Devils in Distress: the Plight of Mobula Rays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manta Or Mobula

IOTC-2010-WPEB-inf01 Draft identification guide IOTC Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB) Victoria, Seychelles 27-30 October, 2010 Mobulidae of the Indian Ocean: an identification hints for field sampling Draft, version 2.1, August 2010 by Romanov Evgeny(1)* (1) IRD, UMR 212 EME, Centre de Recherche Halieutique Mediterraneenne et Tropicale Avenue Jean Monnet – BP 171, 34203 Sete Cedex, France ([email protected]) * Present address: Project Leader. Project “PROSpection et habitat des grands PElagiques de la ZEE de La Réunion” (PROSPER), CAP RUN, ARDA, Magasin n°10, Port Ouest, 97420, Le Port, La Réunion, France. ABSTRACT Draft identification guide for species of Mobulidae family, which is commonly observed as by-catch in tuna associated fishery in the region is presented. INTRODUCTION Species of Mobulidae family are a common bycatch occurs in the pelagic tuna fisheries of the Indian Ocean both in the industrial (purse seine and longline) and artisanal (gillnets) sector (Romanov 2002; White et al., 2006; Romanov et al., 2008). Apparently these species also subject of overexploitation: most of Indian Ocean species marked as vulnerable or near threatened at the global level, however local assessment are often not exist (Table). Status of the species of the family Mobulidae in the Indian Ocean (IUCN, 2007) IUCN Status1 Species Common name Global status WIO EIO Manta birostris (Walbaum 1792) Giant manta NT - VU Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) Alfred manta - - - Mobula eregoodootenkee Longhorned - - - (Bleeker, 1859) mobula Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, Spinetail mobula NT - - 1841) Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, Shortfin devil ray NE - - 1841) Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, Chilean devil ray DD - VU 1892) Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908) Smoothtail NT - - mobula Lack of the data on the distribution, fisheries and biology of mobulids is often originated from the problem with specific identification of these species in the field. -

Occurrence of Devil Rays (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae)

Scientific Note Record of a pregnant Mobula thurstoni and occurrence of Manta birostris (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae) in the vicinity of Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago (Equatorial Atlantic) 1, 2* 1 1 SIBELE A. MENDONÇA , BRUNO C. L. MACENA , EMMANUELLY CREIO , DANIELLE 1, 2 1 1 L. VIANA , DANIEL F. VIANA & FABIO. H. V. HAZIN 1Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, UFRPE Laboratório de Oceanografia Pesqueira, LOP/Departamento de Pesca e Aqüicultura, DEPAq/. Av. Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, campus universitário, Dois Irmãos. CEP- 52171-900 Recife, PE, Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, UFPE, Cidade Universitária, Departamento de Oceanografia, Recife, PE, Brasil. *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this study, the occurrence of a pregnant Mobula thurstoni and six specimens of Manta birostris from the Archipelago of St. Peter and St. Paul were recorded for the first time. The description of morphology and morphometrics of the embryo of M. thurstoni was also reported. Keywords: oceanic island, chondrichthyes, elasmobranchii, devil rays, pelagic animal Resumo. Registro de Mobula thurstoni prenhe e ocorrência de Manta birostris (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae) no entorno do Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo (Atlântico Equatorial). No presente trabalho, as ocorrências de uma Mobula thurstoni prenhe e de seis espécimes de Manta birostris no Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo foram registradas pela primeira vez. A descrição morfológica e os dados morfométricos do embrião de M. thurstoni foram igualmente reportados. Palavras chave: ilha oceânica, chondrichthyes, elasmobranchii, raias manta, animais pelágicos The Mobulidae family is composed of 11 latter, four species were recorded in the vicinity of species and two genera: Manta and Mobula and is the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago (SPSPA; found typically in waters rich in secondary 00°55’N, 29°21’W); M. -

Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan2)

MALAYSIA NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARK (PLAN2) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRY MALAYSIA 2014 First Printing, 2014 Copyright Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Published in Malaysia by Department of Fisheries Malaysia Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia, Level 1-6, Wisma Tani Lot 4G2, Precinct 4, 62628 Putrajaya Malaysia Telephone No. : 603 88704000 Fax No. : 603 88891233 E-mail : [email protected] Website : http://dof.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-983-9819-99-1 This publication should be cited as follows: Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014. Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2), Ministry of Agriculture and Agro- based Industry Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia. 50pp SUMMARY Malaysia has been very supportive of the International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-SHARKS) developed by FAO that is to be implemented voluntarily by countries concerned. This led to the development of Malaysia’s own National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark or NPOA-Shark (Plan 1) in 2006. The successful development of Malaysia’s second National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2) is a manifestation of her renewed commitment to the continuous improvement of shark conservation and management measures in Malaysia. -

West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA Bicc)

Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC) SCOPING STUDY ON ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION AND TRADE DELIVERABLE N°6: FINAL SCOPING REPORT ON “ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION, AND TRADE” Email: [email protected] Tel.: +225 44 02 19 17 (Côte d’Ivoire) / +32 495 496 007 (Belgium) Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization Table of content 1. Categorization of the issue ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Chondrichthyans ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1. sharks, rays excluded .......................................................................................................................... 3 a) Status ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2. Rays ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 a) Status ..................................................................................................................................................... -

First Record of Mobula Japonica (Muller Et Hentle), a Little Known Devil Ray from the Gulf of Thailand (Pisces : Mobulidae)

FIRST RECORD OF MOBULA JAPONICA (MULLER ET HENTLE), A LITTLE KNOWN DEVIL RAY FROM THE GULF OF THAILAND (PISCES : MOBULIDAE) Thosaporn Wongratana* Abstract A specimen of young Mobulajaponica (Muller & Henle), measured 661 rom across wings, is here described together with a note on the sight ing of 12 big specimens from Koh Chang, Trat Province, in the Gulf of Thailand. This is the first documentary report of the family Mobulidae for Thailand and of. the species for the South China Sea. Previously, the species were occasionally recorded from Japan, Honolulu, Samoa, Korea and Taiwan waters. Its inferior mouth with a band of teeth in both jaws, the very long whip-liked tail, and a prominent serrated caudal spine pro vide the main distinct characteristics and separate it from other related species. The full measurements of this young specimen and of the Naga Expedition's specimen of Mobula diabolus (Shaw), taken from Cambodian water, are also given. Introduction Jn order to update the knowledge of marine fish fauna of Thailand, regular observation of fish landing and occasional procurement of fish specimens are made at the Bangkok Wholesale Fish Market, operated by the Fish Marketing Organization of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. On 4 December 1973, the author came across a young devil ray or sea devil, known in Thai "Pia rahu" (uom»). The fish measured 661 mm across the width. He has no hesitati~ns to make a further look for other specimens. And this led him to spot other 8 big males and 3 females of about the same size. -

GENUS Mobula) in CMS APPENDIX I and II

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/ScC18/Doc.7.2.10 MIGRATORY 11 June 2014 SPECIES Original: English 18th MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 1-3 July 2014 Agenda Item 7.2 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ALL SPECIES OF MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) IN CMS APPENDIX I AND II Summary The Government of Fiji has submitted a proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in CMS Appendix I th and II at the 11 Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP11), 4-9 November 2014, Quito, Ecuador. An advanced unedited version of the proposal, as received from the proponent Party, is reproduced under this cover for its early consideration by the Scientific Council. It will be replaced by the final version as soon as possible. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/ScC18/Doc.7.2.10: Proposal I/10 & II/11 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in Appendix I and II B. PROPONENT: Government of Fiji C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1. Taxon 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Rajiformes 1.3 Subfamily: Mobulinae 1.4 Genus and species: All nine species within the Genus Mobula (Rafinesque, 1810): Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788), Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908), Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, 1892), Mobula eregoodootenkee (Bleeker, 1859),Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula hypostoma (Bancroft, 1831), Mobula rochebrunei (Vaillant, 1879), Mobula munkiana (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987) and any other putative Mobula species. -

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

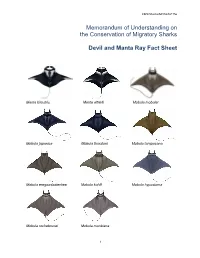

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Elasmobranchs (Sharks and Rays): a Review of Status, Distribution and Interaction with Fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/277329893 Elasmobranchs (sharks and rays): a review of status, distribution and interaction with fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean CHAPTER · JANUARY 2015 READS 81 2 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Jeremy J Kiszka Florida International University 52 PUBLICATIONS 389 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Jeremy J Kiszka Retrieved on: 16 October 2015 OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Special Publication No. 10 Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) The Investigational Report series of the Oceanographic Research Institute presents the detailed results of marine biological research. Reports have appeared at irregular intervals since 1961. All manuscripts are submitted for peer review. The Special Publication series of the Oceanographic Research Institute reports on expeditions, surveys and workshops, or provides bibliographic and technical information. The series appears at irregular intervals. The Bulletin series of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research is of general interest and reviews the research and curatorial activities of the Oceanographic Research Institute, uShaka Sea World and the Sea World Education Centre. It is published annually. These series are available in exchange for relevant publications of other scientific institutions anywhere in the world. All correspondence in this regard should be directed to: The Librarian Oceanographic Research Institute PO Box 10712 Marine Parade 4056 Durban, South Africa OFFSHORE FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHWEST INDIAN OCEAN: their status and the impact on vulnerable species Rudy van der Elst and Bernadine Everett (editors) South African Association for Marine Biological Research Oceanographic Research Institute Special Publication No. -

Assessing Sharks and Rays in Shallow Coastal Habitats Using Baited

Assessing sharks and rays in shallow coastal habitats using baited underwater video and aerial surveys in the Red Sea Thesis by Ashlie J. McIvor In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Thuwal, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia May, 2020 2 EXAMINATION COMMITTEE PAGE The thesis of Ashlie Jane McIvor is approved by the examination committee. Committee Chairperson: Prof. Michael Berumen Committee Members: Prof. Burton Jones, Dr. Darren Coker, Dr. Julia Spaet [external] 3 © May, 2020 Ashlie J. McIvor All Rights Reserved 4 ABSTRACT Years of unregulated fishing activity have resulted in low abundances of elasmobranch species in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Coastal populations of sharks and rays in the region remain largely understudied and may be at risk from large-scale coastal development projects. Here we aim to address this pressing need for information by using fish market, unmanned aerial vehicle and baited remote underwater video surveys to quantify the abundance and diversity of sharks and rays in coastal habitats in the Saudi Arabian central Red Sea. Our analysis showed that the majority of observed individuals were batoids, specifically blue-spotted ribbontail stingrays (Taeniura lymma) and reticulate whiprays (Himantura sp.). Aerial surveys observed a catch per unit effort two orders of magnitude greater than underwater video surveys, yet did not detect any shark species. In contrast, baited camera surveys observed both lemon sharks (Negaprion acutidens) and tawny nurse sharks (Nebrius ferrugineus), but in very low quantities (one individual of each species). The combination of survey techniques revealed a higher diversity of elasmobranch presence than using either method alone, however many species of elasmobranch known to exist in the Red Sea were not detected. -

Mobula Munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Description of frst nursery area for a pygmy devil ray species (Mobula munkiana) in the Gulf of California, Mexico Marta D. Palacios1,2, Edgar M. Hoyos‑Padilla2,4, Abel Trejo‑Ramírez2, Donald A. Croll3, Felipe Galván‑Magaña1, Kelly M. Zilliacus3, John B. O’Sullivan5, James T. Ketchum2,6 & Rogelio González‑Armas1* Munk’s pygmy devil rays (Mobula munkiana) are medium‑size, zooplanktivorous flter feeding, elasmobranchs characterized by aggregative behavior, low fecundity and delayed reproduction. These traits make them susceptible to targeted and by‑catch fsheries and are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Multiple studies have examined fsheries impacts, but nursery areas or foraging neonate and juvenile concentrations have not been examined. This study describes the frst nursery area for M. munkiana at Espiritu Santo Archipelago, Mexico. We examined spatial use of a shallow bay during 22 consecutive months in relation to environmental patterns using traditional tagging (n = 95) and acoustic telemetry (n = 7). Neonates and juveniles comprised 84% of tagged individuals and their residency index was signifcantly greater inside than outside the bay; spending a maximum of 145 consecutive days within the bay. Observations of near‑term pregnant females, mating behavior, and neonates indicate an April to June pupping period. Anecdotal photograph review indicated that the nursery area is used by neonates and juveniles across years. These fndings confrm, for the frst time, the existence of nursery areas for Munk’s pygmy devil rays and the potential importance of shallow bays during early life stages for the conservation of this species. Nursery areas have been shown to be important for many elasmobranch species 1,2. -

MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) in CMS APPENDIX I and II

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/ MIGRATORY Rev.1 4 November 2014 SPECIES Original: English 11th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Quito, Ecuador, 4-9 November 2014 Agenda Item 24.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ALL SPECIES OF MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) IN CMS APPENDIX I AND II Summary: The Government of Fiji has submitted a proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in CMS Appendix I and II at the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP11), 4-9 November 2014, Quito, Ecuador. A revised proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula Rays (Mobula) in CMS Appendices I and II was subsequently submitted by Fiji pursuant to Rule 11 of the COP Rules of Procedure. The proposal is reproduced under this cover for a decision on its approval or rejection by the Conference of the Parties. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the Meeting. Delegates are requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/Rev.1: Proposal I/10 & II/11 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in Appendix I and II B. PROPONENT: Government of Fiji C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1. Taxon 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Rajiformes 1.3 Subfamily: Mobulinae 1.4 Genus and species: All nine species within the Genus Mobula (Rafinesque, 1810): Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788), Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908), Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, 1892), Mobula eregoodootenkee (Bleeker, 1859),Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula hypostoma (Bancroft, 1831), Mobula rochebrunei (Vaillant, 1879), Mobula munkiana (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987) and any other putative Mobula species. -

A Conservation Strategy for Devil and Manta Rays

1 Sympathy for the devil: A conservation strategy for devil and manta rays 2 3 Julia M. Lawson1*, Rachel H.L. Walls1, Sonja V. Fordham 2, Mary P. O’Malley3,4, Michelle 4 R. Heupel5, Guy Stevens 4,6, Daniel Fernando4,6,7, Ania Budziak8, Colin A. Simpfendorfer 9, 5 Lindsay N.K. Davidson1, Isabel Ender4, Malcolm P. Francis11, Giuseppe Notarbartolo di 6 Sciara12, and Nicholas K. Dulvy 1 7 8 1 Earth to Ocean Research Group, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, 9 Burnaby, BC, Canada 10 2 Shark Advocates International, The Ocean Foundation, Washington, DC, USA 11 3 WildAid, San Francisco, CA, USA 12 4 Manta Trust, Dorchester, Dorset, UK 13 5 Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Queensland, Australia 14 6 Environment Department, University of York, UK 15 6 Department of Biology and Environmental Science, Linnaeus University, 39182 Kalmar, 16 Sweden 17 7 Blue Resources, Colombo, Sri Lanka 18 8 Project AWARE Foundation, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA 19 9 Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture & College of Marine and 20 Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia 21 11 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901, Wellington 6241, 22 New Zealand 23 12 Tethys Research Institute, Viale G.B. Gadio 2, 20121, Milano, Italy 1 PeerJ PrePrints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.1731v1 | CC-BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 9 Feb 2016, publ: 9 Feb 2016 24 Corresponding Author: 25 Julia M Lawson1 26 Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, British Columbia, V5A 1S6, Canada 27 Email address: [email protected] 28 2 PeerJ PrePrints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.1731v1 | CC-BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 9 Feb 2016, publ: 9 Feb 2016 29 Abstract 30 31 Background.