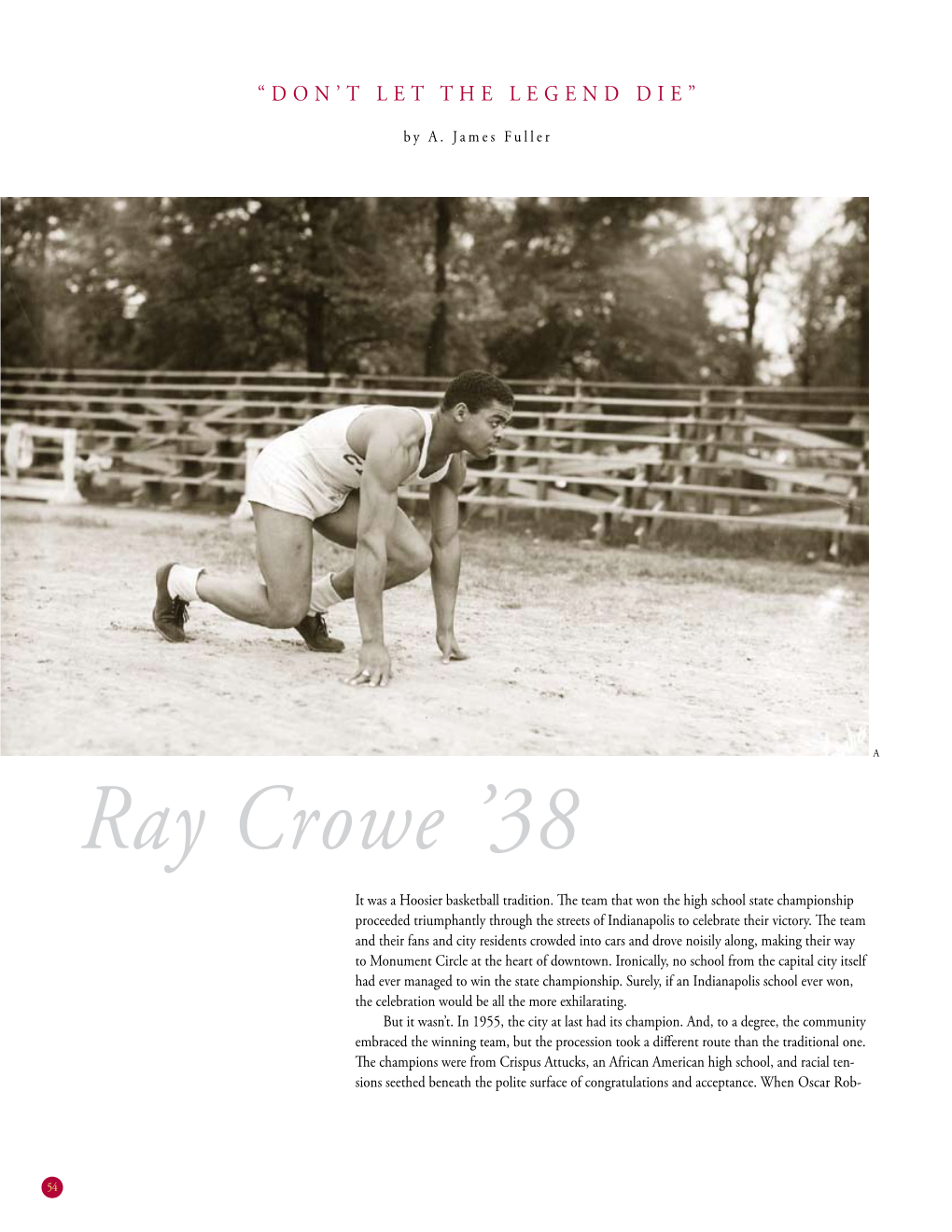

Ray Crowe ’38 It Was a Hoosier Basketball Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 161 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2015 No. 147 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was One from the Fiscal Times, Sep- The little girls beside me, Mr. Speak- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- tember 23, ‘‘U.S. Wasted Billions of er, Eden and Stephanie Balduf, their pore (Mr. STEWART). Dollars Rebuilding Afghanistan.’’ daddy was training Afghanistan citi- The second headline from the New f zens to be policemen, and they were York Times, October 1, ‘‘Afghan Forces shot and killed by the man they were DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO on the Run.’’ training. Poor little girls represent so TEMPORE The third headline, ‘‘U.S. Soldiers many families whose loved ones have The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- Told to Ignore Sexual Abuse of Boys by died in Afghanistan for nothing but a fore the House the following commu- Afghan Military Leaders.’’ waste. I am so outraged about the third nication from the Speaker: With that, Mr. Speaker, I ask God to headline story that I am demanding please bless our men and women in uni- WASHINGTON, DC. answers on the Pentagon’s policy of October 7, 2015. form, please bless America, and, God, permitting Afghan men to rape young I hereby appoint the Honorable CHRIS please wake up the Congress before it boys on U.S. military bases. I have STEWART to act as Speaker pro tempore on is too late on Afghanistan. -

Crispus Attucks High School Scrapbook, 1950-1996

Collection # BV 3469, SC 2697 CRISPUS ATTUCKS HIGH SCHOOL SCRAPBOOK, 1950–1996 Collection Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Wilma L. Gibbs 21 April 2003 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 bound volume, 3 folders COLLECTION: COLLECTION 1950–1996 DATES: PROVENANCE: Billy Sears and Ernest R. Barnett, Indianapolis, July 2002 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2002.0616 NUMBER: NOTES: HISTORICAL SKETCH In 1955, led by Oscar Robertson, Crispus Attucks High School became the first Indianapolis school to win the state basketball championship. The school repeated the honor the following year. Coached by Ray Crowe, the school’s basketball team had won 45 consecutive games when they were named the 1956 Indiana High School Athletic Association (IHSAA) champions. That year during the annual Kentucky vs. Indiana High School All-Stars game, star guard Robertson scored an unprecedented 34 points. Named Indiana’s “Mr. Basketball,” for the tournament, he was also voted the “star of stars” by the sports writers and broadcasters, and elected captain of the squad by his teammates. He was the first player in Indiana history to receive all three honors. Robertson had an outstanding college career while at the University of Cincinnati. He led the nation in scoring from 1958 to 1960, and he was named the outstanding collegiate player in each of those three seasons. -

AUTHOR Renaissance in the Heartland: the Indiana Experience

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 918 SO 030 734 AUTHOR Oliver, John E., Ed. TITLE Renaissance in the Heartland: The Indiana Experience--Images and Encounters. Pathways in Geography Series Title No. 20. INSTITUTION National Council for Geographic Education. ISBN ISBN-1-884136-14-1 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 143p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council for Geographic Education, 16A Leonard Hall, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA 15705. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Geography; *Geography Instruction; Higher Education; Learning Activities; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *Topography IDENTIFIERS Historical Background; *Indiana; National Geography Standards; *State Characteristics ABSTRACT This collection of essays offers many ideas, observations, and descriptions of the state of Indiana to stimulate the study of Indiana's geography. The 25 essays in the collection are as follows: (1) "The Changing Geographic Personality of Indiana" (William A. Dando); (2) "The Ice Age Legacy" (Susan M. Berta); (3) "The Indians" (Ronald A. Janke); (4) "The Pioneer Era" (John R. McGregor); (5) "Indiana since the End of the Civil War" (Darrel Bigham); (6) "The African-American Experience" (Curtis Stevens); (7) "Tracing the Settlement of Indiana through Antique Maps" (Brooks Pearson); (8) "Indianapolis: A Study in Centrality" (Robert Larson);(9) "Industry Serving a Region, a Nation, and a World" (Daniel Knudsen) ; (10) "Hoosier Hysteria: In the Beginning" (Roger Jenkinson);(11) "The National Road" (Thomas Schlereth);(12) "Notable Weather Events" (Gregory Bierly); (13) "Festivals" (Robert Beck) ; (14) "Simple and Plain: A Glimpse of the Amish" (Claudia Crump); (15)"The Dunes" (Stanley Shimer); (16)"Towns and Cities of the Ohio: Reflections" (Claudia Crump); (17) "The Gary Steel Industry" (Mark Reshkin); (18) "The 'Indy 500'" (Gerald Showalter);(19)"The National Geography Standards"; (20) "Graves, Griffins, and Graffiti" (Anne H. -

Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Ca. 1900-1987

Collection # P 0303 Indianapolis Recorder Collection ca. 1900–1987 Collection Information Historical Sketch Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series 1 Description Series 2 Description Series 1 Box and Folder List Series 1 Indices Series 2 Index Series 2 Box and Folder List Cataloging Information Processed by Pamela Tranfield July 1997; January 2000 Updated 10 May 2004 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 179 linear feet ofblack-and-white photographs; 2 linear feet of color photographs; 1.5 linear feet of printed material; 0.5 linear feet of graphics; 0.5 linear feet of manuscripts. COLLECTION DATES: circa 1900–1981 PROVENANCE: George P. Stewart Publishing Company, May 1984, March 1999. RESTRICTIONS: Manuscript material related to Homes for Black Children of Indianapolis is not available for use until 2040. COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material from this collection must be obtained in writing from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: George P. Stewart Collection (M 0556) ACCESSION NUMBERS: 1984.0517; 1999.0353 NOTES: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The Indianapolis Recorder Collection was processed between July 1995 and July 1997, and between August 1999 and January 2000. The Indiana Historical Society thanks the following volunteers for their assistance in identifying people, organizations, and events in these photographs: Stanley Warren, Ray Crowe, Theodore Boyd, Barbara Shankland, Jim Cummings, and Wilma Gibbs. HISTORICAL SKETCH George Pheldon Stewart and William H. Porter established the Indianapolis Recorder, an African American newspaper, in 1895 at 122 West New York Street in Indianapolis. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7195

October 7, 2015 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S7195 could matter most—in Afghanistan, in Budget Act of 1974 and the waiver pro- The clerk will call the roll. the Pacific, in Ukraine, in Iraq, and in visions of applicable budget resolu- The senior assistant legislative clerk Syria. Vetoing the NDAA would be yet tions, I move to waive all applicable called the roll. another of these failures, and it would sections of that act and applicable Mr. CORNYN. The following Senators be reminiscent of a bygone day, when budget resolutions for purposes of the are necessarily absent: the Senator the fecklessness of those days were so conference report to accompany H.R. from South Carolina (Mr. GRAHAM), the accurately described by Winston 1735, and I ask for the yeas and nays. Senator from Kansas (Mr. ROBERTS), Churchill. On the floor of the House of The PRESIDING OFFICER. Is there a and the Senator from Florida (Mr. Commons, he said: sufficient second? RUBIO). When the situation was manageable it was There appears to be a sufficient sec- The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. neglected, and now that it is thoroughly out ond. TOOMEY). Are there any other Senators of hand we apply too late the remedies which The yeas and nays were ordered. in the Chamber desiring to vote? then might have effected a cure. There is The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under The result was announced—yeas 70, nothing new in the story. It is as old as the the previous order, all postcloture time nays 27, as follows: sibylline books. It falls into that long, dis- has expired. -

B O X S C O R E a Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS Was Founded in 1994 by A

B O X S C O R E A Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS was founded in 1994 by A. J. Quigley Jr. (1943-1997) and Harley Sheets for the purpose of documenting and preserving the history of Indiana High School Basketball IHSBHS Officers Publication & Membership Notes President Roger Robison Frankfort 1954 Boxscore is published by the Indiana High School Basketball Vice Pres Cliff Johnson Western 1954 Historical Society (IHSBHS). This publication is not copyrighted and may be reproduced in part or in full for circulation anywhere Webmaster Kermit Paddack Sheridan 2002 Indiana high school basketball is enjoyed. Credit given for any Treasurer Rocky Kenworthy Cascade 1974 information taken from Boxscore would be appreciated. Editorial Staff IHSBHS is a non-profit organization. No salaries are paid to Editor Cliff Johnson Western 1954 anyone. All time spent on behalf of IHSBHS or in producing Boxscore is freely donated by individual members. Syntax Edits Tim Puet Valley, PA 1969 Dues are $10 per year. They run from Jan. 1 – Dec. 31 and Content Edits Harley Sheets Lebanon 1954 include four newsletters. Lifetime memberships are no longer Rocky Kenworthy Cascade 1974 offered, but those currently in effect continue to be honored. Tech Advisor Juanita Johnson Fillmore, CA 1966 Send dues, address changes, and membership inquiries to Board Members IHSBHS, c/o Rocky Kenworthy, 710 E. 800 S., Clayton, IN 46118. E-mail: [email protected] John Ockomon, Harley Sheets, Leigh Evans, Cliff Johnson, Tim All proposed articles & stories should be directed to Puet, Roger Robison, Jeff Luzadder, Rocky Kenworthy, Doug Cliff Johnson: [email protected] or 16828 Fairburn Bradley, Curtis Tomak, Kermit Paddack, Hugh Schaefer. -

Portico: Winter 2013

The Magazine of the University of Indianapolis Winter 2013 What’s your vision? Student Kaitlyn Braunig is poised to share her ideas at a Vision 2030 conversation in November. She was among the many students, alumni, and others who took part in one of the strategic planning exercises. Pages 4–7. WWW.UINDY.EDU 1 Portico Table of Contents 4 8 18 21 President’s forum Scholarly pursuits Work ethic survives ‘Who Do You When Rob Manuel arrived Securing research grants, surgery, heartbreak Think You Are?’ in July, he resolved not to presenting at international UIndy junior Daniel Daudu In a bid to help the campus impose his own vision, but conferences, and publishing of Nigeria is glad to be back community think critically rather to listen to what the articles are all in a day’s on the basketball court, about their identities, UIndy UIndy community had to work for our faculty. applying the work ethic he and Ancestry.com have say. What do you think we Here’s a small sample learned so well from the formed a partnership that is might be in 18 years or so? of their activities. example of his parents. a first in higher education. 5 16 20 22 Strategic planning Something to Let the games begin UM news service process under way shoot for to teach kids shadows student Higher education is in a Gus Chikamba ’03 and his A creative new classroom & president state of flux, and universities wife, Madeline, are serious management system built on The United Methodist News must be prepared to face the about bringing basketball to role-playing is a hit with the Service is shadowing two changes ahead. -

B O X S C O R E a Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS Was Founded in 1994 by A

B O X S C O R E A Publication of the Indiana High School Basketball Historical Society IHSBHS was founded in 1994 by A. J. Quigley Jr. (1943-1997) and Harley Sheets for the purpose of documenting and preserving the history of Indiana High School Basketball IHSBHS Officers Publication & Membership Notes President Roger Robison Frankfort 1954 Boxscore is published by the Indiana High School Basketball Vice Pres Cliff Johnson Western 1954 Historical Society (IHSBHS). This publication is not copyrighted and may be reproduced in part or in full for circulation anywhere Webmaster Kermit Paddack Sheridan 2002 Indiana high school basketball is enjoyed. Credit given for any Treasurer Rocky Kenworthy Cascade 1974 information taken from Boxscore would be appreciated. Editorial Staff IHSBHS is a non-profit organization. No salaries are paid to Editor Cliff Johnson Western 1954 anyone. All time spent on behalf of IHSBHS or in producing Boxscore is freely donated by individual members. Syntax Edits Tim Puet Valley, PA 1969 Dues are $10 per year. They run from Jan. 1 – Dec. 31 and Content Edits Harley Sheets Lebanon 1954 include four newsletters. Lifetime memberships are no longer Rocky Kenworthy Cascade 1974 offered, but those currently in effect continue to be honored. Tech Advisor Juanita Johnson Fillmore, CA 1966 Send dues, address changes, and membership inquiries to Board Members IHSBHS, c/o Rocky Kenworthy, 710 E. 800 S., Clayton, IN 46118. E-mail: [email protected] John Ockomon, Harley Sheets, Leigh Evans, Cliff Johnson, Tim All proposed articles & stories should be directed to Puet, Roger Robison, Jeff Luzadder, Rocky Kenworthy, Doug Cliff Johnson: [email protected] or 16828 Fairburn Bradley, Curtis Tomak, Kermit Paddack, Hugh Schaefer. -

Oscar to Lebron

The Right Man For The Job: Why Oscar Robertson Was the Ideal NBPA President Tom Primosch Haverford College Department of History Advisor: Professor Linda Gerstein First Reader: Professor Linda Gerstein Second Reader: Professor Bethel Saler May 2021 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................3 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................4 Part One: Robertson’s Experiences Growing Up Early Years...........................................................................................................................8 Crispus Attucks and The Klan.............................................................................................9 Robertson’s High School Stardom.....................................................................................14 Mayor Clark’s Decision.....................................................................................................15 Part Two: Robertson’s College Days Branch McCracken’s Insult................................................................................................17 Robertson’s NCAA Tenure..................................................................................................22 The Territorial Draft..........................................................................................................24 Part Three: The NBA’s History of Racism -

Portico: Spring 2012

The Magazine of the University of Indianapolis Spring 2012 Helping to shape the vision An interim director has been named for the nascent Institute for Civic Leadership & Mayoral Archives. Also: UIndy’s Super Bowl role; celebrating Reflector & WICR milestones. WWW.UINDY.EDU 1 Portico Table of Contents 4 8 16 20 President’s forum Scholarly pursuits Interim director You’re listening to Dr. Beverley Pitts, the Faculty shine professionally, eager to explore ‘the Diamond’ eighth president of the as always. The Movement institute’s potential But WICR’s anniversary is University of Indianapolis, Science Lab grows to The Institute for Civic golden, as the station marks says goodbye on the eve become one of the state’s Leadership & Mayoral 50 years of broadcasting. of her retirement. best. The School of Business Archives has a new interim Having started with 10 and Department of Art director who’s excited about watts of power, the station 5 & Design get stamps of what the venture will offer. has grown considerably in approval from accrediting that time. (See also “Happy We’ve come a agencies. And much more. anniversaries,” page 3.) long way 18 A brief overview of what’s 90 years reflecting been accomplished during 14 University life 22 President Pitts’s tenure. Visiting speakers This year, on the heels Superlative challenge & inspire of earning national Super Bowl week on campus 6 A Nobel Peace Prize laureate, recognition, the Reflector was one of superlatives. The ‘Moving to the next a pair of statesmen, a civil is celebrating nine decades Giants loved practicing at level of excellence’ rights leader, and a “war of covering campus news UIndy. -

2018-03-18 Edition

TODAy’s WeaTHER SUNDAY, MARCH 18, 2018 Today: Mostly sunny. Tonight: Partly cloudy. SHERIDAN | NOBLESVIllE | CICERO | ARCADIA IKE TLANTA ESTFIELD ARMEL ISHERS NEWS GATHERING L & A | W | C | F PARTNER FOllOW US! HIGH: 55 LOW: 35 Way to go, County clerks keep skills sharp Grand Chuck! When we are in From the Heart Tampa, I often go out to the golf course and watch Chuck chip and putt and drive and all those golf things he does. I sometimes attempt to entertain him by doing a bit of the same. JANET HART LEONARD Once in a while I do enough to get a high five from him or even, on occasion, I get to do a fist pump. I actually have two official golf shirts. At least I look the part of a golfer. He knew when he married me, while I loved sports, I had never voluntarily par- ticipated in them. It was a few days ago when we were visiting my daughter, Emily, and her fam- ily in Tampa, I was showing Leah a few yoga moves. See Grand . Page 3 World War I exhibit opens next month Photo provided One hundred The County Line Last week, clerks and treasurers from all over the state came together in Muncie for the 23rd annual Indiana years ago this spring League of Municipal Clerks and Treasurers (ILMCT) Institute and Academy. It is a week-long conference World War I was of continuing education with classes designed to equip clerks and treasurers with up to date and relevant raging, and 116,516 information pertaining to municipal accounting and administration. -

William B. Palmer Collection, 1951–1990

Collection # P 0206 OM 0505 WILLIAM B. PALMER COLLECTION, 1951–1990 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Marilyn Rader and Dorothy A. Nicholson March 2014 revised May 2014 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF Photographs: 9 boxes of photographs, 1 box OVA COLLECTION: photographs, 1 OVA color photograph, 1 OVB photograph Negatives: 1 box 4x5 acetate negatives, 1 box of 120 mm acetate negatives, 6 boxes of 35 mm acetate negatives Manuscript Materials: 2 document cases, 1 OM folder Artifacts: 1 artifact COLLECTION 1951–1990 DATES: PROVENANCE: Heritage Photo Services, Indianapolis, Ind. 2002 Linda J. Kelso, Indianapolis, Ind. 2002 RESTRICTIONS: The negatives and color photograph are in cold storage and researchers must request them a day in advance and may view the negatives with the assistance of Library Staff. COPYRIGHT: The photographs in this collection were taken while William Palmer was an employee of the Indianapolis News. REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indianapolis Star, copyright owner of the Indianapolis News. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2002.0342, 2002.0424 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH William Beckner Palmer (1913–1997) was a staff photographer for the Indianapolis News. His assignments were random; society, sports, fire, accident, or human interest. Palmer had a standing assignment of “pick ups,” that meant he could take photographs of whatever he found of interest to the readers.