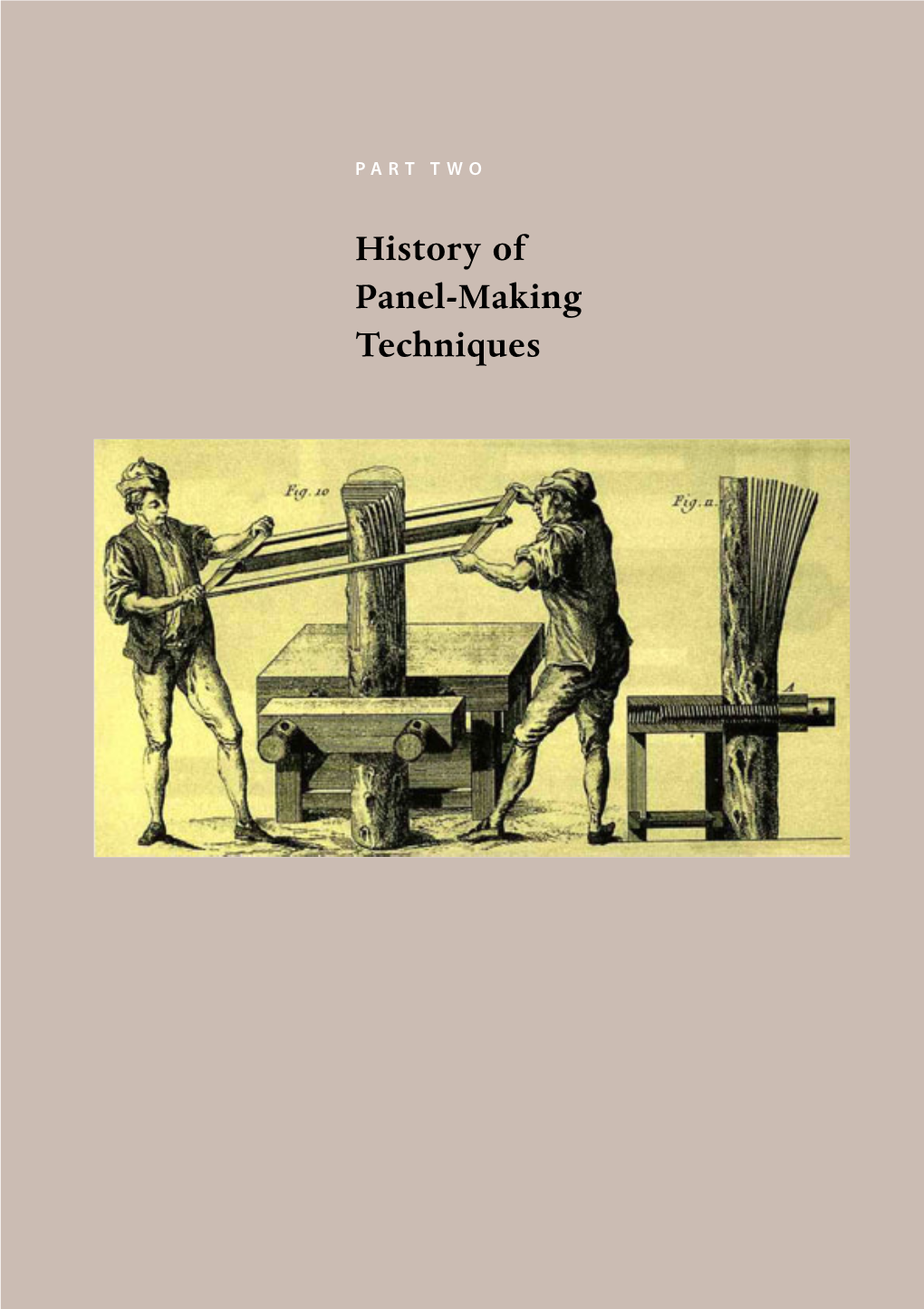

Historical Overview of Panel-Making Techniques in Central Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis and Strengthening of Carpentry Joints 1. Introduction 2

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software Branco, J.M., Descamps, T., Analysis and strengthening http://www.foxitsoftware.comof carpentry joints. Construction andFor Buildingevaluation Materials only. (2015), 97: 34–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.089 Analysis and strengthening of carpentry joints Jorge M. Branco Assistant Professor ISISE, Dept. Civil Eng., University of Minho Guimarães, Portugal Thierry Descamps Assistant Professor URBAINE, Dept. Structural Mech. and Civil Eng., University of Mons Mons, Belgium 1. Introduction Joints play a major role in the structural behaviour of old timber frames [1]. Current standards mainly focus on modern dowel-type joints and usually provide little guidance (with the exception of German and Swiss NAs) to designers regarding traditional joints. With few exceptions, see e.g. [2], [3], [4], most of the research undertaken today is mainly focused on the reinforcement of dowel-type connections. When considering old carpentry joints, it is neither realistic nor useful to try to describe the behaviour of each and every type of joint. The discussion here is not an extra attempt to classify or compare joint configurations [5], [6], [7]. Despite the existence of some classification rules which define different types of carpentry joints, their applicability becomes difficult. This is due to the differences in the way joints are fashioned depending, on the geographical location and their age. In view of this, it is mandatory to check the relevance of the calculations as a first step. This first step, to, is mandatory. A limited number of carpentry joints, along with some calculation rules and possible strengthening techniques are presented here. -

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850 Gallery 15

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 - 5 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. At this point in Domenichino’s career he wanted more commissions for narrative scenes and knew he needed to demonstrate his skill in depicting human action. -

Book of Abstracts: Studying Old Master Paintings

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE 1618 September 2009, Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London Supported by The Elizabeth Cayzer Charitable Trust STUDYING OLD MASTER PAINTINGS TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE THE NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN 30TH ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1618 September 2009 Sainsbury Wing Theatre, National Gallery, London The Proceedings of this Conference will be published by Archetype Publications, London in 2010 Contents Presentations Page Presentations (cont’d) Page The Paliotto by Guido da Siena from the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena 3 The rediscovery of sublimated arsenic sulphide pigments in painting 25 Marco Ciatti, Roberto Bellucci, Cecilia Frosinini, Linda Lucarelli, Luciano Sostegni, and polychromy: Applications of Raman microspectroscopy Camilla Fracassi, Carlo Lalli Günter Grundmann, Natalia Ivleva, Mark Richter, Heike Stege, Christoph Haisch Painting on parchment and panels: An exploration of Pacino di 5 The use of blue and green verditer in green colours in seventeenthcentury 27 Bonaguida’s technique Netherlandish painting practice Carole Namowicz, Catherine M. Schmidt, Christine Sciacca, Yvonne Szafran, Annelies van Loon, Lidwein Speleers Karen Trentelman, Nancy Turner Alterations in paintings: From noninvasive insitu assessment to 29 Technical similarities between mural painting and panel painting in 7 laboratory research the works of Giovanni da Milano: The Rinuccini -

Antonio Paolucci. Il Laico Che Custodisce I Tesori Del Papa

Trimestrale Data 06-2015 NUOVA ANTOLOGIA Pagina 178/82 Foglio 1 / 3 Italiani ANTONIO PAOLUCCI IL LAICO CHE CUSTODISCE I TESORI DEL PAPA Non e cambiato. All’imbrunire di una bella giornata d’inverno l’ho intravisto vicino al Pantheon. Si soffermava, osservava, scrutava gente e monumenti, come per anni gli avevo visto fare a Firenze, tra Palazzo Vecchio e Santa Croce. Si muoveva in modo dinoccolato, ma estremamente elegante e con autorevolezza. A Firenze il popolino e i bottegai lo salutavano con rispetto e con calore. A Roma, una frotta di turisti cinesi, senza sapere chi sia, gli fa spazio per farlo passare e il tono delle voci si abbassa. Ha un tratto e uno stile che lo distingue dagli altri, che lo fa notare. Dopo aver vissuto per anni a Firenze, Antonio Paolucci ora abita a Roma, ma ci sta da fi orentino. Cioè pronto a tornare sulle rive dell’Arno il venerdì sera e a riprendere il «Frecciarossa» il lunedì mattina. Dal 2007 lavora per l’ultimo monarca assoluto al mondo, che lo ha chiamato a curare una delle più importanti collezioni d’arte esistenti. La Bolla pontifi cia, fi rmata da Benedetto XVI, lo ha nominato, infatti, direttore dei Musei Vaticani. Paolucci considera questo incarico un «riconoscimento alla carriera». Un percorso lungo e glorioso per chi continua a defi nirsi un «tecnico della tutela». Classe 1939, nato a Rimini, nel 1969, dopo aver studiato a Firenze e Bologna, vince il concorso come ispettore delle Belle Arti. Inizia alla Soprintendenza di Firenze, poi nel 1980 diviene soprintendente di Venezia, quindi di Verona e di Mantova. -

ADB Staked Armchair

STAKED ARMCHAIR Chapter 2 Armbows are diff icult creatures. here’s something about building an armchair that tips the mental scales for many woodworkers. Making a stool is easy – it’s a board withT legs. OK, now take your stool and add a backrest to it. Congrats – you’ve made a backstool or perhaps a side chair. But once you add arms to that backstool you have committed a serious act of geometry. You’ve made an armchair, and that is hard-core angle business. Yes, armchairs are a little more complicated to build than stools or side chairs. But the geometry for the arms works the same way as it does for the legs or the spindles for the backrest. There are sightlines and re- sultant angles (if you need them). In fact, I would argue that adding arms to a chair simplifies the geometry because you have two points – the arm and the seat – to use to gauge the angle of your drill bit. When you drill legs, for example, you are alone in space. OK, I’m getting ahead of myself here. The key point is that arms are no big deal. So let’s talk about arms and how they should touch your back and your (surprise) arms. Staked Armchair all sticks are on 2-3/4" centers 2-3/4" 4-1/2" 3-1/2" 65° 38° 2-1/2" 2-1/2" CHAPTER II 27 Here. This is where I like the back of the armbow to go. Its inside edge lines up with the outside edge of the seat. -

Pad Foot Slipper Foot

PAD FOOT SLIPPER FOOT The most familiar foot of the To me, the slipper foot is the three, the pad foot has plenty most successful design for of variations. In the simplest the bottom of a cabriole leg, and most common version the especially when the arrises 3 rim of the foot is ⁄4 in. to 1 in. on the leg are retained and off the floor and its diameter gracefully end at the point is just under the size of the of the foot. There’s a blend leg blank. A competent 18th- of soft curves and defined century turner easily could edges that just works. This have produced it in less than particular foot design was 5 minutes, perhaps explaining taken from a Newport tea its prevalence. This is my table in the Pendleton House interpretation of a typical New collection at the Rhode Island England pad foot. School of Design Museum. 48 FINE WOODWORKING W270BR.indd 48 7/3/18 10:24 AM A step-by-step guide to creating three distinct period feet for the cabriole leg BY STEVE BROWN One Leg, Three Feet n the furniture making program at North Bennet Street School, students usually find inspiration for Itheir projects in books from our extensive library. They’ll find many examples of period pieces, but SLIPPER FOOT TRIFID FOOT they’ll also find more contemporary work. What they won’t find is any lack of possibilities. Sometimes limit- To me, the slipper foot is the The trifid foot is similar to the ing their options is the hard part. -

Fasteners Set the Industry's Highest Standards for Design, Ease of Use, and Reliability

Keeping your belt up and running SINCE 1907 HEAVY-DUTY MECHANICAL BELT FASTENING SYSTEMS A comprehensive line of mechanical belt fastening systems and belt conveyor maintenance tools that increase uptime and output. Around the world, the most respected name in belt conveyor solutions is Flexco. YOUR PARTNER IN The reason is simple. Flexco belt splicing products have earned the reputation for unsurpassed quality and performance in the most demanding material handling PRODUCTIVITY applications on earth. Our fasteners set the industry's highest standards for design, ease of use, and reliability. The knowledgeable advice and proven solutions we provide our customers help keep conveyor efficiency high and conveyor operation costs low. QUICK FACTS OVER 100 YEARS OF SUCCESS ABOUT FLEXCO • Flexco is a U.S.-based company and HAS BEEN BUILT has been in the belt industry since 1907. BY FOCUSING ON OUR • We have subsidiary locations in Australia, Chile, China, Germany, India, Mexico, Singapore, South Africa, and CUSTOMERS the United Kingdom to service and support customers in more than 150 countries around the world. We have learned to understand our customers' • We have more than 1800 distributor industries and challenges and to respond to their partners throughout the world—we changing needs. partner with the best distributors in We are constantly driving technology and design and every market we serve around the world to ensure our customers have strive to become the leader in belt conveyor solutions that ready access to our products, services, maximize uptime, productivity, and safety. and expert resources. We value industry relationships and believe that together, with a team of industry experts, our customers will • As a company, we focus on training and development and maintaining a receive greater value. -

TLJ Summer 2012

After a natural disaster strikes, getting back to normal may seem impossible. BEYOND WORDS SCHOOL LIBRARY RELIEF FUND Since 2006, the American Association of Sc Librarians, with funding from the Dollar Gen Foundation, has given more than $800,00 grants to over 90 school libraries across country affected by natural disasters. We’ve created a website with tools to help with o areas of the recovery proc Apply for a Beyond Words Grant: www.ala.org/aasl/disasterrelief American Association of School Librarians | 50 E Huron, Chicago, IL 60611 | 1-800-545-2433, ext 4382 | www.ala.org/aasl 499917_American.indd 1 11/4/10 11:15:36 PM TEXAS LIBRARY JOURNAL contents o After a natural Published by the Volume 88, N 2 Summer 2012 TEXAS LIBRARY disaster strikes, ASSOCIATION President’s Perspective ............................................................................... 63 Membership in TLA is open to any Sherilyn Bird individual or institution interested getting back in Texas libraries. Editorial: From the Ground Up .................................................................. 65 Gloria Meraz To find out more about TLA, order TLA to normal may publications, or place advertising in New Directions for the Association: The 2012-2015 TLA Strategic Plan Texas Library Journal, write to Texas Library Association Kathy Hoffman and Richard Wayne seem impossible. 3355 Bee Cave Road, Suite 401 Austin, Texas 78746-6763; Be Your Own Architect: Manage Renovation call 1-800-580-2TLA (2852); or visit Projects Internally – Part II .............................................................. 69 BEYOND WORDS SCHOOL LIBRARY RELIEF FUND our website at www.txla.org. Eric C. Shoaf Since 2006, the American Association of Sc A directory of TLA membership is Librarians, with funding from the Dollar Gen PR Branding Iron Awards .......................................................................... -

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam)

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Gabriel Metsu” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/gabriel- metsu/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Gabriel Metsu Page 2 of 5 Gabriel Metsu was born sometime in late 1629. His parents were the painter Jacques Metsu (ca. 1588–1629) and the midwife Jacquemijn Garniers (ca. 1590–1651).[1] Before settling in Leiden around 1615, Metsu’s father spent some time in Gouda, earning his living as a painter of patterns for tapestry manufacturers. No work by Jacques is known, nor do paintings attributed to him appear in Leiden inventories.[2] Both of Metsu’s parents came from Southwest Flanders, but when they were still children their families moved to the Dutch Republic. When the couple wed in Leiden in 1625, neither was young and both had previously been married. Jacquemijn’s second husband, Guilliam Fermout (d. ca. 1624) from Dordrecht, had also been a painter. Jacques Metsu never knew his son, for he died eight months before Metsu was born.[3] In 1636 his widow took a fourth husband, Cornelis Bontecraey (d. 1649), an inland water skipper with sufficient means to provide well for Metsu, as well as for his half-brother and two half-sisters—all three from Jacquemijn’s first marriage. -

The Circumcision

1969 Washington: no. 20. by 1669.2 Probably Isaak van den Blooken, the Netherlands, 1974 Hasselgren: in, 127, 131, 195, 198, no. G 53, by 1707; (sale, Amsterdam, 11 May 1707, no. 1). Duke of repro. Ancaster, by 1724;3 (sale, London, March 1724, no. 18); 1975 NGA: 284, 285, no. 77, repro. Andrew Hay; (sale, Cock, London, 14 February 1745, no. 1978 Bolten and Bolten-Rempt: 202, no. 549, repro. 47); John Spencer, 1st Earl of Spencer [1734-1783], Althorp 1984/1985 Schwartz: 339, no. 396, repro. (also 1985 House; inherited through family members to John Poyntz, English ed.). 5th Earl of Spencer [1835-1910]; (Arthur J. Sulley & Co., 1985 NGA: 330, repro. London); Peter A. B. Widener, Lynnewood Hall, Elkins 1986 Sutton: 314. Park, Pennsylvania, by 1912; inheritance from Estate of 1986 Tumpel: 413, no. 217, repro. Peter A. B. Widener by gift through power of appointment 1986 Guillaud and Guillaud: 362, no. 416, repro. of Joseph E. Widener, Elkins Park. 1990 The Hague: no. 53. Exhibited: Exhibition of Paintings, Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, 1868, no. 735. Rembrandt: Schilderijen Bijeengebracht ter Ge- lengenheid van de Inhuidiging van Hare Majesteit Koningin Wil- 1942.9.60 (656) helmina, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1898, no. 115. Winter Exhibition of Works by Rembrandt, Royal Academy, Lon don, 1899, no. 5. Washington 1969, no. 22. Rembrandt and the Rembrandt van Rijn Bible, Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 1987, no. 11. The Circumcision 1661 THE ONLY MENTION of the Circumcision of Christ Oil on canvas, 56.5 x 75 (22/4 x 29/2) occurs in the Gospel of Luke, 2:15-22: "...the Widener Collection shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even Inscriptions unto Bethlehem And they came with haste, and At lower right: Rembrandt, f 1661 found Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger— And when eight days were accomplished Technical Notes: The original support, a medium-weight, for the circumcising of the child, his name was called loosely woven, plain-weave fabric, has been lined with the tacking margins unevenly trimmed. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A.