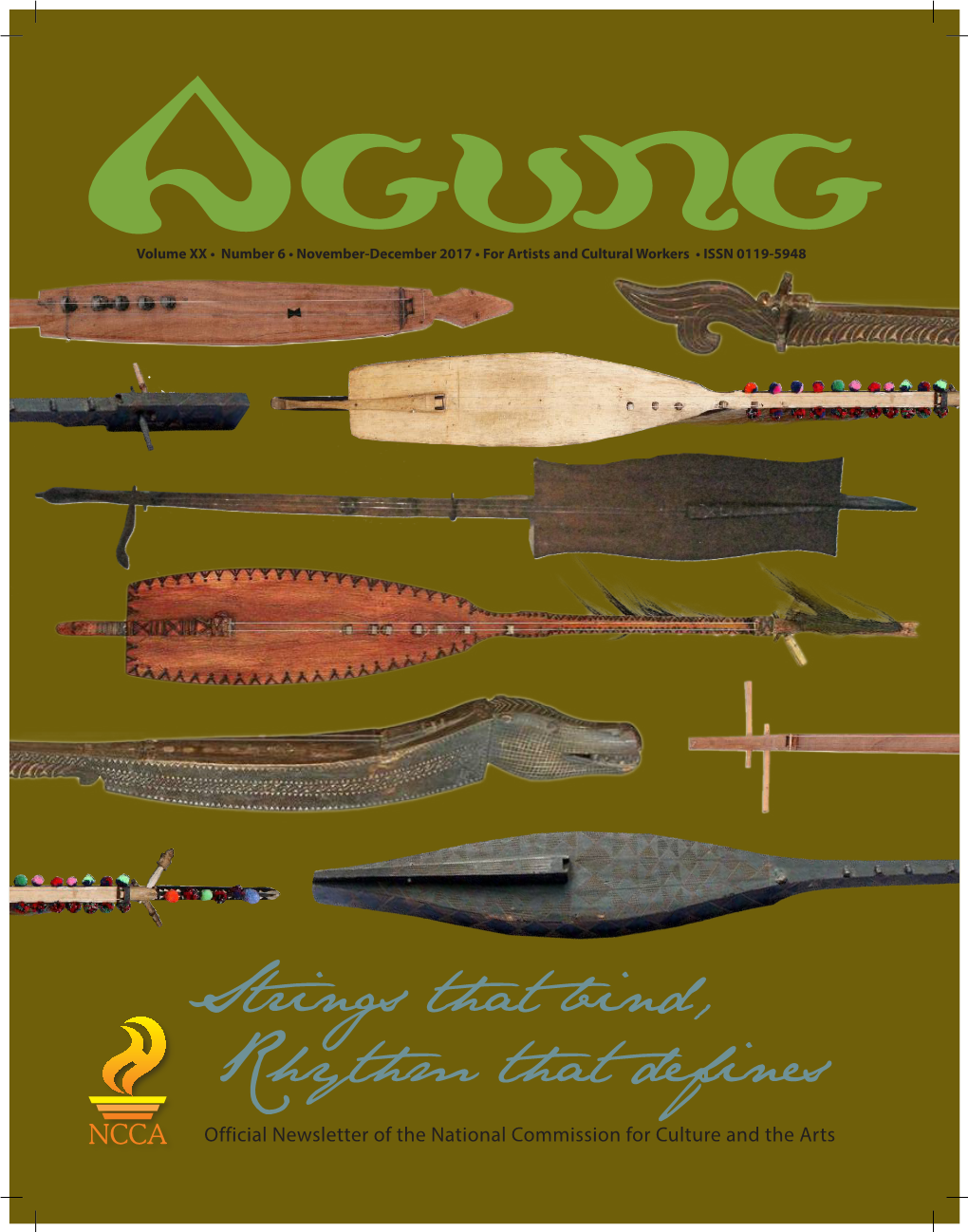

Strings That Bind, Rhythm That Defines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung Trey Atticus Spadone SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Volcanology Commons Recommended Citation Spadone, Trey Atticus, "There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3165. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3165 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. There She Blows: Public Perceptions of Mt. Merapi and Mt. Agung Trey Atticus Spadone Project Advisor: Rose Tirtalistyani SIT Study Abroad Indonesia: Arts, Religion, and Social Change Spring 2019 PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF MT. MERAPI AND MT. AGUNG 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Philippine Music Instruments CORAZON CANAVE-DIOQUINO Music Instruments, Mechanisms That Produce Sounds, Have Been Used for Various Purposes

Philippine Music Instruments CORAZON CANAVE-DIOQUINO Music instruments, mechanisms that produce sounds, have been used for various purposes. In earlier times they were also used as an adjunct to dance or to labor. In later civilizations, instrumental music was used for entertainment. Present day musicological studies, following the Hornbostel-Sachs classification, divide instruments into the following categories: idiophones, aerophones, chordophones, and membranophones. Idiophones Instruments that produce sound from the substance of the instrument itself (wood or metal) are classified as idiophones. They are further subdivided into those that are struck, scraped, plucked, shaken, or rubbed. In the Philippines there are metal and wooden (principally bamboo) idiophones. Metal idiophonse are of two categories: flat gongs and bossed gongs. Flat gongs made of bronze, brass, or iron, are found principally in the north among the Isneg, Tingguian, Kalinga, Bontok, Ibaloi, Kankanai, Gaddang, Ifugao, and Ilonggot. They are most commonly referred to as gangsa . The gongs vary in sized, the average are struck with wooden sticks, padded wooden sticks, or slapped with the palm of the hand. Gong playing among the Cordillera highlanders is an integral part of peace pact gatherings, marriages, prestige ceremonies, feasts, or rituals. In southern Philippines, gongs have a central profusion or knot, hence the term bossed gongs. They are three of types: (1) sets of graduated gongs laid in a row called the kulintang ; (2) larger, deep-rimmed gongs with sides that are turned in called agung , and (3) gongs with narrower rims and less prominent bosses called gandingan . These gongs may be played alone but are often combined with other instruments to form various types of ensembles. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming the Artist, Composing the Philippines: Listening for the Nation in the National Artist Award A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Neal D. Matherne June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Sally Ann Ness Dr. Jonathan Ritter Dr. Christina Schwenkel Copyright by Neal D. Matherne 2014 The Dissertation of Neal D. Matherne is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This work is the result of four years spent in two countries (the U.S. and the Philippines). A small army of people believed in this project and I am eternally grateful. Thank you to my committee members: Rene Lysloff, Sally Ness, Jonathan Ritter, Christina Schwenkel. It is an honor to receive your expert commentary on my research. And to my mentor and chair, Deborah Wong: although we may see this dissertation as the end of a long journey together, I will forever benefit from your words and your example. You taught me that a scholar is not simply an expert, but a responsible citizen of the university, the community, the nation, and the world. I am truly grateful for your time, patience, and efforts during the application, research, and writing phases of this work. This dissertation would not have been possible without a year-long research grant (2011-2012) from the IIE Graduate Fellowship for International Study with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I was one of eighty fortunate scholars who received this fellowship after the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program was cancelled by the U.S. -

Sociología Del Kulintang

CUADERNOS DE MÚSICA IBEROAMERICANA. Vol. 28 enero-diciembre 2015, 7-36 ISSN: 1136-5536 ISAAC DONOSO Universidad de Alicante Sociología del kulintang El kulintang y su orquesta forman la música más singular de las sociedades musulma- nas del sur del archipiélago Filipino. En este trabajo se estudia el significado social de la música de kulintang, sus raíces preislámicas y sus roles en una sociedad islámica, desde las descripciones históricas del siglo XVI hasta la actualidad. La finalidad es establecer la realidad social de la música de kulintang históricamente y su posición actual en una sociedad fili- pina que se enfrenta a un mundo global con fragilidad en su conciencia identitaria. Palabras clave: kulintang, música filipina, islam en Filipinas, moros, sociología de la música, identidad musical. Kulintang and its ensembles represent the most unique music of the Muslim communities in the Southern Philippines. This study examines the social significance of kulintang music, its pre-Islamic roots and its roles in an Islamic society, from the historical descriptions dating back to sixteenth century to the present. The article’s objective is to establish the social reality of kulintang music in history and its present position in a Philippine society facing a global world with a fragile awareness of identity. Keywords: Kulintang, Philippine music, Islam in the Philippines, Moors, music sociology, musical identity. Aproximación a la sociedad islámica de Filipinas La presencia del islam en el archipiélago Filipino tiene su origen en el proceso de islamización que en el Sudeste asiático tuvo lugar como con- secuencia de las rutas comerciales que unían los puertos musulmanes de Oriente próximo con China1. -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

Ludwig Musser Concert Percussion 2013 Catalog

Welcome to the world of Ludwig/Musser Concert Percussion. The instruments in this catalog represent the finest quality and sound in percussion instruments today from a company that has been making instruments and accessories in the USA for decades. Ludwig is “The Most famous Name in Drums” since 1909 and Musser is “First in Class” for mallet percussion since 1948. Ludwig & Musser aren’t just brand names, they are men’s names. William F. Ludwig Sr. & William F. Ludwig II were gifted percussionists and astute businessmen who were innovators in the world of percussion. Clair Omar Musser was also a visionary mallet percussionist, composer, designer, engineer and leader who founded the Musser Company to be the American leader in mallet instruments. Both companies originated in the Chicago area. They joined forces in the 1960’s and originated the concept of “Total Percussion." With our experience as a manufacturer, we have a dedicated staff of craftsmen and marketing professionals that are sensitive to the needs of the percussionist. Several on our staff are active percussionists today and have that same passion for excellence in design, quality and performance as did our founders. We are proud to be an American company competing in a global economy. This Ludwig Musser Concert Percussion Catalog is dedicated to the late William F. Ludwig II Musser Marimbas, Xylophones, Chimes, Bells, & Vibraphones are available in “The Chief.” His vision for a “Total Percussion” a wide range of sizes and models to completely satisfy the needs of beginners, company was something he created at Ludwig schools, universities and professionals. -

The Application of Bonang Gamelan Music Based on Mobile Application

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-6, March 2020 The Application of Bonang Gamelan Music Based on Mobile Application Wan Hassan W A S., Rosli D.I., Ariffin A., Ahmad F., Jamin J learning which was practiced at local institutions of higher Abstract: The application of bonang gamelan music based on learning such as Malaysian Open University (OUM) (Zoraini, mobile application was developed with the aim of maintaining the 2010). This aspect will indirectly increase the productivity of tradition of traditional musical instruments in the society of this individual skills in daily life as well as foster continuous modern day. Users can recognise and learn how to play the traditional musical instruments, especially bonang gamelan by learning practices. Striking from the use of distance learning using mobile phone technology. This application provides and e-learning methods, the education world strives to convenience for users without spending time and money and they explore the dimensions of learning for users who want to learn can also access it anywhere. The development of this animated anytime and anywhere. Then, the term learning method is application is based on the ADDIE methodology and uses Adobe mobile or is called m-learning (Brown, 2005). This Flash software as a platform to develop this music app. The respondents involved in the development of this music app consist m-learning method is akin to self-learning using mobile of six (6) specialists in bonang gamelan music and IT devices such as mobile telephony, personal digital assistant professionals. The user respondents were ten (10) students of the (PDA), Palm Talk and others as learning tools (Wagner, Faculty of Technical and Vocational Education (FPTV). -

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Korean March Defying Jnnta

"'v-'r—s V- '.- y'’- f >•'*,« V'‘V ; \- •. .. •■‘J' ■/ t C b s d a v , m a b c h m , 1 9 m A n n t. D dr Nri P i m m K m lilldftB'tW lLVB': The Weathet lEvpttfng F orth# Week Elided Foreeiaet ef H. 8. Wsothar nari— M a n iiU ,lM I Partial ’ cleaHiig and Mreeay to> chairman is Chester Andrew of Mid. give# them a sebss of Mystic Review Women’s Bene Hie Brtitlah American Club iVUl Ity and self estsem they need *t night with little drop la tempera fit Assn., will meet tonii^t at 8 have its aimiial meeting with elec 116 Ootemon Rd. Speaker Explains 1 3 ,9 6 6 About Town VSCG Band that age, ture. Lowest atronnd SO. Iw tty at Odd Fellows Hall. Guan& are tion of officers Saturday at 6 p.m. William L. Broodwell Is the softheAadlt cloudy, breesy and eoathraed eeoi at the cKibhouse. bandmaster. He has been with the Youth Prohlems ■ H ie Rev. James L. Ransom, New I Canter Churefa Mottien Ghib reminded to attend for guard I o f OirmUatioB lliursday^' HUgheet iUi to 40. work. band olnce 1946 and Its conductor pastor of the PrSebyterian Ohur^, M ancHe»ter-^A City of Village Charm ' i|40 xnaat tom om m nt 8 pjn. In The Rent. Clifford O. Simpson, To ploy f or since 1960. ’Hie band’s strength is Home environment,,1s extremely and Roger Cottle were hosts at the LOW Prie^st tita Mnderg^arten r o o m of the Disabled .^merican Veterans pastor of Center Congregational 47 men. -

Evolution of the Japanese Marimba ~A History of Design Through Japan's 5 Major Manufacurers~

Fujii Database vol.2 Evolution of the Japanese Marimba ~A History of Design Through Japan's 5 Major Manufacurers~ By Mutsuko Fujii and Senzoku Marimba Research Group November 2009 Fujii Database vol.2 Evolution of the Japanese Marimba ~ A History of Design Through Japan’s Five Major Manufacturers By Mutsuko Fujii and Senzoku Marimba Research Group In 2006, the first “Fujii Database of Japanese Marimba Works,” a survey of Japanese marimba pieces, was released by Mutsuko Fujii and the Senzoku Marimba Research Group and donated to the PAS archive. Since then, we hoped to make another report on the history of Japanese keyboard percussion - including concert xylophones and marimbas. Between 2002 and 2005, the Senzoku Marimba Research Group and I visited the presidents or heads of the five named companies directly and heard about the history of development to date. We have compiled the information in this database. We are delighted to announce the second report as “Fuji Database of the Evolution of the Japanese Marimba ~ A History of Design Through Japan’s Five Major Manufacturers.” The database is a list of Japanese concert xylophones and marimbas sorted by year of manufacture as reported by Japan’s top five keyboard percussion makers. (Only models undergoing major changes are listed due to space limitations.) Quite a few years ago, each firm had manufactured a portable xylophone – a simple, handy instrument with only a keyboard for playing on a table top - before starting to create concert xylophones and marimbas. This was directly related to the Japanese school education concept. In 1947, the Japanese Ministry of Education directed all domestic elementary schools to use the xylophone as a pedagogical instrument based on guidelines taken from the Fundamental Education Act. -

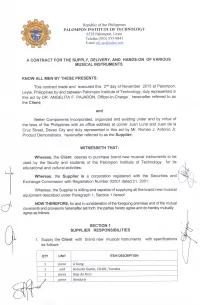

Pit [email protected]

Republic of the Philippines PALOMPON INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 6538 Palompon, Leyte Telefax (053) 555-9841 E-mail: pit [email protected] A CONTRACT FOR THE SUPPLY, DELIVERY, AND HANDS-ON OF VARIOUS MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS: This contract made and executed this 2nd day of November 2015 at Palompon, Leyte, Philippines by and between Palompon Institute of Technology, duly represented in this act by DR. ANGELITA F. PAJARON, Officer-ln-Charge , hereinafter referred to as the Client; and Better Components Incorporated, organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the Philippines with an office address at corner Juan Luna and Juan de la Cruz Street, Davao City and duly represented in this act by Mr. Romeo J. Antonio Jr, Product Demonstrator, hereinafter referred to as the Supplier; WITNESSETH THAT: Whereas, the Client desires to purchase brand new musical instruments to be used by the faculty and students of the Palompon Institute of Technology for its educational and cultural activities; Whereas, the Supplier is a corporation registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission with Registration Number 02001 dated 21, 2001; Whereas, the Supplier is willing and capable of supplying all the brand new musical equipment described under Paragraph 1, Section 1 hereof. NOW THEREFORE, for and in consideration of the foregoing premises and of the mutual covenants and provisions hereinafter set forth, the parties hereto agree and do hereby mutually agree as follows: SECTION 1 SUPPLIER RESPONSIBILITIES 1. Supply the