Blf4c,AP Icau NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Greek Culture Representation in Socio-Economic Development of the Southern Regions of Russia

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXI, Special Issue 1, 2018 pp. 136 - 147 The Role of Greek Culture Representation in Socio-Economic Development of the Southern Regions of Russia T.V. Evsyukova1, I.G. Barabanova2, O.V. Glukhova3, E.A. Cherednikova4 Abstract: This article researches how the Greek lingvoculture represented in onomasticon of the South of Russia. The South Russian anthroponyms, toponyms and pragmatonyms are considered in this article and how they verbalize the most important values and ideological views. It is proved in the article that the key concepts of the Greek lingvoculture such as: “Peace”, “Faith”, “Love”, “Heroism”, “Knowledge”, “Alphabet”, “Power”, “Charismatic person” and “Craft” are highly concentrated in the onomastic lexis of the researched region. The mentioned above concepts due to their specific pragmatic orientation are represented at different extend. Keywords: Culture, linguoculture, onomastics, concept anthroponym, toponym, pragmatonim. 1D.Sc. in Linguistics, Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. 2Ph.D. in Linguistics, Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. 3Lecturer, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation, E-mail: [email protected] 4Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. T.V. Evsyukova, I.G. Barabanova, O.V. Glukhova, E.A. Cherednikova 137 1. Introduction There is unlikely to be any other culture that influenced so much on the formation of other European cultures, as the Greek culture. -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law

The North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law Europe Report N°226 | 6 September 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Russia between Decentralisation and the “Vertical of Power” ....................................... 3 A. Federative Relations Today ....................................................................................... 4 B. Local Government ...................................................................................................... 6 C. Funding and budgets ................................................................................................. 6 III. Elections ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. State Duma Elections 2011 ........................................................................................ 9 B. Presidential Elections 2012 ...................................................................................... -

Chapter V Specifics of Sustainable Rural Development in Resort Areas: Case of Caucasus Mineral Waters

CHAPTER V SPECIFICS OF SUSTAINABLE RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN RESORT AREAS: CASE OF CAUCASUS MINERAL WATERS Anna IVOLGA, Alexander TRUKHACHEV ABSTRACT The chapter aims at overview of issued, related to specifics of sustain- able rural development in resort areas. There is the analysis of dynamics and current state of tourism and recreation sector of Stavropol Region of the Russian Federation and particularly the resort area of Caucasus Miner- al Waters. The chapter describes the recreational, resort and agricultural potential of the region, as well as discovers the major problems of its effec- tive utilization in the purposes of sustainable rural development. The central objective of this chapter is to present a review of how tourism and recre- ation may affect rural development, as well as to provide a critical analysis of main approaches to sustainable regional development by means of tour- ism. The paper points out that tourism should get more attention in respect of sustainable development of rural territories and recreational areas, and the expected benefits from tourism must be carefully assessed. KEY WORDS: resorts, sustainable development, recreation, rural ter- ritories INTRODUCTION In recent years, the role of tourism has become more recognized in the con- text of the sustainable regional development, which includes use of natural re- sources and the sector’s potential contribution to the economic growth of the region. The practice of tourism has the potential to assist in conserving natural areas, alleviating poverty in rural territories, empowering women, enhancing education, and improving the health and well being of local communities. But how tourism can assist in supporting and meeting these potential goals? Relevance of sustainable economic development of the certain region is in the necessity to create the conditions for sustainable development of economic sector and raise of living standards of rural people by means of the effective usage of the existing sanatorium, resort, touristic and recreational potential. -

BYRONISM in LERMONTOV's a HERO of OUR TIME by ALAN HARWOOD CAMERON B.A., U N I V E R S I T Y O F C a L G a R Y , 1968 M.A

BYRONISM IN LERMONTOV'S A HERO OF OUR TIME by ALAN HARWOOD CAMERON B.A., University of Calgary, 1968 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department SLAVONIC STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1974 In presenting this thesis in par ial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date Afr, I l0} I f7f ABSTRACT Although Mikhail Lermontov is commonly known as the "Russian Byron," up to this point no examination of the Byronic features of A Hero of Our Time, (Geroy nashego vremeni)3 has been made. This study presents the view that, while the novel is much more than a simple expression of Byronism, understanding the basic Byronic traits and Lermontov1s own modification of them is essential for a true comprehension of the novel. Each of the first five chapters is devoted to a scrutiny of the separate tales that make up A Hero of Our Time. The basic Byronic motifs of storms, poses and exotic settings are examined in each part with commentary on some Lermontovian variations on them. -

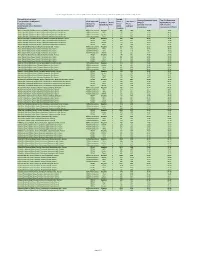

Appendix 2: Q4 (Oct-Dec) 2020 Cities in Russia Top Mobile Internet Providers Based on Average Download and Top 10% Speeds of Speedtest Intelligence Data

Appendix 2: Q4 (Oct-Dec) 2020 Cities in Russia Top Mobile Internet Providers based on average download and top 10% speeds of Speedtest Intelligence data City and Location Name Sample Average Download Speed Top 10% Download from Speedtest Intelligence / Claim Approved CoUnt / Test CoUnt / Provider / Rank / (Mbps) / Speed (Mbps) / Топ Название города, /Заявление Число Число Провайдер Ранг Средняя скорость 10% скорость местоположения из Speedtest одобрено точек замеров скачивания скачивания (Мбит/с) Intelligence замеров Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия All/Все технологии MegaFon 1 468 1369 34.89 79.85 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия All/Все технологии MTS 2 227 612 23.35 48.91 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия All/Все технологии Beeline 3 125 516 18.92 34.17 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия All/Все технологии Tele2 4 204 571 18.60 41.73 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия LTE/4G MegaFon 1 439 1257 35.61 79.35 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия LTE/4G MTS 2 205 491 24.35 49.98 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия LTE/4G Beeline 3 113 430 20.07 34.29 Abakan, Republic of Khakassia, Russia / Абакан, Республика Хакасия, Россия LTE/4G Tele2 4 192 527 19.17 43.24 AksaY, Rostov Oblast, Russia / Аксай, Ростовская обл., Россия All/Все технологии MegaFon 1 207 417 28.17 -

DMACC/Stavropol State Pedigogical Institute Reciprocal Visits

DMACC PIONEERS HISTORY PROJECT DMACC/SSPI RECIPROCAL VISITS DES MOINES AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND STAVROPOL STATE PEDIGOGICAL INSTITUTE AUTHOR CARROLL BENNETT CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS JOHN LIEPA ANN SCHODDE BURGESS SHRIVER FRANK TRUMPY 2019 DMACC travelers to Russia in May 1992 along with three SSPI employees Red Square, Moscow Front Row: Evgeni Popomarev, Gary Stasko, Slava Strugov, John Liepa, Frank Trumpy, Joe Harper, Ewa Pratt (standing) Back Row: Mark Pogge, Vivian Brandmeyer, Carroll Bennett, Anne Schulte, Alexi Erokhin, Ann Schodde, Peg Cutlip, Joe Robbins, Kim Linduska, Peggy Gaines, Burgess Shriver ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The rather extensive documentation and history of the DMACC/SSPI Exchange would not have progressed to the current level without the foresight and leadership of Carroll Bennett. Carroll initiated the meetings of our Steering Committee and provided the direction and motivation to write down and preserve these materials. He was the primary author and our editor-in-chief. Sadly, Carroll died on June 11, 2019, just prior to the completion of this project. We want to pay tribute to Carroll for a very long devotion to DMACC and for his efforts to always do the right thing. We would like to further acknowledge Carroll’s grandson, Andrew Bennett, for perusing Carroll’s personal computer to find the dozens of DMACC/SSPI files and scans that were present. Andrew found everything we needed to reach closure on the project and forwarded it to us. Without his help, we would not been able to finish. When word of Carroll’s death reached Stavropol, Russia, this is what our very good friend Boris Zhogin wrote back: “I'd like to share with you one episode associated with dear Carroll that I feel and see very vividly. -

SGGEE Russia Gazetteer 201908.Xlsx

SGGEE Russia gazetteer © 2019 Dr. Frank Stewner Page 1 of 25 27.08.2021 Menno Location according to the SGGEE guideline of October 2013 North East Village name old Village name today Abdulino (Abdulino), Abdulino, Orenburg, Russia 534125 533900 Абдулино Абдулино Abramfeld (NE in Malchevsko-Polnenskaya), Millerovo, Rostov, Russia 485951 401259 Абрамфельд Мальчевско-Полненская m Abrampolski II (lost), Davlekanovo, Bashkortostan, Russia 541256 545650 Aehrenfeld (Chakalovo), Krasny Kut, Saratov, Russia 504336 470306 Крацкое/Эренфельд Чкалово Aidarowa (Aidrowo), Pskov, Pskov, Russia 563510 300411 Айдарово Айдарово Akimowka (Akimovka), Krasnoshchyokovo, Altai Krai, Russia 513511 823519 Акимовка Акимовка Aksenowo (Aksenovo), Ust-Ishim, Omsk, Russia 574137 713030 Аксеново Аксеново Aktjubinski (Aktyubinski), Aznakayevo, Tatarstan, Russia 544855 524805 Актюбинский Актюбинский Aldan/Nesametny (Aldan), Aldan, Sakha, Russia 583637 1252250 Алдан/Незаметный Алдан Aleksanderhoeh/Aleksandrowka (Nalivnaya), Sovetsky, Saratov, Russia 511611 465220 Александерге/АлександровкаНаливная Aleksanderhoeh/Uralsk (Aleksanrovka), Sovetsky, Saratov, Russia 511558 465112 Александерге Александровка Aleksandertal (lost), Kamyshin, Volgograd, Russia 501952 452332 Александрталь Александровка m Aleksandrofeld/Masajewka (lost), Matveyev-Kurgan, Rostov, Russia 473408 390954 Александрофельд/Мазаевка - Aleksandro-Newskij (Aleksandro-Nevskiy), Andreyevsk, Omsk, Russia 540118 772405 Александро-Невский Александро-Невский Aleksandrotal (Nadezhdino), Koshki, Samara, Russia 540702 -

Outdoor Activity Harassed, Banned and Violently Attacked

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 26 July 2010 RUSSIA: Outdoor activity harassed, banned and violently attacked By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org>, and <br> Geraldine Fagan, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Outdoor public religious activity by Russian Jehovah's Witnesses, Hare Krishna devotees and Protestants has resulted in harassment by the police, repeated bans, and in one case a refusal to defend a Protestant meeting against violent attack involving stun grenades, Forum 18 News Service notes. The categories of activity targeted subdivide into very small groups of people sharing their beliefs with others in conversation in the street - normally Jehovah's Witnesses or occasionally Protestants - and outdoor public meetings or worship. By far the most common form of harassment takes place against pairs of Jehovah's Witnesses, and can involve unduly severe treatment of elderly or infirm people. Hare Krishna devotees in both Smolensk and Stavropol regions have experienced repeated banning of outdoor meetings, on grounds such as that they "inconvenience tourists on the way to the drinking fountains". Baptists in Rostov Region have experienced an attempted ban on a street library. Baptists in Tambov Region were banned from holding evangelistic concerts in a village, and when they were attacked with stun grenades by unknown people police did nothing to defend them. Visible public religious activity in Russia is increasingly resulting in harassment by police, Forum 18 News Service notes, in some cases from officers responsible for fighting extremism. -

List of Cities in Russia

Population Population Sr.No City/town Federal subject (2002 (2010 Census (preliminary)) Census) 001 Moscow Moscow 10,382,754 11,514,330 002 Saint Petersburg Saint Petersburg 4,661,219 4,848,742 003 Novosibirsk Novosibirsk Oblast 1,425,508 1,473,737 004 Yekaterinburg Sverdlovsk Oblast 1,293,537 1,350,136 005 Nizhny Novgorod Nizhny Novgorod Oblast 1,311,252 1,250,615 006 Samara Samara Oblast 1,157,880 1,164,896 007 Omsk Omsk Oblast 1,134,016 1,153,971 008 Kazan Republic of Tatarstan 1,105,289 1,143,546 009 Chelyabinsk Chelyabinsk Oblast 1,077,174 1,130,273 010 Rostov-on-Don Rostov Oblast 1,068,267 1,089,851 011 Ufa Republic of Bashkortostan 1,042,437 1,062,300 012 Volgograd Volgograd Oblast 1,011,417 1,021,244 013 Perm Perm Krai 1,001,653 991,530 014 Krasnoyarsk Krasnoyarsk Krai 909,341 973,891 015 Voronezh Voronezh Oblast 848,752 889,989 016 Saratov Saratov Oblast 873,055 837,831 017 Krasnodar Krasnodar Krai 646,175 744,933 018 Tolyatti Samara Oblast 702,879 719,514 019 Izhevsk Udmurt Republic 632,140 628,116 020 Ulyanovsk Ulyanovsk Oblast 635,947 613,793 021 Barnaul Altai Krai 600,749 612,091 022 Vladivostok Primorsky Krai 594,701 592,069 023 Yaroslavl Yaroslavl Oblast 613,088 591,486 024 Irkutsk Irkutsk Oblast 593,604 587,225 025 Tyumen Tyumen Oblast 510,719 581,758 026 Makhachkala Republic of Dagestan 462,412 577,990 027 Khabarovsk Khabarovsk Krai 583,072 577,668 028 Novokuznetsk Kemerovo Oblast 549,870 547,885 029 Orenburg Orenburg Oblast 549,361 544,987 030 Kemerovo Kemerovo Oblast 484,754 532,884 031 Ryazan Ryazan Oblast 521,560 -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (Ii), Islam, the Insurgency and Counter-Insurgency

THE NORTH CAUCASUS: THE CHALLENGES OF INTEGRATION (II), ISLAM, THE INSURGENCY AND COUNTER-INSURGENCY Europe Report N°221 – 19 October 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE ISLAMIC FACTOR AND ISLAMIST PROJECT .............................................. 3 A. THE SECTARIAN CONFLICT .......................................................................................................... 3 B. SALAFISM’S SPREAD AND RADICALISATION: INGUSHETIA AND KABARDINO-BALKARIA .............. 5 C. SALAFISM IN RELIGIOUSLY MIXED REPUBLICS ............................................................................ 6 D. DAGESTAN: SALAFIS, SUFIS AND DIALOGUE ................................................................................ 9 E. CHECHNYA: IDEOLOGICAL COMBAT AND ERADICATION ............................................................ 12 III. THE INSURGENCY ....................................................................................................... 13 A. THE CAUCASUS EMIRATE (IMARAT KAVKAZ) ............................................................................ 13 B. LEADERSHIP AND RECRUITMENT ............................................................................................... 14 C. TACTICS AND OPERATIONS ....................................................................................................... -

№ 2(26), 2017 Íàó×Íî- Ïðàêòè×Åñêèé Главный Редактор Ïîäêîëçèí Î

B № 2(26), 2017 ÍÀÓ×ÍÎ- ÏÐÀÊÒÈ×ÅÑÊÈÉ ГЛАВНЫЙ РЕДАКТОР Ïîäêîëçèí Î. À., äîêòîð ñåëüñêîõîçÿéñòâåííûõ íàóê, Òðóõà÷åâ Â. È., ïðîôåññîð (Ñòàâðîïîëü, Ðîññèéñêàÿ ÆÓÐÍÀË Ôåäåðàöèÿ) Èçäàåòñÿ ñ 2011 ãîäà, ðåêòîð ÔÃÁÎÓ ÂÎ Ðóäåíêî Í. Å., åæåêâàðòàëüíî. «Ñòàâðîïîëüñêèé äîêòîð òåõíè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð (Ñòàâðîïîëü, Ðîññèéñêàÿ Ôåäåðàöèÿ) ãîñóäàðñòâåííûé àãðàðíûé Ñîòíèêîâà Ë. Ô., Ó÷ðåäèòåëü: óíèâåðñèòåò», àêàäåìèê ÐÀÍ, äîêòîð âåòåðèíàðíûõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð ÔÃÁÎÓ ÂÎ «Ñòàâðîïîëüñêèé äîêòîð ñåëüñêîõîçÿéñòâåííûõ (Ìîñêâà, Ðîññèéñêàÿ Ôåäåðàöèÿ) Öõîâðåáîâ Â. Ñ., ãîñóäàðñòâåííûé àãðàðíûé óíèâåðñèòåò». íàóê, ïðîôåññîð, äîêòîð Òåððèòîðèÿ ðàñïðîñòðàíåíèÿ: ýêîíîìè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð, äîêòîð ñåëüñêîõîçÿéñòâåííûõ íàóê, Ðîññèéñêàÿ Ôåäåðàöèÿ, ïðîôåññîð (Ñòàâðîïîëü, Ðîññèéñêàÿ çàñëóæåííûé äåÿòåëü íàóêè Ôåäåðàöèÿ) çàðóáåæíûå ñòðàíû. Øóòêî À. Ï., Çàðåãèñòðèðîâàí â Ôåäåðàëüíîé ÐÔ (Ñòàâðîïîëü, Ðîññèéñêàÿ ñëóæáå ïî íàäçîðó â ñôåðå ñâÿçè Ôåäåðàöèÿ) äîêòîð ñåëüñêîõîçÿéñòâåííûõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð (Ñòàâðîïîëü, Ðîññèéñêàÿ èíôîðìàöèîííûõ òåõíîëîãèé РЕДАКЦИОННАЯ КОЛЛЕГИЯ: Ôåäåðàöèÿ) è ìàññîâûõ êîììóíèêàöèé Äðàãî Öâèÿíîâè÷, ÏÈ ¹ÔÑ77-44573 Áåëîâà Ë. Ì., äîêòîð ýêîíîìè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð îò 15 àïðåëÿ 2011 ãîäà. äîêòîð áèîëîãè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð (Âðíÿ÷êà Áàíÿ, Ñåðáèÿ) (Ñàíêò-Ïåòåðáóðã, Ðîññèéñêàÿ Ïèòåð Áèåëèê, Æóðíàë âêëþ÷åí â Ïåðå÷åíü Ôåäåðàöèÿ) äîêòîð òåõíè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð âåäóùèõ ðåöåíçèðóåìûõ íàó÷íûõ Áóí÷èêîâ Î. Í., (Íèòðà, Ñëîâàêèÿ) æóðíàëîâ è èçäàíèé, â êîòîðûõ äîêòîð ýêîíîìè÷åñêèõ íàóê, ïðîôåññîð Ìàðèÿ Ïàðëèíñêà, äîëæíû áûòü îïóáëèêîâàíû (Ðîñòîâ-íà-Äîíó, Ðîññèéñêàÿ -

Educational Innovation for the Ecological Assessment of the Effectiveness of Wildlife Management

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 46 ( 2012 ) 1284 – 1289 WCES 2012 Educational innovation for the ecological assessment of the effectiveness of wildlife management b Olga Perfilova a *, Yulia Alizade a Faculty of Ecology & Natural Sciences, Department of Ecology & Wildlife Management, Sholokhov Moscow State University for Humanities, Moscow , 109444, Russia b Faculty of Management, Department of Management & Integrated Marketing Communications, Russian State University of Innovation Technologies & Business, Moscow, 105058, Russia Abstract Research is devoted to solving complex aims: educational (the development of ecological competence of managers), and socio- economic (optimization of access to recreational resources) through the improvement of innovative algorithms, theory and practice of wildlife management. We also tried to identify the problems of integration of Natural and Human sciences as the problems of environmental education.This article contains a description of the elements of how to organize environmental management training in real situations. On the example of integrated assessment of the socio-natural potential (of the Caucasian Mineral Waters region) shows the role of competence in making optimal decisions that affect human values. The article emphasized that the possibility of society full of ecosystem services is directly linked to the idea of the uniqueness and intrinsic value of the natural world, whose safety should be regarded as a guarantee of human health. © 20122012 Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier Ltd. Ltd. Selection and/or peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Uzunboylu Keywords: innovation technologies; ecological competence; wildlife management; safety of ecological and social interaction; SWOT-analysis; recreational potential; health. Foreword This research is devoted to solving social problems and educational training of modern management, taking into account the immanent nature of the environmental specialist expertise in every field.