Genome-Wide Data for Effective Conservation of Manta and Devil Ray Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuing Threat to Manta and Mobula Rays

Ţ Ţ Ţ ŢŢ Ţ :78;p8<Ţ Ţ\Ţ\Ţ Ţ \Ţ Ţi \Ţ Ţ Ţ 2 3 CONTENTS AT A GLANCE 4 2013 MARKET ESTIMATE 8 TOXICOLOGY AND USES 12 CONSUMER AWARENESS 14 STATUS AND TOURISM 16 CONSERVATION 20 REFERENCES AND PHOTO CREDITS 22 REPORT WRITERS Samantha Whitcraft, Mary O’Malley John Weller (graphics, design, editing) PROJECT TEAM Mary O’Malley – WildAid Paul Hilton – WildAid, Paul Hilton Photography Samantha Whitcraft – WildAid Daniel Fernando – The Manta Trust Shawn Heinrichs – WildAid, Blue Sphere Media 2013-14 MARKET SURVEYS, GUANGZHOU, CHINA ©2014 WILDAID 4 5 AT A GLANCE SUMMARY Manta and mobula rays, the mobulids, span the tropics of the world and are among the most captivating and charismatic of marine species. However, their the increasing demand for their gill plates, which are used as a pseudo-medicinala health tonic in China. To assess the trade in dried mobulid gill plates (product name ‘Peng Yu Sai’), and its potential impact on populations of these highly vulnerable species, WildAid researchers conducted market surveys throughout Southeast Asia in 2009-10.This research, compiled in our 2011 report The Global Threat to Manta and Mobula Rays(1), plate trade, representing over 99% of the market. In 2013, the same markets in and begin to gauge market trends. Dried gill plate samples were also purchased and tested for heavy metal contamination. Additionally, in 2014 two baseline complete understanding of Peng Yu Sai Our 2013 estimates reveal a market that has increased by 168% in value in only three years, representing a near threefold increase in mobulids taken, despite the listing of manta rays on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). -

Manta Or Mobula

IOTC-2010-WPEB-inf01 Draft identification guide IOTC Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB) Victoria, Seychelles 27-30 October, 2010 Mobulidae of the Indian Ocean: an identification hints for field sampling Draft, version 2.1, August 2010 by Romanov Evgeny(1)* (1) IRD, UMR 212 EME, Centre de Recherche Halieutique Mediterraneenne et Tropicale Avenue Jean Monnet – BP 171, 34203 Sete Cedex, France ([email protected]) * Present address: Project Leader. Project “PROSpection et habitat des grands PElagiques de la ZEE de La Réunion” (PROSPER), CAP RUN, ARDA, Magasin n°10, Port Ouest, 97420, Le Port, La Réunion, France. ABSTRACT Draft identification guide for species of Mobulidae family, which is commonly observed as by-catch in tuna associated fishery in the region is presented. INTRODUCTION Species of Mobulidae family are a common bycatch occurs in the pelagic tuna fisheries of the Indian Ocean both in the industrial (purse seine and longline) and artisanal (gillnets) sector (Romanov 2002; White et al., 2006; Romanov et al., 2008). Apparently these species also subject of overexploitation: most of Indian Ocean species marked as vulnerable or near threatened at the global level, however local assessment are often not exist (Table). Status of the species of the family Mobulidae in the Indian Ocean (IUCN, 2007) IUCN Status1 Species Common name Global status WIO EIO Manta birostris (Walbaum 1792) Giant manta NT - VU Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) Alfred manta - - - Mobula eregoodootenkee Longhorned - - - (Bleeker, 1859) mobula Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, Spinetail mobula NT - - 1841) Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, Shortfin devil ray NE - - 1841) Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, Chilean devil ray DD - VU 1892) Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908) Smoothtail NT - - mobula Lack of the data on the distribution, fisheries and biology of mobulids is often originated from the problem with specific identification of these species in the field. -

Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan2)

MALAYSIA NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARK (PLAN2) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRY MALAYSIA 2014 First Printing, 2014 Copyright Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Published in Malaysia by Department of Fisheries Malaysia Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia, Level 1-6, Wisma Tani Lot 4G2, Precinct 4, 62628 Putrajaya Malaysia Telephone No. : 603 88704000 Fax No. : 603 88891233 E-mail : [email protected] Website : http://dof.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-983-9819-99-1 This publication should be cited as follows: Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014. Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2), Ministry of Agriculture and Agro- based Industry Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia. 50pp SUMMARY Malaysia has been very supportive of the International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-SHARKS) developed by FAO that is to be implemented voluntarily by countries concerned. This led to the development of Malaysia’s own National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark or NPOA-Shark (Plan 1) in 2006. The successful development of Malaysia’s second National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2) is a manifestation of her renewed commitment to the continuous improvement of shark conservation and management measures in Malaysia. -

Lesser Devil Rays Mobula Cf. Hypostoma from Venezuela Are Almost Twice Their Previously Reported Maximum Size and May Be a New Sub-Species

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 90, 1142–1148 doi:10.1111/jfb.13252, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma from Venezuela are almost twice their previously reported maximum size and may be a new sub-species N. R. Ehemann*†‡§, L. V. González-González*† and A. W. Trites‖ *Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Apartado Postal 592, La Paz, Baja California Sur C.P. 23000, Mexico, †Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas del Mar (ECAM), Boca del Río, Universidad de Oriente, Núcleo Nueva Esparta (UDONE), Boca del Río, Nueva Esparta, C.P. 06304, Venezuela, ‡Proyecto Iniciativa Batoideos (PROVITA), Caracas, Venezuela and ‖Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada (Received 8 September 2016, Accepted 23 November 2016) Three rays opportunistically obtained near Margarita Island, Venezuela, were identified as lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma, but their disc widths were between 207 and 230 cm, which is almost dou- ble the reported maximum disc width of 120 cm for this species. These morphometric data suggest that lesser devil rays are either larger than previously recognized or that these specimens belong to an unknown sub-species of Mobula in the Caribbean Sea. Better data are needed to describe the distribu- tion, phenotypic variation and population structure of this poorly known species. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: batoids; by-catch; Caribbean Sea; Chondrichthyes; Myliobatiformes. There is limited biological and fisheries information about the body size at maturity, population size, stock, maximum age and length–mass relationships of Mobula hypos- toma (Bancroft, 1831), better known as the lesser devil ray. -

First Record of Mobula Japonica (Muller Et Hentle), a Little Known Devil Ray from the Gulf of Thailand (Pisces : Mobulidae)

FIRST RECORD OF MOBULA JAPONICA (MULLER ET HENTLE), A LITTLE KNOWN DEVIL RAY FROM THE GULF OF THAILAND (PISCES : MOBULIDAE) Thosaporn Wongratana* Abstract A specimen of young Mobulajaponica (Muller & Henle), measured 661 rom across wings, is here described together with a note on the sight ing of 12 big specimens from Koh Chang, Trat Province, in the Gulf of Thailand. This is the first documentary report of the family Mobulidae for Thailand and of. the species for the South China Sea. Previously, the species were occasionally recorded from Japan, Honolulu, Samoa, Korea and Taiwan waters. Its inferior mouth with a band of teeth in both jaws, the very long whip-liked tail, and a prominent serrated caudal spine pro vide the main distinct characteristics and separate it from other related species. The full measurements of this young specimen and of the Naga Expedition's specimen of Mobula diabolus (Shaw), taken from Cambodian water, are also given. Introduction Jn order to update the knowledge of marine fish fauna of Thailand, regular observation of fish landing and occasional procurement of fish specimens are made at the Bangkok Wholesale Fish Market, operated by the Fish Marketing Organization of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. On 4 December 1973, the author came across a young devil ray or sea devil, known in Thai "Pia rahu" (uom»). The fish measured 661 mm across the width. He has no hesitati~ns to make a further look for other specimens. And this led him to spot other 8 big males and 3 females of about the same size. -

CONCERTED ACTION for the MOBULID RAYS (MOBULIDAE)1 Adopted by the Conference of the Parties at Its 13Th Meeting (Gandhinagar, February 2020)

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/Concerted Action 12.6 (Rev.COP13) MIGRATORY Original: English SPECIES CONCERTED ACTION FOR THE MOBULID RAYS (MOBULIDAE)1 Adopted by the Conference of the Parties at its 13th Meeting (Gandhinagar, February 2020) The Concerted Action for Mobulid Rays was first adopted at the 12th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (UNEP/CMS/COP12/Concerted Action 12.6). A report on implementation was submitted to the 13th Meeting of the Parties (COP13) together with a proposal for extension and revision (UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.28.1.6), which was approved by the Parties. (i). Proponents: The Manta Trust The Manta Trust is an international organization that takes a multidisciplinary approach to the conservation of Manta spp. and Mobula spp. Mobulid rays and their habitats through conducting robust science and research, raising awareness and educating the general public and community stakeholders. The Manta Trust network extends across the globe, including collaborations and affiliated projects in over 25 countries and mobulid Range States. The Manta Trust is a Cooperating Partner to the CMS Sharks MOU. Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) The Wildlife Conservation Society is an international conservation organization working to save wildlife and wild places worldwide through science, conservation action, education, and inspiring people to value nature. WCS works across the globe in more than 60 countries, and the WCS Marine Conservation Program works in more than 20 countries to protect key marine habitats and wildlife, end overfishing, and protect key species, including sharks and rays. WCS is a founding partner of the Global Sharks and Rays Initiative (GSRI), which is implementing a global ten-year strategy that aims to: save shark and ray species from extinction; transition shark and ray fisheries to sustainability; effectively control international trade in shark and ray parts and products; and reduce consumption of shark and ray products from illegal or unsustainable sources. -

Evolution and Functional Morphology of the Cephalic Lobes in Batoids Samantha Lynn Mulvany University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 12-11-2013 Evolution and Functional Morphology of the Cephalic Lobes in Batoids Samantha Lynn Mulvany University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Anatomy Commons, Biology Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Mulvany, Samantha Lynn, "Evolution and Functional Morphology of the Cephalic Lobes in Batoids" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5083 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evolution and Functional Morphology of the Cephalic Lobes in Batoids by Samantha Lynn Mulvany A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Integrative Biology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Philip J. Motta, Ph.D. Stephen M. Deban, Ph.D. Henry R. Mushinsky, Ph.D. Jason R. Rohr, Ph.D. Date of Approval: December 11, 2013 Keywords: Novel Structure, Modulation, Independent Contrast, Anatomy Copyright © 2014, Samantha Lynn Mulvany DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this to my family and friends. My family has always been very supportive of my academic endeavors, nurturing my love of biology from early childhood to this very day. My grandfather, who passed away on the day that I was accepted into the program, has been with me every step of the way on this bittersweet journey. -

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives Guy Mark William Stevens Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment August 2016 2 Abstract This multi-decade study on an isolated and unfished population of manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris) in the Maldives used individual-based photo-ID records and behavioural observations to investigate the world’s largest known population of M. alfredi and a previously unstudied population of M. birostris. This research advances knowledge of key life history traits, reproductive strategies, population demographics and habitat use of M. alfredi, and elucidates the feeding and mating behaviour of both manta species. M. alfredi reproductive activity was found to vary considerably among years and appeared related to variability in abundance of the manta’s planktonic food, which in turn may be linked to large-scale weather patterns such as the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Key to helping improve conservation efforts of M. alfredi was my finding that age at maturity for both females and males, estimated at 15 and 11 years respectively, appears up to 7 – 8 years higher respectively than previously reported. As the fecundity of this species, estimated at one pup every 7.3 years, also appeared two to more than three times lower than estimates from studies with more limited data, my work now marks M. alfredi as one of the world’s least fecund vertebrates. With such low fecundity and long maturation, M. alfredi are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and therefore needs complete protection from exploitation across its entire global range. -

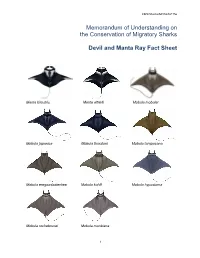

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Elasmobranchs (Sharks and Rays): a Review of Status, Distribution and Interaction with Fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/277329893 Elasmobranchs (sharks and rays): a review of status, distribution and interaction with fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean CHAPTER · JANUARY 2015 READS 81 2 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Jeremy J Kiszka Florida International University 52 PUBLICATIONS 389 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Jeremy J Kiszka Retrieved on: 16 October 2015 OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Special Publication No. 10 Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) The Investigational Report series of the Oceanographic Research Institute presents the detailed results of marine biological research. Reports have appeared at irregular intervals since 1961. All manuscripts are submitted for peer review. The Special Publication series of the Oceanographic Research Institute reports on expeditions, surveys and workshops, or provides bibliographic and technical information. The series appears at irregular intervals. The Bulletin series of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research is of general interest and reviews the research and curatorial activities of the Oceanographic Research Institute, uShaka Sea World and the Sea World Education Centre. It is published annually. These series are available in exchange for relevant publications of other scientific institutions anywhere in the world. All correspondence in this regard should be directed to: The Librarian Oceanographic Research Institute PO Box 10712 Marine Parade 4056 Durban, South Africa OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) South African Association for Marine Biological Research Oceanographic Research Institute Special Publication No. -

Ins Stitut to Pol Litécn Nico N Nacion

INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO NACIONAL CENTRO INTERDISCIPLINARIO DE CIENCIAS MARINAS ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DE LA REPRODUCCIÓN DE TRES ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO MOBULA (CHONDRICHTHYES: MOBULIDAE) EN EL SUROESTE DEL GOLFO DE CALIFORNIA, MÉXICO TESIS QUE PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRÍA EN CIENCIAS EN MANEJO DE RECURSOS MARINOS PRESENTA JAVIER NOE SERRANO LÓPEZ LA PAZ, B. C. S., MÉXICO a 10 de Diciembre de 2009 GLOSARIO Ciclo gonádico: Evento periódico que tiene lugar en las gónadas y conduce a la producción de gametos. Ciclo Ovárico: Estadios de desarrollo en serie por los que atraviesa la gónada femenina y abarca desde una etapa de recuperación o reposo hasta el siguiente desove. Ciclo reproductivo: Evento periódico en el que las gónadas producen gametos y los organismos se reproducen. Cigoto: Célula diploide que resulta de la fusión de los gametos masculino y femenino (Curtis et.al., 2001). Chondrichthyes: Clase de peces cartilaginosos que abarcan tiburones, rayas y quimeras (Nelson, 2004). Cromosoma: Orgánulo en el núcleo celular considerado como la estructura que contienen a los genes (Curtis et.al., 2001). Diamétrico.- Tipo de zonación en elasmobranquios donde la espermatogenesis sigue un gradiente de desarrollo que corre a lo largo del diámetro testicular (Pratt, 1998). Elasmobranquios: Peces cartilaginosos ubicados en la clase Chondrichthyes subclase Elasmobranchii que abarca tiburones, rayas, mantarrayas y otros peces cartilaginosos (Nelson, 2004). Espermatogónia: Células diploides no especializadas ubicadas en las paredes de los testículos que por división meiótica darán origen a espermatocitos (Curtis et.al., 2001). Espermatocito: Es la célula germinal masculina que se encuentra en proceso de maduración (Lender et al., 1982). Espermatogenesis. Proliferación de células germinales masculinas a partir de la división mitótica de las espermatogónias (Curtis et.al., 2001). -

Mobula Munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Description of frst nursery area for a pygmy devil ray species (Mobula munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D. Palacios1,2, Edgar M. Hoyos‑Padilla2,4, Abel Trejo‑Ramírez2, Donald A. Croll3, Felipe Galván‑Magaña1, Kelly M. Zilliacus3, John B. O’Sullivan5, James T. Ketchum2,6 & Rogelio González‑Armas1* Munk’s pygmy devil rays (Mobula munkiana) are medium‑size, zooplanktivorous flter feeding, elasmobranchs characterized by aggregative behavior, low fecundity and delayed reproduction. These traits make them susceptible to targeted and by‑catch fsheries and are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Multiple studies have examined fsheries impacts, but nursery areas or foraging neonate and juvenile concentrations have not been examined. This study describes the frst nursery area for M. munkiana at Espiritu Santo Archipelago, Mexico. We examined spatial use of a shallow bay during 22 consecutive months in relation to environmental patterns using traditional tagging (n = 95) and acoustic telemetry (n = 7). Neonates and juveniles comprised 84% of tagged individuals and their residency index was signifcantly greater inside than outside the bay; spending a maximum of 145 consecutive days within the bay. Observations of near‑term pregnant females, mating behavior, and neonates indicate an April to June pupping period. Anecdotal photograph review indicated that the nursery area is used by neonates and juveniles across years. These fndings confrm, for the frst time, the existence of nursery areas for Munk’s pygmy devil rays and the potential importance of shallow bays during early life stages for the conservation of this species. Nursery areas have been shown to be important for many elasmobranch species 1,2.