Documenting Inuit Sign Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes Code Home Language OM (Afan) Oromo AB Abkhazian AC Abnaki AD Achumawi AA Afar AK Afrikaans AE Ahtena EF Akan EK Akateko AF Alabama AL Albanian, Shqip AG Aleut AH Algonquian WJ American Sign Language AM Amharic AI Apache AR Arabic AJ Arapaho AO Araucanian AP Arikara AN Armenian, Hayeren AS Assamese AQ Athapascan AT Atsina AU Atsugewi AV Aucanian WK Awadhi AW Aymara AZ Azerbaijani AX Aztec BA Bantu BC Bashkir BQ Basque, Euskera BS Bassa BJ Belarusian Code Home Language BE Bengali, Bangla BR Berber BP Bhojpuri DZ Bhutani BH Bihari BI Bislama BG Blackfoot BF Breton BL Bulgarian BU Burmese, Myanmasa BD Byelorussian CB Caddo CC Cahuilla CD Cakchiquel CA Cambodian, Khmer CN Cantonese EC Carolinian CT Catalan CE Cayuga ZA Cebuano ED Chamorro CF Chasta Costa CG Chemeheuvi CI Cherokee CJ Chetemacha CK Cheyenne ZB Chhattisgarhi ZC Chinese, Hakka ZD Chinese, Min Nau (Fukienese or Fujianese) CH Chinese, Zhongwen CL Chinook Jargon CM Chiricahua ZE Chittagonian CP Chiwere CQ Choctaw CS Chumash EE Chuukese/Trukese Code Home Language CU Clallam CV Coast Miwok CW Cocomaricopa CX Coeur D’Alene CY Columbia DF Comanche CO Corsican DG Cowlitz DJ Cree ZF Creole HR Croatian, Hrvatski DK Crow DH Cuna DI Cupeno CZ Czech DB Dakota DA Danish DL Deccan DC Delaware DD Delta River Yuman DE Diegueno DU Dutch, Netherlands DO Dzongkha EN English EA Eskimo EO Esperanto ES Estonian EB Eyak FO Faroese FA Farsi, Persian FJ Fijian FL Filipino FI Finnish, Suomi FB Foothill North Yokuts FC Fox FR French FD French Cree Code Home -

University of California Santa Cruz Minimal Reduplication

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MINIMAL REDUPLICATION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Jesse Saba Kirchner June 2010 The Dissertation of Jesse Saba Kirchner is approved: Professor Armin Mester, Chair Professor Jaye Padgett Professor Junko Ito Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Jesse Saba Kirchner 2010 Some rights reserved: see Appendix E. Contents Abstract vi Dedication viii Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Structureofthethesis ...... ....... ....... ....... ........ 2 1.2 Overviewofthetheory...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 2 1.2.1 GoalsofMR ..................................... 3 1.2.2 Assumptionsandpredictions. ....... 7 1.3 MorphologicalReduplication . .......... 10 1.3.1 Fixedsize..................................... ... 11 1.3.2 Phonologicalopacity. ...... 17 1.3.3 Prominentmaterialpreferentiallycopied . ............ 22 1.3.4 Localityofreduplication. ........ 24 1.3.5 Iconicity ..................................... ... 24 1.4 Syntacticreduplication. .......... 26 2 Morphological reduplication 30 2.1 Casestudy:Kwak’wala ...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 31 2.2 Data............................................ ... 33 2.2.1 Phonology ..................................... .. 33 2.2.2 Morphophonology ............................... ... 40 2.2.3 -mut’ .......................................... 40 2.3 Analysis........................................ ..... 48 2.3.1 Lengtheningandreduplication. -

Assessing the Bimodal Bilingual Language Skills of Young Deaf Children

ANZCED/APCD Conference CHRISTCHURCH, NZ 7-10 July 2016 Assessing the bimodal bilingual language skills of young deaf children Elizabeth Levesque PhD What we’ll talk about today Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bimodal bilingualism Bimodal bilingual assessment Measuring parental input Assessment tools Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bilingual literature generally refers to children’s acquisition of two languages as simultaneous or sequential bilingualism (McLaughlin, 1978) Simultaneous: occurring when a child is exposed to both languages within the first three years of life (not be confused with simultaneous communication: speaking and signing at the same time) Sequential: occurs when the second language is acquired after the child’s first three years of life Routes to bilingualism for young children One parent-one language Mixed language use by each person One language used at home, the other at school Designated times, e.g. signing at bath and bed time Language mixing, blending (Lanza, 1992; Vihman & McLaughlin, 1982) Bimodal bilingualism Refers to the use of two language modalities: Vocal: speech Visual-gestural: sign, gesture, non-manual features (Emmorey, Borinstein, & Thompson, 2005) Equal proficiency in both languages across a range of contexts is uncommon Balanced bilingualism: attainment of reasonable competence in both languages to support effective communication with a range of interlocutors (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2006; Grosjean, 2008; Hakuta, 1990) Dispelling the myths….. Infants’ first signs are acquired earlier than first words No significant difference in the emergence of first signs and words - developmental milestones are met within similar timeframes (Johnston & Schembri, 2007) Slight sign language advantage at the one-word stage, perhaps due to features being more visible and contrastive than speech (Meier & Newport,1990) Another myth…. -

Hawai'i Civil Rights Commission

,¢,..... € o F "‘‘“_ 1",,’ .. .4 Q,‘*- "0 /"I ,u' 4' ‘ .-‘$-@9359 \”,r 0 Q.-E - )‘\ ' 2‘_ ; . .J.(‘"1_.-' 1:" ._- '2-n44!‘ cull ? ‘ b mm.» HAWAI‘I CIVIL RIGHTS COMMISSION ,,.,,...,_ ‘ » $5‘. .._,,.. /\~ ,‘ ___\ ‘fife 830 PUNCHBOWL STREET, ROOM 411 HONOLULU, HI 96813 ·PHONE: 586-8636 FAX: 586-8655 TDD: 568-8692 $‘_,-"‘i£_'»*,, ,.‘-* A-_ ,a:¢j_‘f.§.......+9-.._ ~4~ -u--........~-‘Q; ,1'\n_.'9. February 24, 2021 Videoconference, 9:45 a.m. To: The Honorable Karl Rhoads, Chair The Honorable Jarrett Keohokalole, Vice Chair Members of the Senate Committee on Judiciary From: Liann Ebesugawa, Chair and Commissioners of the Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission Re: S.B. No. 537 The Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission (HCRC) has enforcement jurisdiction over Hawai‘i’s laws prohibiting discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and access to state and state funded services. The HCRC carries out the Hawai‘i constitutional mandate that no person shall be discriminated against in the exercise of their civil rights. Art. I, Sec. 5. S.B. No. 537 would add a new section to Chapter 1 of the Hawai‘i Revised Statutes which would recognize American Sign Language (ASL) as a fully developed, autonomous, natural language with its own grammar, syntax, vocabulary and cultural heritage. Just as is the case with languages that are characteristic of ancestry or national origin, ASL is a language that is closely tied to culture and identity. Over 40 US states recognize ASL to varying degrees, from a foreign language for school credits to the official language of that state's deaf population, with several enacting legislation similar to S.B. -

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

American Sign Language (ASL) 1

American Sign Language (ASL) 1 American Sign Language (ASL) Courses ASL A101 Elementary American Sign Language I 4 Credits Introductory course for students with no previous knowledge of American Sign Language (ASL). Develops receptive and expressive signing skills in ASL for effective communication at the elementary level. Students gain understanding of basic cross-cultural perspectives. Special Note: Course conducted in American Sign Language. Attributes: UAA Humanities GER. ASL A102 Elementary American Sign Language II 4 Credits Continuation of introductory course. Further develops elementary receptive and expressive signing skills in American Sign Language for effective communication. Enhances appreciation of cross-cultural perspectives. Special Note: Course conducted in American Sign Language. Prerequisites: ASL A101 with a minimum grade of C. Attributes: UAA Humanities GER. ASL A201 Intermediate American Sign Language I 4 Credits Intermediate course for students with basic knowledge of American Sign Language. Enhances receptive and expressive signing skills for effective communication at the intermediate level. Students critically examine diverse cultural perspectives. Special Note: Course conducted in American Sign Language. Prerequisites: ASL A102 with a minimum grade of C. Attributes: UAA Humanities GER. ASL A202 Intermediate American Sign Language II 4 Credits Continuation of first semester in intermediate American Sign Language (ASL). Further develops receptive and expressive signing proficiency for effective communication and in preparation for advanced study of ASL. Students interpret diverse cultural perspectives. Special Note: Course conducted in American Sign Language. Prerequisites: ASL A201 with a minimum grade of C. Attributes: UAA Humanities GER.. -

Access to Assessments

GUIDANCE FOR AWARDING BODIES Access to External Assessment for D/deaf Candidates Version 3 – December 2006 1 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 4 2. About the D/deaf Candidate 5 3. Making Reasonable Adjustments 7 4. Range of Reasonable Adjustments to the Assessment of D/deaf Candidates 8 A Changes to assessment conditions 8 A1 Extra time A2 Accommodation A3 Early opening of papers B Use of mechanical, electronic and technological aids 9 B1 Assistive technology B2 BSL/English dictionaries/glossaries C Modification to the presentation of assessment material 10 C1 Language modified assessment material a) Modified written paper b) Assessment material in British Sign Language C2 Modified or standard written paper with modification through ‘live’ presentation C3 Modified oral assessments a) Listening tests (language exam) and assessment material in audio format b) Listening tests (subjects other than languages) D Alternative ways of presenting responses 18 D1 Responses in British Sign Language to written questions D2 Responses in spoken English to written questions D3 Responses to oral assessments a) Speaking tests (language exam) b) Speaking/oral tests (subject exams other than languages) 2 E Use of access facilitators 20 E1 Reader E2 Scribe E3 Oral Language Modifier E4 BSL/English Interpreter E5 Transcriber E6 Lipspeakers, Note-takers, Speech to Text Reporters, Cued Speech Transliterators APPENDIX Summary of Reasonable Adjustments for D/deaf Candidates 31 Signature would like to thank everyone who contributed to this guidance, including members of the British Association of Teachers of the Deaf (BATOD), teachers of D/deaf students and other specialist staff at specific schools, colleges and universities. -

American Sign Language 1

1 American Sign Language 1 PST 301-OL1 term, three credits, date Instructor Information Name: Office Location: Online My office hours are: Course Information This course introduces the basics of American Sign Language (ASL). This course is designed for students with no or minimal sign language skills to develop basic skills in use of ASL and knowledge of Deaf culture. Emphasis is upon acquisition of comprehension, production and interactional skills using basic grammatical features. ASL will be taught within contexts and related to general surroundings and everyday life experiences. ASL2 Programs Mission Statement Gallaudet University’s ASL2 Program is dedicated to providing an exemplary array of comprehensive and interactive curricula for individuals interested in learning American Sign Language (ASL) as a second language or foreign language. Using direct instruction and immersion in ASL, augmented by written English and visual learning supports, the program’s instructors engage learners in acquiring and developing increasing levels of proficiency in expressive and receptive use of the language. They also guide student’s exploration of the development of the language, its complexities and relevance in American Deaf communities. Syllabus, Course, Instructor, Term 2 Gallaudet University Student Outcomes Gallaudet University’s Student Learning Outcomes are: 1. Language and Communication - Students will use American Sign Language (ASL) and written English to communicate effectively with diverse audiences, for a variety of purposes, and in a variety of settings. 2. Critical Thinking - Students will summarize, synthesize, and critically analyze ideas from multiple sources in order to draw well-supported conclusions and solve problems. 3. Identity and Culture - Students will understand themselves, complex social identities, including deaf identities, and the interrelations within and among diverse cultures and groups. -

400 Years of Change In

Digiti lingua: a celebration of British Sign Language and Deaf Culture Bencie Woll Deafness Cognition and Language Research Centre UCL 1 Structure of this talk • Introduction to BSL: its history and social context • Historical sources • What kind of language is BSL? • Change in BSL • BSL in the future Introduction to BSL: its history and social context Some myths about sign language • There is one universal sign language • Sign language consists of iconic gestures • Sign languages were invented by hearing people to help deaf people • Sign languages have no grammar • BSL is just English on the hands Truths about sign language • There are many different sign languages in the world • Sign languages are just as conventionalised as spoken languages • Sign languages are natural languages, the creation of deaf communities • Sign languages have their own complex grammars BSL – language of the British Deaf community • An estimated 50,000-70,000 sign language people • Forms a single language group with Australian and New Zealand sign languages • Unrelated to American Sign Language or Irish Sign Language Social context of BSL • A minority language used by a community with historically low status • Non-traditional transmission patterns • Extensive regional lexical variation • A bilingual community, but with variable access to the language of the majority • Has experienced active attempts at suppression over many centuries Home sign • Gestural communication systems developed during communication between deaf children and hearing adults • Unlike sign -

American Sign Language

• HOME • INFORMATION & REFERRAL • AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE American Sign Language • What is American Sign Language? • Five (5) common misconceptions people have about ASL • Where can I take sign language (ASL) classes in Rhode Island? • Where can I find additional information about ASL? • For Parents: Where can I find information and resources for my deaf child? What Is American Sign Language (ASL)? ASL, short for American Sign Language, is the sign language most commonly used by the Deaf and Hard of Hearing people in the United States. Approximately more than a half-million people throughout the US (1) use ASL to communicate as their native language. ASL is the third most commonly used language in the United States, after English and Spanish. Contrary to popular belief, ASL is not representative of English nor is it some sort of imitation of spoken English that we use on a day-to-day basis. For many, it will come as a great surprise that ASL has more similarities to spoken Japanese and Navajo than to English. When we discuss ASL, or any other type of sign language, we are referring to what is called a visual-gestural language. The visual component refers to the use of body movements versus sound. Because “listeners” must use their eyes to “receive” the information, this language was specifically created to be easily recognized by the eyes. The “gestural” component refers to the body movements or “signs” that are performed to convey a message. A Brief History of ASL ASL is a relatively new language, which first appeared in the 1800s’ with the founding of the first successful American School for the Deaf by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc (first Deaf Teacher from France) in 1817. -

Chapter 2 Sign Language Types

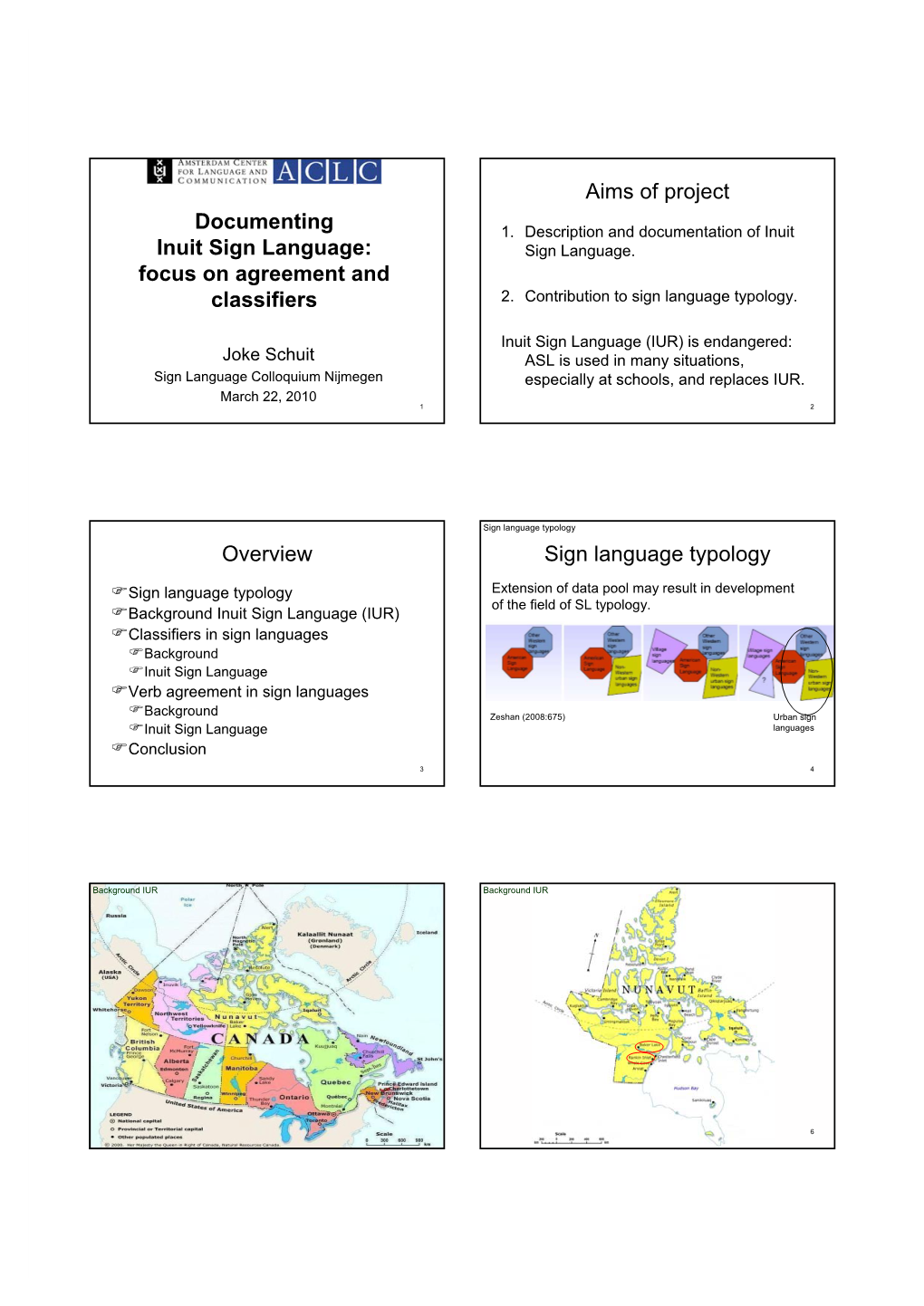

Chapter 2 Sign language types This chapter defines four different sign language types, based on the infor- mation available in the respective sources. Before introducing the types of sign languages, I first report on the diachronic developments in the field of typological sign language research that gave rise to the distinction of the various sign language types. Sign language research started about five decades ago in the United States of America mainly due to the pioneering work of Stokoe (2005 [1960]), Klima and Bellugi (1979), and Poizner, Klima and Bellugi (1987) on American Sign Language (ASL). Gradually linguists in other countries, mainly in Europe, became interested in sign language research and started analyzing European sign languages e.g. British Sign Language (BSL), Swedish Sign Language (SSL), Sign Language of the Netherlands (NGT) and German Sign Language (DGS). Most of the in-depth linguistic descrip- tions have been based on Western sign languages. Therefore, it has long been assumed that some fundamental levels of linguistic structure, such as spatial morphology and syntax, operate identically in all sign languages. Recent studies, however, have discovered some important variations in spatial organization in some previously unknown sign languages (Washabaugh, 1986; Nyst, 2007; Marsaja, 2008; Padden, Meir, Aronoff, & Sandler, 2010). In the context of growing interest in non-Western sign languages towards the end of the 1990s and more recently, there have been efforts towards developing a typology of sign languages (Zeshan, 2004ab, 2008, 2011b; Schuit, Baker, & Pfau, 2011). Although it has been repeatedly emphasized in the literature that the sign language research still has too little data on sign languages other than those of national deaf communities, based in Western or Asian cultures (Zeshan, 2008). -

Linguistic Access to Education for Deaf Pupils and Students in Scotland

BRITISH SIGN LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTIC ACCESS WORKING GROUP SCOPING STUDY: LINGUISTIC ACCESS TO EDUCATION FOR DEAF PUPILS AND STUDENTS IN SCOTLAND © Crown copyright 2009 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5849-8 (Web only) This document is also available on the Scottish Government website: www.scotland.gov.uk RR Donnelley B56660 02/09 www.scotland.gov.uk BRITISH SIGN LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTIC ACCESS WORKING GROUP SCOPING STUDY: LINGUISTIC ACCESS TO EDUCATION FOR DEAF PUPILS AND STUDENTS IN SCOTLAND The Scottish Government, Edinburgh 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are very grateful to the many individuals who have contributed their time and commitment to this study. Appendix 2 lists the main organisations who have taken part. The views expressed in this report are those of the researcher and do not necessarily represent those of the Scottish Government or Scottish officials. © Crown copyright 2009 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5849-8 (Web only) The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Government by RR Donnelley B56660 02/09 Published by the Scottish Government, February, 2009 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION (including glossary of abbreviations) 1 2. METHODS 4 I Statistical information I Qualitative information I Documentary information THE LINGUISTIC ACCESS CONTEXT FOR DEAF PUPILS AND STUDENTS IN SCOTLAND 3. LANGUAGE APPROACHES USED WITH DEAF PUPILS IN SCOTLAND 7 I Monolingual approaches I Bilingual approaches I ‘No specific policy’ I Regional variation 4. LINGUISTIC ACCESS FOR DEAF STUDENTS IN FURTHER AND HIGHER EDUCATION 11 THE SCHOOL SECTOR: LINGUISTIC ACCESS TO EDUCATION FOR DEAF PUPILS NUMBERS OF PUPILS AND PROFESSIONALS 5. THE NUMBER OF DEAF PUPILS 13 I Scottish Government Statistics I ADPS statistics I Presenting statistics on the population of deaf pupils I Statistics relating to educational attainment I Recommendations 6.