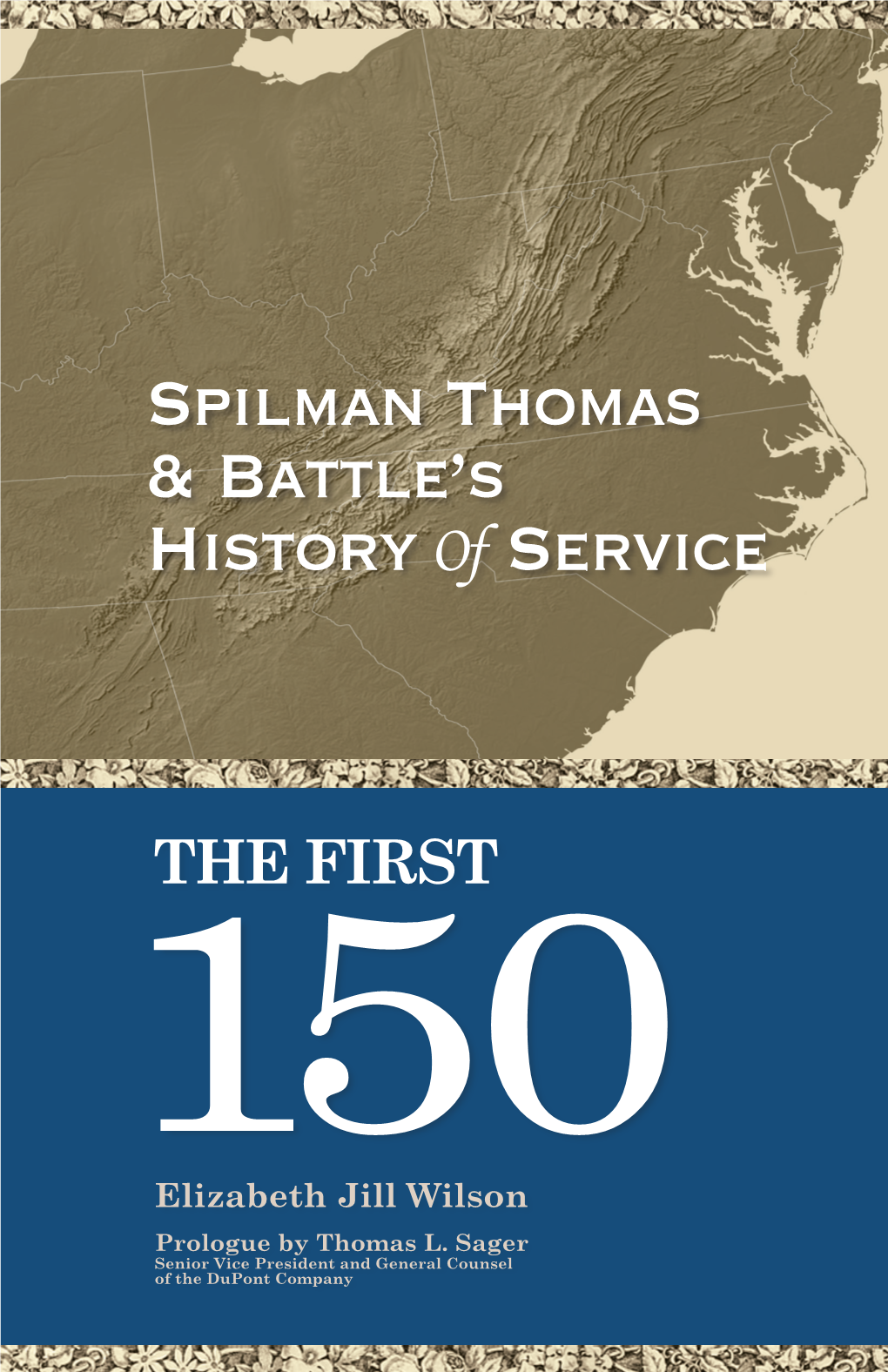

Spilman Thomas & Battle's History of Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to Black Horse Cavalry Defend Our Beloved Country, by Lewis Marshall Helm

Index to Black Horse Cavalry Defend Our Beloved Country, by Lewis Marshall Helm http://innopac.fauquiercounty.gov/record=b1117236 Index courtesy of Fauquier County Public Library (http://fauquierlibrary.org) Name Subject Page Abel, Charles T. a prisoner dies of illness 225 Abel, Charles T. BH brief biography / service record 263 Abel, George W. enlists with BH 67 Abel, George W. was captured and sent to Old Capitol Prison 140 Abel, George W. BH brief biography / service record 263 Abell, Charles T. Gerardis captured Alexander in Culpeper sold it to Gen. 172 Abingdon Washington 15 Accotink Run BH engages Union troops 62 Payne memo, speculates on Jackson had Achilles he lived in the past 301 Adams (Mr.) Turner diary mentions 100 see also Slaves and Negros (terms were African Americans indexed as they appeared in the text) African-Americans Mosby blamed for support of 248 home state of Private Wilburn relative of Alabama Robert Smith 245 Albemarle Cavalry diarist describes 41 Albemarle County Union sends in cavalry raids 192 Aldie Turner describes Union advance toward 145 Aldie Stuart's cavalry fights around 164 Aldie road "guide" claims Jackson is moving along 116 sold Alexander home, Abingdon, to Gen. Alexander, Gerard Washington 15 family settled along banks of Potomac in Alexander, John IV 1659 15 Alexander, Mark hijinks w/William Payne 3 Alexandria is being bombarded, topic of chapter 14, 15 Alexandria Artillery is formed and attracts volunteers 15 Alexandria Light Artillery fires first round 30 Alexandria Light Artillery takes out Cub Run bridge 35 Alexandria Pike BH does picket duty along 13 Alexandria Railroad trains are commandeered 19 Alexandria Rifles Alexander Hunter is transferred to BH 160 Alexandria Sentinel issues call to arms 15 Alexandria Turnpike its importance is noted 4 Alexandria Turnpike Jackson to arrive at 104 Alexandria Turnpike section from Waterloo to Amissville 153 Name Subject Page Allen (Col.) Payne memo, recalls attack let by 298 Alrich Union moves toward Richmond from 200 Alston, Harold exchanged from Ft. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Oooo: DEDICATED to ALL BARRICKMAN-BARRACKMANS WHO HAVE TAKEN SUCH PRIDE in the PART THEIR FAMILY HAS PLAYED in AMERICAN HISTORY

• JUL * 1^)2 INDEXED G. 3M THE BARRACKMAN-BARRICKMAN FAMILIES OF WEST VIRGINIA COMPILED BY: JUHB Bo BAREKMAN 3302 IV. DIVERSE* CHICAGO 47, ILL. BR 8-8486 GENEALOGICAL SOOSTY OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SANTS R5288 DATE MICROFICHED US/MM / PROJECT and G. S. FlCHE # CALL# 26 frt 7-/0J •4 ioit oooo: DEDICATED TO ALL BARRICKMAN-BARRACKMANS WHO HAVE TAKEN SUCH PRIDE IN THE PART THEIR FAMILY HAS PLAYED IN AMERICAN HISTORY. NOT ONLY THIS FAMILY IN WEST VIRGINIA, BUT IN EARLY VIRGINIA,, MARYLAND, PENNSYL* VANIA, AND EVERY OUTPOST OF CIVILIZATION IN THE AMERICAN COLONIES. THEY WERE HARD WORKING—DEEPLY RELIGIOUS—JUST AND PAIR. THEY WERE TILLERS OF THE SOIL, MEN WHO FOUGHT IN ALL OP OUR WARS TO AID IN FREEDOM. TODAY BARRICKMAN-BARRACKMANS SERVE THROUGH OUT THE WORLD AS MINISTERS, COMMANDING OFFICERS IN THE VARIOUS SERVICES, DOCTORS, LAWYERS, EDUCATORS, AND HOMEMAKERS. MANY STILL ARE FARMERS. ALL INTER* ESTED IN ONE COMMON CAUSE—FREEDOM,, IN EVERY MEANING OF THE WORD. MAY THIS GREAT FAMILY GROW AND PROSPERo >CG2 Credits Given *% To Ruth Barekman of Bloomington^ Illinois® who not only diligently typed most of the following records,, but helped In filling In family groups o To Mary T« Rafterye who helped me assemble material© handled some of my correspondence^, and also faithfully typed on the West Virginia llne0 To Marian Collore who supplied all paper materials and ditto mater ial sP and ran off one-hundred eoples of the West Virginia booko To DeCota Barrlekman VarnadoP who worked so hard and long on her branch of the West Virginia Barrlokmanso Mrso Varnado spent untold hours of research and letter writing, not to mention long distance oallso Mrso Varnado Is given full credit as the oompllor of the John So Barrlekman familyo To Earl Lo Core. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

2011-08 Knapsack

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table The same rain falls on both friend and foe. August 8, 2011 Volume 11 Our 126th Meeting Number 8 ‘Colonel Black Jack’ Travis to Discuss E. Porter Alexander at August 8 Meeting Our August speaker, „Colonel Black Jack‟ group for several years, Jack currently lives in Travis, is an author, historian, and professional Wilmington, N.C. At our August meeting, he will Civil War re-enactor. give us a presentation on “E. Porter Alexander, Rebel Gunner,” the subject of his latest book. Jack was raised in Allapattah, Fla., and earned his bachelor‟s degree in administration from Lakeland College, Wis., with a minor in history. EDITOR’S NOTE: Per our bylaws, a business meeting also will be held at our August event. ~ E. Porter Alexander ~ Edward Porter Alexander was born on May 26, 1835, in Washington, Ga. Alexander began his service in the Confederate army as a captain of engineers, but is best known as an artilleryman who was prominent in many of the major battles of the Civil War. Jack at Alexander’s Grave Prior to his retirement, he was the national sales manager for a large orthopaedic company and owned Action Orthopaedics in Raleigh. Jack has written several historical articles for national publications and is the author of Men of God, Angels of Death, for which he received the Gold Medal Book Award from the United Daughters of the Confederacy. He also serves Alexander commanded the Confederate artillery as a board member of the Lower Cape Fear for Longstreet‟s corps at Gettysburg, guiding Historical Society as well as the Federal Point the massive cannonade before what commonly Historical Preservation Society. -

H. Doc. 108-222

912 Biographical Directory to California in 1877 and established a wholesale fruit and D commission business; was a member of the National Guard of California, and subsequently assisted in the organization DADDARIO, Emilio Quincy, a Representative from of the Coast Guard, of which he later became brigadier Connecticut; born in Newton Center, Suffolk County, Mass., general in command of the Second Brigade; elected as a September 24, 1918; attended the public schools in Boston, Republican to the Fifty-second Congress (March 4, 1891- Mass., Tilton (N.H.) Academy, and Newton (Mass.) Country March 3, 1893); declined to be a candidate for renomination Day School; graduated from Wesleyan University, Middle- in 1892; in 1894 settled in New York City, where he became town, Conn., in 1939; attended Boston University Law interested in the automobile industry; retired to Westport, School 1939-1941; transferred to University of Connecticut N.Y., in 1907; died in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, November and graduated in 1942; was admitted to the bar in Con- 24, 1911; interment in Hillside Cemetery, Westport, N.Y. necticut and Massachusetts in 1942 and commenced the practice of law in Middletown, Conn.; in February 1943 en- CUTTS, Charles, a Senator from New Hampshire; born listed as a private in the United States Army; assigned in Portsmouth, N.H., January 31, 1769; graduated from Har- to the Office of Strategic Services at Fort Meade, Md.; served vard University in 1789; studied law; admitted to the bar overseas in the Mediterranean Theater; was separated -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1963, Volume 58, Issue No. 2

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. 58, No. 2 JUNE, 1963 CONTENTS PAGE The Autobiographical Writings of Senator Arthur Pue Gorman John R. Lambert, Jr. 93 Jonathan Boucher: The Mind of an American Loyalist Philip Evanson 123 Civil War Memoirs of the First Maryland Cavalry, C. S.A Edited hy Samuel H. Miller 137 Sidelights 173 Dr. James B. Stansbury Frank F. White, Jr. Reviews of Recent Books 175 Bohner, John Pendleton Kennedy, by J. Gilman D'Arcy Paul Keefer, Baltimore's Music, by Lester S. Levy Miner, William Goddard, Newspaperman, by David C. Skaggs Pease, ed.. The Progressive Years, by J. Joseph Huthmacher Osborne, ed., Swallow Barn, by Cecil D. Eby Carroll, Joseph Nichols and the Nicholites, by Theodore H. Mattheis Turner, William Plumer of New Hampshire, by Frank Otto Gatell Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, by Dorothy M. Brown Brewington, Chesapeake Bay Log Canoes and Bugeyes, by Richard H. Randall Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan, Revolutionary Rifleman, by Frank F. White, Jr. de Valinger, ed., and comp., A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters, by George Valentine Massey, II Klein, ed.. Just South of Gettysburg, by Harold R. Manakee Notes and Queries 190 Contributors 192 Annual Subscription to the Magazine, t'f.OO. Each issue $1.00. The Magazine assumes no responsibility for statements or opinions expressed in its pages. Richard Walsh, Editor C. A. Porter Hopkins, Asst. Editor Published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore 1, Md. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Md. > AAA;) 1 -i4.J,J.A.l,J..I.AJ.J.J LJ.XAJ.AJ;4.J..<.4.AJ.J.*4.A4.AA4.4..tJ.AA4.AA.<.4.44-4" - "*" ' ^O^ SALE HISTORICAL MAP OF ST. -

Steubenville Span Opens

Steubenville span opens STEUBENVILLE, Ohio (AP) — Officials from two states say a newly opened Ohio River bridge might still be the dream it was for 30 years had an Ohio lawyer not made a nuisance of himself from time to time. Bridge from Page A1 "No doubt about it. There were some politicians who hated to hear from Nate Stern," Mayor David Hindman said. "They knew who he was when he himself and others was all that kept applied pressure all those times. He could be quite the project from falling apart on vociferous when he wanted to know what was being some occasions. done to get this bridge built." Celeste recalled the commitment Stern joined Ohio Gov. Richard Celeste, West Stern coaxed from him eight years Virginia Gov. Gaston Caperton and Sens. Robert Byrd ago when he ran for his first term as and Jay Rockefeller, both DW.Va., in yesterday's governor. dedication of the $65 million, sixlane Veterans "Nate Stern told the truth when he said I promised to complete the Memorial Bridge. Highway 22 (expressway bypass) Most of the approximately 500 people attending the project if elected. The truth is that ceremony huddled under umbrellas in the middle of was the only highway project I the bridge. But about 30 veterans representing promised anywhere in Ohio." servicemen from World War I to the Vietnam War Celeste yesterday announced that remained uncovered and at attention. Ohio Transportation Director Ber After the ceremonies, the bridge was opened nard Hurst has arranged to open bids around 6:30 p.m., allowing the first regular traffic to on contracts for the last two uncom cross. -

The Civil War in Fairfax County, Virginia the Civil War in Fairfax County, Virginia Was the Most Divisive and Destructive Period in the County’S History

(ANNE putting in section headings only 9/3) Confidential Draft August 31, 2020 rvsd 9/7/20 The Civil War in Fairfax County, Virginia The Civil War in Fairfax County, Virginia was the most divisive and destructive period in the county’s history. Soon after President Abraham Lincoln was elected President on November 6, 1860. local citizens began holding a series of public meetings at the courthouse to discuss whether Virginia should remain in the Union or secede and join the nascent Confederate States of America. Remain or Secede? Resolutions were adopted to expel pro-Union, anti-slavery men from the county. Several resolutions passed defending slavery. Other resolutions supported arming and funding local militia. The Fairfax Cavalry, under Captain M. D. Ball, and the Fairfax Rifles, under Captain William H. Dulany, drilled and paraded together on the courthouse yard throughout early 1861. Within ten days of Virginia’s vote to secede on May 23, 1861, the first armed conflict occurred in Fairfax County on June 1, in and around the same courthouse grounds where those public debates on secession began. Captain John Quincy Marr of the Warrenton Rifles was killed in the skirmish with Company B, Second U.S. Cavalry. He has been memorialized as the first Confederate officer to die in the Civil War. South Controls Western Half of County Through March 1862 In July, roughly 18,000 soldiers of the Army of Northeastern Virginia under the command of Union General Irvin McDowell advanced through the county. The Federals marched to the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford (July 18) and subsequently the Battle of First Manassas or Bull Run (July 21). -

A N N E T T E P O L a N

A N N E T T E P O L A N 4719 30TH STREET, N.W. WASHINGTON, DC 20008 (202) 537-2908 [email protected] www.annettepolan.com EMPLOYMENT 2013 - Principal Insight Institute www.insightinstitute.org 2009 - Corcoran College of Art at George Washington University, Professor Emerita 1980 – 2009 Corcoran College of Art + Design, Professor 2004 – 2007 Founder and Chair of Faces of the Fallen www.facesofthefallen.com 2008 – 2013 Principal CAPITAL ARTPORTS www.capitalartports.com EDUCATION Corcoran College of Art+ Design of Art, Washington, DC, Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia, Drawing and Painting Ecole du Louvre, Paris, France, Art History Hollins University, Virginia, B.A., Art History AWARDS 2018 Visual Voices Lecture, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia 2015 – 2016 ARTCART, Research Center for Art and Culture, Columbia University 2011 Artist in Residence, The Highlands, North Carolina 2011 Distinguished Artist, Montgomery College 2010 Artist in Residence, Spring Island, South Carolina 2009 Professor Emerita, Corcoran College of Art at George Washington University 2008 Hollins University Distinguished Alumnae Award 2006 Department of Defense Outstanding Public Service Award 2006 Cosmos Club Award Nomination 2004 Mayor’s Award in the Arts, Honorable Mention 2002 Vermont Studio Center, Artist Residency, Johnson, Vt. 1999 Batuz Foundation, Société Imaginaire Program, Altzella, Germany 1998 Distinguished Alumnae Award, The Baldwin School, Bryn Mawr, Pa. 1993 D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Grants in Aid Award 1985 D.C. Commission -

Institutions

Section Five INSTITUTIONS Correctional Institutions Health Facilities Public Colleges & Universities Private & Denominational Colleges 630 WEST VIRGINIA BLUE BOOK CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES Huntington Work/Study Release Center 1236 5th Avenue, Huntington, WV 25701-2207 Administrator: Renae Stubblefield. Secretary: Jacqueline Jackson. The Huntington Work/Study Release Center is a community-based correctional facility operated by the Division of Corrections, which is an agency under the Department of Military Affairs and Public Safety. Huntington Work/Study Release Center houses both male and female offenders with a capacity to house approximately 66 inmates. Inmates are carefully screened through a risk assessment classification method for participation in the work release program. The program’s primary objective is to assist the inmate in making a successful transition from incarceration to the community. This is accomplished by providing them an opportunity to take advantage of educational/vocational and work programs within the community. As they are gradually readjusting, the program’s intent is to reduce anxieties and frustrations often associated with immediate release back into society. Offenders become responsible for themselves and are less of a burden to West Virginia taxpayers while at work release. They are required to pay rent, medical expenses, child support, restitution and any fines they’ve incurred. They are also required to give back to the community by performing a minimum of 80 hours of community service work. Once community service is completed, inmates are permitted to seek employment in the local job market. Due to the demands of taking responsibility; meaningful employment is of primary importance, assuring the offender a successful work release experience.