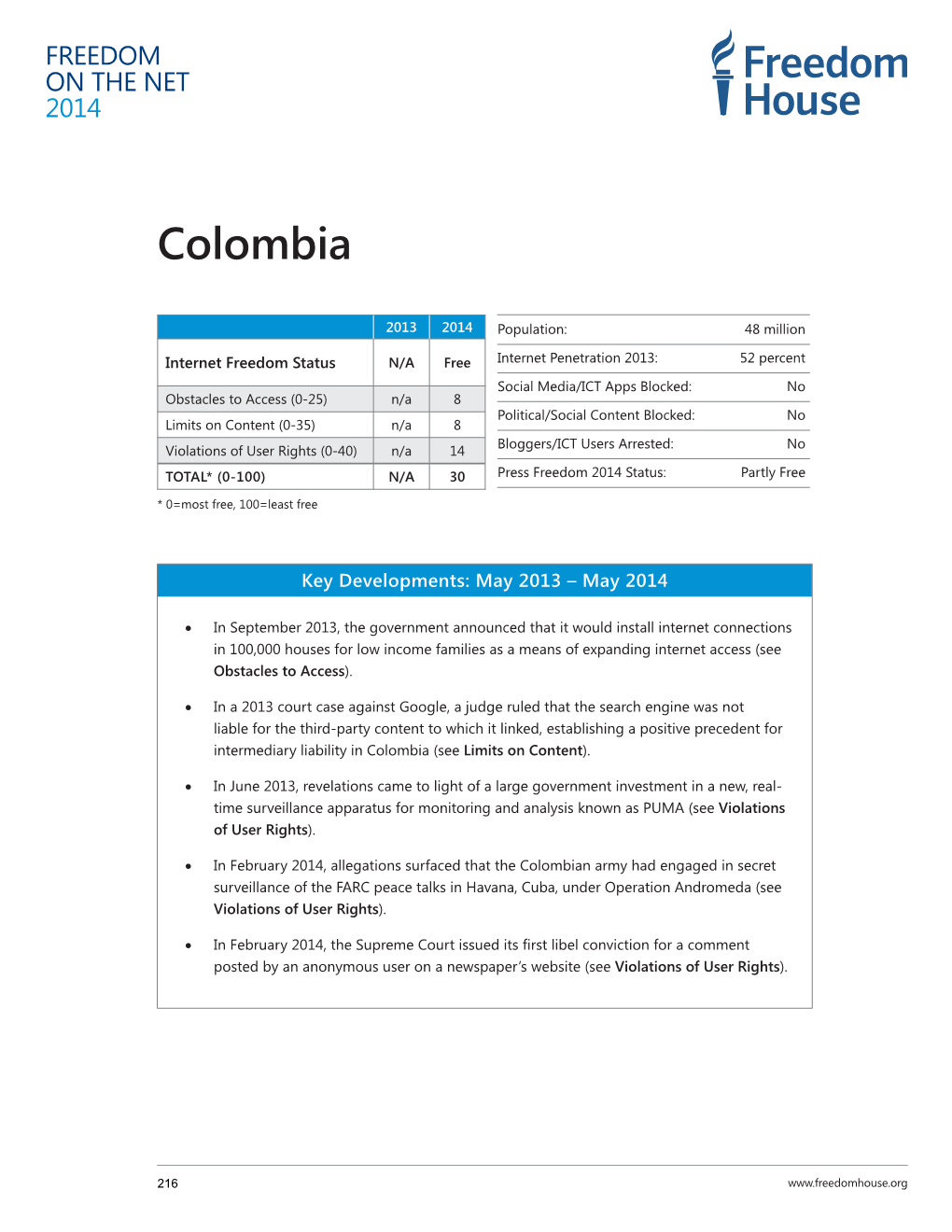

Freedom on the Net 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Environmental Crime in the Colombian Amazon

THE ROOTS OF ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME IN THE COLOMBIAN AMAZON IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE a think and do tank “Mapping environmental crime in the Amazon Basin”: Introduction to the series The “Mapping environmental crime in the markets, and the organizational characteristics Amazon Basin” case study series seeks to of crime groups and their collusion with understand the contemporary dynamics of government bodies. It also highlights the environmental crime in the Amazon Basin record of past and current measures to disrupt and generate policy recommendations for and dismantle criminal networks that have key-stakeholders involved in combating diversified into environmental crime across the environmental crime at the regional and Amazon Basin. domestic levels. The four studies further expose how licit and The Amazon Basin sprawls across eight illicit actors interact and fuel environmental countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, crime and degradation in a time of climate Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela) emergency as well as of accelerated socio- and one territory (French Guiana). While political change across the region. They show the research and policy communities a mix of increased governmental attention have progressively developed a sounding and action to combat environmental crime in understanding of deforestation and recent years, mainly to reduce deforestation degradation dynamics in the region and the and illegal mining, as well as the weakening of ways in which economic actors exploit forest environmental protections and land regulations, resources under different state authorisation in which political and economic elites are either regimes, this series sheds light on a less complicit in or oblivious to the destruction of explored dimension of the phenomenon: the the Amazon forest. -

The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime

PERSPECTIVAS 9/2014 The Changing Face of Colombian Organized Crime Jeremy McDermott ■ Colombian organized crime, that once ran, unchallenged, the world’s co- caine trade, today appears to be little more than a supplier to the Mexican cartels. Yet in the last ten years Colombian organized crime has undergone a profound metamorphosis. There are profound differences between the Medellin and Cali cartels and today’s BACRIM. ■ The diminishing returns in moving cocaine to the US and the Mexican domi- nation of this market have led to a rapid adaptation by Colombian groups that have diversified their criminal portfolios to make up the shortfall in cocaine earnings, and are exploiting new markets and diversifying routes to non-US destinations. The development of domestic consumption of co- caine and its derivatives in some Latin American countries has prompted Colombian organized crime to establish permanent presence and structures abroad. ■ This changes in the dynamics of organized crime in Colombia also changed the structure of the groups involved in it. Today the fundamental unit of the criminal networks that form the BACRIM is the “oficina de cobro”, usually a financially self-sufficient node, part of a network that functions like a franchise. In this new scenario, cooperation and negotiation are preferred to violence, which is bad for business. ■ Colombian organized crime has proven itself not only resilient but extremely quick to adapt to changing conditions. The likelihood is that Colombian organized crime will continue the diversification -

New Models for Universal Access to Telecommunications Services in Latin America

40829 NEW MODELS FOR UNIVERSAL ACCESS TO TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES Public Disclosure Authorized IN LATIN AMERICA PETER A. STERN, DAVID N. TOWNSEND FULL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK NEW MODELS FOR UNIVERSAL ACCESS TO TELECOMMUNICATIONS SERVICES IN LATIN AMERICA: LESSONS FROM THE PAST AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A NEW GENERATION OF UNIVERSAL ACCESS PROGRAMS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY FULL REPORT FORUM OF LATIN AMERICAN TELECOMMUNICATIONS REGULATORS Ceferino Alberto Namuncurá President, REGULATEL 2006-2007 Auditor, CNC Argentina ---------------------------------------- COMITE DE GESTION Ceferino Alberto Namuncurá Auditor, CNC Argentina Oscar Stuardo Chinchilla Superintendent, SIT Guatemala Héctor Guillermo Osuna Jaime President, COFETEL Mexico José Rafael Vargas President, INDOTEL, Secretary of State Dominican Republic Pedro Jaime Ziller Adviser, ANATEL Brazil Guillermo Thornberry Villarán President, OSIPTEL Peru -------------------------------- Gustavo Peña-Quiñones Secretary General All rights of publication of the report and related document in any language are reserved. No part of this report or related document can be reproduced, recorded or stored by any means or transmitted in any form or process, be it in electronic, mechanical, magnetic or any other form without the express, written permission obtained from the organizations who initiated and financed the study. The views and information presented in this report are the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views, opinions, conclusions of findings of the Forum of Latin American Telecommunications Regulators (Regulatel), the World Bank through its trust funds PPIAF and GPOBA, the European Commission and the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC). Table of Contents Executive Summary I. INTRODUCTION, p. 1 I.1 Background and objectives, p. -

Violence Against Women in Colombia

Organisation Mondiale Contre la Torture Case postale 21- 8, rue du Vieux Billard CH 1211 Genève 8, Suisse Tél. : 0041 22 809 49 39 – Fax : 0041 22 809 49 29 – E-mail : [email protected] Violence against Women in Colombia Report prepared by the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) for the 31st Session of Committee against Torture OMCT expresses its sincere gratitude to information and assistance provided by Patricia Guerrero, Comite ejecutivo internacional de la WILPF, Liga de Mujeres Desplazadas; Patricia Ramirez Parra, Ruta Pacifica de las Mujeres--Regional Santander; and Luisa Cabal, Center for Reproductive Rights. Researched and written by Boris Wijkström and Lucinda O’Hanlon. Supervised and edited by Carin Benninger-Budel. For more information, please contact OMCT's Women's Desk at the following email address: [email protected] Geneva, October 2003 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preliminary Observations 3 1.1 Colombia’s International and Domestic Obligations 3 1.2 General Observations on the Human Rights Situation in Colombia 5 2. General Status of Women in Colombia 10 3. Violence against Women Perpetrated by the State and Armed Groups 12 3.1 Violence against Women Human Rights Defenders 13 3.2 Child Soldiers 14 4. Internally Displaced Women 15 5. Violence Against Women in the Family 16 5.1 Domestic Violence 16 5.2 Marital Rape 20 6. Violence Against Women in the Community 20 6.1 Rape and Sexual Violence 20 6.2 Trafficking 22 7. Reproductive Rights 24 8. Conclusions and Recommendations 24 2 1. Preliminary Observations The submission of information specifically relating to violence against women to the United Nations Committee against Torture forms part of OMCT’s Violence against Women programme which focuses on integrating a gender perspective into the work of the five “mainstream” United Nations human rights treaty monitoring bodies. -

NARCOTRAFFIC AS CONNECTED POLITICAL CRIME in COLOMBIA: the FARC CASE Andrea Mateus-Rugeles* Paula C

University of Miami Inter-American Law Review Volume 51 Number 2 Spring 2020 Article 3 5-8-2020 Narcotraffic as Connectedolitical P Crime in Colombia: the FARC Case Andrea Mateus-Rugeles Universidad del Rosario School of Law Paula C. Arias University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Andrea Mateus-Rugeles and Paula C. Arias, Narcotraffic as Connectedolitical P Crime in Colombia: the FARC Case, 51 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 1 (2020) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol51/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter-American Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARCOTRAFFIC AS CONNECTED POLITICAL CRIME IN COLOMBIA: THE FARC CASE Andrea Mateus-Rugeles* Paula C. Arias** I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 4 II. THE FARC—THE OLDEST GUERRILLA GROUP IN THE AMERICAS, AND ITS INVOLVEMENT WITH THE MOST PROFITABLE ILLEGAL BUSINESS ON THE CONTINENT. .................................................................. 6 A. History of the FARC ............................................................ 6 1. Phase One: Germination and Consolidation (1962- 1973) ............................................................................... 8 2. Phase Two: Crisis and Division (1973-1980) ................ 9 3. Phase Three: Rebound and Boom (1980-1989) ........... 10 4. Phase Four: Deterioration and Delegitimisation * Associate professor of International Law, Universidad del Rosario, School of Law (Bogotá, Colombia). -

Digital and Social Media and Protests Against Large-Scale Mining Projects in Colombia Specht, D

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Gold, power, protest: Digital and social media and protests against large-scale mining projects in Colombia Specht, D. and Ros-Tonen, M.A.F. This is a copy of the accepted author manuscript of the following article: Specht, D. and Ros-Tonen, M.A.F. (2017) Gold, power, protest: Digital and social media and protests against large-scale mining projects in Colombia, New Media & Society, 19 (12), pp. 1907-1926. The final definitive version is available from the publisher, Sage at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444816644567 © The Author(s) 2017 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Gold, power, protest: Digital and social media and protests against large- scale mining projects in Colombia Doug Specht University of Westminster, UK Mirjam AF Ros-Tonen University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Abstract Colombia’s Internet connectivity has increased immensely. Colombia has also ‘opened for business’, leading to an influx of extractive projects to which social movements object heavily. Studies on the role of digital media in political mobilisation in developing countries are still scarce. Using surveys, interviews, and reviews of literature, policy papers, website and social media content, this study examines the role of digital and social media in social movement organisations and asks how increased digital connectivity can help spread knowledge and mobilise mining protests. -

Countryreport Colombia Wfpr

ABOUT The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida, is a government agency working on behalf of the Swedish parliament and government, with the mission to reduce poverty in the world. Through our work and in cooperation with others, we contribute to implementing Sweden’s Policy for Global Development Established by the inventor of the Web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the World Wide Web Foundation seeks to establish the open Web as a global public good and a basic right, creating a world where everyone, everywhere can use the Web to communicate, collaborate and innovate freely. The World Wide Web Foundation operates at the confluence of technology and human rights, targeting three key areas: Access, Voice and Participation. Karisma Foundation is a woman-driven, digital rights NGO, hoping to continue its future work in the defense of freedom of expression, privacy, access to knowledge and due process through research and advocacy from gender perspective, filling a much-needed void in Colombia. Karisma focus has been politics at the intersection of human rights and digital technology. Karisma has worked with diverse communities, including: Librarians, journalists, persons with visual disability, women’s rights advocates to strengthen the defense of human rights in digital spaces. Karisma often works jointly with other NGOs and networks that support their actions and projects. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Background to the study Population Poverty Millennium Development Goals (MDG) Context of internet and information society -

Inter-American Defense College

INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE COLLEGE REPORT TO THE COMMITTEE ON HEMISPHERIC SECURITY SEMINAR ON SMALL ARMS TRAFFICKING FORT LESLEY J. McNAIR WASHINGTON, DC 20319-5066 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This academic seminar was organized by the Inter-American Defense College (IADC), in coordination with the Committee of Hemispheric Security (CHS) and the Secretariat of Multidimensional Security of the Organization of American States (OAS). The event responded to Resolution AG/RES 2627 (XLI-O/11) of the General Assembly, which seeks to promote an agenda for reducing illicit small arms trafficking in the Americas. Accordingly, the General Assembly resolved to invite the IADC to organize a “Seminar on Small Arms Trafficking” for its students, the CHS, and other associated OAS offices. The seminar’s events and outcomes complemented and contributed to the OAS-based annual meeting of the Inter-American Convention Against Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms (CIFTA), which shared invited participants, experts, and ideas. SEMINAR OVERVIEW The 3-day seminar was divided into two parts: 1) an official meeting of the CHS; and 2) structured panel and working group discussions hosted by the IADC that operated according to College standards of non-attribution. Expert panels were comprised of diverse institutional perspectives, and working groups critically examined the multifaceted priorities for addressing challenges of illicit arms trafficking. Themes analyzed, with embedded expert support, included: 1. Marking and Tracing of Firearms; 2. Stockpile Management and Destruction of Firearms and Munitions; 3. Strengthening Ballistic and Forensic Identification; 4. Coordinating Mechanisms for Regional and Sub-regional Enforcement; 5. Promoting Implementation of Firearms Agreement and Strengthening Legislation; 6. -

Global Information Society Watch 2009 Report

GLOBAL INFORMATION SOCIETY WATCH (GISWatch) 2009 is the third in a series of yearly reports critically covering the state of the information society 2009 2009 GLOBAL INFORMATION from the perspectives of civil society organisations across the world. GISWatch has three interrelated goals: SOCIETY WATCH 2009 • Surveying the state of the field of information and communications Y WATCH technology (ICT) policy at the local and global levels Y WATCH Focus on access to online information and knowledge ET ET – advancing human rights and democracy I • Encouraging critical debate I • Strengthening networking and advocacy for a just, inclusive information SOC society. SOC ON ON I I Each year the report focuses on a particular theme. GISWatch 2009 focuses on access to online information and knowledge – advancing human rights and democracy. It includes several thematic reports dealing with key issues in the field, as well as an institutional overview and a reflection on indicators that track access to information and knowledge. There is also an innovative section on visual mapping of global rights and political crises. In addition, 48 country reports analyse the status of access to online information and knowledge in countries as diverse as the Democratic Republic of Congo, GLOBAL INFORMAT Mexico, Switzerland and Kazakhstan, while six regional overviews offer a bird’s GLOBAL INFORMAT eye perspective on regional trends. GISWatch is a joint initiative of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and the Humanist Institute for Cooperation with -

Istanbul Aydin University Institute of Social Sciences

ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON THE PURCHASING BEHAVIOR OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS WHO COLLECT ITEMS AS A HOBBY IN COLOMBIA THESIS Juan Sebastian VIUCHE NIETO Department of Business Business Management Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Farid HUSEYNOV JANUARY 2019 ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON THE PURCHASING BEHAVIOR OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS WHO COLLECT ITEMS AS A HOBBY IN COLOMBIA THESIS Juan Sebastian VIUCHE NIETO (Y1612.130132) Department of Business Business Management Program Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Farid HUSEYNOV JANUARY 2019 ii To my Mother Carmenza and my Father Jose, the beacon of this adventure. Thank you, for everything. iii DECLARATION I declare that this thesis titled as “How social media makes an impact on the purchase behavior of university students collects items as a hobby in Colombia” has been written by myself in accordance with the academic rules. I also declare that all the materials benefited in this thesis consist of the mentioned resources in the reference list. I verify all these with my honor. Juan Sebastian VIUCHE NIETO iv FOREWORD This thesis is the effort of my parents, the reason of why I am here, in the other side of the world, fulfilling my goals. I want to give special thanks to my supervisor professor Farid Huseynov, his support was vital and exceptional in every aspect of this research work. Collectibles are my passion and the reason I chose this specific topic, I cannot be more grateful on how many happy moments being part of this world it gave me. -

The Effects of Punishment of Crime in Colombia on Deterrence, Incapacitation, and Human Capital Formation

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Guarin, Arlen; Medina, Carlos; Tamayo, Jorge Andres Working Paper The Effects of Punishment of Crime in Colombia on Deterrence, Incapacitation, and Human Capital Formation IDB Working Paper Series, No. IDB-WP-420 Provided in Cooperation with: Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Washington, DC Suggested Citation: Guarin, Arlen; Medina, Carlos; Tamayo, Jorge Andres (2013) : The Effects of Punishment of Crime in Colombia on Deterrence, Incapacitation, and Human Capital Formation, IDB Working Paper Series, No. IDB-WP-420, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Washington, DC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/89133 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IDB WORKING PAPER SERIES No. -

Migration and Violence: Lessons from Colombia for the Americas” a Workshop of the Transatlantic Forum on Migration and Integration (TFMI)

“Migration and Violence: Lessons from Colombia for the Americas” A workshop of the Transatlantic Forum on Migration and Integration (TFMI) Bogotá D.C – June 29, 2012 Participants • Clemencia Ramírez – IOM Bogotá • Fernando Protti Alvarado – UNHCR Costa Rica • Diana Trimiño – UNCHR • Marcel Arevalo – Coordinator, Poverty and Migration Studies; Academic Advisor, Latin American Faculty of Social Science; Member, FLACSO Guatemala • Miguel Vilches Hinojosa – Professor, Department of Legal Studies, Universidad Iberoamericano, León • Daniel Gonzalez – Program Director, AVINA • Patricia Weiss Fagen – Georgetown University • Fabio Lozano – Codhes • Alejandro Aponte – Expert, Criminal Law and Internal Displacement, Universidad Javeriana • Andrés Célis – UNHCR Colombia • Sandra Quintero Ovalle – Mexican Analyst • Manuel Tenorio – Mexican Lawyer • John Jairo Montoya – Director SJR Colombia • Luis Fernando Gómez – Coordinador, SJR LAC • Marco Velázquez – Professor, Universidad Javeriana • Sebastián Rodríguez Alarcón – Law, Universidad los Andes • Jorge Salcedo – PhD Student, Law, Universidad del Rosario Conference Organization Team • Roberto Vidal • Ian McGrath • Micah Bump • Merlys Mosquera • Luis Aparicio Sponsors • The German Marshall Fund of the Unites States (GMF) • Robert BoschStiftung (Germany) • Refugee Research Network (funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Canada) Rapporteur of the Conference • Jorge Salcedo – Political Scientist, PhD Candidate, Law, Universidad del Rosario Migration and Violence: Lessons from Colombia for the Americas 29 June 2012 Introduction The conference, “Migration and Violence: Lessons from Colombia to the Americas” was held in Bogotá D.C., Colombia at the headquarters of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana on June 29, 2012. The main objective of the conference was to foster the development ofinter-disciplinary academic research in Central America and Mexico regarding the relationship between violence, particularly narco-violence, and migration.