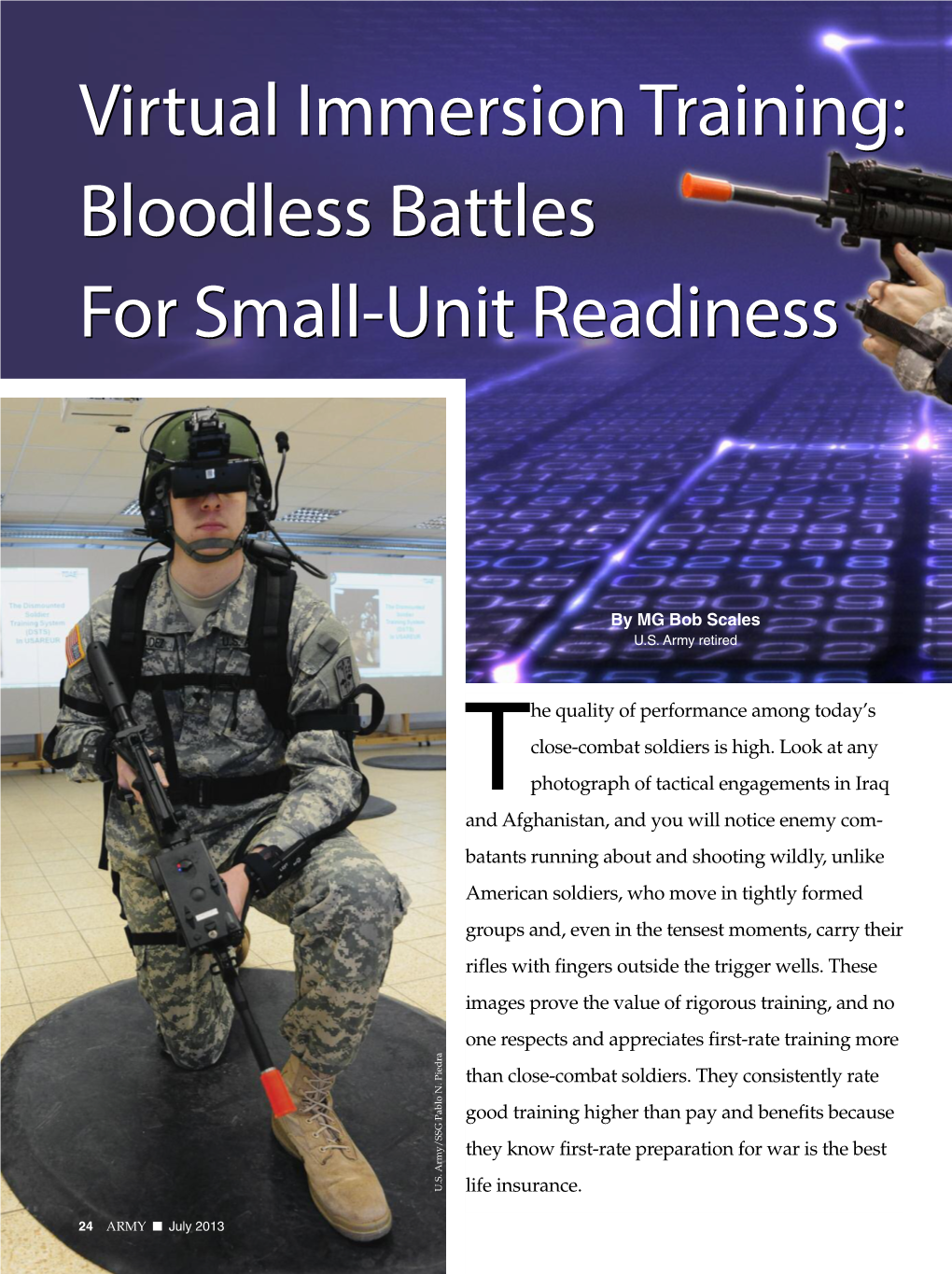

Virtual Immersion Training: Bloodless Battles for Small-Unit Readiness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prairie Sentinelvolume 8

Illinois National Guard Prairie SentinelVolume 8 On the Road Again: 233rd Military Police Company Conducts Road to War Training Homeward Bound: 2nd Battalion, 13oth Infantry Regiment Returns home Best of the BEST: Bilateral Embedded Staff Team A-25 caps off BEST co-deployment missions Nov-Dec 2020 Illinois National Guard 6 8 9 10 12 15 16 18 21 22 24 For more, click a photo or the title of the story. Highlighting Diversity: ILNG Diversity Council host Native American speaker 4 The Illinois National Guard Diversity Council hosts CMSgt, Teresa Ray. By Sgt. LeAnne Withrow, 139th MPAD ILARNG Top Recruiter and first sergeant from same company 5 Company D, Illinois Army National Guard Recruiting and Retention Battalion based in Aurora, Illinois, is the home of the top recruiter and recruiting first sergeant. By Sgt. 1st Class Kassidy Snyder, Illinois Army National Guard Recruiting and Retention Battalion Homeward Bound: 2/130’s Companies B and C return home 6 Soldiers from 2nd Battalion, 130th Infantry Regiment’s B and C companies return home after deploying to Bahrain and Jordan Oct. 31. By Barb Wilson, Illinois National Guard Public Affairs Joint Force Medical Detachment commander promoted to colonel 8 Jayson Coble, of Lincoln, Illinois, was promoted to the rank of colonel Nov. 7 at the Illinois State Military Museum. By Barb Wilson, Illinois National Guard Public Affairs High Capacity: 126th Maintenance Group Earns fourth consecutive mission capability title 9 A photo spread highlighting the 126th MXG’s quintuple success. By Tech. Sgt. Cesaron White and Senior Airman Elise Stout, 126th Air Refueling Wing Public Affairs Back to back, Shoulder to Shoulder: 108th earns back to back sustainment awards 10 Two exceptional Illinois Army National Guard teams won the prestigious U.S. -

Summer 2011 Fired up About

MAGAZINE OF THE OHIO ARMY AND AIR NATIONAL GUARD SUMMER 2011 Fired up about SAFETYPAGES 8-9 Ohio National Guard members learn valuable principles to implement back at their units during State Safety School FINAL ISSUE: This will be the last printed issue of the Buckeye Guard. Learn about some of our new media initiatives in place, and how you now can get your Ohio National Guard news, on page 4. GUARD SNAPSHOTS BUCKEYE GUARD roll call Volume 34, No. 2 Summer 2011 The Buckeye Guard is an authorized publication for members Sgt. Corey Giere of the Department of Defense. Contents of the Buckeye Guard (right) of Headquarters are not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, the Departments of the Army and Air Force, or and Headquarters the Adjutant General of Ohio. The Buckeye Guard is published Company, Special quarterly under the supervision of the Public Affairs Office, Ohio Adjutant General’s Department, 2825 W. Dublin Granville Troops Battalion, Road, Columbus, Ohio 43235-2789. The editorial content of this 37th Infantry Brigade publication is the responsibility of the Adjutant General of Ohio’s Director of Communications. Direct communication is authorized Combat Team, to the editor, phone: (614) 336-7003; fax: (614) 336-7410; or provides suppressive send e-mail to [email protected]. The Buckeye Guard is distributed free to members of the Ohio Army and Air fire with blank rounds National Guard and to other interested persons at their request. as the rest of his fire Guard members and their Families are encouraged to submit any articles meant to inform, educate or entertain Buckeye Guard team runs for cover readers, including stories about interesting Guard personalities and unique unit training. -

The Employment Situation of Veterans

February 2013 The Employment Situation of Veterans Today, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the overall unemployment rate for all Americans (population 16 and over) edged down to 7.7%. The employment situation for veterans overall has also experienced a decrease in unemployment. The unemployment rates for all veterans decreased from 8.3% in January to 7.8% in February. For Gulf War era II veterans (post-9/11 generation), the unemployment rate has also decreased from 11.7% to 9.4%. However, the youngest post-9/11 veterans, those ages 20-24, saw a 6.6% increase in their unemployment rate from January to February, which remains the highest unemployment rate of all age groups at 38.0%. This rate of the young post-9/11 veterans is more than twice as high as their nonveteran counterparts. About 60% of the young post-9/11 veterans, ages 20-24, have been unemployed for more than five weeks. Of the 203,000 unemployed post-9/11 veterans ages 20 and over, 13% have been unemployed for less than five weeks, 30% unemployed for five to 14 weeks and 57% have been unemployed for 15 weeks or more. For female post-9/11 veterans, the unemployment rate decreased from 17.1% to 11.6%, but remains higher than their non-veteran counterpart (7.0%). Male post-9/11 veterans saw a decrease from 10.5% to 9.0% but remains slightly higher than their non-veteran counterparts (8.0%). The unemployment rate for post-9/11 White veterans, 8.9%, remains higher than that of their non-veteran counterparts, at 6.7%. -

Barracks Behind Bars II in VETERAN-SPECIFIC HOUSING UNITS, VETERANS HELP VETERANS HELP THEMSELVES U.S

U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections PRISONS Barracks Behind Bars II IN VETERAN-SPECIFIC HOUSING UNITS, VETERANS HELP VETERANS HELP THEMSELVES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF CORRECTIONS 320 FIRST STREET, NW WASHINGTON, DC 20534 SHAINA VANEK ACTING DIRECTOR ROBERT M. BROWN, JR. SENIOR DEPUTY DIRECTOR HOLLY BUSBY CHIEF, COMMUNITY SERVICES DIVISION RONALD TAYLOR CHIEF, PRISONS DIVISION GREGORY CRAWFORD PROJECT MANAGER NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF CORRECTIONS WWW.NICIC.GOV PRISONS Barracks Behind Bars II IN VETERAN-SPECIFIC HOUSING UNITS, VETERANS HELP VETERANS HELP THEMSELVES Written by Deanne Benos, Open Road Policy, Bernard Edelman, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Greg Crawford, National Institute of Corrections. Edited by Donna Ledbetter, National Institute of Corrections. Special thanks to Nicholas Stefanovic for his contributions to this project. The National Institute of Corrections, in partnership with the Justice-Involved Veterans Network, has developed this white paper that highlights specialized housing units in prisons. October 2019 | Project Number 16P1031 and 16J1080 ACCESSION NUMBER: 033092 DISCLAIMER This document was funded by the National Institute of Corrections, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. The National Institute of Corrections reserves the right to reproduce, publish, translate, or otherwise use and to authorize others to publish and use all or any part of the copyrighted material contained in this publication. FEEDBACK SURVEY STATEMENT The National Institute of Corrections values your feedback. Please follow the link below to complete a user feedback survey about this publication. -

The 610Th Tank Destroyer Battalion

5/14/2019 THE 61OTH TANK DESTROYER BATTALION THE 610TH TANK DESTROYER BATTALION by Captain Roy T. McGrann 1946 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BOOK I PRE-COMBAT CHAPTER I: ACTIVATION CHAPTER II: CAMP BOWIE, TEXAS CHAPTER III: CAMP HOOD, TEXAS CHAPTER IV: CAMP ATTERBURY, INDIANA file:///E:/Documents/Military/Militaryfile:///E:/Documents/Military/Military Documents/Unit Documents/Unit Documents/610th Documents/610th TD TD Bn/Files Bn/Files from from McGrann McGrann family/index.html family/index.html 1/2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BOOK I PRE-COMBAT CHAPTER I: ACTIVATION CHAPTER II: CAMP BOWIE , TEXAS CHAPTER III: CAMP HOOD, TEXAS CHAPTER IV: CAMP ATTERBURY, IN DIANA CHAPTER V: TENNESSEE MANEUVERS CHAPTER VI: REORGANIZATION CHAPTER VII: CENSORED BOOK II COMBAT EXPERIENCE AS A TOWED BATTALION CHAPTER VIII: ARGENTAN CHAPTER IX: THE MOSELLE RIVER BOOK III COMBAT EXPERIENCE AS SELF-PROPELLED BATTALION CHAPTER X: THE SAAR RIVER OFFENSIVE CHAPTER XI: THE ARDENNES OR “BULGE” CHAPTER XII: BELGIUM AND THE SCHNEE E IFEL CHAPTER XIII: ALSACE AND THE RHINE CHAPTER XIV: CENTRAL GERMANY BOOK IV OCCUPATION DUTY CHAPTER XV: KREIS EICHSTATT CHAPTER XVI: NURNBERG CHAPTER XVII: GOING HOME BOOK V REPORTS ON COMPANY ACTION CHAPTER XVIII: COMPANY STORIES CHAPTER XIX: AWARDS AND DECOR ATIONS CHAPTER XX: NAMES AND ADDRESSES (as of 1946) file:///E:/Documents/Military/Military Documents/Unit Documents/610th TD Bn/Files from McGrann family/index.html 1/2 5/14/2019 Introduction The 610th Tank Destroyer Battalion INTRODUCTION This book is the fulfillment of a promise that I made to Lt. Col. Herold shortly after he joined the Battalion at Camp Hood that at some future date the complete story of the outfit would be gathered into one volume and distributed to the members. -

Economic Impact Analysis of Atterbury-Muscatatuck

Economic Impact Analysis of Atterbury-Muscatatuck V600 CAPSTONE REPORT INDIANA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS APRIL 24, 2013 1 Executive Summary Atterbury-Muscatatuck serves a fundamental purpose in the State of Indiana. Established in 1942 in parts of Bartholomew, Brown, and Johnson counties, Camp Atterbury has proven itself as one of the premier military training and mobilization sites in the nation. The Muscatatuck Urban Training Center in Jennings County supplements an advanced operating environment with unique military facilities and infrastructure. Together, Atterbury-Muscatatuck has a vision to provide to the nation the most realistic, fiscally responsible, contemporary operating environment possible in which to mobilize and train the whole of government team to accomplish missions directed towards protecting the homeland and winning the peace; and support the developmental testing and evaluation of technologies that support those missions. Anecdotal evidence suggested that the presence of Atterbury-Muscatatuck in the local area provides many high quality jobs and supports many local businesses with substantial spending related to post operations. This study has confirmed and quantified the direct impact of these operations, and for the first time, provides an understanding of how spending at Atterbury-Muscatatuck ripples through the economy. These ripple effects, explained in more detail below, create wealth and jobs in the region and State. We found that the post is directly responsible for 2,902 jobs in the region. The post is indirectly, through relationships with suppliers and supporting industries, responsible for 143 additional jobs throughout the remainder of the State. Lastly, through induced effects, or spending of households from direct employment, the post supports an additional 1,131 jobs in the State of Indiana, for a total employment impact of 4,176 jobs. -

Biological Assessment Effects to Indiana Bats Ongoing

BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT EFFECTS TO INDIANA BATS FROM ONGOING AND ANTICIPATED FUTURE MILITARY ACTIVITIES CAMP ATTERBURY EDINBURGH, INDIANA PREPARED FOR Camp Atterbury Edinburgh, Indiana PREPARED BY Tetra Tech, Inc. 10306 Eaton Place, Suite 340 Fairfax, Virginia 22030 Contract No. DACW01-99-D-0029, Delivery Order No. 0030 Draft Biological Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................... ES-1 SECTION 1.0: INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 1-1 1.1 REPORT ORGANIZATION ........................................... 1-3 1.2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ............................................. 1-4 SECTION 2.0: ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE ........................................... 2-1 SECTION 3.0: DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED ACTION .............................. 3-1 3.1 MILITARY MISSION ............................................... 3-1 3.2 CURRENT MILITARY ACTIVITIES ................................... 3-3 3.3 ANTICIPATED FUTURE MILITARY ACTIVITIES ....................... 3-13 SECTION 4.0: SPECIES OF CONCERN ................................................. 4-1 4.1 INDIANA BAT (MYOTIS SODALIS) .................................... 4-1 4.1.1 Physical Description .......................................... 4-1 4.1.2 Distribution ................................................. 4-1 4.1.3 Habitat Requirements .......................................... 4-3 4.1.4 Life History ................................................. 4-7 4.1.5 Reasons for Decline .......................................... -

Rankings for Military Installations Based on Grassland Potential

Table 5-4. Selected military installations in the eastern US with the potential to provide significant grassland habitat for grassland bird conservation Species richness* Ranking Based on Identification Total area Installation Grassland Potential number Type State (Ha) Wintering Breeding Fort Campbell 1 9 Army Kentucky 42772 11 7 Avon Park Bombing and Gunnery Range 2 37 Air Force Florida 34084 11 4 Letterkenny Army Depot 3 13 Army Pennsylvania 7823 9 9 Naval Weapons Support Center, Crane 4 6 Navy Indiana 25165 9 9 Redstone Arsenal 5 11 Army Alabama 15740 9 5 Fort McCoy 6 1 Army Wisconsin 25558 5 11 Fort Jackson 7 29 Army South Carolina 21331 10 5 Fort Bragg 8 27 Army North Carolina 53365 11 4 Fort Detrick 9 16 Army Maryland 852 9 8 Fort Rucker 10 40 Army Alabama 23920 12 3 Marine Corps Combat Development Command, Quantico 11 17 Marines Virginia 25070 8 6 Fort Drum 12 4 Army New York 44009 8 10 Naval Submarine Base, Kings Bay 13 35 Navy Georgia 5614 12 2 Fort Gordon 14 31 Army Georgia 22384 10 4 Fort A. P. Hill 15 19 Army Virginia 30304 11 4 Blue Grass Army Depot 16 8 Army Kentucky 6014 9 4 Fort Stewart 17 34 Army Georgia 113135 11 3 Camp Blanding 18 36 National Guard Florida 29932 12 2 Camp Atterbury 19 5 National Guard Indiana 16191 9 10 Fort Benning 20 39 Army Georgia 74199 12 4 Fort Polk 21 43 Army Louisiana 46036 13 3 Eglin Air Force Base 22 41 Air Force Florida 184793 12 3 Polaris Missile Facility 23 30 Navy South Carolina 7308 14 2 Fort Pickett 24 26 Army Virginia 15374 11 4 Naval Air Development Center, Warminster 25 14 Navy Pennsylvania -

Texas Lone Star Chapter Home

TEXAS LONE STAR CHAPTER 5427 Weston Drive Fulshear, Texas 77441-4127 February 6, 2021 MEETING: The Texas Lone Star Chapter to be held on Saturday, February 20, 2021 at the South Houston Legion Post 490 located at 11702 Old Galveston Road across from Ellington Field. The meeting will start at 12:30 PM. We will also hold a Convention Planning Meeting at our Chapter Meeting. CHAPTER WEBSITE: Visit the Chapter website: https://texaslonestar82.org /index.html 82ND AIRBORNE DIVISION ASSOCIATION WEBSITE: www.82ndairborneassociation.org/ ASSOCIATION FACEBOOK PAGE: https://www.facebook.com/Texas-Lone-Star-Chapter- 82nd-Airborne-Division-Association 2021 NATIONAL CONVENTION: On January 21, the Chapter held its first Convention Planning Meeting. We discussed the effect of the pandemic on the Convention. Our main concern was the city, county, state and federal government regulation of the pandemic. The hotel contract was revised last April. The date was moved from the first week of August to the second week of August. (August 11-14, 2021). We did reserved the hotel date from August 8- 15, 2021 so if anyone wished to arrive early would receive the hotel convention room price. We have a $7,000 deposit with the hotel and we will lose it if we don’t host the convention unless the government shuts down the city again. The hotel is willing to work with us and not hold us to the attendance count on the contract. What does that mean? It means we need to host the convention and there is no penalty for having less attendance that what is stated in the revised contract. -

A History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 1-2010 A History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Chris J. Cochran Engineer Research and Development Center Champaign IL Construction Engineering Research Lab Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2010. © 2010, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Construction Engineering Research Laboratories. This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 The History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith and Chris J. Cochran January 2010 Construction Engineering Laboratory Research Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 January 2010 The History of American Settlement at Camp Atterbury Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology 1321 Pendleton Street Columbia, SC 29208 Chris J. Cochran Construction Engineering Research Laboratory U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center 2902 Newmark Drive Champaign, IL 61822 Final Report Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Prepared for Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center Environmental Office PO Box 5000 Edinburgh, IN 46124 ERDC/CERL TR-10-3 ii Abstract: This report details the history of 19th and 20th century farm and community settlement within the Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center, IN. -

Migration in Austria Günter Bischof, Dirk Rupnow (Eds.)

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES VOLUME 26 Migration in Austria Günter Bischof, Dirk Rupnow (Eds.) UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Migration in Austria Günter Bischof, Dirk Rupnow (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 26 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2017 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011452 ISBN: 9783903122802 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through a generous grant by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. The College of Liberal Arts at the University of New Orleans, as well as the Vice -

Korean War Atrocities, Hearing, Part 3

KOREAN WAR ATROCITIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON KOREAN WAR ATROCITIES OF TW PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON ., L INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE 01, GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS FIRST SESSION PURSUANT TO S. Res. 40 PART 3 DECEMBER 4, 1953 Printed for the Committee on Government Operations UNITED STATES CIOVRRNMENT PRTNTTNG OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1954 COIIMITTEE ON GOT;EItNi\llENT OPERATIONS JOSEPH R. YCCARTHP, Wisconsin, Chazrwnn KARL E. MUNDT, South Dakota JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas MARGARET CHASE SMITH, Maine HUBERT H. HUMPHREY, Minnesota HENRY C. DWORSHAK, Idaho HENRY M. JACKSON, Washington EVERETT McIiINLEP DIRICSEN, Illinois JOHN F. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JOHN MARSHALL BUTLER, Maryland BTUART SYMINGTON, Missouri CHARLES E. POTTER, Michigan ALTON LENNON, North Caroliua FRANCIS n. FLANAGAN, chief COU~S~~ WALTERL. REYNOLDS,Chief LZcrIC JOSEPH R. McC~RTHY,Wisconsin, Chaimnan KARL #I. MUNDT, South Dakota EVERETT McKINLE'i DIRKSEN, Illinois CHARLES E. POTTER, ~ichigan ROYM. COHN,Chief Coumel FRANCIS P. CARR,Executive Director SCBCOMMITTEEON KOREANWAR ATROCIT~ES CHARLES E. POTTER, Michigan, Chairman I1 CONTENTS Testimony of- Abbott, Lt. Col. Robert, Infantry, 1242d ASU, Rochester, N. Y----- 182 Buttrey, Capt. Linton J., Headquarters, MRTC, Camp Pickett, Va-- 166 Finn, Maj. Frank M., War Crimes Division, Officeof the Judge Advo- cate General, the Pentagon, Washington, D. C ------------------ 217 Gorn, Lt. Col. John W., Office of the Chief of Legislative- Liaison. Department of the Army .................................... 162 Hanley, Col. James M., United States Army, Camp Atterbury, Ind-- 149 Herrmann, Frederick C. 35 East Chandler Street, Evansville, Ind---- 156 Jaramillo, Arturo J., Pueblo, Colo ............................... 167 Locke. Maj. William D., United States Air Force, Headquarters Tacti- cal Air Command, Langley Air Force Base, Va ------_----------- 218 Makarounis, Capt.