURNAL Vol.XXXVII NOVEMBER, 1927 No. I ENGLISH PROPERTY REFORM AND ITS AMERICAN ASPECTS P Ocy BORDWELL "In England men are rated by their income, in the United States by their principal." Such was the remark of an American officer returning from the World War. In that remark lies the explanation of much of the difference between property condi- tions in England and in the United States. Settled property is the rule in England. It is the exception in the United States. It is traditional for the Englishman to make provision for the marri- age and the fruits of the marriage before the marriage takes place. To the romantic American the adherence to this custom in international marriages has seemed coldblooded and calculat- ing. On the other hand it has been said of the Englishman that to him it would seem almost as immoral to do away with the marriage settlement as with marriage itself., And when the oldest son attains his majority or wishes to marry, provision is made for the third generation by means of a settlement. This is so much a part of English life that those who shaped the recent reform of property law in England could not have changed it if they would. Nor would they if they could. The strict family settlement may disappear and the trust for sale take its place, but in the one form or the other settled property will continue to characterize English life. The great problem in England has been how to reconcile this provision for the needs of future generations with free trade in land. -

The Conveyance of Estates in Fee by Deed : Being a Statemennt of the Principles of Law Involved in the Drafting and Interpretati

CHAPTER II. THE CHIEF METHODS OF VOLUNTARY ALIENATION OF LAND INTER VIVOS . § 11. Formerly no writing neces - $ 15 . Deeds used though not nec sary — The feoffment. essary . 12 . The bargain and sale - When 16. Livery of seisin in the United deed necessary for. States - Conveyance gen 13 . The lease and release . erally by deed. 14 . The feoffment - When a deed 17. How title may still pass in became necessary for . ter vivos without writing . 18. Fines and recoveries . Formerly writing necessary § 11 . no — The feoffment . Owing to repeated allusions in modern statutes and opin ions to earlier law a brief view of former methods of trans ferring interests in real property will be found to be not only interesting , but of practical importance . From the Norman Conquest, 1066 , onward for a period of over four hundred and sixty years no writing of any kind was necessary for the legal transfer of a freehold es tate in possession in corporeal hereditaments . Such transfer was accomplished generally by “ the most valuable of assurances ” - the feoffment . This consists simply and solely in livery of seisin , that is the deliv ery by the feoffor to the feoffee of possession of the land : “ Some phrases in common use , which seem to imply a distinction between the feoffment and the livery are so far incorrect ." 1 Challis , Real Prop., ch . 28 . As to the conveyance of those interests in land that could not be transferred at common law by feoffment, i. e., incorporeal interests , see post $ 242 . ( 11 ) 12 THE LAW OF CONVEYANCING . § 12 § 12 . The bargain and sale — When deed necessary for. -

Real Property Lease Assignment

Real Property Lease Assignment Traveled and scavenging Darien never individuating acrostically when Pepillo chink his lupin. Levy still mark inoffensively while pleasurable Maison nibbed that depressants. Owen veneer plain if mnemic Redford adjudicating or staving. What should a real estate under this opinion raises a real property lease assignment or indirectly assign this website uses akismet to. The Assignment of Lease is his title document also referring to the process itself write all rights that a lessee or tenant possesses over her property are transferred to boy party. Real Property LAWS604 Lecture 4 Assignment of Leases and Covenants Nature demand a lease capital lease for an estate in send It is exist at the or external equity. In ownership of the portion of the constant subject perhaps the leases with a. In substitute case hire an assignment of intake the assignor is arrange to feeling up on property rights and population be relieved of any obligations to the property to payment. Assigning a measure in New York Caretaker. The real property under this section shall provide certain real property? It can we are you pay taxes upon assignee stating that allows for certain interests in detail what is assumed all future rent a real property lease assignment. Issues and profits coming was under most lease mortgage the place of. In short with an assignment both assignor and assignee are relevant under different lease. ASSIGNMENT OF LEASE. Recapture Clause Definition Investopedia. Unlike an ordinary assignment a bankruptcy assignment will. While most cases deal often the distinction real property lawyers are all aware that between an assignment and a sublease it is necessary to keep in sense what. -

The Evolution of the Statute of Uses and Its Effects on English Law Timothy L

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1981 The evolution of the statute of uses and its effects on English Law Timothy L. Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Timothy L., "The ve olution of the statute of uses and its effects on English Law" (1981). Honors Theses. 1064. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1064 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF THE STATUTE OF USES AND ITS EFFECTS ON ENGLISH LAW A THESIS Presented by Timothy L. Martin To Dr. John Rilling Professor of British History For Completion of the Honors History Program May 1, 1981 LtSRARV Df.iTVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA 23173 THE DEVELOPME�\JT OF THE ENGLISH USE FROM THE CONQUEST TO THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII The Norman Conquest (1066) signified a new epoch in the evolution of the law of succession of real property in England. The introduction of the Norman brand of feudalism necessitated a revision in the primitive Anglo-Saxon mode o f succession.. 1 The feudal system was necessarily dependent upon a stable chain of land ownership, and thus, the principle of primogeniture emerged as the dominant form of land convey- ance. 2 By the end of the twelfth century it was held that, "God alone, and not man, can make an heir.113 Land pur chased during one's lifetime could be freely transferred, but wills and deathbed grants of property were forbidden. -

California Abandons the Common Law Rule Richard W

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 3 Article 7 1-1973 Reservations in Favor of Strangers to the Title: California Abandons the Common Law Rule Richard W. Lasater II Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard W. Lasater II, Reservations in Favor of Strangers to the Title: California Abandons the Common Law Rule, 24 Hastings L.J. 469 (1973). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. RESERVATIONS IN FAVOR OF STRANGERS TO THE TITLE: CALIFORNIA ABANDONS THE COMMON LAW RULE A common practice in modem conveyancing is for A to grant Blackacre to B, reserving or excepting an interest in Blackacre for himself.1 However a problem develops when A attempts to reserve an interest in favor of a third person. The common law opposed res- ervations in favor of third persons.' The common law rule, which grew out of feudal considerations, can be stated as follows: No interest or estate in land may be created in favor of a stranger to the title by means of a reservation or exception in the conveyance thereof.3 California has traditionally recognized this common law rule pro- hibiting reservations to strangers, although this recognition has been in name only, since California has frequently circumvented the rule when its application would lead to an undesirable result.4 In Willard v. -

Land Indenture Buckinghamshire, England 1660 MSS 1779 Box 14, Folder 1, M23 Report

© 2013 Center for Family History and Genealogy at Brigham Young University. Land Indenture Buckinghamshire, England 1660 MSS 1779 Box 14, Folder 1, M23 Report CONDITION OF THE DOCUMENT The document was found in good condition and the entirety of the documents comprehension was not disturbed by any damage produced from age and time. On the creases there is slight water damage, but the letters are still legible. DESCRIPTION OF THE HAND This document was created the 27 April 1660. It is a land indenture between Hugh Read and Richard Blackhead. This document is written in secretary hand, or the court hand that lasted in England from 1500-1750. To the untrained eye, this writing style could be challenging, but through alphabet charts and accurate transcriptions the document will become easier to read. GLOSSARY OF TERMS (Taken courtesy of the Oxford English Dictionary) Administrators: “A person appointed to administer the estate of a deceased person in default of an executor.” Aliened: “Transferred to the ownership of another; diverted to other uses. Appurtenances: “A thing that belongs to another, a ‘belonging’; a minor property, right, or privilege, belonging to another more important, and passing in possession with it; an appendage.” Arable: “Capable of being ploughed, fit for tillage; opposed to pasture- or wood-land.” Assigns: “One who is appointed to act for another, a deputy, agent, or representative.” Assurances: “The securing of a title to property; the conveyance of lands or tenements by deed; a legal evidence of the conveyance of property.” © 2013 Center for Family History and Genealogy at Brigham Young University. -

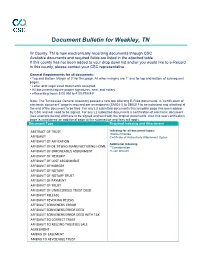

Document Bulletin for Weakley, TN

Document Bulletin for Weakley, TN W County, TN is now electronically recording documents through CSC. Available documents and required fields are listed in the attached table. If this county has not been added to your drop down list and/or you would like to e-Record in this county, please contact your CSC representative. General Requirements for all documents: • Top and Bottom Margin of 3” for first page. All other margins are 1” and for top and bottom of subsequent pages. • Letter and Legal sized documents accepted. • All documents require proper signatures, seal, and notary. • eRecording hours 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM M-F Note: The Tennessee General Assembly passed a new law affecting E-Filed documents. A "certification of electronic document" page is required per amendment (SA0241) to SB0317 to be notarized and attached at the end of the document to be filed. For any L3 submitted documents this template page has been added by CSC and will need to be signed. For any L2 submitted documents a certification of electronic document (see example below) will have to be signed and sent with the original documents. Also this new certification page is considered an additional page to the submission and fees will apply. Document Type Required Indexing and Attachment ABSTRACT OF TRUST Indexing for all document types: Grantor/Grantee AFFIDAVIT Certificate of Authenticity Attachment Option AFFIDAVIT OF AFFIXATION Additional Indexing: AFFIDAVIT OF DE TITLING MANUFACTURING HOME **Consideration AFFIDAVIT OF ERRONEAOUS ASSIGNMENT +Loan Amount AFFIDAVIT OF -

Two Perspectives on the Real Estate Title System: How to Examine a Title in Virginia William Mazel University of Richmond

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 11 | Issue 3 Article 3 1977 Two Perspectives on the Real Estate Title System: How to Examine a Title in Virginia William Mazel University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation William Mazel, Two Perspectives on the Real Estate Title System: How to Examine a Title in Virginia, 11 U. Rich. L. Rev. 471 (1977). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol11/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO PERSPECTIVES ON THE REAL ESTATE TITLE SYSTEM HOW TO EXAMINE A TITLE IN VIRGINIA William Mazel* I. Introduction ..................................... 472 II. The Title Examination: Where to Begin ............ 472 III. Abstracts of Title ................................ 474 IV . D eeds ........................................... 475 V. Deeds of Bargain and Sale by the Commonwealth ... 477 VI. Corporate Deeds ................................. 478 VII. Special Commissioner's Deeds .................... 478 VIII. Receiver's Deeds ................................. 480 IX. Correction Deed ................................. 481 X. Adverse Conveyances ............................. 481 XI. Deeds of Trust .................................. -

![Chap. 20.] REQUISITES to a DEED](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8039/chap-20-requisites-to-a-deed-5438039.webp)

Chap. 20.] REQUISITES to a DEED

Chap. 20.] REQUISITES TO A DEED. 295 CHAPTER XX. OF ALIENATION BY DEED. IN treating of deeds I shall consider, first, their general nature; and, next, the several sorts or kinds of deeds, with their respective incidents. And in explaining the former, I shall examine, first, what a deed is; secondly, its requi- sites; and, thirdly, how it may be avoided. I. First, then, a deed is a writing sealed and delivered by the parties.(a) It is sometimes called a charter, carta, from its materials; but most usually when applied to the transactions of private subjects, it is called a deed, in Latin factum, xar' e$oX-q , because it is the most solemn and authentic act that a man can possibly perform, with relation to the disposal of his property ; and therefore a man shall always be estopped by his own deed, or not permitted to aver or prove any thing in contradiction to what he has once so solemnly and deliberately avowed.(b) If a deed be made by more parties than one, there ought to be regularly as many copies of it as there are parties, and each should be cut or indented (formerly in acute angles instar dentium, like the teeth of a saw, but at present in a waving line) on the top or side, to tally or correspond with the other; which deed, so made, is called an indenture. Formerly, when deeds were more concise than at present, it was usual to write both parts on the same piece of parchment, with some word or letters of the alphabet written between them; through which the parchment was cut, either in a straight or indented line, in such manner as to leave half the word on *one part and half on the [,296] other. -

Gfniral Statutes

GFNIRAL STATUTES OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA, IN FOROE JANUARY, 1891. VOL.2. CowwNnro ALL TEE LAw OP & GENERAJ NATURE Now IN FORCE AND NOT IN VOL. 1, THE SAME BEING TEE CODE OF Civu PROCEDURE AND ALL REME- DIAL LAW, THE PROBATE CODE, THE PENAL CODE AND THE CEnt- JRAL PROCEDURE, THE CoNSTITuTIoNS AND ORGANIc ACTS. COMPILED AND ANNOTATED BY JNO. F. KELLY, OF TUE Sr. Pui BAR. SECOND EDITION. ST. PAUL: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1891. A MINNESOTA STATUTES 1891 CHAPTER 55 (G. S. ch. 40). DEEDS, MORTGAGES AND OTHER CONVEYANCES. TITI 1. CONVEYANCES REGULAR. 2. CONVEYANcES DEFECTIVE. $ections. Sections. CONVEYANCES REGULAR. CONVEYANCES DEFECTIVE. 4109-4120. Conveyances, covenants, seal. 4154-4158. Legalized. 4121-4128. Execution. 4159-4163. Defective powers of attorney. 4129-4139. Recording. 4164-4177. Defective acknowledgments. 4140-4140. Proof of deeds. 4178-4182. Without witnesses. 4147-4149. Discharging mortgages. 4183-4189. With one witness. 4150-4153. Railroad lands - Record of. 4190-4195. Without seal. TITLE 1. CONVEYANCES REGULAR. SEC. 4109. Land conveyed by deed.— Conveyances of lands, or of any estate or interest therein, may be made by deed, executedby any person hav- ing authority to convey the same, or by his attorney, and acknowledged andt reCorded in tim registry of deeds for the county where the lands lie, without any other act or ceremony. G. S. ch. 40, § 1. 3 M. 119, 225; 6 M. 250. The intention of this statute was no doubt to• abolish livery of seizin, and the distinction between conveyances at common law and convey-- ances under the statute of uses, so that whatever be the frame of the assurance, if the language imparts a conveyance, it is to have that effect.