Climbing Development Guidelines Draft 2 - Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yearbook.Pdf

P HILMONT SSS TTAFF A F FTA F YYY EARBOOK 2 0 1 020 0 3 Single Digits Chaplains John Clark Conservation Mark Anderson Food Services Steve Nelson Full-Time Maintenance Owen McCulloch Health Lodge Doug Palmer Logistics Greg Gamewell Mail Room Dave Kopsa Maintenance Merchandise Warehouse 11 Backcountry Staff Motor Pool Abreu News and Photo Services Apache Springs Rangers Baldy Town Registration Beaubien Security Black Mountain Services Carson Meadows Tooth of Time Traders Cimarroncito Clarks Fork 68 PTC Staff Clear Creek Handicrafts Crater Lake PTC Staff (group) Crooked Creek Philmont Museum & Seton Memorial Library Cyphers Mine Villa Philmonte Dan Beard Dean Cow 73 Memories Fish Camp French Henry Harlan Head of Dean COVER Hunting Lodge Philmont Patch Collection, photo by Jeremy Blaine Indian Writings Special thanks to Henry Watson for providing the patches Miners Park Miranda Phillips Junction C OURTESY OF YOUR Ponil 2 0 1 0 PHILNEWS STAFF Pueblano Rayado OWEN MCCULLOCH, Editor-in-chief Rich Cabins HENRY WATSON, NPS Manager Ring Place JEREMY BLAINE, NPS Assistant Manager Rocky Mountain Scout Camp BRYAN HAYEK, NPS Assistant Manager Sawmill MARGARET HEDDERMAN, NPS Assistant Manager Seally Canyon AMY HEMSLEY, Content Editor Urraca TARA RAFTOVICH, Design Editor Ute Gulch Whiteman Vega WRITERS : Timothy Bardin, Amy Hemsley Zastrow PHOTOGRAPHERS : Anita Altschul, Jeremy Blaine, Zac Boesch, Andrew Breglio, Matthew Martin, 47 Basecamp Staff Conan McEnroe, Tara Raftovich, Trevor Roberts, Activities Steve Weis Administration Office Backcountry Managers VIDEOGRAPHERS : Sean Barber, William Bus Drivers McKinney 2 “E FFECTIVE LEADERSHIP IS PUTTING FIRST THINGS FIRST . E FFECTIVE MANAGEMENT IS DISCIPLINE , CARRYING IT OUT . ” S TEPHEN R . -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

2001-2002 Bouldering Campaign

Climber: Angela Payne at Hound Ears Bouldering Comp Photo: John Heisel John Comp Photo: Bouldering Ears at Hound Payne Climber: Angela 2001-20022001-2002 BoulderingBouldering CampaignCampaign The Access Fund’s bouldering campaign hit bouldering products. Access Fund corporate and the ground running last month when a number community partners enthusiastically expressed of well-known climbers signed on to lend their their support for the goals and initiatives of support for our nationwide effort to: the bouldering campaign at the August •Raise awareness about bouldering among land Outdoor Retailer Trade Show held in Salt Lake managers and the public City. •Promote care and respect for natural places As part of our effort to preserve opportuni- visited by boulderers ties for bouldering, a portion of our grants pro- •Mobilize the climbing community to act gram will be targeted toward projects which responsibly and work cooperatively with land specifically address bouldering issues. Already, managers and land owners two grants that improve access and opportuni- •To protect and rehabilitate bouldering ties for bouldering have been awarded (more resources details about those grants can be found in this •Preserve bouldering access issue.) Grants will also be given to projects that •Help raise awareness and spread the message involve reducing recreational impacts at boul- about the campaign, inspirational posters fea- dering sites. The next deadline for grant appli- turing Tommy Caldwell, Lisa Rands and Dave cations is February 15, 2002. Graham are being produced that will include a Another key initiative of the bouldering simple bouldering “code of ethics” that encour- campaign is the acquisition of a significant ages climbers to: •Pad Lightly bouldering area under threat. -

2014 AMGA SPI Manual

AMERICAN MOUNTAIN GUIDES ASSOCIATION AMGA Single Pitch Instructor 2014 Program Manual American Mountain Guides Association P.O. Box 1739 Boulder, CO 80306 Phone: 303-271-0984 Fax: 303-271-1377 www.amga.com 1 AMGA Single Pitch Instructor Program © American Mountain Guides Association Participation Statement The American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) recognizes that climbing and mountaineering are activities with a danger of personal injury or death. Clients in these activities should be aware of and accept these risks and be responsible for their own actions. The AMGA provides training and assessment courses and associated literature to help leaders manage these risks and to enable new clients to have positive experiences while learning about their responsibilities. Introduction and how to use this Manual This handbook contains information for candidates and AMGA licensed SPI Providers privately offering AMGA SPI Programs. Operational frameworks and guidelines are provided which ensure that continuity is maintained from program to program and between instructors and examiners. Continuity provides a uniform standard for clients who are taught, coached, and examined by a variety of instructors and examiners over a period of years. Continuity also assists in ensuring the program presents a professional image to clients and outside observers, and it eases the workload of organizing, preparing, and operating courses. Audience Candidates on single pitch instructor courses. This manual was written to help candidates prepare for and complete the AMGA Single Pitch Instructors certification course. AMGA Members: AMGA members may find this a helpful resource for conducting programs in the field. This manual will supplement their previous training and certification. -

White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015

RUMNEY ROCKS CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015 Introduction The Rumney Rocks Climbing Area encompasses approximately 150 acres on the south-facing slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in Rumney, New Hampshire. Scattered across these slopes are approximately 28 rock faces known by the climbing community as "crags." Rumney Rocks is a nationally renowned sport climbing area with a long and rich climbing history dating back to the 1960s. This unique area provides climbing opportunities for those new to the sport as well as for some of the best sport climbers in the country. The consistent and substantial involvement of the climbing community in protection and management of this area is a testament to the value and importance of Rumney Rocks. This area has seen a dramatic increase in use in the last twenty years; there were 48 published climbing routes at Rumney Rocks in Ed Webster's 1987 guidebook Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and are over 480 documented routes today. In 2014 an estimated 646 routes, 230 boulder problems and numerous ice routes have been documented at Rumney. The White Mountain National Forest Management Plan states that when climbing issues are "no longer effectively addressed" by application of Forest Plan standards and guidelines, "site specific climbing management plans should be developed." To address the issues and concerns regarding increased use in this area, the Forest Service developed the Rumney Rocks Climbing Management Plan (CMP) in 2008. Not only was this the first CMP on the White Mountain National Forest, it was the first standalone CMP for the US Forest Service. -

What the New NPS Wilderness Climbing Policy Means for Climbers and Bolting Page 8

VERTICAL TIMES The National Publication of the Access Fund Summer 13/Volume 97 www.accessfund.org What the New NPS Wilderness Climbing Policy Means for Climbers and Bolting page 8 HOW TO PARK LIKE A CHAMP AND PRESERVE ACCESS 6 A NEW GEM IN THE RED 11 WISH FOR CLIMBING ACCESS THIS YEAR 13 AF Perspective “ The NPS recognizes that climbing is a legitimate and appropriate use of Wilderness.” — National Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis his past May, National Park Service (NPS) Director Jonathan Jarvis issued an order explicitly stating that occasional fixed anchor use is T compatible with federally managed Wilderness. The order (Director’s Order #41) ensures that climbers will not face a nationwide ban on fixed anchors in NPS managed Wilderness, though such anchors should be rare and may require local authorization for placement or replacement. This is great news for anyone who climbs in Yosemite, Zion, Joshua Tree, Canyonlands, or Old Rag in the Shenandoah, to name a few. We have always said that without some provision for At the time, it seemed that fixed anchors, technical roped climbing can’t occur — and the NPS agrees. the tides were against us, The Access Fund has been working on this issue for decades, since even before we officially incorporated in 1991. In 1998, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) that a complete ban on fixed issued a ban on fixed anchors in Wilderness (see photo inset) — at the time, it anchors in all Wilderness seemed that the tides were against us, that a complete ban on fixed anchors in all Wilderness areas was imminent. -

Indoor Climbing Facility Rules and Regulations

Indoor Climbing Facility - Climbing Tower Rules & Regulations 1. Every person entering the climbing area MUST check in with the Indoor Climbing Facility staff. 2. It is MANDATORY that climbers pass a skills check before engaging in any of the roped climbing. 3. Climbers must be at least 8 years of age or of average size for that age. Belayers must be at least 14 years of age and pass the belay skills test to receive approval to belay. 4. The climbing facility is to be used only during listed hours. The facility may be reserved for groups. For more information, contact Outdoor Adventures at 845-4511. 5. Climbers are required to use the ropes and belay anchors that are provided. Ropes for lead climbing are provided upon request by the Indoor Climbing Facility staff. 6. Belay devices must be attached to the harness of the belayer by means of a locking carabiner. You may use your own belay device if approved by the climbing facility staff. 7. A Figure-8 Follow Through knot with appropriate tail length must be tied directly into harness. Do not use belay loop or carabiner to tie in. 8. Harnesses and all other climbing equipment must be used as per the manufacturer’s instructions. All climbing gear must be approved by the UIAA or CE for climbing. 9. Climbers must be roped and on belay at all times, except while bouldering. 10. Do not climb past top-rope anchors. 11. Closed toed shoes are required on the climbing wall. 12. No food or beverages allowed on the safety deck surface. -

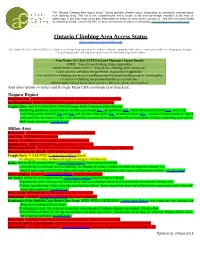

Ontario Climbing Area Access Status” Listing Provides Climber Access Information on Commonly Inquired-About Rock Climbing Areas

The “Ontario Climbing Area Access Status” listing provides climber access information on commonly inquired-about rock climbing areas. The list is not comprehensive and is based on the best knowledge available at the time of publication. If you have more up to date information or notice an error, please contact us. Any cliff not listed should be treated as closed. Consult the OAC for more information on status or ownership. [email protected] Ontario Climbing Area Access Status www.ontarioaccesscoalition.com The Ontario Access Coalition (OAC) is a volunteer, not-for-profit group that works with the climbing community, land owners, conservation authorities and property managers to keep climbing and bouldering areas open in an environmentally responsible manner. Area Name: ACCESS STATUS (Land Manager) Access Details. OPEN = Area allows climbing. Enjoy responsibly. OPEN WITH GUIDELINES = Area allows climbing, with restrictions. Learn, practice and share the guidelines. Buy permit if applicable. TOLERATED = Climbing access not formally permitted, but informally accepted. Tread lightly. CLOSED = Climbing not permitted in this area at this time. UNKNOWN = If you know about access to this area, please share with us. Area descriptions in italics and [Google Maps GPS coordinates] in [brackets]. Niagara Region Campden Crag: CLOSED (Niagara Conservation Authority) Climbing not permitted. Jordan Harbour: UNKNOWN (Unknown) Status unknown. Volunteers needed. Niagara Glen: OPEN WITH GUIDELINES (Niagara Parks Commission) [bouldering] Bouldering guidelines, waiver and fee in effect; see details here and guidelines here. Trails and closed boulders here. Free Glen bouldering guides available here and here and purchase 2014 guide here. Download waiver here. Completed waivers must be signed and returned to the Nature Centre or the Butterfly Conservatory for verification. -

Dorset a Guidebookto Thesportand Gaz Fry Onthepopularareteofmonsoonmalabar (6A)-Page76 Gaz Fry Printed Ineurope Onbehalfoflatitudepress Ltd

1 Portland Portland Dorset Lulworth Lulworth Mark Glaister Swanage Swanage Pete Oxley A guidebook to the sport and traditional climbing on Portland, Lulworth and Swanage Text and topos by Mark Glaister and Pete Oxley Edited by Stephen Horne and Alan James All uncredited photography by Mark Glaister Other photography as credited Printed in Europe on behalf of Latitude Press Ltd. Distributed by Cordee (www.cordee.co.uk) All maps by ROCKFAX Some maps based on original source data from openstreetmap.org Published by ROCKFAX in February 2012 © ROCKFAX 2012, 2005, 2000, 1994 www.rockfax.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 873341 47 6 Cover photo: Bridget Collier on Stalker's Zone (6a+) - page 158 Wallsend crags on Portland. This page: Gaz Fry on the popular arete of Monsoon Malabar (6a) - page 76 at the extensive Blacknor Central cliff on Portland. Contents 3 Introduction........................... 4 Acknowledgments...................... 10 Advertiser Directory .................... 12 Portland Portland Dorset Logistics ...................... 14 When to Go .......................... 16 Lulworth Lulworth Getting There ......................... 16 Accommodation - Portland ............... 18 Accommodation - Swanage, Lulworth ...... 20 Swanage Swanage Shops, Food and Drink.................. 22 Climbing Walls and Shops ............... 24 Dorset Climbing ...................... 26 Access .............................. 28 Bolting............................... 32 Gear and Tides........................ 34 Safety ............................... 36 Grades .............................. 38 Deep Water Soloing . 40 Graded List - Sport Routes .............. 42 Graded List - Traditional Routes........... 44 Destination Planner - Portland ........... -

National Tree Climbing Guide

National Tree Climbing Guide Forest 6700 Safety and Occupational Health April 2015 Service 2470 Silviculture 1 National Tree Climbing Guide 2015 Electronic Edition The Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), has developed this information for the guidance of its employees, its contractors, and its cooperating Federal and State agencies, and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone except its own employees. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this document is for the information and convenience of the reader, and does not constitute an endorsement by the Department of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. ***** USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. To file a complaint of discrimination, write: USDA, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, Office of Adjudication, 1400 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (866) 632-9992 (Toll-free Customer Service), (800) 877-8339 (Local or Federal relay), (866) 377-8642 (Relay voice users). Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................4 Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................7 1.1 Training .........................................................................................7 1.2 Obtaining Climbing Equipment ....................................................8 1.3 Terms and Definitions ...................................................................8 -

JANUARY MEETING Thursday, January 5Th, 7:30 P.M

JANUARY 1989 BOEING EMPLOYEES ALPINE SOCIETY, INC. PresideW;~,.,., ... Ken Johnson .. OU·31 .. 342-3974 Conservation ........ Eric Kasiulis.. 81-16 .. 773-57 42 Vice Pr~llnt;. .... .steveMason.. 97 -1.7 ...237 -5820 Echo Editor......... .Rob Freeman .. 6N -95 ..234-0468 Treas=.......... EIden Altiz.er .. 97-17 ...234'1721 Equipm~nt ........... Gareth Beale .. 7A-35 .. 865-5375 Secre~_ .. , .. _.. _•• JolinSumner.• 2.6-63 ... 655~9882 Librarian ............ Rik Anderson .. 76-15 .. 237 -9645 Past Pmsident..A:mbrose. Bittner.. OT-06 ... 342-5140 Membership.. Richard Babunovic.. 6L-15 .. 235-7085 ·Aeti,:tilts ..........MelissaStorey .. 1R-40... 633-3730 Programs.......... Tim .Backman . .4M-02.. 655-4502 Photo: Nevado Huandoy by Mark Dale D. OTT 5K-25 * FROM: 6L-15 R_BABUNOVIC JANUARY MEETING Thursday, January 5th, 7:30 P.M. Oxbow Rec Center CROSS COUNTRY SKI ROUTES ON MT. HOOD AND CENTRAL OREGON The January meeting will feature a slide presentation by Klindt vielbig, mountaineer as well as skier and author of "Cross Country Ski Routes Of Oregons' Cascades". Klindt will show slides illustrating many of the tours described in his book including Mt. )iood, the Wallowa Mtns., Crater Lake, Broken Top Crater, and Mt. Shasta. The diversity of ski tours makes this program a great aid in learning more about oregon skiing. Additionally, Boealps member Jim Blilie will give a short ~esentation on ice climbing. This is an appetizer to Jim's Feb.4-5 Leavenworth ice climbing/knuckle bashing weekend extravaganza. Belay Stance Well November's powder has yielded to December's thaw. Where has all the snow gone. What had started as a great ski season is now looking somewhat questionable. -

Climbing Management

CLIMBING MANAGEMENT A Guide to Climbing Issues and the Development of a Climbing Management Plan The Access Fund PO Box 17010 Boulder, CO 80308 Tel: (303) 545-6772 Fax: (303) 545-6774 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.accessfund.org The Access Fund is the only national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conserves the climbing environment. A 501(c)3 non-profi t supporting and representing over 1.6 million climbers nationwide in all forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is the largest US climbing organization with over 15,000 members and affi liates. The Access Fund promotes the responsible use and sound management of climbing resources by working in cooperation with climbers, other recreational users, public land managers and private land owners. We encourage an ethic of personal responsibility, self-regulation, strong conservation values, and minimum impact practices among climbers. Working toward a future in which climbing and access to climbing resources are viewed as legitimate, valued, and positive uses of the land, the Access Fund advocates to federal, state, and local legislators concerning public lands legislation; works closely with federal and state land managers and other interest groups in planning and implementing public lands management and policy; provides funding for conservation and resource management projects; develops, produces, and distributes climber education materials and programs; and assists in the acquisition and management of climbing resources. FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE ACCESS FUND: Visit http://www.accessfund.org. Copies of this publication are available from the Access Fund and will also be posted on the Access Fund website: http://www.accessfund.org.