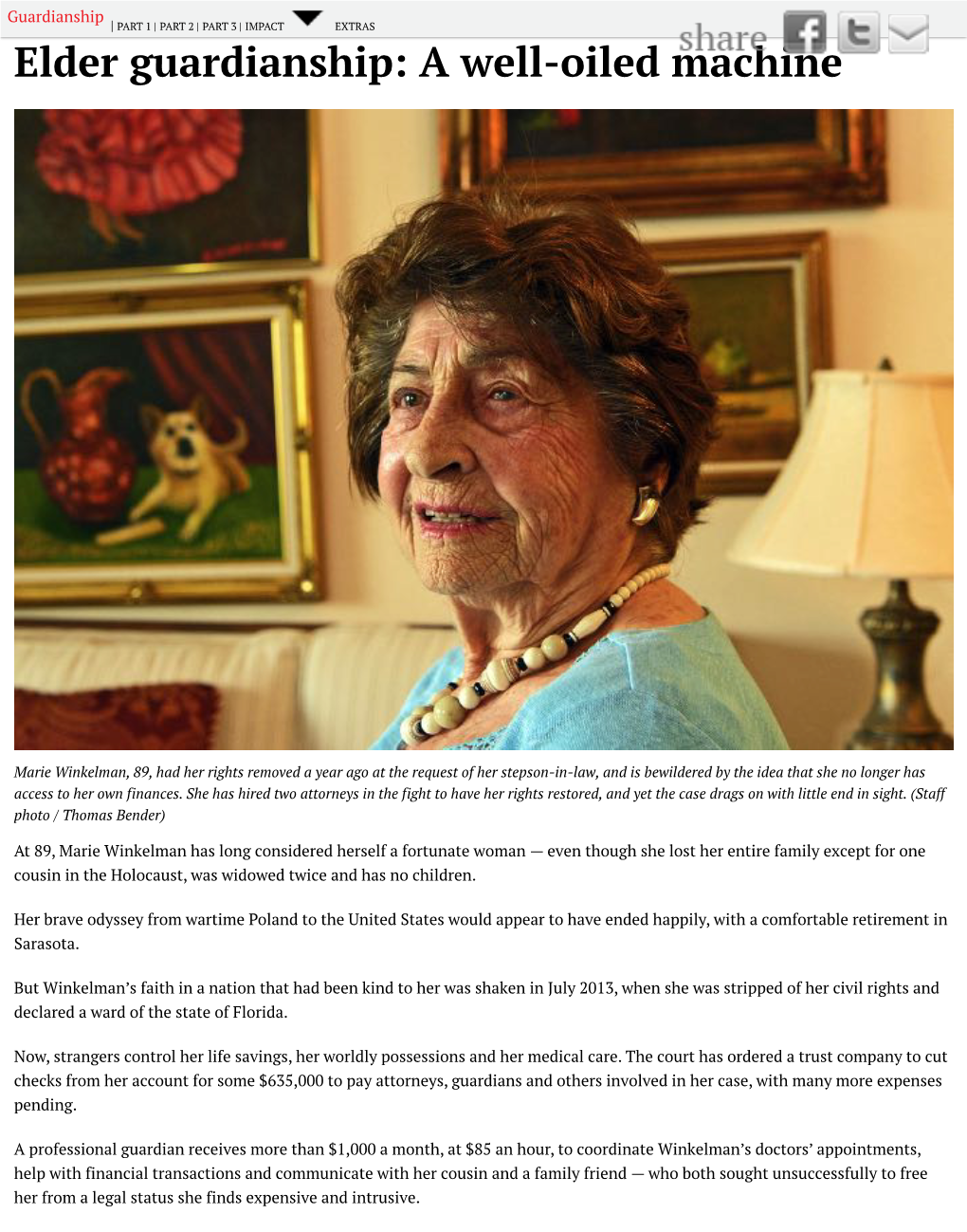

Elder Guardianship: a Well-Oiled Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida State Courts 2016-2017 Annual Report a Preparatory Drawing of One of the Two Eagle Sculptures That Adorn the Rotunda of the Florida Supreme Court

Florida State Courts 2016-2017 Annual Report A preparatory drawing of one of the two eagle sculptures that adorn the rotunda of the Florida Supreme Court. Sculpted by Panama City artist Roland Hockett, the copper eagles, which have graced the rotunda since 1991, represent American patriotism and the ideals of justice that this country strives to achieve. Mr. Hockett donated a drawing of each sculpture to the court in July 2017. The Supreme Court of Florida Florida State Courts Annual Report July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 Jorge Labarga Chief Justice Barbara J. Pariente R. Fred Lewis Peggy A. Quince Charles T. Canady Ricky Polston C. Alan Lawson Justices Patricia “PK” Jameson State Courts Administrator The 2016 – 2017 Florida State Courts Annual Report is published by The Office of the State Courts Administrator 500 South Duval Street Tallahassee, FL 32399-1900 Under the direction of Supreme Court Chief Justice Jorge Labarga State Courts Administrator Patricia “PK” Jameson Innovations and Outreach Chief Tina White Written/edited by Beth C. Schwartz, Court Publications Writer © 2018, Office of the State Courts Administrator, Florida. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Message from the Chief Justice .......................................................................................................................... 1 July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017: The Year in Review ............................................................................................... 7 Long-Range Issue #1: Deliver Justice Effectively, Efficiently, and Fairly -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD·-SE:NATE. June 14

7776 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD·-SE:NATE. JuNE 14, PUBLIC BILLS, ~ESOLUTIONS, AND l\IEMORL.t\LS. can Dramatists and Composers, protesting against the second- Under clause 3 of Rule XXII, bills, resolutions, and memorials class postal 1:ates .of the war-revenue act and asking its repeal; ''"ere introduced :m<l severally referred as follows: to the Comrmttee on Ways and l\feans. By Mr. l\IcARTHUR: A bill (H. R. 12463) to designate the na- By .Mr. DOOLirr:rr~~: Petition of cit~zens of Eskridge, Kans:, · tional service flag and national service emblem; to define or- favormg war prohibition! ~ the C?n;urutte~ on the Judiciary. ganizations and persons 'vho shall be entitled to display and . By .l\1~. FULLE~ of llllnOis.: Petltwn of the Woman's Chm"ch wear the same; and for other purposes; to the Committee on the 1 F.edeiatwn of ChiCago, favo1:mg passage of the minimum-wage Judiciary. bill for women; to the Committee on Labor. By l\Ir. l\IADDEN: Resolution (H. Res. 392) requesting infor-· By. 1\lr. GOULD: Petit~on of sundry Bible class members of mation at to the number of men in the sen·ice of the Food Admin- Baptist C~urch of Summ1.t, .N. Y., fayoring war prohibition; to i trator and Fuel Administrator who are within the draft age;. to the , Commi~t~e on the Judiciary. tile Committee on l\Iilitary Affairs. Also, peti.twn of th~ Potter (N.. Y:). Women's Christian Tern- By l\lr. CRAl\ITON: Resolution (H. Res. 394) requesting the perance.l!ruon, favormg war prohibition; to the Committee on President to report to the House of Representatives whether any the Judicmry. -

Local Arrangements Guide for 2020

SCS/AIA DC-area Local Arrangements Guide Contributors: • Norman Sandridge (co-chair), Howard University • Katherine Wasdin (co-chair), University of Maryland, College Park • Francisco Barrenechea, University of Maryland, College Park • Victoria Pedrick, Georgetown University • Elise Friedland, George Washington University • Brien Garnand, Howard University • Carolivia Herron, Howard University • Sarah Ferrario, Catholic University This guide contains information on the history of the field in the DC area, followed by things to do in the city with kids, restaurants within walking distance of the hotel and convention center, recommended museums, shopping and other entertainment activities, and two classically-themed walking tours of downtown DC. 2 History: In the greater Washington-Baltimore area classics has deep roots both in academics of our area’s colleges and universities and in the culture of both cities. From The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore—with one of the oldest graduate programs in classics in the country to the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, VA, classicists and archaeologists are a proud part of the academic scene, and we take pleasure in inviting you during the SCS and AIA meetings to learn more about the life and heritage of our professions. In Maryland, the University of Maryland at College Park has strong programs and offers graduate degrees in classical languages, ancient history, and ancient philosophy. But classics also flourishes at smaller institutions such as McDaniel College in Westminster, MD, and the Naval Academy in Annapolis. Right in the District of Columbia itself you will find four universities with strong ties to the classics through their undergraduate programs: The Catholic University of America, which also offers a PhD, Howard University, Georgetown University, and The Georgetown Washington University. -

Arlington Memorial Bridge Adjacent to the Base of the Lincoln Memorial

Arlington Memorial Bridge HAER No. DC-7 Adjacent to the base of the Lincoln Memorial, spanning the Potomac River to Arlington Cemetery, VA. Washington District of Columbia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, DC 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD ARLINGTON MEMORIAL BRIDGE HAER No. DC-7 Location: Adjacent to the base of the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., spanning the Potomac River to Arlington Cemetery, Arlington, VA. UTM: 18/321680/4306600 Quad.: Washington West Date of Construction: Designed 1929, Completed 1932 Architects: McKim, Mead and White, New York, New York; William Mitchell Kendall, Designer Engineer: John L. Nagle, W.J. Douglas, Consulting Engineer, Joseph P. Strauss, Bascule Span Engineer Contractor: Forty contractors under the supervision of the Arlington Bridge Commission Present Owner: National Capital Region National Park Service Department of the Interior Present Use: Vehicular and pedestrian bridge Significance: As the final link in the chain of monuments which start at the Capitol building, the Arlington Memorial Bridge connects the Mall in Washington, D.C. with Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Designed to connect, both physically and symbolically, the North and the South, this bridge, as designed in the Neoclassical style, complements the other monumental buildings in Washington such as the White House, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial. Memorial Bridge was designed by William Mitchell Kendall while in the employ of McKim, Mead and White, a prominent architectural firm based in New York City. Although designed and built almost thirty years after the McMillan Commission had been disbanded, this structure reflects the original intention of the Commission which was to build a memorial bridge on this site which would join the North and South. -

Historical Perspective of Heritage Legislation

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF HERITAGE LEGISLATION. BALANCE BETWEEN LAWS AND VALUES HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF HERITAGE LEGISLATION. BALANCE BETWEEN LAWS AND VALUES 2 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF HERITAGE LEGISLATION. BALANCE BETWEEN LAWS AND VALUES International conference October 12-13, 2016 Niguliste Museum Tallinn, Estonia Conference proceedings Conference team: ICOMOS Estonia NC; ICLAFI; Estonian Academy of Arts; Tallinn Urban Planning Department Division of Heritage Protection; Estonian National Heritage Board Publication: ICOMOS Estonia NC; ICLAFI; Estonian Academy of Arts Editors: Riin Alatalu, Anneli Randla, Laura Ingerpuu, Diana Haapsal Design and layout: Elle Lepik Photos: authors, Tõnu Noorits Tallinn 2017 ISBN 978-9949-88-197-0 (pdf) The conference and meetings of ICLAFI and Nordic-Baltic ICOMOS National Committees were supported by: Estonian Academy of Arts, Tallinn Urban Planning Department Division of Heritage Protection, National Heritage Board, Ministry of Culture, Nordic Council of Ministers Published with the financial support from Estonian Cultural Foundation © ICOMOS ESTONIA NC, 2017 © ICLAFI, 2017 © Authors of the articles, 2017 international council on monuments and sites HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF HERITAGE LEGISLATION. BALANCE BETWEEN LAWS AND VALUES 3 CONTENTS 4 TOSHIYUKI KONO Foreword 81 JAMES K. REAP WHAT’S OLD IS NEW AGAIN: CHARLES XI’S 1666 CONSERVATION ACT VIEWED FROM 21ST CENTURY AMERICA 5 RIIN ALATALU Conference proceedings 6 THOMAS ADLERCREUTZ THE ROYAL PLACAT OF 1666. BRIEFLY 91 ERNESTO BECERRIL MIRÓ and ROBERTO -

Genocide-Holodomor 1932–1933: the Losses of the Ukrainian Nation”

TARAS SHEVCHENKO NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF KYIV NATIONAL MUSEUM “HOLODOMOR VICTIMS MEMORIAL” UKRAINIAN GENOCIDE FAMINE FOUNDATION – USA, INC. MAKSYM RYLSKY INSTITUTE OF ART, FOLKLORE STUDIES, AND ETHNOLOGY MYKHAILO HRUSHEVSKY INSTITUTE OF UKRAINIAN ARCHAEOGRAPHY AND SOURCE STUDIES PUBLIC COMMITTEE FOR THE COMMEMORATION OF THE VICTIMS OF HOLODOMOR-GENOCIDE 1932–1933 IN UKRAINE ASSOCIATION OF FAMINE RESEARCHERS IN UKRAINE VASYL STUS ALL-UKRAINIAN SOCIETY “MEMORIAL” PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC- EDUCATIONAL WORKING CONFERENCE “GENOCIDE-HOLODOMOR 1932–1933: THE LOSSES OF THE UKRAINIAN NATION” (October 4, 2016, Kyiv) Kyiv 2018 УДК 94:323.25 (477) “1932/1933” (063) Proceedings of the International Scientific-Educational Working Conference “Genocide-Holodomor 1932–1933: The Losses of the Ukrainian Nation” (October 4, 2016, Kyiv). – Kyiv – Drohobych: National Museum “Holodomor Victims Memorial”, 2018. x + 119. This collection of articles of the International Scientific-Educational Working Conference “Genocide-Holodomor 1932–1933: The Losses of the Ukrainian Nation” reveals the preconditions and causes of the Genocide- Holodomor of 1932–1933, and the mechanism of its creation and its consequences leading to significant cultural, social, moral, and psychological losses. The key issue of this collection of articles is the problem of the Ukrainian national demographic losses. This publication is intended for historians, researchers, ethnologists, teachers, and all those interested in the catastrophe of the Genocide-Holodomor of 1932–1933. Approved for publication by the Scientific and Methodological Council of the National Museum “Holodomor Victims Memorial” (Protocol No. 9 of 25 September 2018). Editorial Board: Cand. Sc. (Hist.) Olesia Stasiuk, Dr. Sc. (Hist.) Vasyl Marochko, Dr. Sc. (Hist.), Prof. Volodymyr Serhijchuk, Dr. Sc. -

2015 Conference Program

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER, 12 Democracy in the former Soviet republics: Trends and THURSDAY, 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Idiosyncracies Kunihiko Imai, Elmira College; Robert Nalbandov, Utah State University REGISTRATION 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. How the Euro Divides the Union: Economic Adjustment and Loews Philadelphia Hotel: Floor Third -Lobby Support for Democracy in Europe Klaus Armingeon, University of Bern; Kai Guthmann, University of Bern; THURSDAY, 8:45 a.m. to 10:15 a.m. David Weisstanner, University of Bern Elites and the Welfare State in a New Democracy Taesim Kim, A-1 Competing for Power and Influence in a Partisan Age University of Connecticut Paper Session Chair: 8:45 to 10:15 am Mary Stegmaier, University of Missouri Loews Philadelphia Hotel: Floor Third - Jefferson Discussant: Participants: Miguel Glatzer, La Salle University Party Polarization by Vote Type in Congress, 1947 - 2012 Eric Paul Svensen, University of Texas G-1 Cases, Interests, and Actors in American and British Foreign Presidential Signing Statements: Tools of Polarization Brandon Policy Russell Johnson, Monmouth University Paper Session Voting for Gun Control Jordan Ragusa, College of Charleston 8:45 to 10:15 am Chair: Loews Philadelphia Hotel: Floor Third - Washington B Mack David Mariani, Xavier University Participants: Discussant: British Non-Intervention in the American Civil War Mark Lanethea Mathews-Schultz, Muhlenberg College William Petersen, Bethany College Enhancing Global Leadership and Order: The US' African B-1 Creating Political Space Growth and Opportunity Act. Peter Sekyere, Brock Panel University 8:45 to 10:15 am The dilemma of the American policy towards Islamists in Egypt Loews Philadelphia Hotel: Floor Fourth - Congress A since Morsi's Ouster Marwa Hamouda Ahmed Wasfy, Cairo Participants: University Minor Party Movements: Minor Parties, Social Movements, and Chair: Fringe Interests in America Catherine Kane, University of Paul S. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2020

Part 3 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 7-15 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLY Vol. LXXXVIII No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2020 $2.00 Zelenskyy faces challenges of history Oleh Sentsov: The nail that will not bend and diplomacy in Israel and Poland memoration on such terms and told Israeli media that Mr. Putin was spreading lies to conceal the Soviet Union’s responsibility for the war along with that of Nazi Germany. In this highly tricky situation, Mr. Zelenskyy bided his time and did not con- firm whether he would be going to Jerusalem and Warsaw until the last min- ute. While still preoccupied with the after- math of a Ukrainian airliner’s downing in Tehran and the return of the bodies, President Zelenskyy nevertheless made his line known. The Times of Israel reported on January 19, after interviewing him in Kyiv, and on the day he announced he would be going to Israel: “He speaks at length about the Holodomor, the Soviet- imposed deliberate famine of 1932-1933, Olena Blyednova which killed millions, and with great Oleh Sentsov during his presentation on January 25 in New York. The discussion was respect for the victims of the Holocaust – moderated by Razom volunteer Maria Genkin. and the need to bring a belated, honest his- torical account of these events into the by Irene Jarosewich in Switzerland – that he does not consider open. He acknowledges but says less on the himself to be, foremost, a Russian political Presidential Office of Ukraine issue of Ukrainians’ participation in NEW YORK – Ukrainian film director prisoner. -

Art Theft, Art Vandalism, and Guardianship in U.S. Art Institutions

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Art theft, art vandalism, and guardianship in U.S. art institutions. Katharine L. Salomon University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Salomon, Katharine L., "Art theft, art vandalism, and guardianship in U.S. art institutions." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3028. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3028 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ART THEFT, ART VANDALISM, AND GUARDIANSHIP IN U.S. ART INSTITUTIONS By Katharine L. Salomon B.A, Transylvania University, 1990 M.S., University of Louisville, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Interdisciplinary and Graduate Studies of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies School of Interdisciplinary and Graduate Studies University of Louisville Louisville, KY -

Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 Hearings Before the Subcommittee

1.72 Is that generally always worked out previously so we are not deal ing with any guardianship arrangements even on 'a temporary basis ~ Mr. BARKER. Yes, Ms. Marks. It is fully understood by the States in which these families are serving as host families. This arrangement is worked out and there is no legal guardianship. They fully understand that the Iridian AP PEN DIX children are merely coming to reside m the home of the host family. They are coming there along with the other children from that home, but they belong, for example, at Navajo or they belong at Hopis or Fort Hall or someplace and they are members of the families of Additional Material Submitted for the Hearing Record those reservations. Ms. MARKS. The last quick question, you mentioned to Ms. Foster that all the children generally leave together. Are they generally returned together at the same time ~ So in other words, if a child is not returned when at the end of the school year for some reason--the family wishes him to stay--what is the procedure ~ , STATEMENT OF RICK LAVIS, DEPUTY ASSISTANT SECRETARY-INDIAN AFFAIRS Are you aware of these as the church is aware of these ~ Do they (PROGRAM OPERATIONS) BEFORE THE HEARING OF THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INDIAN as as AFFAIRS AND PUBLIC LANDS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERIOR AND INSULAR AFFAIRS, get special permission from church staff well the parents or U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON S. 1214, THE "INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT does this become an interpersonal relationship between the two sets OF 1977", FEBRUARY 9, 1978. -

Stop Heritage Crime: Coins, Archaeological and Ethnographic Material” (Lillestrøm, January 2011); “Illicit Objects: Between Legal Framework and Practical Handling

StopStop hheritageeritage ccrimerime Good practices and recommendations The project „Legal and illicit trade with cultural heritage. Research and education platform of experience exchange in the fi eld of prevention from crime against cultural heritage” Warszawa 2011 StopStop hheritageeritage ccrimerime Good practices and recommendations The project „Legal and illicit trade with cultural heritage. Research and education platform of experience exchange in the fi eld of prevention from crime against cultural heritage” Warszawa 2011 Partners Supported by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism Publisher: ul. Szwoleżerów 9, 00-464 Warszawa 22 628 48 41, e-mail: [email protected] Project coordinator: Aleksandra Chabiera Technical coordinator: Michał Aniszewski Scientific editing: Liv Ramskjaer, Anne Nyhamar, Aleksandra Chabiera, Michał Aniszewski Proofreading: English Prep Graphic design: Direktpoint - Tomasz Świtała, Wojciech Rojek Printing and binding: Wydawnictwo Polskiego Związku Niewidomych Sp. z o.o Print run: 1000 egz. Illustrations: The National Heritage Board of Poland Archive, sxc.hu, shutterstock © Copyright by the National Heritage Board of Poland, Warsaw 2011 ISBN 978-83-931656-5-0 Table of content X Introductionuction 6 Overview 9 Sidsel Bleken – Legal and illicit trade in cultural heritage 11 11 Marianne Lehtimäki – Looting and illicit trade in cultural heritage – problems that cannot be solved by one state or one sector alone 13 13 Aleksandra Chabiera – -

Colorado Office of Public Guardianship Policy 6

COLORADO OFFICE OF PUBLIC GUARDIANSHIP POLICY 6: PROGRAM SERVICES STANDARDS Policy 6. Program Services Standards The Colorado Office of Public Guardianship’s (OPG) design and operation shall follow the tenets of the National Guardianship Association (NGA) Ethical Principles and the NGA Standards of Practice to assure that these principles guide program design and day to day services. National Guardianship Association Standards of Practice for Agencies and Programs Providing Guardianship Services Standards; National Guardianship Association Ethical Principles; National Guardianship Association Standards of Practice. Policy 6.1. Applicable Law and General Standards a. The Office of Public Guardianship Act, C.R.S. §§ 13-94-101 – 13-94-111 (2017, 2019). https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/5e186416-ff24-4eab-afa0- ac6ec0dd0943/?context=1000516 Highlights: • Provide guardianship services to indigent and incapacitated adults who reside in the 2nd Judicial District/Denver County: o (A) Have no responsible family members or friends who are available and appropriate to serve as guardian; o (B) Lack adequate resources to compensate a private guardian and pay the costs associated with an appointment proceeding; o (C) Are not subject to a petition for appointment of guardian filed by a county adult protective services unit or otherwise authorized by section § 26-3.1-104, C.R.S. • Gather data to help the general assembly determine the need for, and the feasibility of, a statewide office of public guardianship; • The office is a pilot program, to be evaluated and then continued, discontinued, or expanded at the discretion of the general assembly in 2021 [2023]; • Director Report due before or on January 1, 2023; • Treat liberty and autonomy as paramount values for all state residents; • Permit incapacitated adults to participate as fully as possible in all decisions that affect them; and • Assist incapacitated adults to regain or develop their capacities to the maximum extent as possible.