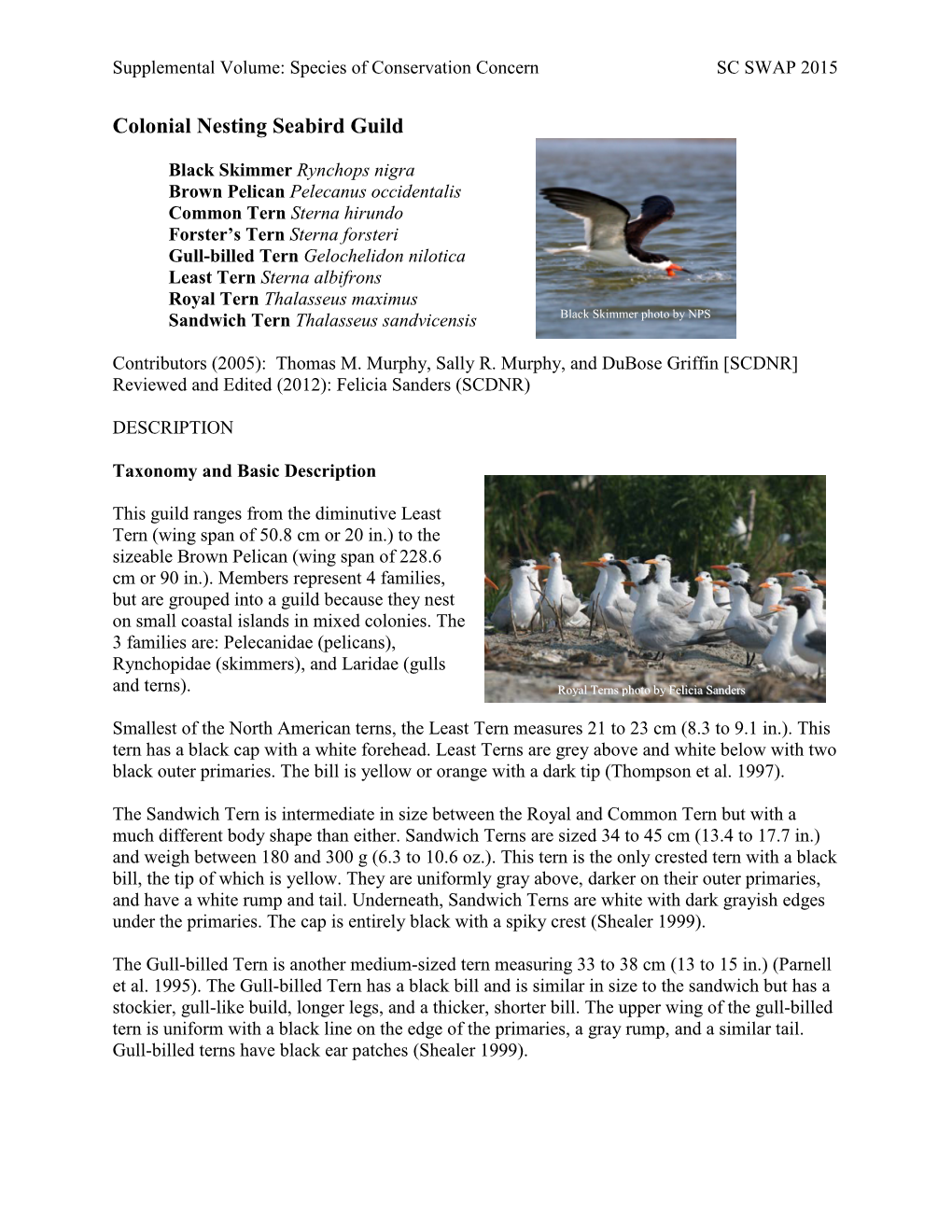

Colonial Nesting Seabird Guild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna Maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity William James Ihle College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Ihle, William James, "Aspects of Breeding Behavior of the Royal Tern (Sterna maxima) with Particular Emphasis on Prey Size Selectivity" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625247. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4aq2-2y93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE ROYAL TERN (STERNA MAXIMA) n WITH PARTICULAR EMPHASIS ON PREY SIZE SELECTIVITY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Biology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William J. Ihle 1984 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 1MI \MLu Author Approved, April 1984 Mitchell A. Byrd m Stewart A. Ware R/ft R. Michael Erwin DEDICATION To Mom, for without her love and encouragement this thesis would not have been completed. FRONTISPIECE. Begging royal tern chick and its parent in the creche are surrounded by conspecific food parasites immediate!y after a feeding. -

Sandwich Terns to Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico, with Our Observations of Single Individuals in 1986 and Again in 2008

NOTES SANDWICH TERNS ON ISLA RASA, GULF OF CALIFORNIA, MEXICO ENRIQUETA VELARDE, Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Pesquerías, Universidad Veracruzana, Hidalgo 617, Col. Río Jamapa, Boca del Río, Veracruz, México, C.P. 94290; [email protected] MARISOL TORDESILLAS, Álvaro Obregón 549, Col. Poblado Alfredo V. Bonfi l, Cancún, Quintana Roo, México, C.P. 77560; [email protected] In North America the Sandwich Tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis) breeds locally along marine coasts and offshore islands primarily of the southeastern United States and Caribbean (AOU 1998). In these areas it commonly nests in dense colonies of the Royal Tern (T. maximus) and Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla; Shealer 1999). It winters along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico from Florida to the West Indies, more rarely as far south as southern Brazil and Uruguay. It also winters on the Pacifi c coast, mainly from Oaxaca, Mexico, south to Panama (Howell and Webb 1995), occasionally to Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru (AOU 1998). As there are no breeding colonies on the Pacifi c coast, all birds wintering there are believed to represent migrants from Atlantic and Caribbean colonies (Collins 1997, Hilty and Brown 1986, Ridgely 1981, Ridgely and Greenfi eld 2001). Sandwich Terns have occasionally wandered as far north as eastern Canada (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland) and inland to Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois (AOU 1998, Clapp et al. 1983). In the Pacifi c vagrants are known from California and the Hawaiian Islands (Hamilton et al. 2007, AOU 1998). Here we report vagrancy of Sandwich Terns to Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico, with our observations of single individuals in 1986 and again in 2008. -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

Lady's Island Lake Tern Report 2011

Lady’s Island Lake Tern Report 2011. David Daly, C.J.Wilson & Tony Murray 1 The author and the area ranger, on behalf of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (Department of Arts, Heritage & and the Gaeltacht), wish to acknowledge the support of the landowners and rights holders of Our Ladys Island Lake with the management of the tern conservation project throughout the year. 2 Contents page Site synopsis…………………………………………………………….. 4 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………… 5 Site map…………………………………………………………………… 6 Lady’s Island Tern Report Summary…………………………………………………………………… 7 Methods Preparatory work…………………………………………………………… 8 Vegetation management Predator control…………………………………………………………… 9 Monitoring of disturbance…………………………………………………. 13 Feral Greylag Geese……………………………………………………….. 14 Location of island and colonies Censusing ………………………………………………………………. 15 Water levels……………………………………………………………. 19 Weather…………………………………………………………………. 21 Location of colonies…………………………………………………… 22 Productivity & feeding biology of Roseate & Sandwich terns ………… 23 Species accounts . Black-headed Gulls……………………………………………………… 24 Mediterranean Gulls…………………………………………………….. 27 Common Gulls………………………………………………………….. 30 Sandwich Terns………………………………………………………… 31 Common/Arctic terns…………………………………………………… 37 Little Terns………………………………………………………………. 42 Roseate Terns……………………………………………………………. 43 Other species……………………………………………………………… 51 3 SITE SYNOPSIS SITE NAME: LADY'S ISLAND Site codes SAC: 000704 SPA: 004010 Lady’s Island Lake is situated in the extreme south-east of Ireland and is comprised of a shallow, brackish coastal lagoon separated from the sea by a 200 meter wide sand and shingle barrier. The lake is 3.7 km in length and 1.3 km at its widest, southerly point. The lake and its two islands, Inish and Sgarbheen, are designated Special Protection Areas (SPA), holding internationally important numbers of breeding terns. This site is of high conservation importance, having three habitats which are listed on Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive and one of these (lagoons) with priority status. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

1. Background EAAFP Seabird Species Prioritization Project 2015

Coordinating Seabird Conservation along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Mayumi SATO1, Yat-Tung YU2, Mark CAREY3, Paul O’NEILL3 1. BirdLife International Tokyo, 2. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, 3. Department of the Environment, Australian Government [email protected] 1. Background The East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership Seabird Working Group East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF) is one of nine major migratory Over 150 seabird species inhabit the EAAF, some which have long trans- routes, extending from arctic Russia and Alaska through South-East and equatorial migration routes while others move at a smaller regional scale. East Asia to Australia and New Zealand. The East Asian-Australasian Although some species have very large populations, many species are Flyway Partnership (EAAFP) was established in 2006 as an informal, declining or are facing a high risk of extinction due to several ongoing voluntary international framework aimed at coordinating the conservation threats at their breeding and wintering sites. To achieve positive for migratory waterbirds and their habitat. conservation outcomes, a joint and equal responsibility for the conservation of seabirds is urgently required across the region. Unfortunately, Partners National governments (17) IGOs (6) conservation, management, education, and research activities for seabirds in International NGOs (10) the EAAF have lacked coordination in terms of objectives, field methods, International private enterprise (1) reporting and information exchange. The EAAFP Seabird -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Laughing Gulls Breed Primarily Along the Pacific Coast of Mexico and the Atlantic and Caribbean Coasts from S

LAUGHING GULL Leucophaeus atricilla non-breeding visitor, regular winterer L.a. megalopterus Laughing Gulls breed primarily along the Pacific coast of Mexico and the Atlantic and Caribbean coasts from s. Canada to Venezuela, and they winter S to Peru and the Amazon delta (AOU 1998, Howell and Dunn 2007). It and Franklin's Gull were placed along with other gulls in the genus Larus until split by the AOU (2008). Vagrant Laughing Gulls have been reported in Europe (Cramp and Simmons 1983) and widely in the Pacific, from Clipperton I to Wake Atoll (Rauzon et al. 2008), Johnston Atoll (records of at least 14 individuals, 1964-2003), Palmyra, Baker, Kiribati, Pheonix, Marshall, Pitcairn, Gambier, and Samoan Is, as well as Australia/New Zealand (King 1967; Clapp and Sibley 1967; Sibley and McFarlane 1968; Pratt et al. 1987, 2010; Garrett 1987; Wragg 1994; Higgins and Davies 1996; Vanderwerf et al. 2004; Hayes et al. 2015; E 50:13 [identified as Franklin's Gull], 58:50). Another interesting record is of one photographed attending an observer rowing solo between San Francisco and Australia at 6.5° N, 155° W, about 1400 km S of Hawai'i I, 1-2 Nov 2007. They have been recorded almost annually as winter visitors to the Hawaiian Islands since the mid-1970s, numbers increasing from the NW to the SE, as would be expected of this N American species. The great majority of records involve first-year birds, and, despite the many records in the S Pacific, there is no evidence for a transient population through the Hawaiian Islands, or of individuals returning for consecutive winters after departing in spring. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

Fish Prey of the Black Skimmer Rynchops Niger at Mar Chiquita, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

199 FISH PREY OF THE BLACK SKIMMER RYNCHOPS NIGER AT MAR CHIQUITA, BUENOS AIRES PROVINCE, ARGENTINA ROCÍO MARIANO-JELICICH, MARCO FAVERO & MARÍA PATRICIA SILVA Laboratorio de Vertebrados, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Funes 3250 (B76002AYJ), Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina ([email protected]) Received 13 September 2002, accepted 20 February 2003 SUMMARY MARIANO-JELICICH, R., FAVERO, M. & SILVA, M.P. 2003. Fish prey of the Black Skimmer Rynchops niger at Mar Chiquita, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Marine Ornithology 31: 199-202. We studied the diet of the Black Skimmer Rynchops niger during the non-breeding season (austral summer-autumn 2000) by analyzing 1034 regurgitated pellets from Mar Chiquita, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Fish was the main prey, with five species identified: Odontesthes argentinensis, O. incisa, Anchoa marinii, Engraulis anchoita and Pomatomus saltatrix. O. incisa and O. argentinensis were present in all the sampled months, showing also larger values of occurrence, numerical abundance and importance by mass than other items. The average size of the fish was 73±17 mm in length and 2.2±1.7 g in mass. Significant differences were observed in the comparison of the occurrence, importance by number and by mass throughout the study period. The presence of fish in the diet of the Black Skimmer coincides with a study carried out on the North American subspecies. Our analysis of the diet suggests that skimmers use both estuarine and marine areas when foraging. Keywords: Black Skimmer, Rynchops niger,Argentina, South America, diet INTRODUCTION METHODS Black Skimmers Rynchops niger are known by the morphological Study area characteristics of the bill and their particular feeding technique, We studied the diet of Black Skimmers by analyzing 1034 skimming over the water surface to catch fish and other prey. -

Lowrie, K., M. Friesen, D. Lowrie, and N. Collier. 2009. Year 1 Results Of

2009 Year 1 Results of Seabird Breeding Atlas of the Lesser Antilles Katharine Lowrie, Project Manager Megan Friesen, Research Assistant David Lowrie, Captain and Surveyor Natalia Collier, President Environmental Protection In the Caribbean 200 Dr. M.L. King Jr. Blvd. Riviera Beach, FL 33404 www.epicislands.org Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 3 GENERAL METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Field Work Overview ........................................................................................................................... 4 Water‐based Surveys ...................................................................................................................... 4 Data Recorded ................................................................................................................................. 5 Land‐based Surveys ......................................................................................................................... 5 Large Colonies ................................................................................................................................. 6 Audubon’s Shearwater .................................................................................................................... 7 Threats Survey Method .................................................................................................................