Bpa/Lower Valley Transmission Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 Affected Environment

Chapter 3 – Affected Environment Chapter 3 Affected Environment In this Chapter: • Existing natural environment • Existing human environment • Protected resources This chapter describes the existing environment that may be affected by the alternatives. A brief regional description is given here to give the reader a better understanding of the information in this chapter. The project area is in the uppermost reaches of the Columbia River Basin, within the Snake River watershed. It is part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which is the largest remaining block of relatively undeveloped land in the contiguous United States. This ecosystem is centered around Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks and includes the national forests, wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, and other federal, state, tribal, and private lands that surround these parks. The landscape is scenic. Dominant features include mountain ranges over 3,660 m (12,000 feet) high, alpine valleys, rivers, broad flat plateaus, picturesque farmlands, and the special features of the national parks. The region is known for its variety of wildlife, unequaled elsewhere in the continental United States. Species present in large numbers include bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, moose, mule deer, elk, and black bear. Wolverines, grizzly bears, and reintroduced wolves are present as well. This region attracts over 5 million tourists and recreationists per year (Wyoming Department of Commerce, 1995). Visitors and local residents enjoy sightseeing, hiking, backcountry skiing, snowmobiling, camping, backpacking, horseback riding, mountain biking, snowboarding, parasailing, hunting and fishing. Because of the concentration of highly visible wildlife species in the region, wildlife-related recreation is a key element of the region’s economy and character. -

2018 Year End Review and Rescue Report

2018 END-OF-YEAR REVIEW & RESCUE REPORT © CHRIS LEIGH www.tetoncountysar.org TCSAR RESCUE REPORT - 1 FOUNDATION BOARD MEMBERS TCSO SAR ADVISORS AND STAFF DEAR FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS MISSY FALCEY, PRESIDENT CODY LOCKHART, CHIEF ADVISOR NED JANNOTTA, VICE PRESIDENT AJ WHEELER, M.D., MEDICAL ADVISOR Teton County boasts some of the most magnificent and challenging terrain BILL HOGLUND, TREASURER PHIL “FLIP” TUCKER, LOGISTICS ADVISOR in the country and our community members take full advantage of this, JESSE STOVER, SECRETARY ALEX NORTON, PLANNING ADVISOR which is awesome and inspiring. With our extensive backcountry use comes LESLIE MATTSON CHRIS LEIGH, MEMBERSHIP ADVISOR great responsibility for both the backcountry user and those charged with rescuing them. RYAN COOMBS ANTHONY STEVENS, TRAINING ADVISOR CLAY GEITTMANN JESSICA KING, TCSO SAR SUPERVISOR Wyoming State Statute 18-3-609 (a) (iii) states: “Each county sheriff shall be the official responsible for coordination of all search and rescue operations RICH SUGDEN MATT CARR, TCSO SHERIFF-ELECT within his jurisdiction.” How each county sheriff interprets this statute is LIZ BRIMMER up to him/her. As the Teton County sheriff-elect, I bring this up because FOUNDATION STAFF I feel strongly that Teton County leads the country in its interpretation of DAVID LANDES coordination of search and rescue operations. DON WATKINS STEPHANIE THOMAS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SCOTT GUENTHER, GTNP LIAISON AMY GOLIGHTLY, COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Gone are the days of wrangling up a few willing deputies to drag someone CASEY LEWIS, SAR TEAM & DONOR RELATIONS DIRECTOR out of the backcountry. Under the leadership of Sheriff Jim Whalen, Teton JESSICA KING, TCSO SAR SUPERVISOR County has built one of the best possible responses to search and rescue CODY LOCKHART, TCSAR ADVISOR LIAISON incidents in the country. -

Greater Yellowstone Trail

Greater YellowstoneTrail CONCEPT PLAN | 2021 UPDATE The work that provided the basis for this publication was supported by funding under an award with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The author and publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government. Greater Yellowstone Trail CONCEPT PLAN | 2021 UPDATE STAKEHOLDER UPDATE MEETING Warm River and historic West Yellowstone Branch Railroad tunnel ACRONYMS BTNF- Bridger-Teton National Forest CDT- Continental Divide Trail CTNF- Caribou-Targhee National Forest CGNF- Custer-Gallatin National Forest FLAP- Federal Lands Access Program HUD- US Department of Housing & Urban Development IDPR-Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation ITD- Idaho Transportation Department NEPA- National Environmental Policy Act NPS- National Park Service OHV- Off-Highway Vehicle TVTAP- Teton Valley Trails & Pathways USFS- United States Forest Service WYDOT- Wyoming Department of Transportation 4 | CONCEPT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Stakeholder Meeting Update ...................................... 7 Executive Summary ........................................................ 19 Overall Trail Corridor Map ...............................................22 ACTIVE PROJECT STAKEHOLDERS: Introduction ......................................................................25 History & Regional Connections ...............................27 -

Wyoming Plant Species of Concern on Caribou-Targhee National Forest: 2007 Survey Results

WYOMING PLANT SPECIES OF CONCERN ON CARIBOU-TARGHEE NATIONAL FOREST: 2007 Survey Results Teton and Lincoln counties, Wyoming Prepared for Caribou-Targhee National Forest By Michael Mancuso and Bonnie Heidel Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Laramie, WY University of Wyoming Department 3381, 1000 East University Avenue Laramie, WY 82071 FS Agreement No. 06-CS-11041563-097 March 2008 ABSTRACT In 2007, the Caribou-Targhee NF contracted the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) to survey for the sensitive plant species Androsace chamaejasme var. carinata (sweet- flowered rock jasmine) and Astragalus paysonii (Payson’s milkvetch). The one previously known occurrence of Androsace chamaejasme var. carinata on the Caribou-Targhee NF at Taylor Mountain was not relocated, nor was the species found in seven other target areas having potential habitat. Astragalus paysonii was found to be extant and with more plants than previously reported at the Cabin Creek occurrence. It was confirmed to be extirpated at the Station Creek Campground occurrence. During surveys for Androsace , four new occurrences of Lesquerella carinata var. carinata (keeled bladderpod) and one new occurrence of Astragalus shultziorum (Shultz’s milkvetch) were discovered. In addition, the historical Lesquerella multiceps (Wasatch bladderpod) occurrence at Ferry Peak was relocated. These are all plant species of concern in Wyoming. In addition to field survey results, a review of collections at the Rocky Mountain Herbarium (RM) led to several occurrences of Lesquerella carinata var. carinata and Lesquerella paysonii (Payson’s bladderpod) being updated in the WYNDD database . Conservation needs for Androsace chamaejasme var. carinata , Astragalus paysonii , and the three Lesquerella species were identified during the project. -

Grand Teton National Park

GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK • WTO MING * UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIO NAL PARK SERVICE Grand Teton [WYOMING] National Park United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 Rules and Regulations -I-HE PARK regulations are designed for the protection of the natural Contents beauties as well as for the comfort and convenience of visitors. The follow ing synopsis is for the general guidance of visitors, who are requested to assist in the administration of the park by observing them. Copies of the complete rules and regulations promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior Page for the government of the park may be obtained at the office of the super History of the Region 3 intendent and at other points of concentration throughout the park. Geographic Features 7 The destruction, injury, defacement, or disturbance of any buildings, Teton Range 7 signs, equipment, trees, flowers, vegetation, rocks, minerals, animal, bird, Jackson Hole 9 or other life is prohibited. The Work of Glaciers 9 Camps must be kept clean. Rubbish and garbage should be burned. Trails 13 Refuse should be placed in cans provided for this purpose. If no cans are Mountain Climbing 14 provided where camp is made, refuse should be buried. Wildlife 18 Do not throw paper, lunch refuse, or other trash on the roads and trails. Trees and Plants 21 Carry until the same can be burned in camp or placed in receptacle. Naturalist Service 23 Fires shall be lighted only when necessary and when no longer needed Fishing 24 shall be completely extinguished. -

Backpacking-The-Teton-Crest-Trail

The Big Outside Complete Guide to Backpacking the Teton Crest Trail in Grand Teton National Park © 2019 Michael Lanza All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying or other electronic, digital, or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, contact the publisher at the address below. Michael Lanza/The Big Outside 921 W. Resseguie St. Boise, ID 83702 TheBigOutside.com Hiking and backpacking is a personal choice and requires that YOU understand that you are personally responsible for any actions you may take based on the information in this e-guide. Using any information in this e-guide is your own personal responsibility. Hiking and associated trail activities can be dangerous and can result in injury and/or death. Hiking exposes you to risks, especially in the wilderness, including but not limited to: • Weather conditions such as flash floods, wind, rain, snow and lightning; • Hazardous plants or wild animals; • Your own physical condition, or your own acts or omissions; • Conditions of roads, trails, or terrain; • Accidents and injuries occurring while traveling to or from the hiking areas; • The remoteness of the hiking areas, which may delay rescue and medical treatment; • The distance of the hiking areas from emergency medical facilities and law enforcement personnel. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY: TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMISSIBLE PURSUANT TO APPLICABLE LAW, NEITHER MICHAEL LANZA NOR THE BIG OUTSIDE, THEIR AFFILIATES, FAMILY AND FORMER AND CURRENT EMPLOYERS, NOR ANY OTHER PARTY INVOLVED IN CREATING, PRODUCING OR DELIVERING THIS E-GUIDE IS LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, INDIRECT, EXEMPLARY, OR PUNITIVE DAMAGES ARISING OUT OF A USER’S ACCESS TO, OR USE OF THIS E-GUIDE. -

Schedule of Events Group Rides Skills Clinic Targhee Map

FREE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS GROUP RIDES SKILLS CLINIC TARGHEE MAP WYDAHO RENDEZVOUS TETON MOUNTAIN BIKE FESTIVAL - 2018 I 1 EMPOWERING THE COMMUNITY 2 I WYDAHO RENDEZVOUS TETON MOUNTAIN BIKE FESTIVAL - 2018 WELCOME TO THE 9TH ANNUAL TVTAP WYDAHO RENDEZVOUS TETON MOUNTAIN BIKE FESTIVAL s the Executive Director maintenance, bikepacking, sports our community so it will continue to EMPOWERING for Teton Valley Trails and psychology, and some morning yoga. proposer and be here for your next APathways I am honored to One thing we are not changing is our visit. THE welcome you to our 9th Annual outlandish and awesome quick-fire Wydaho Bike Festival. The Festival raffle that will take place each evening All the best, COMMUNITY is a fundraiser for Teton Valley Trails in the courtyard on the grass. For and Pathways and supports our goal those in the know we have a few of continuing to work on maintaining “SOCKS” to throw to the crowd. and developing a great trail network We also want to call out the great and to achieve our mission of a trails work that Grand Targhee Resort and and pathways connected community. Trail Boss, Andy Williams, have done In 2018, we are bringing some to bring world class mountain bike changes (again). A second lift has trails to the area. The quality and been brought into service for riders variety of trails available to riders is looking for more moderate flow truly amazing and makes this an idea trails. New cross-country trails and place for the festival. down-hill trails have also been built. -

YELLOWSTONE-GRAND TETON LOOP E Mile 94.8 P K 3 R a .7 Yellowstone NRY VALLE VALLEY TE PAR

YELLOWSTONE-GRAND TETON LOOP MONTANAMONTANA West Entrance HENRYSHEENRYS LKLK WestWest milemile 109.8109.8 MadisonMadison STATESTAATE PARKPARK mmileile 124124.8.8 mile 94.8 YellowstoneYellowstoone GeyserGeyser BasinsBasins 20 ↑ YellowstoneYellowstone OldOld FaithfulFaithful LakeLake Old Faithful Visitor Education Center mile 140.9140.9 WestWest Thumb IslandIsland ParkPark mile 158158.7.7 milemile 81.781.7 GGrantrant VillagVillagee YELLYELLOWSTONEOWSTONE HARRIMANHARRIMAN Mesa Falls STATESTATE PARKPARK NATINATIONALONAL PARPARKK milemile 75.075.0 ScenicScenic BywayByway RoadRoad cclosedlosed in winter:winter: WWestest EEntrancentrance to RRoadoad clclosedosed iinn wiwinternter Hwy 20 alternate SSouthouth Entrance route, open in winter (mid Nov-late April) ↑ UpperUpper ● milemile 61.561.5 Mesa FallsFalls SouthSouth EntranceEntrance milemile 180.4180.44 287287 AshtonAshton IDAHO ↑ milemile 47.047.0 G ↑ 20 MIN 32 JacksonJackson O LakeLake Y CColterolter BaBayy WYOMING W TetonTeton GRANDGRAND TETONTETON Jackson Lake Lodge ↑ 3333 to Rexburg/RigbyRexburg/Rigby SSceniccenic TetoniaTetoonia NATIONALNATIONAL PARKPARK 2626 to IIdahodaho FallsFalls MoranMorana BBywayyway GrandGrand milemim le 207.6207.6 JennyJenny TargheeTarghee GreaterGreaterr Yellowstone GeotourismGeotourism CenterCenter LakeLake DriggsDriggs TETTETONON milemile 7.67.6 3333 VALLEVALLEYY ↑ CraigCraig Thomas DiscoveryDiscovery MooseMoose andand VisitorVisitor CenterCeC nter beginbegin milemile 0.0 VictorVictor Teton ↑ VVillageillage 2626 3311 .6 to RirieRirie 119191 NATIONAL 33/22 ELK -

Teton Pass History Trail Walk Through

Teton Pass History Trail IPhone App: Grand Teton National Park & Jackson Hole – Local history – Tours Group walking through fall foliage. Karen Reinhart. History Trail (28).jpg. Overview of the Trail Take a half-day hike along the History Trail and experience the colorful stories of people who traveled the Old Wagon Road beginning in the 1880s, and later, the Old Pass Road which was built in 1913. The Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum and the Bridger-Teton National Forest invite you to explore a piece of Jackson Hole’s history while hiking an easily accessible trail. Only about a twenty- minute drive from Jackson, Wyoming or from Victor, Idaho, the four- mile History Trail begins at the top of Teton Pass and winds eastward down the mountain ending at Trail Creek Trailhead near the town of Wilson. Early season snow may begin to accumulate in the Teton Pass area as early as mid-October, and may linger into June. So, if you want to see relics of days gone by that are visible along the trail, plan to hike during the summer. It is a non-motorized hiking trail that is open to horse or foot traffic only. While dogs are allowed on the trail, carry a leash and be respectful of others. Be alert to the possibility of moose and bears in the area. 1 We recommend beginning the History Trail hike at the top of Teton Pass and hiking down. Ambitious hikers may also experience the trail from the bottom up or may wish to combine the History Trail with the Old Pass Road for loop options. -

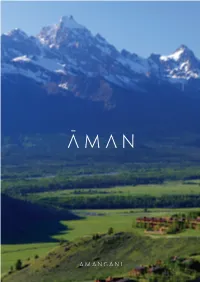

Amangani Factsheet 2021.Pdf

Situated close to some of the USA’s finest ski slopes, as well as Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, Amangani (peaceful home) is an all-season resort overlooking the beautiful valley of Jackson Hole. Perched on the crest of East Gros Ventre Butte, the property affords magnificent views of the Grand Tetons and Snake River Valley. Evoking the atmosphere of the American West, Amangani presents 40 Suites, four free-standing Homes, a spa, an outdoor heated pool with Teton views, and a ski lounge. Location Getting There • Perched on East Gros Ventre Butte • 20-minute drive from Jackson Hole Airport • 2,135m (7,000ft) above sea level • Major airlines and commuter services provide • At the southern end of Jackson Hole across regular access to Jackson via Denver, Salt the valley from Teton Pass Lake City, Charlotte, Seattle, San Francisco, Phoenix, • Magnificent views of the Grand Tetons and Chicago, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Minneapolis and the Snake River Range Los Angeles • 10-minute drive from the town of Jackson • Other airports nearby include Idaho Falls • 20-minute drive from Jackson Hole Regional Airport and Salt Lake City Mountain Resort • Private flights are operated by Jackson Hole Aviation • Amangani Ski Lounge situated in Teton Village • Customised private aviation upon request just below Bridger Gondola Complimentary Inclusions • Custom itinerary planning services • Complimentary ski shuttle to Jackson Hole Mountain resort and access to Ski Lounge in winter • Full use of Fitness Centre • Complimentary Valet Parking Accommodation Amangani’s 40 suites and four Homes all have king-size beds, fireplaces and terraces or balconies with panoramic mountain views. -

Wort Hotel National Register Form Size

NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TEMPLATE RECEIVED 2280 File: NRNOM.FRM (Volume 2/January 1992) NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name: Wort Hotel other names/site number: 2. Location street & number: 50 North Glenwood Street, P.O. Box 69 not for piiblication: N/A city or town: Jackson vicinity: N/A state: Wyoming code: WY county: Teton code: 039 zip code: 83001 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property V meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Teton-West Yellowstone Winter Recreation Economy Report

Teton-West Yellowstone Region Backcountry Winter Recreation Economic Impact Analysis Photo: Tom Turiano Full Report Mark Newcomb November, 2013 1 Abstract This report presents the results of a study that analyzed the annual economic contribution of winter backcountry recreation in Grand Teton National Park, parts of the Bridger-Teton and Caribou-Targhee National Forests, and areas around West Yellowstone in Gallatin Na- tional Forest and Yellowstone National Park. The economic activity impacts communities in Teton County, Wyoming; Teton, Bonneville, Fremont and Madison Counties, Idaho; and West Yellowstone, Montana. We define backcountry recreation to include backcountry skiing and snowboarding (aka AT); cross-country and nordic track skiing; snowshoeing; walking/jogging on groomed backcountry trails; and over-snow biking. The population in- cludes residents of the communities in the region who participated in one or more of those activities as well as nonresidents who participated in one or more of those activities during the course of their visit. We gathered data via surveys administered to a random sample of residents and nonresidents over the course of the 2012/2013 winter season. We estimated the population by aggregating Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement data, National Vis- itor Use Monitoring Data, Grand Teton National Park trail counts and concessionaire use data. We find the total annual direct economic contribution of these activities in the re- gion to be $22,564,461. We estimate the annual direct economic impact by nonresidents who participate in these activities while visiting the region to be $12,073,815. We esti- mate the annual economic contribution of residents to be $6,473,919.