Nestling Metabolism and Growth in the Black Noddy and White Tern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Problems on Tristan Da Cunha Byj

28 Oryx Conservation Problems on Tristan da Cunha ByJ. H. Flint The author spent two years, 1963-65, as schoolmaster on Tristan da Cunha, during which he spent four weeks on Nightingale Island. On the main island he found that bird stocks were being depleted and the islanders taking too many eggs and young; on Nightingale, however, where there are over two million pairs of great shearwaters, the harvest of these birds could be greater. Inaccessible Island, which like Nightingale, is without cats, dogs or rats, should be declared a wildlife sanctuary. Tl^HEN the first permanent settlers came to Tristan da Cunha in " the early years of the nineteenth century they found an island rich in bird and sea mammal life. "The mountains are covered with Albatross Mellahs Petrels Seahens, etc.," wrote Jonathan Lambert in 1811, and Midshipman Greene, who stayed on the island in 1816, recorded in his diary "Sea Elephants herding together in immense numbers." Today the picture is greatly changed. A century and a half of human habitation has drastically reduced the larger, edible species, and the accidental introduction of rats from a shipwreck in 1882 accelerated the birds' decline on the main island. Wood-cutting, grazing by domestic stock and, more recently, fumes from the volcano have destroyed much of the natural vegetation near the settlement, and two bird subspecies, a bunting and a flightless moorhen, have become extinct on the main island. Curiously, one is liable to see more birds on the day of arrival than in several weeks ashore. When I first saw Tristan from the decks of M.V. -

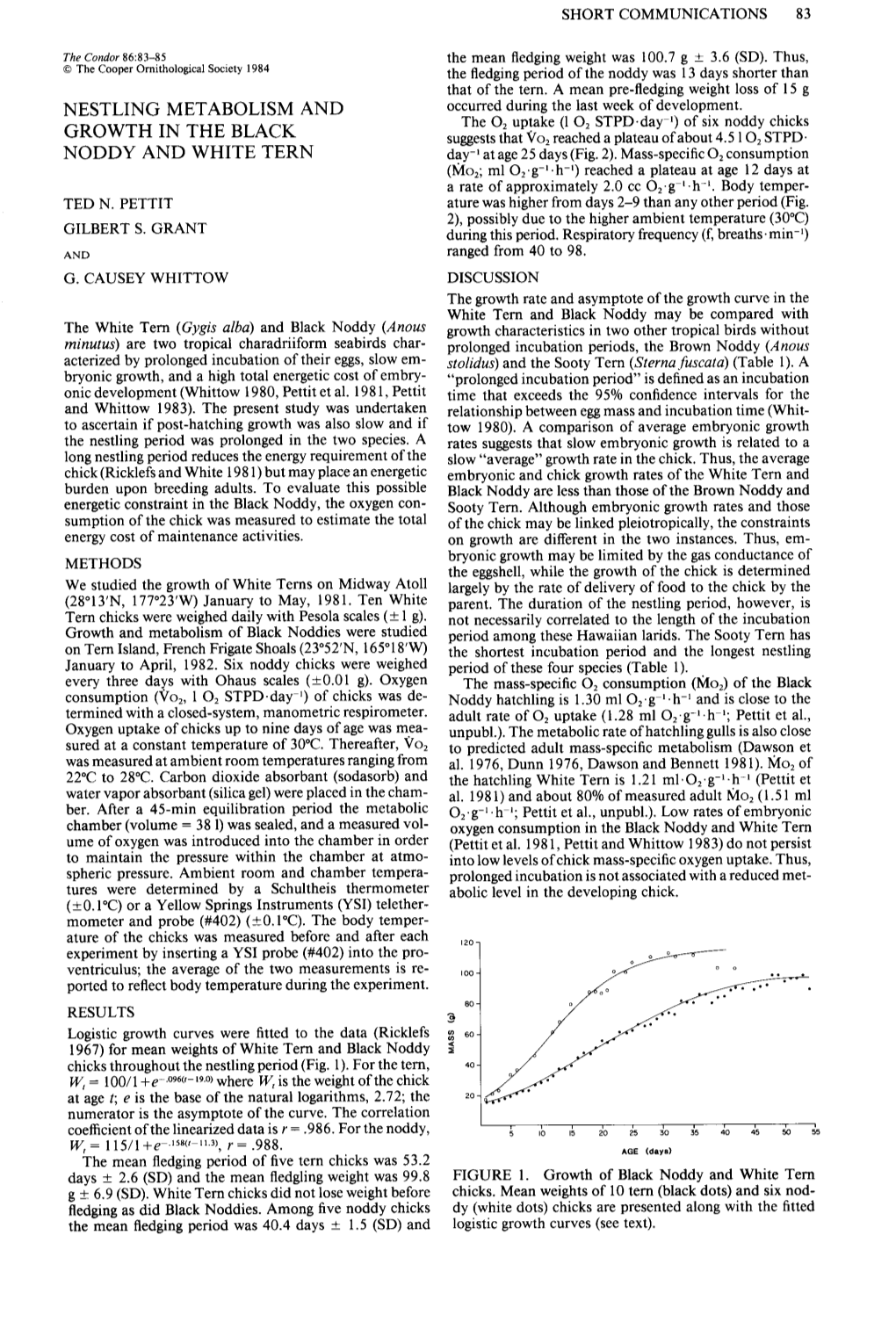

Red-Footed Booby Helper at Great Frigatebird Nests

264 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NECTS MEANS ECTS MEANS ICATE SAMPLE SIZE S.D. SAMPLE SIZE 70 IN DAYS FIGURE 2. Culmen length against age of Brown FIGURE 1. Weight against age of Brown Noddy Noddy chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. chicks on Manana Island, Hawaii in 1972. about the thirty-fifth day; apparently Brown Noddies on Christmas Island grow more rapidly than those on 5.26 g/day (SD = 1.18 g/day), and chick growth rate Manana. More data are required for a refined analysis and fledging age were negatively correlated (r = of intraspecific variation in growth rates of Brown -0.490, N = 19, P < 0.05). Noddy young. Seventeen of the chicks were weighed both at the This paper is based upon my doctoral dissertation age of fledging and from 3 to 12 days later; there was submitted to the University of Hawaii. I thank An- no significant recession in weight after fledging (t = drew J. Berger for guidance and criticism. The 1.17, P > 0.2), as suggested for certain terns (e.g., Hawaii State Division of Fish and Game kindly LeCroy and LeCroy 1974, Bird-Banding 45:326). granted me permission to work on Manana. This Dorward and Ashmole (1963, Ibis 103b: 447) mea- study was supported by the Department of Zoology sured growth in weight and culmen length of Brown of the University of Hawaii, by an NSF Graduate Noddies on Ascension Island in the Atlantic; scatter Fellowship, and by a Mount Holyoke College Faculty diagrams of their data indicate growth functions very Grant. -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

WHITE TERN Gygis Alba

WHITE TERN Gygis alba Other: Common White-Tern (1998-2000) G.a. candida (breeding) Fairy Tern, Manu-o-ku G.a. microrhyncha (vagrant) breeding visitor, indigenous; vagrant Three taxonomic groups of White Tern have been recognized, occurring in the tropical s. Atlantic Ocean (G.a. alba group), the Marquesas and Kiribati Is (microrhyncha group), and throughout the remainder of the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans, including Micronesia, Wake and Johnston atolls (Amerson and Shelton 1976, Rauzon et al. 2008), and the Hawaiian Islands (candida group). Various ornithologists consider these groups to comprise two or three different species (Pratt et al. 1987, AOU 1998) although, based on reported hybridization between microrhyncha and candida in the Marquesas Is (Holyoak and Thibault 1976), Higgins and Davies (1996) and the AOU (1998) consider these as subspecies groups within a single species. Olson (2005) has recently made a good case for treating microrhyncha and candida as separate species but molecular evidence suggests they should remain a single species (Yeung et al. 2009). See Niethammer and Patrick (1998) for more information on the natural history and biology of this species in the Hawaiian Islands. The great majority of White Terns breeding in the Hawaiian Islands are found in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where they occur on every island group, and number about 25,000 pairs in total population size (Table). The largest numbers by far are found on Midway, where the maturation of Casuarina trees providing nesting sites (cf. Fisher and Baldwin 1946, Rauzon and Kenyon 1984, Harrison 1990, Rauzon 2001; E 16:28-29) has lead to a large population increase, from only a few at the turn of the 20th century (Bryan 1906, Bartsch 1922) to about 3,000 in 1938 (Hadden 1941), to ~20,000 pairs in the mid 2010s. -

Class Three: Breeding

Class Three: Breeding WHERE DO SEABIRDS LAY THEIR EGGS? Nest or no nest? • Some species use no nesting material. E.g., the white tern lays a single egg on an open branch. • Some species use a very little bit of nesting material. E.g., the tufted puffin may use a few pieces of grass and a couple of feathers. • Some species build more substantial nests. E.g. kittiwakes cement their nests onto small cliff shelves by trampling mud and guano to form a base. And, some cormorants build large nests in trees from sticks and twigs. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 1 White tern • Also called fairy tern. • Tropical seabird species. • Lays egg on branch or fork in tree. No nest. • Newly hatched chicks have well developed feet to hang onto the nesting-site. White Tern. © Pillot, via Creative Commons. On the coast or inland? • Most seabird species breed on the coast and offshore islands. • Some species breed fairly far inland, but still commute to the ocean to feed. E.g., kittlitz’s murrelets nest on scree slopes on coastal mountains, and parents may travel more than 70km to their feeding grounds. • Other species breed far inland and never travel to the ocean. E.g., double crested cormorants breed on the coast, but also on lakes in many states such as Minnesota. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 2 NESTING HABITAT (1) Ground Some species breed on the ground. These species tend to breed in areas with little or no predation, such as offshore islands (e.g., terns and gulls) or in the Antarctic (e.g., penguins, albatross). -

Breeding Biology of the Brown Noddy on Tern Island, Hawaii

Wilson Bull., 108(2), 1996, pp. 317-334 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE BROWN NODDY ON TERN ISLAND, HAWAII JENNIFER L. MEGYESI’ AND CURTICE R. GRIFFINS ABSTRACT.-we observed Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus pileatus) breeding phenology and population trends on Tern Island, French Frigate Shoals, Hawaii, from 1982 to 1992. Peaks of laying ranged from the first week in January to the first week in November; however, most laying occurred between March and September each year. Incubation length was 34.8 days (N = 19, SD = 0.6, range = 29-37 days). There were no differences in breeding pairs between the measurements of the first egg laid and successive eggs laid within a season. The proportion of light- and dark-colored chicks was 26% and 74%, respectively (N = 221) and differed from other Brown Noddy colonies studied in Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The length of time between clutches depended on whether the previous outcome was a failed clutch or a successfully fledged chick. Hatching, fledging, and reproductive success were significantly different between years. The subspecies (A. s. pihtus) differs in many aspects of its breeding biology from other colonies in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, in regard to year-round occurrence at the colony, frequent renesting attempts, large egg size, proportion of light and dark colored chicks, and low reproductive success caused by in- clement weather and predation by Great Frigatebirds (Fregata minor). Received 31 Mar., 1995, accepted 5 Dec. 1995. The Brown Noddy (Anous stolidus) is the largest and most widely distributed of the tropical and subtropical tern species (Cramp 1985). -

Noio Or Black Noddy Anous Minutus

Seabirds Noio or Black Noddy Anous minutus SPECIES STATUS: State recognized as Indigenous NatureServe Heritage Rank G5 - Secure North American Waterbird Conservation Plan – Photo: USFWS Moderate concern Regional Seabird Conservation Plan - USFWS 2005 SPECIES INFORMATION: The noio or black noddy is a medium-sized, abundant, and gregarious tern (Family: Laridae) with a pantropical distribution. Seven noio (black noddy) subspecies are generally recognized, and two are resident in Hawai‘i: A. s. melanogenys (MHI) and A. s. marcusi (NWHI). Individuals have slender wings, a wedge-shaped tail, and black bill which is slightly decurved. Adult males and females are sooty black with a white cap and have reddish brown legs and feet; bill droops slightly. Flight is swift with rapid wing beats and usually direct and low over the ocean; this species almost never soars high. Often forages in large, mixed species flocks associated with schools of large predatory fishes which drive prey species to the surface. Noio (black noddy) generally forage in nearshore waters and feeds mainly by dipping the surface from the wing or by making shallow dives. Opportunistic, in Hawai‘i, noio (black noddy) primarily takes juvenile goatfish, lizardfish, herring, flyingfish, and gobies. Nests in large, dense colonies that include non-breeding juvenile birds. Established pairs return to the same nest site year after year. Breeding is highly variable and egg laying occurs year-round. Both parents incubate single egg, and brood and feed chick. Birds first breed at two to three years of age, and the oldest known individual was 25 years old. DISTRIBUTION: Noio (black noddy) breed throughout the Hawaiian Archipelago, including all islands of NWHI and the coastal cliffs and offshore islets of MHI. -

Notes on the Birds Peculiar to Laysan Island, Hawaiian Group

3S4 V'lS,•ER,Birds of La),san Island. FL AukOct. NOTES ON THE BIRDS PECULIAR TO LAYSAN ISLAND, HAWAIIAN GROUP. 1 BY WALTER K. FISHER. •ølates x_,r_,r-x WE DOnot naturally associateland birds with tiny coral atolls in tropicalseas. It is thereforea strangefact that sucha diminu- tive island as Laysan, and one so remote from continentalshores, should harbor no less than five peculiar species: the Laysan Finch (]klespiza cantans) and Honey-eater (I-Iima•ione freethi), both • drepanidid' birds, the Miller Bird (.4crocefihalusfamiliaris), the LaysanRail (?orzanulapalmeri),and lastly the LaysanTeal (•tnas laysanensis).I usethe term ' land birds' loosely,in con- tradistinctionto sea-fowl,multitudes of which breed here through- out the year. The presenceof these speciesis all the more remarkablebecause none appear on neighboringislands, more or less distant, someof which are very similar to Laysan in structure and flora. Reachingout towardJapan from the main Hawaiian group is a long chainof volcanicrocks, atolls,sand-bars• and sunkenreefs, all insignificantin size and widely separated. The last islet is fully two thousandmiles from Honolulu and about half-way to Yokohama. Beginningat the east,the more importantmembers of this chain are: Bird Island and Necker (tall volcanicrocks), French Frigate Shoals, Gardner Rock, Laysan, Lisiansky, Mid- way, Cure, and Motell. Laysanis eighthundred miles northwest- by-westfrom Honolulu,and is perhapsbest knownas beingthe home of countless albatrosses. We sightedthe island early one morning in May, lying low on the horizon,with a great cloud of sea-birdshovering over it. On all sides the air was lively with terns, albatrosses,and boobies, •These notes were made during a visit of the Fish Commissionsteamer ' Albatross' to Laysan, May 17 to 23, 19o2, and are abridged from a more extendedreport on the avifauna of the i•land• to appearin the Bulletin of the U.S. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Black Noddy Subspecies Worcesteri

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.12 15 June 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE BLACK NODDY (Anous minutus) SUBSPECIES worcesteri ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Government of the Philippines has submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Black Noddy (Anous minutus) subspecies worcesteri on Appendix II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.12 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE BLACK NODDY (Anous minutus) SUBSPECIES worcesteri ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OFWILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL This proposal is for the inclusion of Black Noddy (Anous minutus) subspecies worcesteri in Appendix II. The species is classified as Endangered on account of a very small population which breeds within a tiny area of occupancy on just two islets, and is projected to decline by more than 70 per cent over the next 10 to 15 years. B. PROPONENT: Government of the Republic of the Philippines C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Aves 1.2 Order: Charadriiformes 1.3 Family: Laridae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Anous minutus worcesteri (McGregor, 1911) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: No known synonyms 1.6 Common name(s), in all applicable languages used by the Convention: English - Black Noddy French - Noddi noir Spanish - Tiñosa menuda 2. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Attention - Oahu Arborists Help Protect the Official Bird of Honolulu!

Attention - Oahu Arborists Help Protect the Official Bird of Honolulu! Look, Listen and Locate trees with nesting White terns. Do Not trim branches or remove trees with nesting White terns. Leave a nesting tree or branch alone for at least 80 days from when the egg is laid. Interesting Facts • White terns are found in urban Honolulu, especially in urban parks and residential areas from Hawaii Kai to Hickam Air Force Base. Nests may be found in other areas as well. • The White tern is also known as manu o Ku (the Hawaiian God Ku’s bird). • White terns are indigenous to Hawaii and lay a single egg directly on a ledge, tree branch, or other suitable location. • White terns can lay eggs anytime of the year, but most are laid from January through June. • A white tern egg will hatch after about 35 days of incubation. From the day an egg is laid it takes approximately 80 days for the chick to be mature enough to leave the nest on its own. The Law • Any action resulting in the killing or moving of a egg and/or chick, and the killing of an adult is prohibited under state and federal law. • Moving a chick to another branch is also a violation of state and federal law because it will result in abandonment of the chick by its parents. • Under Hawaii State law, the penalty for a first violation is a fine of not less than $250.00, imprisonment or both. In addi- tion, the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) may impose an administrative fine of up to $5,000.00 per specimen. -

Brown Noddy Anous Stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Bbrno Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM11010

Brown Noddy Anous stolidus Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bBRNO Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176941 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM11010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bBRNO.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bBRNO.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bBRNO Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bBRNO_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: --- NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), HI (SNR), LA (SNA), MS (SNA), NC (SNA), SC (SNA), TX (SNA) bBRNO Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. of Energy US Nat. Park Service NOAA Other Federal Lands ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Native Am.