A Conservation Strategy for Devil and Manta Rays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manta Or Mobula

IOTC-2010-WPEB-inf01 Draft identification guide IOTC Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB) Victoria, Seychelles 27-30 October, 2010 Mobulidae of the Indian Ocean: an identification hints for field sampling Draft, version 2.1, August 2010 by Romanov Evgeny(1)* (1) IRD, UMR 212 EME, Centre de Recherche Halieutique Mediterraneenne et Tropicale Avenue Jean Monnet – BP 171, 34203 Sete Cedex, France ([email protected]) * Present address: Project Leader. Project “PROSpection et habitat des grands PElagiques de la ZEE de La Réunion” (PROSPER), CAP RUN, ARDA, Magasin n°10, Port Ouest, 97420, Le Port, La Réunion, France. ABSTRACT Draft identification guide for species of Mobulidae family, which is commonly observed as by-catch in tuna associated fishery in the region is presented. INTRODUCTION Species of Mobulidae family are a common bycatch occurs in the pelagic tuna fisheries of the Indian Ocean both in the industrial (purse seine and longline) and artisanal (gillnets) sector (Romanov 2002; White et al., 2006; Romanov et al., 2008). Apparently these species also subject of overexploitation: most of Indian Ocean species marked as vulnerable or near threatened at the global level, however local assessment are often not exist (Table). Status of the species of the family Mobulidae in the Indian Ocean (IUCN, 2007) IUCN Status1 Species Common name Global status WIO EIO Manta birostris (Walbaum 1792) Giant manta NT - VU Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) Alfred manta - - - Mobula eregoodootenkee Longhorned - - - (Bleeker, 1859) mobula Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, Spinetail mobula NT - - 1841) Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, Shortfin devil ray NE - - 1841) Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, Chilean devil ray DD - VU 1892) Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908) Smoothtail NT - - mobula Lack of the data on the distribution, fisheries and biology of mobulids is often originated from the problem with specific identification of these species in the field. -

Occurrence of Devil Rays (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae)

Scientific Note Record of a pregnant Mobula thurstoni and occurrence of Manta birostris (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae) in the vicinity of Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago (Equatorial Atlantic) 1, 2* 1 1 SIBELE A. MENDONÇA , BRUNO C. L. MACENA , EMMANUELLY CREIO , DANIELLE 1, 2 1 1 L. VIANA , DANIEL F. VIANA & FABIO. H. V. HAZIN 1Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, UFRPE Laboratório de Oceanografia Pesqueira, LOP/Departamento de Pesca e Aqüicultura, DEPAq/. Av. Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, campus universitário, Dois Irmãos. CEP- 52171-900 Recife, PE, Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, UFPE, Cidade Universitária, Departamento de Oceanografia, Recife, PE, Brasil. *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this study, the occurrence of a pregnant Mobula thurstoni and six specimens of Manta birostris from the Archipelago of St. Peter and St. Paul were recorded for the first time. The description of morphology and morphometrics of the embryo of M. thurstoni was also reported. Keywords: oceanic island, chondrichthyes, elasmobranchii, devil rays, pelagic animal Resumo. Registro de Mobula thurstoni prenhe e ocorrência de Manta birostris (Myliobatiformes: Mobulidae) no entorno do Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo (Atlântico Equatorial). No presente trabalho, as ocorrências de uma Mobula thurstoni prenhe e de seis espécimes de Manta birostris no Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo foram registradas pela primeira vez. A descrição morfológica e os dados morfométricos do embrião de M. thurstoni foram igualmente reportados. Palavras chave: ilha oceânica, chondrichthyes, elasmobranchii, raias manta, animais pelágicos The Mobulidae family is composed of 11 latter, four species were recorded in the vicinity of species and two genera: Manta and Mobula and is the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago (SPSPA; found typically in waters rich in secondary 00°55’N, 29°21’W); M. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Lesser Devil Rays Mobula Cf. Hypostoma from Venezuela Are Almost Twice Their Previously Reported Maximum Size and May Be a New Sub-Species

Journal of Fish Biology (2017) 90, 1142–1148 doi:10.1111/jfb.13252, available online at wileyonlinelibrary.com Lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma from Venezuela are almost twice their previously reported maximum size and may be a new sub-species N. R. Ehemann*†‡§, L. V. González-González*† and A. W. Trites‖ *Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Apartado Postal 592, La Paz, Baja California Sur C.P. 23000, Mexico, †Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas del Mar (ECAM), Boca del Río, Universidad de Oriente, Núcleo Nueva Esparta (UDONE), Boca del Río, Nueva Esparta, C.P. 06304, Venezuela, ‡Proyecto Iniciativa Batoideos (PROVITA), Caracas, Venezuela and ‖Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada (Received 8 September 2016, Accepted 23 November 2016) Three rays opportunistically obtained near Margarita Island, Venezuela, were identified as lesser devil rays Mobula cf. hypostoma, but their disc widths were between 207 and 230 cm, which is almost dou- ble the reported maximum disc width of 120 cm for this species. These morphometric data suggest that lesser devil rays are either larger than previously recognized or that these specimens belong to an unknown sub-species of Mobula in the Caribbean Sea. Better data are needed to describe the distribu- tion, phenotypic variation and population structure of this poorly known species. © 2017 The Fisheries Society of the British Isles Key words: batoids; by-catch; Caribbean Sea; Chondrichthyes; Myliobatiformes. There is limited biological and fisheries information about the body size at maturity, population size, stock, maximum age and length–mass relationships of Mobula hypos- toma (Bancroft, 1831), better known as the lesser devil ray. -

West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA Bicc)

Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC) SCOPING STUDY ON ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION AND TRADE DELIVERABLE N°6: FINAL SCOPING REPORT ON “ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION, AND TRADE” Email: [email protected] Tel.: +225 44 02 19 17 (Côte d’Ivoire) / +32 495 496 007 (Belgium) Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization Table of content 1. Categorization of the issue ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Chondrichthyans ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1. sharks, rays excluded .......................................................................................................................... 3 a) Status ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2. Rays ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 a) Status ..................................................................................................................................................... -

GENUS Mobula) in CMS APPENDIX I and II

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/ScC18/Doc.7.2.10 MIGRATORY 11 June 2014 SPECIES Original: English 18th MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 1-3 July 2014 Agenda Item 7.2 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ALL SPECIES OF MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) IN CMS APPENDIX I AND II Summary The Government of Fiji has submitted a proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in CMS Appendix I th and II at the 11 Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP11), 4-9 November 2014, Quito, Ecuador. An advanced unedited version of the proposal, as received from the proponent Party, is reproduced under this cover for its early consideration by the Scientific Council. It will be replaced by the final version as soon as possible. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/ScC18/Doc.7.2.10: Proposal I/10 & II/11 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in Appendix I and II B. PROPONENT: Government of Fiji C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1. Taxon 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Rajiformes 1.3 Subfamily: Mobulinae 1.4 Genus and species: All nine species within the Genus Mobula (Rafinesque, 1810): Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788), Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908), Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, 1892), Mobula eregoodootenkee (Bleeker, 1859),Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula hypostoma (Bancroft, 1831), Mobula rochebrunei (Vaillant, 1879), Mobula munkiana (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987) and any other putative Mobula species. -

Mobulid Rays) Are Slow-Growing, Large-Bodied Animals with Some Species Occurring in Small, Highly Fragmented Populations

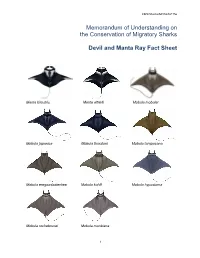

CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Devil and Manta Ray Fact Sheet Manta birostris Manta alfredi Mobula mobular Mobula japanica Mobula thurstoni Mobula tarapacana Mobula eregoodootenkee Mobula kuhlii Mobula hypostoma Mobula rochebrunei Mobula munkiana 1 CMS/Sharks/MOS3/Inf.15e . Class: Chondrichthyes Order: Rajiformes Family: Rajiformes Manta alfredi – Reef Manta Ray Mobula mobular – Giant Devil Ray Mobula japanica – Spinetail Devil Ray Devil and Manta Rays Mobula thurstoni – Bentfin Devil Ray Raie manta & Raies Mobula Mobula tarapacana – Sicklefin Devil Ray Mantas & Rayas Mobula Mobula eregoodootenkee – Longhorned Pygmy Devil Ray Species: Mobula hypostoma – Atlantic Pygmy Devil Illustration: © Marc Dando Ray Mobula rochebrunei – Guinean Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula munkiana – Munk’s Pygmy Devil Ray Mobula kuhlii – Shortfin Devil Ray 1. BIOLOGY Devil and manta rays (family Mobulidae, the mobulid rays) are slow-growing, large-bodied animals with some species occurring in small, highly fragmented populations. Mobulid rays are pelagic, filter-feeders, with populations sparsely distributed across tropical and warm temperate oceans. Currently, nine species of devil ray (genus Mobula) and two species of manta ray (genus Manta) are recognized by CMS1. Mobulid rays have among the lowest fecundity of all elasmobranchs (1 young every 2-3 years), and a late age of maturity (up to 8 years), resulting in population growth rates among the lowest for elasmobranchs (Dulvy et al. 2014; Pardo et al 2016). 2. DISTRIBUTION The three largest-bodied species of Mobula (M. japanica, M. tarapacana, and M. thurstoni), and the oceanic manta (M. birostris) have circumglobal tropical and subtropical geographic ranges. The overlapping range distributions of mobulids, difficulty in differentiating between species, and lack of standardized reporting of fisheries data make it difficult to determine each species’ geographical extent. -

Assessing Sharks and Rays in Shallow Coastal Habitats Using Baited

Assessing sharks and rays in shallow coastal habitats using baited underwater video and aerial surveys in the Red Sea Thesis by Ashlie J. McIvor In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Thuwal, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia May, 2020 2 EXAMINATION COMMITTEE PAGE The thesis of Ashlie Jane McIvor is approved by the examination committee. Committee Chairperson: Prof. Michael Berumen Committee Members: Prof. Burton Jones, Dr. Darren Coker, Dr. Julia Spaet [external] 3 © May, 2020 Ashlie J. McIvor All Rights Reserved 4 ABSTRACT Years of unregulated fishing activity have resulted in low abundances of elasmobranch species in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Coastal populations of sharks and rays in the region remain largely understudied and may be at risk from large-scale coastal development projects. Here we aim to address this pressing need for information by using fish market, unmanned aerial vehicle and baited remote underwater video surveys to quantify the abundance and diversity of sharks and rays in coastal habitats in the Saudi Arabian central Red Sea. Our analysis showed that the majority of observed individuals were batoids, specifically blue-spotted ribbontail stingrays (Taeniura lymma) and reticulate whiprays (Himantura sp.). Aerial surveys observed a catch per unit effort two orders of magnitude greater than underwater video surveys, yet did not detect any shark species. In contrast, baited camera surveys observed both lemon sharks (Negaprion acutidens) and tawny nurse sharks (Nebrius ferrugineus), but in very low quantities (one individual of each species). The combination of survey techniques revealed a higher diversity of elasmobranch presence than using either method alone, however many species of elasmobranch known to exist in the Red Sea were not detected. -

Devils in Distress: the Plight of Mobula Rays

CMS/Sharks/MOS2/Inf.14 Devils in Distress The Plight of Mobula Rays A school of Atlantic pygmy devil rays (Mobula hypostoma) off the Yucatán Peninsula in the Caribbean | Photo © Shawn Henrichs obula rays (Mobula spp.; Family: Mobulidae; commonly referred to as devil rays) are at great risk of severe global Mpopulation declines due to target and incidental fishing pressure1. Similar to the closely related and larger manta rays (Manta spp.)*, Mobula generally grow slowly, mature late, and produce few offspring over long lifetimes1,2. This life history strategy, coupled with their migratory nature and inherent schooling behaviour, makes these species extremely vulnerable to overexploitation. Escalating demand for dried Mobula gill plates for use in Chinese medicine, as well as meat and cartilage, has led to targeting of these vulnerable species through fisheries that are largely unregulated and unmonitored. Significant catch declines have been observed in a number of locations in the Indo-Pacific, Eastern Pacific, and Indian Ocean regions, often despite evidence of increased fishing effort. Population declines are likely occurring in other locations, but have gone unnoticed. Morphological similarities across the nine Mobula spp. and their traded gill plates, combined with overlapping geographic distributions, make species identification difficult. As a result, detailed reporting of catches from the vast majority of countries is lacking, presenting a challenge for population assessment. Measures to ensure sustainability of Mobula catch through fisheries management and international trade controls are also currently lacking. Change is needed now before overfishing leads to severe, perhaps irreparable depletion. Listing Mobula under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) is warranted to improve fisheries and trade data, establish science-based exports limits, bolster enforcement of national protections, and complement listing under the Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). -

MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) in CMS APPENDIX I and II

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/ MIGRATORY Rev.1 4 November 2014 SPECIES Original: English 11th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Quito, Ecuador, 4-9 November 2014 Agenda Item 24.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ALL SPECIES OF MOBULA RAYS (GENUS Mobula) IN CMS APPENDIX I AND II Summary: The Government of Fiji has submitted a proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in CMS Appendix I and II at the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP11), 4-9 November 2014, Quito, Ecuador. A revised proposal for the inclusion of all species of Mobula Rays (Mobula) in CMS Appendices I and II was subsequently submitted by Fiji pursuant to Rule 11 of the COP Rules of Procedure. The proposal is reproduced under this cover for a decision on its approval or rejection by the Conference of the Parties. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the Meeting. Delegates are requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.24.1.10/Rev.1: Proposal I/10 & II/11 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of mobula rays, Genus Mobula, in Appendix I and II B. PROPONENT: Government of Fiji C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1. Taxon 1.1 Class: Chondrichthyes, subclass Elasmobranchii 1.2 Order: Rajiformes 1.3 Subfamily: Mobulinae 1.4 Genus and species: All nine species within the Genus Mobula (Rafinesque, 1810): Mobula mobular (Bonnaterre, 1788), Mobula japanica (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula thurstoni (Lloyd, 1908), Mobula tarapacana (Philippi, 1892), Mobula eregoodootenkee (Bleeker, 1859),Mobula kuhlii (Müller & Henle, 1841), Mobula hypostoma (Bancroft, 1831), Mobula rochebrunei (Vaillant, 1879), Mobula munkiana (Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, 1987) and any other putative Mobula species. -

The Shark and Ray Trade in Singapore

TRAFFIC THE SHARK AND RAY TRADE REPORT IN SINGAPORE MAY 2017 Boon Pei Ya TTRAFFIC-sg-sharkray-trade.pdfRAFFIC-sg-sharkray-trade.pdf ..pdfpdf 1 226/05/20176/05/2017 110:07:210:07:21 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Suite 12A-01, Level 12A, Tower 1, Wisma AmFirst, Jalan Stadium SS 7/15, 47301 Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2017. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-63-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Boon, P.Y. (2017). The Shark and Ray Trade in Singapore. TRAFFIC, Southeast Asia Regional Office, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: Manta Ray. -

Annex 13 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

CoP17 Doc. 88.3 Annex 13 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) FW: FAO EXPERT ADVISORY PANEL FOR ASSESSMENT OF CITES MARINE AND AQUATIC SPECIES PROPOSALS. Rome, Italy. 6-10 June 2016 VanAnrooy, Raymon to: [email protected] 26/05/2016 15:12 (FAOSLC) Cc: "Elena KWITSINSKAIA ([email protected])" […] Fyi, let's see if we get some response from the Caribbean countries. Of course only 2 proposed species are of importance for the countries I expect. Kind regards Raymon -----Original Message----- […] Dear Chief Fisheries officers, Directors and National Focal points of WECAFC members, The FAO has the responsibility to organize a CITES Expert Advisory Panel for the assessment of proposals to amend CITES Appendices I and II for marine and aquatic species. FAO then reports information and advice as appropriate, on each listing proposal. This report is delivered in good time to all Member Countries of FAO, the CITES Secretariat and CITES Parties, prior to the CITES Conference of the Parties (COP) where the proposed amendment/s will be decided. The CITES Conference of the Parties (COP17) is scheduled to take place in South Africa in 24 September- 5 October this year. The final list of species for which proposals have been made for CITES listing amendment, have now been posted (https://cites.org/eng/cop/17/prop/index.php). Please find here below the names of the marine and aquatic commercial species for your interest: v Thresher sharks (Alopias superciliosus, bigeye thresher shark, Alopias vulpinus, common