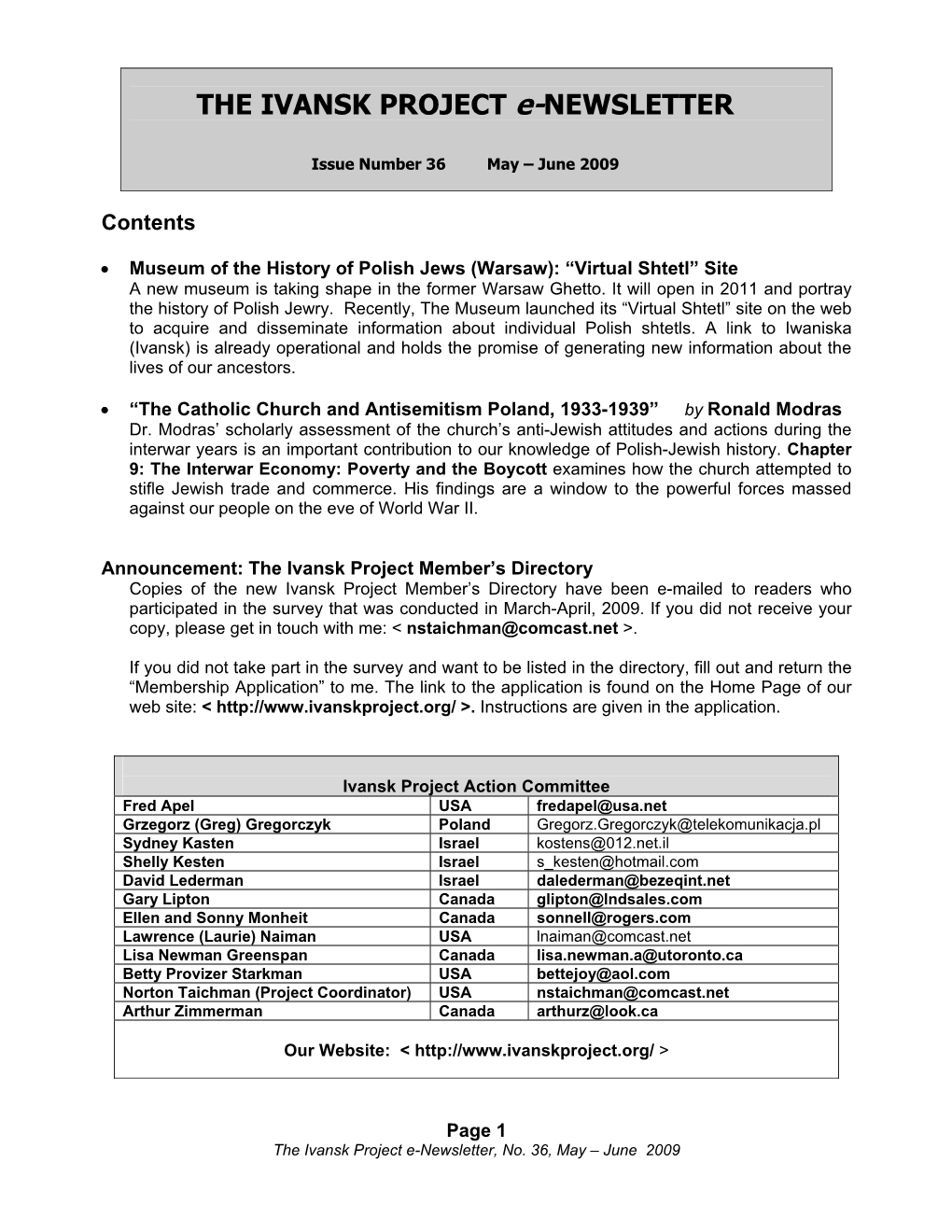

THE IVANSK PROJECT E-NEWSLETTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gazeta Fall/Winter 2018

The site of the Jewish cemetery in Głowno. Photograph from the project Currently Absent by Katarzyna Kopecka, Piotr Pawlak, and Jan Janiak. Used with permission. Volume 25, No. 4 Gazeta Fall/Winter 2018 A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Adam Schorin, Maayan Stanton, Agnieszka Ilwicka, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design. CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 2 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 3 FEATURES The Minhag Project: A Digital Archive of Jewish Customs Nathaniel Deutsch ................................................................................................................. 4 Teaching Space and Place in Holocaust Courses with Digital Tools Rachel Deblinger ................................................................................................................... 7 Medicinal Plants of Płaszów Jason Francisco .................................................................................................................. 10 REPORTS Independence March Held in Warsaw Amid Controversy Adam Schorin ...................................................................................................................... 14 Explaining Poland to the World: Notes from Poland Daniel Tilles -

Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich Polin Raport Roczny

MUZEUM HISTORII ŻYDÓW POLSKICH POLIN RAPORT ROCZNY POLIN MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF POLISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 polin.pl 1 2 Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Wspólna instytucja kultury / Joint Institution of Culture MUZEUM HISTORII ŻYDÓW POLSKICH POLIN RAPORT ROCZNY POLIN MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF POLISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Wydawca / Publisher: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN / POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews ISBN: 978-83-957601-0-5 Warszawa 2020 Redakcja / editor: Dział Komunikacji Muzeum POLIN / Communications Department, POLIN Museum Projekt graficzny, skład i przygotowanie do druku / Layout, typesetting: Piotr Matosek Tłumaczenie / English translation: Zofia Sochańska Korekta wersji polskiej / proofreading of the Polish version: Tamara Łozińska Fotografie / Photography: Muzeum POLIN / Photos: POLIN Museum 6 Spis treści / Table of content Muzeum, które zaciekawia ludzi... innymi ludźmi / Museum which attracts people with… other people 8 W oczekiwaniu na nowy rozdział / A new chapter is about to begin 10 Jestem w muzeum, bo... / I have came to the Museum because... 12 Wystawa stała / Core exhibition 14 Wystawy czasowe / Temporary exhibitions 18 Kolekcja / The collection 24 Edukacja / Education 30 Akcja Żonkile / The Daffodils campaign 40 Działalność kulturalna / Cultural activities 44 Scena muzyczna / POLIN Music Scene 52 Do muzeum z dziećmi / Children at the Museum 60 Żydowskość od kuchni / In the Jewish kitchen and beyond 64 Muzeum online / On-line Museum 68 POLIN w terenie / POLIN en route 72 Działalność naukowa / Academic activity 76 Nagroda POLIN / POLIN Award 80 Darczyńcy / Donors 84 Zespół Muzeum i wolontariusze / Museum team and volunteers 88 Muzeum partnerstwa / Museum of partnership 92 Bądźmy w kontakcie! / Let us stay in touch! 94 7 Muzeum, które zaciekawia ludzi.. -

Two Awards for POLIN Museum in the SY- BILLA Competition

Two Awards for POLIN Museum in the SY- BILLA Competition The Warsaw Ghetto Museum would like to congratulate the Virtual Shtetl portal and POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. The Museum received two awards in the SYBILLA competition for the Museum Event of the Year – honouring the achievements of Polish museology and organized by The National Institute for Museums and Public Collections – for the Virtual Shtetl portal and for the social and educational Daffodils Campaign and the Łączy Nas Pamięć [The Memory Connects Us] concert implemented as part of the 75th anniversary of the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. This year, prizes were awarded in six categories and the Grand Prix, which was received by the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław for the temporary exhibition of Leon Tarasewicz. This is a change compared to the last editions, when 11 prizes were awarded. The aim of the SYBILLA competition is to award people and institutions praiseworthy for their care and protection of Polish cultural heritage. On this occasion, we are talking to Mr Albert Stankowski, Director of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum and originator and the first coordinator of the honoured portal about its origins, the potential inherent in voluntary service and the growing interest in the culture and history of Polish Jews. What was the knowledge of the Jewish history of our – once – neighbours in 2009, when you were creating the Virtual Shtetl? First of all, I would like to congratulate POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews for the award received for the Virtual Shtetl portal in the SYBILLA Competition for the Museum Event of the Year. -

Jewish Ghettos in Europe

Jewish ghettos in Europe Jewish ghettos in Europe were neighborhoods of European cities in which Jews were permitted to live. In addition to being confined to the ghettos, Jews were placed under strict regulations as well as restrictions in many European cities.[1] The character of ghettos varied over the centuries. In some cases, they comprised aJewish quarter, the area of a city traditionally inhabited by Jews. In many instances, ghettos were places of terrible poverty and during periods of population growth, ghettos had narrow streets and small, crowded houses. Residents had their own justice system. Around the ghetto stood walls that, during pogroms, were closed from inside to protect the community, but from the outside during Christmas, Pesach, and Easter Week to prevent the Jews from leaving at those times. In the 19th century, Jewish ghettos were progressively abolished, and their walls taken down. However, in the course of World War II the Third Reich created a totally new Jewish ghetto-system for the purpose of persecution, terror, and exploitation of Jews, mostly in Eastern Europe. According to USHMM archives, "The Germans established at least 1,000 ghettos inGerman-occupied and annexed Poland and the Soviet Union alone."[2] Contents Ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust Jewish ghettos in Europe by country Austria The distribution of the Jews in Central Europe (1881, Soviet Belarus German). Percentage of local population: Croatia 13–18% Dubrovnik Split 9–13% Czech Republic 4–9% France 3–4% Germany 2–3% Frankfurt Friedberg 1–2% The Third Reich and World War II 0.3–1% Hungary 0.1–0.3% Italy < 0.1% Mantua Piedmont Papal States Venice Sicily Southern Italy Lithuania Poland The Holocaust in German-occupied Poland Spain The Netherlands Turkey United Kingdom References Ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust During World War II, the new category of Nazi ghettos was formed by the Third Reich in order to confine Jews into tightly packed areas of the cities of Eastern and Central Europe. -

Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland During World War II1

July 2008 Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II1 Mark Paul Collaboration with the Germans in occupied Poland is a topic that has not been adequately explored by historians.2 Holocaust literature has dwelled almost exclusively on the conduct of Poles toward Jews and has often arrived at sweeping and unjustified conclusions. At the same time, with a few notable exceptions such as Isaiah Trunk3 and Raul Hilberg,4 whose findings confirmed what Hannah Arendt had written about 1 This is a much expanded work in progress which builds on a brief overview that appeared in the collective work The Story of Two Shtetls, Brańsk and Ejszyszki: An Overview of Polish-Jewish Relations in Northeastern Poland during World War II (Toronto and Chicago: The Polish Educational Foundation in North America, 1998), Part Two, 231–40. The examples cited are far from exhaustive and represent only a selection of documentary sources in the author’s possession. 2 Tadeusz Piotrowski has done some pioneering work in this area in his Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces, and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998). Chapters 3 and 4 of this important study deal with Jewish and Polish collaboration respectively. Piotrowski’s methodology, which looks at the behaviour of the various nationalities inhabiting interwar Poland, rather than focusing on just one of them of the isolation, provides context that is sorely lacking in other works. For an earlier treatment see Richard C. Lukas, The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation, 1939–1944 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986), chapter 4. -

“Jewish Life: Diversity and Experience” Teacher's

Pre-Virtual Experience Activity “Jewish Life: Diversity and Experience” Teacher’s Guide Time Needed: 1-3 hours Teacher Note: Many of the resources for this activity are located on the IWitness website. Please register at http://iwitness.usc.edu and create your free account in order to access the resources. Introduction: The area that is now Poland had, on the eve of World War II, been home to Jewish communities for over 800 years. The genocide of European Jewry carried out by the German Nazis and their collaborators occurred under the cover of the Second World War across Europe. The events were complex, multilayered, occurred over a period of years, and were interlinked with the military events of the Second World War. As a result, it is not possible to present a simple lesson that addresses this complexity. The focus of this Virtual Experience is on a visit to Poland. Unlike Germany, where it is possible to trace gradual legalized antisemitic actions carried out by the Nazi regime, legislation in Poland happened overnight when the Nazis invaded and conquered the country in September 1939. The focus of this activity is Poland. However, it is important that students understand the diversity of European Jewry, and it is recommended they spend time reading the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum article (see Part I Resources), as well as viewing testimony. It should also be remembered that of the 3.3 million Jews in Poland before the Second World War only 45,000 remained, therefore the stories we have of the experience of genocide come from a surviving minority. -

The Function of Memory from the Warsaw Ghetto As Presented by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2021 The Function of Memory from the Warsaw Ghetto as Presented by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Hannah M. Labovitz Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Labovitz, Hannah M., "The Function of Memory from the Warsaw Ghetto as Presented by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews" (2021). Student Publications. 913. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/913 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Function of Memory from the Warsaw Ghetto as Presented by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Abstract Because of the extreme challenges they endured within Warsaw Ghetto and the slim chance they had at survival, the Jewish people sought to protect their legacy and leave a lasting impact on the world. They did so by both documenting their experiences, preserving them in what was known as the Oyneg Shabes archives, and by engaging in a bold act of defiance against the Nazis with the arsawW Ghetto Uprising in 1943, rewriting the narrative of Jewish passivity. With both instances, the POLIN Museum presents these moments of the past and shapes a collective memory based on a Jewish perspective with which the public can engage. -

IAJGS 2018 Handout Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Meet the Family: A Journey of a Thousand Years at POLIN Museum The JGSLA - Pamela Weisberger Memorial Lecture Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Chief Curator, Core Exhibition POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews [email protected] Monday August 6, 2018, 6:00-7:30 PM 2018 IAJGS Conference, Warsaw Marriott Hotel POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Warsaw) POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews http://www.polin.pl/en POLIN Museum core exhibition walkthrough https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSry8ilrMmY POLIN Museum core exhibition self-guided thematic tours: Highlights, Women, Religious Life, Yiddish (download PDF or view online) http://virtualtour.polin.pl/ POLIN Museum Resource Center http://www.polin.pl/en/resource-center Virtual Shtetl https://sztetl.org.pl/en/ Aheym: The Archives of Historical and Ethnographic Yiddish Memories http://www.iub.edu/~aheym/index.php Jewish Historical Institute (Warsaw) http://www.jhi.pl/en Portal Delet (download the app) http://www.jhi.pl/en/blog/2018-07-17-the-delet-app-is-available Jewish Historical Institute Genealogy Department http://www.jhi.pl/en/genealogy Cemeteries and Synagogues Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland http://cemetery.jewish.org.pl/lang_en/ 1 Database of tombstones in the Jewish cemetery on Okopowa in Warsaw http://cemetery.jewish.org.pl/list/c_1 Guide to the tombstones designed by Abraham Ostrzega in the Warsaw Jewish cemetery on Okopowa https://zacheta.art.pl/public/upload/mediateka/pdf/59242d3961058.pdf Additional information http://www.polishhistory.pl/index.php?id=17&L=1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=4524&tx_ttne -

Wall and Window. the Rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto As the Narrative

Wall and Window The rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto as the narrative space of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews* Konrad Matyjaszek Abstract: Opened in 2013, the Warsaw-based POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews is situated in the center of the former Nazi Warsaw ghetto, which was destroyed during its liquidation in 1943. The museum is also located opposite to the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes and Martyrs, built in 1948, as well as in between of the area of the former 19th-century Jewish district, and of the post-war modernist residential district of Mu- ranów, designed as a district-memorial for the destroyed ghetto. Constructed on such site, the Museum was however narrated as a “museum of life”, telling the “thousand-year-old history” of Polish Jews, and not focused directly on the history of the Holocaust or the history of Polish antisemitism. The paper offers a critical analysis of the curatorial and architectural strategies assumed by the Museum’s de- signers in the process of employing the urban location of the Museum in the narratives communicated by the building and its core exhibition. In this analysis, two key architectural interiors are examined in detail in terms of their correspondence with the context of the site: the Museum’s entrance lobby and the space of the “Jewish street,” incorporated into the core exhibition’s sub-galleries presenting the interwar period of Polish-Jewish history and the history of the Holocaust. The analysis of the design structure of these two interiors allows to raise the research question about the physical and symbolic role of the material substance of the destroyed ghetto in construction of a historical narrative that is separated from the history of the destruction, as well as one about the designers’ responsibilities arising from the decision to present a given history on the physical site where it took place. -

SUGGESTED RESOURCES for TEACHERS and STUDENTS for Grades 7 – 12

SUGGESTED RESOURCES for TEACHERS and STUDENTS For Grades 7 – 12 Compiled by Josey G. Fisher, Holocaust Education Consultant Recommended for teachers and students participating in the MORDECHAI ANIELEWICZ CREATIVE ARTS COMPETITION Contents I. Jewish Life in Pre-War Europe page 3 II. The World at War page 4 III. Life and Resistance in the Ghetto page 6 IV. Life and Resistance in the Concentration Camp page 9 V. Cultural Resistance: Art, Music, Poetry and Education page 11 VI. The Experiences of Children page 13 VII. Are You Your Brother’s Keeper? page 15 VIII. Communities of Conscience: Rescue and Resistance page 18 IX. The World Watched in Silence page 19 X. Liberation and Its Aftermath page 20 * * * * * * * Recommended websites for historical background, primary resources, and classroom materials: 1. Echoes and Reflections http://echoesandreflections.org 2. Facing History and Ourselves -- https://www.facinghistory.org/ 3. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team: http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/toc.html 4. Jewish Virtual Library – The Holocaust -- http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-holocaust 5. Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation: http://jewishpartisans.org/ 6. A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust (University of South Florida) -- http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/holocaust/sitemap/sitemap.htm 7. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – https://www.ushmm.org 8. USC Shoah Foundation -- https://sfi.usc.edu/ 9. Yad Vashem – www.yadvashem.org * May be considered for 7th - 8th grades 2 I. JEWISH LIFE IN PRE-WAR EUROPE A. Websites: 1. Baral Family Holocaust Memorial Website: From a Vanished World -- http://baral.com/ 2. Centropa -- http://www.centropa.org/ -- See “Exhibitions” 3. Museum of Tolerance Online Multimedia Learning Center - "And I Still See Their Faces” -- http://motlc.wiesenthal.com/ -- Click on "Virtual Exhibits" 4. -

Reflections. AJC Annual Alumni Journal 2016

OVERVIEW ABOUT THE AUSCHWITZ JEWISH CENTER Established in 2000, the Auschwitz Jewish Center (AJC), a partner of the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, is a cultural and educational institution located in Oświęcim, Poland. Located less than two miles from Auschwitz-Birkenau, the AJC strives to juxtapose the enormity of the destruction of human life with the vibrant lives of the Jewish people who once lived in the adjacent town and throughout Poland. The AJC’s mission is also to provide all visitors with an opportunity to memorialize victims of the Holocaust through the study of the life and culture of a formerly Jewish town and to offer educational programs that allow new generations to explore the meaning and contemporary implications of the Holocaust. The AJC—including a museum, education center, synagogue, and café—is a place of understanding, education, memory, and prayer for all people. In addition to on-site educational offerings, the AJC offers international academic opportunities including the American Service Academies Program, Fellows Program, Program for Students Abroad, Human Rights Summer Program, and Customized Programs throughout the year. REFLECTIONS | 2016 AUSCHWITZ JEWISH CENTER ANNUAL ALUMNI JOURNAL ABOUT REFLECTIONS Reflections is an annual academic journal of selected pieces by AJC program alumni. Its aim is to capture the perspectives, experiences, and interests of that year’s participants. The AJC Newsletter, published three times per year, provides snapshots of the Center’s work; Reflections is an in-depth supplement that will be published at the end of each year. The following are authored by alumni of the following programs: The American Service Academies Program (ASAP) is a two-week educational initiative for a select group of cadets and midshipmen from the U.S. -

EXTRA! EXTRA! EXTRA! Yiddish Survives the Millennium!

January2000 Vol 10 No.1 EXTRA! EXTRA! EXTRA! Yiddish Survives the Millennium! Despite the vocalized nay-sayers of academia, our beloved mame-los-hn is thriving. There is a slight resurgence in Israel, the former USSR and even in the United States. There are an increasing number of colleges with Yiddish courses. There is the growth of the National Yiddish Book Center, and the increase of Yiddish conferences, institutes and festivals. We have the founding of our International Association of Yiddish Clubs, and the increase in Klezmer groups. All of this doesn't take into account the vast usage of Yiddish among the Haredi. Yiddish is alive and well!! One of the major reasons for the continued interest in Yiddish in outlying areas is the wonderful ability to communicate over the World Wide Web. Mendele, the #1 Yiddish list online, has over-2,000 members all over-the world. Having access to the highest levels of academia and being:able to ask questions makes this the true frontier-of Yiddish world-wide. Several Yiddishists stand out in the forefront of this Yiddish, cyberspace revolution. Notable among this young:group are; Iosif Vaisman, the primary moderator of the Mendele List, Mark David, who mns the-UYIP, and Rafoyel Finkel, whose web site is one of the very best. To this list must be added the wonderful work of the Paris-based newsletters and web site -truly gems. Der Bay is an acronym for Bay Area Yiddish, and starts its 10th year of continuous publication. Its growth in numbers and services are totally due to your support.